Полная версия:

Where Bluebells Chime

ELIZABETH ELGIN

Where Bluebells Chime

Dedication

To

my husband George

and to

my daughters Jane and Gillian.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

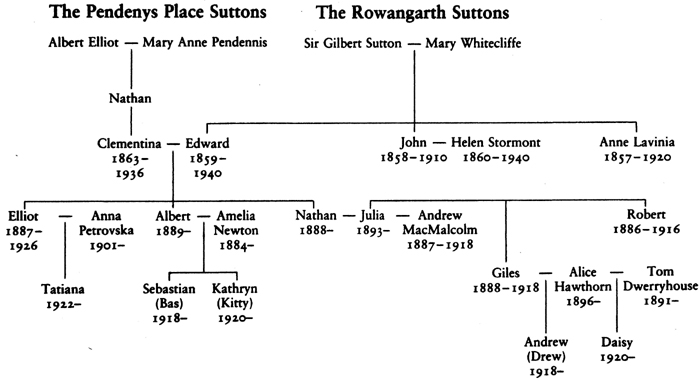

Family Tree

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

About the Author

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Family Tree

1

June 1940

She saw Keth’s letter when the alarm jangled her awake at half-past seven and reached for it, sighing contentment, turning the envelope over to read ‘Open on 20 June’ written across the flap. It must have arrived yesterday, or the day before and Mam had hidden it away then tiptoed into her room last night to prop it against the clock.

She gazed at the colourful American stamp and the air-mail sticker so she might stretch out the seconds before opening it, then frowned to read the postmark. Washington DC instead of Lexington as it almost always was. Why Washington? Quickly, she slit open the envelope.

My darling,

Happy birthday. Close your eyes and know I am thinking of you and wanting you and needing to touch and hold you.

I miss you so much. It should not have been like this. A week ago, I sat my last exam and I know I shall get a good degree. Now I should be packing my cases, heading for New York and a passage home, but nothing is simple any longer. The Atlantic is forbidden, now, to people like me, but I will find a way to be with you.

Since France capitulated I have thought of little else but getting home. Please, darling, take care of yourself and try to keep out of harm’s way. The papers here talk about England being invaded but I can’t believe it can happen – not when I am not there to take care of you and Mum.

There must be a way for us to be together and I will find it. I know you want me to stay in Kentucky, but that is not possible when I need you so desperately and love you so much.

Always remember you are mine.

Keth.

She closed her eyes tightly, trying to smile away the tears that threatened because if she were to weep on her birthday then she would weep all year, Mam said.

‘The summer of ’forty I’ll be back,’ Keth promised, when they parted, but he could not, must not come home.

Today she was twenty and next year, when she came of age, was to have been her wedding day – well, not quite on her birthday, it being a Friday and Friday an unlucky day for weddings. That was why she had ringed round the day after; ringed it on every calendar in the house.

June 21 1941. At All Souls’, Holdenby, by the Reverend Nathan Sutton. Keth Purvis to Daisy Julia Dwerryhouse.

She had read the announcement of their wedding so often in her dreamings. Daisy Purvis. Mrs Keth Purvis. She had promised never to write her married name – not before the wedding that was. As unlucky as a Friday marrying, Mam said, so she had never done it. But it hadn’t stopped her saying it secretly and softly. Daisy Julia Purvis. It made a sound like a love song, like nightingales singing, like the sighing hush of silence before two lovers kiss.

The summer of ’forty. It had been her watchword; words to wear like a talisman, to say over and over when she missed him and wanted him unbearably.

Yet now the summer of ’forty had come and there should have been a letter telling her that soon he’d be sailing from New York, and would she be at Southampton – or Tilbury or Liverpool, perhaps – to meet him when he docked?

Sometimes it had been like that, but sometimes in her dreamings Keth had surprised her, had been waiting where Rowangarth Lane branched off into Brattocks Wood and the footpath that ran through the trees to Keeper’s Cottage; standing there in grey flannel trousers and a white shirt, just as he had been two years ago.

