Полная версия:

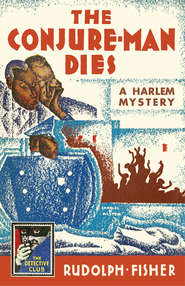

The Conjure-Man Dies: A Harlem Mystery

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of Collins Crime Club reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

Copyright

Collins Crime Club

an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by Covici-Friede, New York 1932

‘John Archer’s Nose’ first published in The Metropolitan by Meeks Publishing Co. 1935 Introduction first published by Arno Press Inc. 1971

First edition cover art by Charles H. Alston 1932

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008216450

Ebook Edition © February 2017 ISBN: 9780008216467

Version: 2016-11-18

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Chapter XX

Chapter XXI

Chapter XXII

Chapter XXIII

Chapter XXIV

John Archer’s Nose

The Detective Story Club

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

THE CONJURE-MAN DIES is, first and foremost, highly readable, wholly entertaining.

This should go without saying, since the book is a mystery novel of merit, and the sole function of any mystery story is to entertain. Of all types of fiction, it is probably the least pretentious, which is all in its favour at a time when the novel is so often used by authors as sugar coating for indigestible messes of philosophy or polemics calculated to make the reading of fiction a duty rather than a pleasure. Or for self-indulgent exercises in Beautiful Writing by poets manqués which make it neither a duty nor a pleasure.

This is not to deny that the formal mystery story does have its limitations, nor that too many of its practitioners, adopting these limitations as a rule book, tend to turn out a sort of mechanically contrived product, one cheapjack job after another rolling off the production line, each similar to the other beneath its coat of paint.

But it is a fact that a writer of authentic talent can and will create within the genre a novel which, while staying in bounds, offers a good example of that talent. Rudolph Fisher was such a writer, and the one mystery novel he wrote, The Conjure-Man Dies, originally published in 1932, offers striking evidence of it, especially when viewed in the light of its times. Its success on publication was great enough to carry it into production as a play by the Federal Theater Project in 1936. Its rediscovery, and appearance in this edition, are no more than proper tributes to both its readability and its merits as a record of its period.

Fisher himself was an extraordinary man. A Negro, born on 9 May 1897 in Washington, D.C., he graduated from Brown University with honours and went on to become a distinguished doctor of medicine, specializing in Roentgenology. At the height of his medical career, he turned to writing as an avocation and was soon being published by such magazines as Atlantic Monthly, Crisis, McClures, American Mercury and Story. A novel, The Walls of Jericho, published in 1928, received high critical praise, and when one adds the success of The Conjure-Man Dies to the list of Fisher’s literary achievements, it is plain that he was at least as talented in writing as he was in the practice of medicine. He died, however, on 26 December 1934, tragically young, and with a brilliantly promising career in letters unfulfilled.

His authorship of The Conjure-Man Dies gave Fisher a lonely distinction. Since the 1860s, when Metta Victor in America and Wilkie Collins in England produced the first formal mystery novels, there had been no Negro writer who utilized this technique as a means of literary expression until Fisher came along. After his death there was again a hiatus until the 1960s, when Chester Himes appeared on the scene with his detective stories of Harlem. The time now ripe for it, Himes, an enormously talented writer himself, came to achieve a prestige and financial success from his mystery stories which Fisher could never have conceived.

What adds a special dimension to Fisher’s novel from the present reader’s point of view is the date of its publication, 1932. The Negro experience that year was still basically unchanged from the era of the Reconstruction. The vaunted Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s had not gone below the surface; excellent as some of the literature emerging from it was, there was a strong smell of the dilettante about the movement, largely emanating from the whites who were part of it. And the Great Depression had stopped even the meagre economic life blood that was left in black communities from flowing. If life everywhere was hard, life in Harlem came down to a desperate day by day struggle for mere survival in a world where the most minimal public works and inadequate welfare payments were only glimmerings on the Rooseveltian horizon, and where the word ‘militant’ was the exclusive property of white-dominated radical organizations.

Under these life and death conditions, the Negro role, as prescribed by the white world, remained consistent. It was a role, familiar as ever, presented to the black by, among other things, the mystery stories of Octavus Roy Cohen in The Saturday Evening Post where the antics of the comically uppity Florian Slappey and his dull-witted, head-scratching cohorts illustrated it so vividly, and by mystery movies where the trusty but terrified and goggle-eyed black servant could perform it larger than life on the screen.

