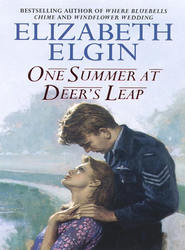

скачать книгу бесплатно

‘And you’re sure you’re all right, Cassie?’

‘Loving every minute of it!’

‘Oh dear. The card’s running out. Love to Jeannie when she comes, and take care of –’

The call ended with a click and I smiled at the receiver by way of a goodbye, then plugged in my machine and screen. I would work until I felt hungry; no stopping for coffee breaks.

I had just decided to write one more page and then I could stop for a sandwich, when Hector growled from the back door, all at once alert.

‘What is it?’ I frowned, but he was gone, barking angrily.

I got up and went to the door. From the direction of the front gate came a furious clamour. A walker, was it, needing to ask directions?

I made for the front gate calling, ‘Stop it, Hector!’ then gasped, ‘Oh, flaming Norah!’

Beside the gate was a red BMW; a few feet back from it stood an angry-faced Piers. On the other side of it, Hector was at his magnificent best when confronting a strange male.

I grabbed hold of his collar then said, ‘Piers! What are you doing here? How did you know …?’

‘Look – just lock that animal up, will you? The blasted thing went for me as I tried to open the gate!’

‘He doesn’t like strange men!’

‘Ha! You could’ve fooled me! It nearly had my hand off!’

‘Don’t be silly!’ Hector continued to snarl, despite my hold on him. Hector, when angry, took a bit of controlling and I decided to put him in the outhouse. ‘Wait there,’ I said snappily, still shocked and not a little dismayed Piers had found me.

‘Why have you come?’ I demanded as I filled the kettle. ‘I mean, I made it pretty clear I didn’t want anyone here. I came to work and anyway, this isn’t my house. I can’t go treating it like it’s a hotel. It wouldn’t be right.’

‘Your father and mother visited – why not me?’

‘Mum and Dad are different.’

I could feel the tension round my mouth and it wasn’t entirely because I was angry. Piers had been determined to find me, probably annoyed because I wasn’t as biddable as I used to be, and wanting to know why.

‘And I’m not? I thought we had something going, Cassandra. It was good between us till you got this writing bug.’ He was doing it again: trying to belittle what I had achieved. ‘Coffee, please. Black, no sugar.’

‘I know!’ I said snappily, turning my back on him because I couldn’t bear to look at the did-you-think-I-wouldn’t-find-you smirk on his face. ‘Who gave you this address?’ I handed him a mug. ‘Did you wheedle it out of Mum?’

‘Not exactly …’

‘Then how?’ I glared, sitting down opposite.

‘I went to Greenleas. There was a postcard of Acton Carey on the mantelpiece.’

‘Oh, clever stuff, Piers! So who gave you directions?’

‘The postman. I asked him where I could find Deer’s Leap. And your mother didn’t tell me. She let it slip, accidentally. “Deer’s Leap is such a lovely house,” she said. “Very old and quaint. Cassie loves it there.” I don’t think she saw me pick up the postcard, by the way.’

‘You’re a sneaky sod!’

I went over to the dresser to sweeten my drink and he was on his feet in a flash, arms round my waist, pulling me close.

‘Stop it, unless you want coffee all over you! This is neither the time nor the place, so don’t get any ideas! You just can’t come barging in, upsetting things,’ I flung when I had the distance of the tabletop between us again. ‘You can’t take no for an answer; always want your own way in everything!’

‘Answer, Cassandra? I don’t recall asking any relevant question.’

‘Not questions,’ I was forced to admit, ‘but you did take it for granted I’d go to London, didn’t you? And you’ve no right to come here, stopping me writing. You know I can’t write if I get upset!’

‘Ah, yes. You’re a creative type. I forgot you must have your own space!’

I almost lost my temper, then; yelled at him to get out. But I took a deep breath and wondered if I should open the outhouse door, let Hector sort him out.

Instead, I said, ‘You can’t stay the night, Piers. It’s not on – not in Beth’s house!’