The summer of ’thirty-eight, it had been – their daisychain summer – yet now that longed-for summer of ’forty had arrived and Keth was still in Kentucky. It was where, truth known, she wanted him to stay.

Don’t come home, Keth. Stay in America where you’ll be safe.

America wasn’t at war. America was safety and young men living their lives without fear of call-up; young men knowing they could make plans, go to university, get jobs, stay alive. So she didn’t really want that letter saying he was coming home because if he did, They, the faceless ones, would take him. There had been no heady, patriotic rush to volunteer as there was in Dada’s war. This time, They had already put their mark on every fit young man of twenty-one and dubbed them the militia. Conscripts, really. Six weeks in barracks; forty-odd days in which to accept the discipline of life in the armed forces, to march like automatons in foot-blistering boots; learn to salute Authority and acknowledge that henceforth and for the duration of hostilities, each was no more than a surname and a number. Then away to active service, and some of them killed already.

Stay, Keth. She sent her thoughts winging high and far. I’d rather wait four years, if four years it takes, than have you no more than a name on a gravestone in some foreign cemetery.

She heard the creaking of the stairs and laid her lips briefly to the letter in her hand. Then she swung her feet to the floor. Mam was coming to wish her a happy birthday. Daisy forced her lips into a smile …

When Daisy said goodbye to Reuben Pickering that night, he stood at his almshouse door, waiting to wave to her as she reached the corner. She always turned for one last wave and every time she did she wondered if she would see him again. You never knew what might happen in wartime, and besides, Reuben was frail and old; very old. Over ninety, Mam said, though she would never tell how many years over ninety. You didn’t remind people, especially Uncle Reuben, about their age, she admonished when Daisy once asked. So Daisy always tried, now, to treat the retired gamekeeper as if every time she saw him would be the very last and to be especially kind to him, not just for the sake of her conscience, but because she loved him very much.

Reuben was a part of her life, had always been there – a part of Mam’s life, too. A sort of father, really, because Mam had never had one – or not that she remembered. That was why today in her dinner hour, Daisy had stood in a queue outside a sweet shop and when she reached the counter, had chosen humbugs because they were Reuben’s favourite, though she would have to tell him she was sorry there had been no tobacco queue, but that she would try to get him some tomorrow.

Tobacco and cigarettes were even harder to come by now than humbugs. But yesterday she hadn’t looked for queues during her dinner hour. Yesterday she had –

Daisy blinked her eyes as she stepped from the mellow evening sunlight and into the green-cool dimness of Brattocks Wood, breathing in the damp, mossy scent of it to calm herself, because whenever she thought of what she had done yesterday in her dinner hour, her heart started to bump – especially when she realized that before so very much longer she would have to tell her parents about it. She had almost decided it must be tonight, though it would be awful, telling them on her birthday.

Then she salved her conscience almost at once by remembering that Sunday was to be her official birthday, with Aunt Julia calling for Reuben and bringing him to Keeper’s in her car and the two of them staying for a birthday tea. It was good of Aunt Julia, come to think of it, since petrol was rationed now, and no one got half enough.

But yesterday had started badly. She had awakened and thought that this day next year should have been her wedding day and it wouldn’t be, now, because of the bloody awful war. She had known with dreadful certainty it would not. Keth would not be home, now, though she knew she should be glad he was in America and out of harm’s way. There was no way, now, of crossing the Atlantic unless you were a merchant seaman, sailing square-packed in convoys or unless you were in the Air Force and could fly across in a warplane.

Civilians could no longer buy a sailing ticket or a seat on a flying-boat, because all transatlantic liners were troopships, now, and flying-boats had been commandeered by the Air Force and painted in the dull colours of camouflage to be a part of Coastal Command. Besides, the Atlantic was a dangerous place to be, packed with German submarines and battleships sailing where they wanted, doing exactly as they pleased because Britain was still licking its wounds after Dunkirk and could do little to stop them.