On the other hand, the Negro could take what comfort he might from the solicitous white intellectual and dilettante who, heading in the opposite directon from the arrant racist, sentimentalized the black, romanticized his bitter life style into something delightfully exciting, and, in effect, patted him on the head as one would a pet spaniel. It was ironic and inevitable that neither the racist nor the sentimentalist knew how nicely they were cooperating in the destruction of a people’s identity and individuality by barring the way to the honest exploration and discovery of them. This, of course, is the function of the stereotype, and it matters very little whether the stereotype is that of vicious hound or pet poodle.

The mystery novel of that day, where it dealt with the Negro at all, played both angles. The Negro was either servitor or hardboiled crap shooter, take it or leave it. Hardly surprising when one considers that, first, the mystery novel is popular fiction, and popular fiction always tends to cater to popular prejudices, and, second, that the genre itself had, by and large, used as its subjects the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant middle and upper classes, always acknowledging their superiority to the non-WASP world without question.

The classical mysteries written under these conditions were essentially puzzles where the reader was invited to unearth the murderer before the author did so. Their structures were as rigid as those of a Japanese no play, their characters one-dimensional, their styles generally florid, representative of the snob’s idea of Good Writing. A rereading of S. S. Van Dine, most successful mystery writer of that time, will be enlightening to anyone questioning what might seem excessively harsh judgments in the foregoing.

Luckily, in 1930, there crept into this WASP paradise of genteel murder a serpent named Dashiell Hammett. With a background as Pinkerton investigator and pulp writer, with a superb talent for fiction and a highly-developed social conscience, he plucked the apple right out of the tree that year with his his publication of The Maltese Falcon. Suddenly, murder in the mystery novel showed some of the forms it had already demonstrated in such outstanding pulp magazines as Black Mask and Flynn’s. Suddenly it was booted right out of the vicar’s garden and into the gutter, a much more likely setting for it. There was a hard-edged realism to Hammett’s characters and events, a comprehension of the meanness and viciousness of the urban world they inhabited. And his prose, clipped, economical, earthy, broke completely with the sort of overblown style favoured by S. S. Van Dine and his confreres.

It is highly probable that Rudolph Fisher, intrigued by the idea of presenting Harlem, from top to bottom, in a mystery novel that could reach a larger audience than a straight novel, devoted himself to some serious study of what made the books of both Hammett and S. S. Van Dine tick, since both their approaches are clearly evident in The Conjure-Man Dies. Fisher’s extremely complex plotting and his occasionally too-pedantic writing of descriptive and expository passages is in the classical mode. But the characters, their broad range of background, and the handling of dialogue are wholly of Hammett’s realistic school.

Overall, it is clear that Fisher’s own sympathies and interests lie with Hammett, much as he deferred to traditional techniques. Stylistically, if one judges by the descriptive and expository writing in his novel, The Walls of Jericho, it is possible that he was not so much deferring to what he thought the mystery reader demanded as reflecting a background of pre-World War I reading. Every writer is strongly influenced by the reading he most enjoyed in his teens. It is the exceptional writer who, like Fisher, can dispense with its influence even in part.

In either case, there is no question that it is Fisher’s adherence to the new realism which, as in Hammett’s works, invests The Conjure-Man Dies with the qualities of a social document recording a time and a place without seeming to. One is drawn through the book by its story, but emerges at last with much more than that story in mind.

In the end, of course, it is the book itself that must speak for its author. And what one can best do in introducing a book so happily rediscovered after decades of obscurity is only to mark its place in history, and then step aside.

STANLEY ELLIN

New York, 1971

CHAPTER I

ENCOUNTERING the bright-lighted gaiety of Harlem’s Seventh Avenue, the frigid midwinter night seemed to relent a little. She had given Battery Park a chill stare and she would undoubtedly freeze the Bronx. But here in this mid-realm of rhythm and laughter she seemed to grow warmer and friendlier, observing, perhaps, that those who dwelt here were mysteriously dark like herself.

Of this favour the Avenue promptly took advantage. Sidewalks barren throughout the cold white day now sprouted life like fields in spring. Along swung boys in camels’ hair beside girls in bunny and muskrat; broad, flat heels clacked, high narrow ones clicked, reluctantly leaving the disgorging theatres or eagerly seeking the voracious dance halls. There was loud jest and louder laughter and the frequent uplifting of merry voices in the moment’s most popular song:

‘I’ll be glad when you’re dead, you rascal you,

I’ll be glad when you’re dead, you rascal you.

What is it that you’ve got

Makes my wife think you so hot?

Oh you dog—I’ll be glad when you’re gone!’

But all of black Harlem was not thus gay and bright. Any number of dark, chill, silent side streets declined the relenting night’s favour. 130th Street, for example, east of Lenox Avenue, was at this moment cold, still, and narrowly forbidding; one glanced down this block and was glad one’s destination lay elsewhere. Its concentrated gloom was only intensified by an occasional spangle of electric light, splashed ineffectually against the blackness, or by the unearthly pallor of the sky, into which a wall of dwellings rose to hide the moon.