All at once I disliked him a lot, resented the way he could sit there unruffled and make me want to lose my temper. And I resented the underhand way he’d found me.

‘I mean it!’ I said as evenly as I could. ‘If I’d wanted you here, Piers, I’d have asked you. I came to look after the animals and the house for Jeannie’s sister, and to write.’

‘And I don’t merit just one day of your time, Cassandra?’

His expression hadn’t changed, his hands lay unmoving on the tabletop. All at once I wished him in a bomber, hands tense, his eyes and ears straining, wanting desperately to live the night through. And he’d soon be told to get his hair cut! He never had a hair out of place; Jack Hunter’s fell over one eye and he pushed it aside with his left hand; didn’t know he was doing it.

‘Come and see the garden, or better still walk with me to the top of the paddock, Piers?’

‘Why?’

‘I want to talk to you.’

‘Can’t we talk here?’

‘I’d rather walk.’ I wanted him out of the house.

‘OK. If that’s what it takes.’

He got carefully to his feet, shrugging his jacket straight, indicating the door with an exaggerated, after-you gesture and I thought yet again he should have been an actor. I locked the back door behind me and slipped the key into my pocket. ‘This way,’ I murmured, deliberately walking past the outhouse.

Hector snarled as we passed, and threw himself at the door, and I knew Piers had got the message.

‘Isn’t it beautiful?’ I waved an arm at the distant hills.

‘Very pretty, Cassandra.’ He was leaning, arms folded, against the dry-stone wall now, his boredom turning down the corners of his mouth. ‘So what have you to say to me?’

He didn’t yawn. I expected him to, but he spared me that and I was glad, because I think I’d have hit him if he had.

I drew in a breath, then said, ‘You and I have come to the end of the road, Piers. We aren’t right together. I don’t want to see you any more. It’s over.’

‘What’s over, Cassandra?’

‘Us. You and me. We couldn’t make a go of it.’

‘But I never thought we could! Your heart was never in it, even when we were in bed. To you it was just something else to put in a book – how it’s done, I mean.’

‘And you, Piers, made love to me simply because I was there and available. Another virginal scalp to hang on your belt, was I?’

‘I thought you’d enjoyed it …’

‘I did – at the time.’ I had to be fair. ‘It was afterwards, though, that I didn’t like.’

‘What do you mean – afterwards?’ He was actually scowling.

‘When it was over, Piers. I looked at you and found I didn’t like you. Oh, it was good at the time, but I think that when two people have made love they shouldn’t feel as I did – afterwards.’

‘Cassandra! You’re making it into a big deal! It was an act of sex, for Pete’s sake! You were willing enough. Curious, were you?’

‘Yes, I’ll admit I was and I was quite relieved it went so well. I was afraid I’d make a mess of it. I’d wondered a lot what it would be like, first time. But I think it isn’t any use being in love with a man if you don’t love him too.’

‘There’s a difference?’ He was looking piqued.

‘For me there is. Look, Piers – you and I grew up together. All the girls in the village fancied you. Then you went away to university and when you came back to Rowbeck you singled me out. I was flattered.’

‘I didn’t have a lot of choice. Rowbeck wasn’t exactly heaving with talent!’

‘Point taken!’ Piers was himself again! ‘But I always thought that the first time I slept with a man, he’d be the one, you see. And it seems you aren’t.’

‘Why aren’t I?’

‘I don’t know.’

Oh, but I did. He wasn’t young and vulnerable and fair. And his hair wasn’t always getting in his eyes – he wouldn’t let it! And he wasn’t desperately in love with me either, and sick with fear that each time we parted would be the last.

‘Piers!’ I gasped, because he was staring ahead and not seeing one bit of the beautiful view. ‘I just want us to be friends like when we were kids.’

‘But we aren’t kids. You aren’t all teeth and freckles, Cassandra, and mad at being called Carrots. You’ve grown up quite beautifully, as a matter of fact.’