An aircraft flew low overhead, crashing into her thoughts. She could not see it through the denseness of the branches above her but she knew it was one of the bombers from the aerodrome at Holdenby Moor. There were two squadrons there now and last night they had flown over Germany again, dropping their bombs – an act of defiance, really, when everything was in such a mess and everyone worrying about the invasion. But when it came people would make a fight of it, though in France they hadn’t been given much of a chance. Hitler’s armies had just marched on and on …

But we had the Channel – the English Channel – and Hitler had to cross it first. And we had a navy, still, to help stop them, so perhaps it would be all right. Maybe the Germans wouldn’t come.

Daisy looked down at her watch. Mam wouldn’t be home from the canteen yet, nor Dada from his meeting. She squinted up at the sun dappling through the trees. Soon, when it reached the cupola of Rowangarth stable block it would start slowly to set. Blackout tonight would be at eleven o’clock and remain until daylight came about five tomorrow morning.

The blackout, Daisy frowned, was the strangest thing about the war, especially in winter when it began at teatime and lasted until long past breakfast time, next day. Last winter had been bleak and cold and very dark, and the blackout had taken a lot of getting used to. Stepping out into it, even from a dimly lit room, was like stepping into sudden blindness. So you stood there, if you had any sense, and gave yourself up the the blackness, eyes blinking until shapes could be picked out against the skyline. Shapes – outlines of buildings, that was, and trees – and especially in towns you stood still until your eyes could make out not only shapes but the white bands painted on gateposts and lampposts and telegraph poles and corners of buildings; unless you wanted a bloody nose or a black eye, of course, from walking into things you couldn’t see. ‘Bumped into a lamppost, did you?’ people would grin, with no sympathy at all for bruises or shattered spectacles.

But there would be virtually no blackout tonight because it was June and would hardly get dark because of that extra, unnatural hour of double summertime. She must remember to think about June evenings when the drear of November was with them.

Drew, her half-brother, had joined the Royal Navy. His last letter had been from signal school where he was learning to read morse. And when he had, he’d be sent to a ship and only heaven knew where he would end up.

Once, Daisy sighed, there had been six of them: herself and Drew and Keth and Tatiana, with Bas and Kitty over from Kentucky each summer and every Christmas. Her Sutton Clan, Aunt Julia called them.

They had been golden summers and sparkling Christmases in that other life, yet now Bas and Kitty could no longer visit, and Keth was staying with them because he had gone to university in America with Bas. And with Drew gone there was only her and Tatty left to remember how it had once been; how very precious.

Tatty was eighteen now, beautiful, and fun to know. She wanted to do war work, but her Grandmother Petrovska, who never ceased to remind anyone who would listen that she was White Russian and a countess, had forbidden it absolutely.

Poor Tatiana. And poor Daisy, who’d better be getting home to Keeper’s Cottage to tell her parents her secret. And when she told them, Mam would burst into floods of tears and Dada would shout and play merry hell so that Mam would have to tell him to watch that temper of his before it got him into trouble. And when Mam said that, Daisy would know that the worst was over and that Mam at least was on her side.

But oh, why had she done it – especially now?

Julia Sutton offered the letter to her mother, smiling indulgently. ‘I’m to thank you, Drew says, for the soap and chocolate, but he says you mustn’t bother now they’re rationed – but read it for yourself …’

‘No, dear.’ Helen Sutton placed a cushion behind her head, then closed her eyes. ‘My glasses are upstairs. Read it to me.’

‘We-e-ll – he says to thank you for the things you sent but you’re not to do it again because they can get quite a lot at the NAAFI in barracks. Soap, razor blades and cigarettes, too.’

‘Oh, I do hope he hasn’t started smoking.’

‘I hope so, too,’ Julia sighed. ‘It’s murder when you haven’t got one.’

Cigarettes were in short supply to civilians. Shops doled them out now five at a time – if you were lucky enough to be there, that was, when a cigarette queue started.

Julia smoked; a habit begun when she was nursing in the last war. She had carried cigarettes in her apron pocket, lighting one, placing it between the lips of a wounded soldier. And then came the day when she too needed them. Cigarettes soothed, filled empty spaces in hollow stomachs, became a habit she could not break.

‘And he says that when they aren’t in the classroom they are cleaning the heads – I think he means the lavatories – and polishing brass and the floors, too. It’s a stupid way to fight a war, Mother, if you want my opinion!’