Among the houses in this looming row, one reared a little taller and gaunter than its fellows, so that the others appeared to shrink from it and huddle together in the shadow on either side. The basement of this house was quite black; its first floor, high above the sidewalk and approached by a long greystone stoop, was only dimly lighted; its second floor was lighted more dimly still, while the third, which was the top, was vacantly dark again like the basement. About the place hovered an oppressive silence, as if those who entered here were warned beforehand not to speak above a whisper. There was, like a footnote, in one of the two first-floor windows to the left of the entrance a black-on-white sign reading:

SAMUEL CROUCH, UNDERTAKER.

On the narrow panel to the right of the doorway the silver letters of another sign obscurely glittered on an onyx background:

N. FRIMBO, PSYCHIST.

Between the two signs receded the high, narrow vestibule, terminating in a pair of tall glass-panelled doors. Glass curtains, tightly stretched in vertical folds, dimmed the already too-subdued illumination beyond.

It was about an hour before midnight that one of the doors rattled and flew open, revealing the bareheaded, short, round figure of a young man who manifestly was profoundly agitated and in a great hurry. Without closing the door behind him, he rushed down the stairs, sped straight across the street, and in a moment was frantically pushing the bell of the dwelling directly opposite. A tall, slender, light-skinned man of obviously habitual composure answered the excited summons.

‘Is—is you him?’ stammered the agitated one, pointing to a sign labelled ‘John Archer, M.D.’

‘Yes—I’m Dr Archer.’

‘Well, arch on over here, will you, doc?’ urged the caller. ‘Sump’m done happened to Frimbo.’

‘Frimbo? The fortune teller?’

‘Step on it, will you, doc?’

Shortly, the physician, bag in hand, was hurrying up the greystone stoop behind his guide. They passed through the still open door into a hallway and mounted a flight of thickly carpeted stairs.

At the head of the staircase a tall, lank, angular figure awaited them. To this person the short, round, black, and by now quite breathless guide panted, ‘I got one, boy! This here’s the doc from ’cross the street. Come on, doc. Right in here.’

Dr Archer, in passing, had an impression of a young man as long and lean as himself, of a similarly light complexion except for a profusion of dark brown freckles, and of a curiously scowling countenance that glowered from either ill humour or apprehension. The doctor rounded the banister head and strode behind his pilot toward the front of the house along the upper hallway, midway of which, still following the excited short one, he turned and swung into a room that opened into the hall at that point. The tall fellow brought up the rear.

Within the room the physician stopped, looking about in surprise. The chamber was almost entirely in darkness. The walls appeared to be hung from ceiling to floor with black velvet drapes. Even the ceiling was covered, the heavy folds of cloth converging from the four corners to gather at a central point above, from which dropped a chain suspending the single strange source of light, a device which hung low over a chair behind a large desk-like table, yet left these things and indeed most of the room unlighted. This was because, instead of shedding its radiance downward and outward as would an ordinary shaded droplight, this mechanism focused a horizontal beam upon a second chair on the opposite side of the table. Clearly the person who used the chair beneath the odd spotlight could remain in relative darkness while the occupant of the other chair was brightly illuminated.

‘There he is—jes’ like Jinx found him.’

And now in the dark chair beneath the odd lamp the doctor made out a huddled, shadowy form. Quickly he stepped forward.

‘Is this the only light?’

‘Only one I’ve seen.’

Dr Archer procured a flashlight from his bag and swept its faint beam over the walls and ceiling. Finding no sign of another lighting fixture, he directed the instrument in his hand toward the figure in the chair and saw a bare black head inclined limply sidewise, a flaccid countenance with open mouth and fixed eyes staring from under drooping lids.

‘Can’t do much in here. Anybody up front?’

‘Yes, suh. Two ladies.’

‘Have to get him outside. Let’s see. I know. Downstairs. Down in Crouch’s. There’s a sofa. You men take hold and get him down there. This way.’

There was some hesitancy. ‘Mean us, doc?’

‘Of course. Hurry. He doesn’t look so hot now.’

‘I ain’t none too warm, myself,’ murmured the short one. But he and his friend obeyed, carrying out their task with a dispatch born of distaste. Down the stairs they followed Dr Archer, and into the undertaker’s dimly lighted front room.

‘Oh, Crouch!’ called the doctor. ‘Mr Crouch!’

‘That “mister” ought to get him.’

But there was no answer. ‘Guess he’s out. That’s right—put him on the sofa. Push that other switch by the door. Good.’