‘Thanks,’ I said primly. ‘Flattery will get you everywhere – but not today. Sorry, but that’s the way it is. I really must work.’

‘Work? You don’t know the meaning of the word.’

He said it like a grown-up indulging a child and I knew I had made my point at last. I held out my hand.

‘Friends, then?’

‘OK.’ He smiled his rueful smile, then kissed my cheek. ‘My, but you’ve changed, Cassie Johns. Is there another bloke, by the way?’

‘No.’ I shook my head firmly. ‘And you’d best not tell Mum you’ve been. She’d be upset if she thought she’d given my whereabouts away.’

‘So you said she mustn’t let me have your address?’

‘Yes. I didn’t want any interruptions.’

‘I see. Would you mind, Cassandra, if I gave you a word of advice? Don’t take this writing business too seriously?’

‘I won’t,’ I said evenly, amazed he seemed no longer able to annoy me. ‘You’ll want to be on your way, Piers …?’

‘Mm. Thought I might take a look at Lancaster, get a spot of lunch.’

‘I believe it’s a nice place,’ I said as we climbed the stile in the wall. ‘They used to hang witches there.’

‘You haven’t seen it? Come with me – just for old times’ sake – a fond farewell?’

‘Thanks, but no.’ Deliberately I took the path that led to the kissing gate. ‘And thanks for being so understanding – about us, I mean, and me breaking it off.’

He got into his car, then let down the window.

‘There was never anything to break off, Cassandra. Like you said, another scalp …’

I stood for what seemed like a long time after he had driven down the dirt road in a cloud of dust thinking that, as always, he’d had the last word. But I could get along without him. I shrugged, closing the kissing gate behind me.

I let go a small sigh, straightened my shoulders then walked, nose in air, to let Hector out.

All at once, I was desperate for a cheese and pickle sandwich.

Chapter Eight (#ulink_fdf8bf67-ddbe-5397-aae6-cf60214a90a3)

Page two hundred and fifty, and the end of chapter seventeen. I rotated my head, hands in the small of my back. Cassie Johns her own woman again, Firedance ahead of schedule and the mantel clock telling me it was time for tea and a biscuit.

I felt a surge of contentment, a kind of calm after this morning’s storm, waiting patiently for the kettle to boil, gazing arms folded through the window to the hills and the purple haze of heather coming into flower.

I would miss the space, the wideness of the sky, the utter peace of Deer’s Leap when I went home. I had just absently plopped a saccharin into my cup when the phone rang again. I had a vision of Piers calling me on his mobile, telling me he was lost in the wilds of Bowland.

‘Hi, Cas! It’s Jeannie. I’m leaving now. See you tonight, uh?’

‘You’re taking an extra day? But that’s wonderful! What time shall I meet you?’

‘It’s part business, part pleasure, so I’m driving up. I’ll tell you about it when I see you. I’d like to be clear of London before the rush hour starts. Once I’m on the M6 I’ll stop at the first caff for something to eat, so don’t bother cooking.’

‘You’re sure?’

‘Absolutely! I’ll be there before dark. See you!’

‘That was Jeannie,’ I said to Hector, who had heard the rattle of the biscuit tin. ‘She’s coming tonight and there’s not a thing to eat in the house!’

I took a sip of tea, giving a biscuit to Hector. I would go right away to the village in case Jeannie got her foot down on the motorway and decided not to stop. Anyway, I was low on coffee.

Chicken pie, peas, oven chips – I made a mental list – coffee, white wine and a phonecard. Mum would cluck and scold for not waiting until after six, but she’d be pleased to hear from me. I smiled at the red rose that peeped, nodding, through the kitchen window, feeling almost completely happy, wondering if I wasn’t tempting fate, because no one could feel this smug and go unpunished. I looked at the calendar beside the fireplace. Soon, Beth’s lot would be home and I would have to give back Deer’s Leap. Just to think of it wiped the smirk from my face.

‘Want to come to the village?’ I reached for Hector’s lead and he was at the door with a yelp of delight, tail wagging. I would miss Hector too.