‘Maybe so.’ Helen Sutton stirred restlessly. Talk of war upset her; talk of Drew being in that war was even worse. ‘But I’d rather he polished floors for ever than went to sea.’

‘He’ll be safer at sea than he’d be if he were flying one of those bombers from Holdenby Moor. Will Stubbs said they lost three last night.’ Such a terrible waste of young lives. ‘Anyway, once Drew has finished his course he’ll get leave, he thinks, before they find a ship to send him to. I suppose things are in a bit of a mess still, after Dunkirk.’

‘I don’t know why they took him if they don’t know what to do with him,’ Helen fretted.

‘They will, in time,’ Julia soothed. ‘We’ve got to sort ourselves out, don’t forget.’ And who could forget Dunkirk?

But her mother was growing old. It had to be faced. Before war came – before another war came – Helen Sutton had looked younger than her years, but now Julia worried about her. She seemed so frail lately; hadn’t eaten properly since Drew left three months ago. It was as if that Sunday last September when they knew they were at war again had turned her world upside down and she was still floundering.

‘He’ll be all right, won’t he, Julia?’

‘He’ll be all right, dearest. I feel it, know it. Drew will come home to us.’

‘Yes, he will. And I’ll write to him, tomorrow – too tired tonight. Do you think you could ring for Mary, ask for my milk?’

‘I’ll get it myself,’ Julia smiled. ‘Mary is, well, busy, these days.’

Lately, Mary Strong was most likely to be found in the grooms’ quarters above the stables. After almost twenty years of courtship, Will Stubbs had at last been pinned down. A day had been set for the wedding, the banns already called once at All Souls’.

‘I tell you, Will, I’ll wait no longer,’ Mary had stormed. ‘I’m the laughing stock of Holdenby, the way I’ve let you blow hot and blow cold. Well, those Nazis are coming and when they do, I want a wedding ring on my finger – is that understood?’

Will had understood. If the Germans did invade, he might as well be married as single. It would matter little. When the Nazis came – and Will had deduced they well might – they’d all be thrown into concentration camps anyway. Best do as Mary ordered and wed her.

‘I never thought she’d get Will Stubbs down the aisle,’ Julia smiled as she closed the door behind her.

Tilda was sleeping in the chair – in Mrs Shaw’s chair – when Julia poked her head round the kitchen door and she jumped, gave a little snort, then blinked her eyes open.

‘Sorry to disturb you – I’ve come for Mother’s milk.’

‘All ready.’ Tilda was instantly awake.

On the kitchen table lay a small silver tray on which stood the pretty china saucer her ladyship was fond of and the glass from which she drank her nightly milk and honey. Beside it was an iron saucepan, a milk jug and honey jar and spoon. Tilda Tewk was nothing if not methodical, now she had taken over Mrs Shaw’s position as Rowangarth’s cook.

‘I’ll just pop a pan on the gas, Miss Julia. Be ready in a tick.’

‘Thanks, Tilda.’ Julia sat down on the chair opposite to wait. ‘I called on Mrs Shaw, today. She seems to have settled in nicely, though she’s sad, she said, that she had to wait for Percy Catchpole to die before she could get an almshouse to retire into.’

‘There’s been a lot of changes, Miss Julia, amongst the old folk. Think it was the war coming that has to answer for it. Seemed as if they just couldn’t face another. But I couldn’t help noticing, ma’am, that there was a letter from Sir Andrew by the late post. How is he then, and when will us see him?’

‘Drew is fine, and looking forward to his first leave,’ Julia smiled. ‘I’ll tell him you asked.’

‘You do that. And tell him when he comes home as Tilda’ll see he’s well looked after. He’ll not be eating overwell, now that he’s a sailor.’ Food rationing or not, young Sir Andrew would have nothing but the best when he came on leave and there’d be his favourite iced buns and cherry scones, just like Mrs Shaw used to make. Tilda Tewk had glacé cherries secreted away for just such an occasion – aye, and more sugar than anyone in this house knew about! The last war had taught her a lot about squirrelling away and this war, when it came, had not caught her napping! ‘Now here’s her ladyship’s glass, though you’d only to ring and I’d have answered.’ There was little to do now at Rowangarth, even though Mary was so taken up with her wedding and Miss Clitherow, the housekeeper, away to Scotland to the funeral of a relative. ‘And when do you expect the Reverend, Miss Julia?’