Dr Archer inspected the supine figure as he reached into his bag. ‘Not so good,’ he commented. Beneath his black satin robe the patient wore ordinary clothing—trousers, vest, shirt, collar and tie. Deftly the physician bared the chest; with one hand he palpated the heart area while with the other he adjusted the ear-pieces of his stethoscope. He bent over, placed the bell of his instrument on the motionless dark chest, and listened a long time. He removed the instrument, disconnected first one, then the other, rubber tube at their junction with the bell, blew vigorously through them in turn, replaced them, and repeated the operation of listening. At last he stood erect.

‘Not a twitch,’ he said.

‘Long gone, huh?’

‘Not so long. Still warm. But gone.’

The short young man looked at his scowling freckled companion.

‘What’d I tell you?’ he whispered. ‘Was I right or wasn’t I?’

The tall one did not answer but watched the doctor. The doctor put aside his stethoscope and inspected the patient’s head more closely, the parted lips and half-open eyes. He extended a hand and with his extremely long fingers gently palpated the scalp. ‘Hello,’ he said. He turned the far side of the head toward him and looked first at that side, then at his fingers.

‘Wh-what?’

‘Blood in his hair,’ announced the physician. He procured a gauze dressing from his bag, wiped his moist fingers, thoroughly sponged and reinspected the wound. Abruptly he turned to the two men, whom until now he had treated quite impersonally. Still imperturbably, but incisively, in the manner of lancing an abscess, he asked, ‘Who are you two gentlemen?’

‘Why—uh—this here’s Jinx Jenkins, doc. He’s my buddy, see? Him and me—’

‘And you—if I don’t presume?’

‘Me? I’m Bubber Brown—’

‘Well, how did this happen, Mr Brown?’

‘’Deed I don’ know, doc. What you mean—is somebody killed him?’

‘You don’t know?’ Dr Archer regarded the pair curiously a moment, then turned back to examine further. From an instrument case he took a probe and proceeded to explore the wound in the dead man’s scalp. ‘Well—what do you know about it, then?’ he asked, still probing. ‘Who found him?’

‘Jinx,’ answered the one who called himself Bubber. ‘We jes’ come here to get this Frimbo’s advice ’bout a little business project we thought up. Jinx went in to see him. I waited in the waitin’ room. Presently Jinx come bustin’ out pop-eyed and beckoned to me. I went back with him—and there was Frimbo, jes’ like you found him. We didn’t even know he was over the river.’

‘Did he fall against anything and strike his head?’

‘No, suh, doc.’ Jinx became articulate. ‘He didn’t do nothin’ the whole time I was in there. Nothin’ but talk. He tol’ me who I was and what I wanted befo’ I could open my mouth. Well, I said that I knowed that much already and that I come to find out sump’m I didn’t know. Then he went on talkin’, tellin’ me plenty. He knowed his stuff all right. But all of a sudden he stopped talkin’ and mumbled sump’m ’bout not bein’ able to see. Seem like he got scared, and he say, “Frimbo, why don’t you see?” Then he didn’t say no more. He sound’ so funny I got scared myself and jumped up and grabbed that light and turned it on him—and there he was.’

‘M-m.’

Dr Archer, pursuing his examination, now indulged in what appeared to be a characteristic habit: he began to talk as he worked, to talk rather absently and wordily on a matter which at first seemed inapropos.

‘I,’ said he, ‘am an exceedingly curious fellow.’ Deftly, delicately, with half-closed eyes, he was manipulating his probe. ‘Questions are forever popping into my head. For example, which of you two gentlemen, if either, stands responsible for the expenses of medical attention in this unfortunate instance?’

‘Mean who go’n’ pay you?’

‘That,’ smiled the doctor, ‘makes it rather a bald question.’

Bubber grinned understandingly.

‘Well here’s one with hair on it, doc,’ he said. ‘Who got the medical attention?’

‘M-m,’ murmured the doctor. ‘I was afraid of that. Not,’ he added, ‘that I am moved by mercenary motives. Oh, not at all. But if I am not to be paid in the usual way, in coin of the realm, then of course I must derive my compensation in some other form of satisfaction. Which, after all, is the end of all our getting and spending, is it not?’

‘Oh, sho’,’ agreed Bubber.

‘Now this case’—the doctor dropped the gauze dressing into his bag—‘even robbed of its material promise, still bids well to feed my native curiosity—if not my cellular protoplasm. You follow me, of course?’

‘With my tongue hangin’ out,’ said Bubber.

But that part of his mind which was directing this discourse did not give rise to the puzzled expression on the physician’s lean, light-skinned countenance as he absently moistened another dressing with alcohol, wiped off his fingers and his probe, and stood up again.