‘Late, I shouldn’t wonder. A parishioner, you know – the Sacrament.’

‘Ah,’ Tilda nodded. Flixby Farm, it would be. The old man had been badly for months.

‘Go to bed. I’ll wait up,’ Julia offered.

‘Nay, miss, there’s no hurry. Mary’s still out so it’ll be no bother and any road, I promised Miss Clitherow before she went that I’d check the blackout.’

‘Have you heard from her, Tilda?’

‘Only once, to let us know she’d got there – eventually. A terrible journey, by all accounts. Two hours late arriving, and no toilet on the train.’

‘That’s the war for you,’ Julia sighed, wondering if anything would ever be the same again and refusing, stubbornly, even so much as to think about the threat of invasion.

Tom Dwerryhouse sat in the rocker in the darkening kitchen, reluctant to draw the thick blackout curtains, needing to suck on his pipe, sort things out in his mind.

Nothing short of a fiasco, that meeting had been, with no one knowing rightly what to do. The formation of the Local Defence Volunteers it was supposed to be; civilians who were willing to stand and fight if the Germans came. And come they would, Tom frowned, since there seemed nowhere else for them to go except Russia, and they’d signed a pact with Russia not to fight each other.

Strange, when you thought about it – Fascists and Communists, ganging up together. The two didn’t mix, any fool knew that. But happen they’d only agreed the non-aggression pact because each was scared of the other. And long may it remain so. A bit of healthy mistrust was just what Hitler could do with – the need to look over his shoulder at the Russians – wonder if they would stab him in the back.

But Stalin was nowt to do with us. What was more important was getting some kind of order into the Volunteers. There had been all manner of opinions put forward and no one agreeing until in the end the Reverend had suggested he contact the Army in York and ask them to send someone over to talk to the men.

Then the Reverend had been called away to Flixby Farm and that had more or less been that. A right rabble they were – no uniforms, no rifles. Those men who owned shotguns had brought them, but the cowman from Home Farm had arrived with a hay fork over his shoulder, which was all he could muster, and hay forks – shotguns, even – weren’t going to be a lot of use against tanks and trained soldiers. Hitler would pee himself laughing if he knew, and be over on the next tide!

Tom gazed into his tobacco jar, wondering if he could indulge himself with a fill. He had shared his last ounce with Reuben and only the Lord knew when he could get more.

And soon beer would be in short supply, the landlord at the Coach and Horses in Creesby had been heard to prophesy gloomily. On account of sugar being rationed, that was. No option, really, when the breweries had had their sugar cut, an’ all.

But beer was the least of Tom Dwerryhouse’s worries. What really bothered him was all the talk of invasion. People spoke about it in a kind of subdued panic, as if it couldn’t really happen. Not to the British.

But things were bad: the French overrun and British soldiers snatched off Dunkirk beaches reeling with the shock of it. It was all on account of that Maginot Line, Tom considered gravely. Smug, the French had been. No one would ever breach their defences; not this war.

But they hadn’t reckoned with Hitler’s cunning in invading the Low Countries. Never a shot fired in anger, because his armies had just marched round the end of the invincible Maginot Line and had been in Paris before the French could say Jack Robinson. Only Hitler could have thought of pulling a fast one like that and getting away with it. A genius was he, or mad as they come?

Tom reached again for his tobacco. He needed a fill. Things were writhing inside him that only a pipe could soothe. It wasn’t just the invasion and taking care of Alice and Daisy and Polly, if it happened; it was that Local Defence lot in the village. He had left Keeper’s Cottage expecting to join it and be treated with the respect due to an ex-soldier, but all they’d done was witter amongst themselves, tie on their Local Defence Volunteer armbands and agree to meet another night. And there was nothing like an armband for scaring the wits out of a German Panzer Division!