скачать книгу бесплатно

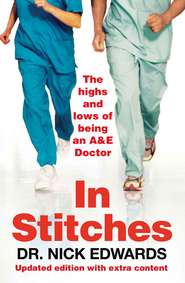

In Stitches

Nick Edwards

The true story of an A&E doctor that became a huge word-of-mouth hit – now revised and updated.

FROM THE PUBLISHER THAT BROUGHT YOU CONFESSIONS OF A GP.

Forget what you have seen on Casualty or Holby City, this is what it is really like to be working in A&E.

Dr Nick Edwards writes with shocking honesty about life as an A&E doctor. He lifts the lid on government targets that led to poor patient care. He reveals the level of alcohol-related injuries that often bring the service to a near standstill. He shows just how bloody hard it is to look after the people who turn up at the hospital door.

But he also shares the funny side – the unusual ‘accidents’ that result in with weird objects inserted in places they really should have ended up – and also the moving, tragic and heartbreaking.

It really is an unforgettable read.

First published in 2007 when The Friday Project was a small independent, In Stitches went on to sell over 15,000 copies in the UK, the majority of which have come in the years since then. It has proved to be a real word-of-mouth hit.

This new edition includes lots of additional material bringing Nick’s story completely up to date including plenty more suprising, alarming, moving and unforgettable moments from behind the A&E curtain.

Dr. Nick Edwards

In Stitches

The Highs and Lows of Life as an A&E Doctor

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain in 2007 by Friday Books

Text © Dr Nick Edwards

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

In Stitches is not authorised or endorsed by the NHS and opinions expressed within this book do not reflect those of the NHS. All situations and characters contained within the book are amalgamations of different scenarios at different hospitals and names and timings have been changed to protect anonymity. The author would like it to be known that he is writing under a pseudonym.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9781905548705

Ebook Edition © MAY 2013 ISBN: 9780007332700

Version: 2018-11-15

To Mrs Edwards: everything I do, you make possible and worthwhile. Thank you so much.

Disclaimer: this book is an attempt to take a humorous look at what it is like to work in a British Accident and Emergency Department. Much of it is tongue in cheek, so do not use it as a guide on how to manage illnesses. Call your GP or, if you can’t be bothered to wait for their receptionist to answer the phone, call an ambulance and come on down to your local A&E department for 3 hours and 59 minutes of fun.

Introduction

It was a fairly standard Saturday at work; generally busy and stressful but interrupted by episodes of upset, excitement and amusement. However, being honest, I quite enjoyed myself. I found pleasure in successfully treating someone’s heart failure and liked being able to mend a patient’s dislocated shoulder. I was amused by a drunk and injured tough-looking biker-type who had got into a fight over a game of chess. And I had a quite fascinating conversation with a man in his late 80s (who came in after a car accident), who insisted on telling me about his current sex life difficulties. Overall, if you have got to work, then working in A&E (Accident and Emergency) is one of the most interesting jobs I could think of and I am glad that it is the job I do.

Admittedly, I got mildly frustrated by the sheer number of patients who were revelling in the British culture of getting as pissed as possible, starting a fight and then coming in to A&E. And yes, I got a little weary of seeing a number of patients who had not read the big red (and quite explicit) sign as they walked in, and who had neither an accident nor an emergency and should have seen an out-of-hours GP (if one had been more readily available). However, overall, I saw a lot of patients who genuinely needed our services and whom we could help, which is the bit of my job that I love.

There was one patient that I took an instant liking to. She was in her mid-80s and had such a fast wit and spark to her personality that she felt like a breath of fresh air as I was treating her. She touched my emotional heartstrings because she reminded me of my Great Aunt.

She came in after having collapsed at home with abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhoea. We were busy and she had had to wait 2 hours to see me. I quickly made the diagnosis of a possible gastro-enteritis (stomach bug), gave her some fluids, took some blood, organised an X-ray and arranged for admission. I wanted to wait for the results, spend more time with her and manage her care accordingly, but in a flash she was whisked away to a care of the elderly ward for me never to see her again. An hour after she arrived on the ward (and before she was seen by the ward doctors), she suddenly deteriorated and her blood pressure fell. This wasn’t noticed as quickly as it might have been had she stayed in A&E as the ward nurses were so rushed off their feet (two trained nurses having to look after 24 demanding patients).

She had been rushed out of A&E to get her to a ward so that she wouldn’t break the government’s 4-hour target (and because the A&E department has not got the resources to continue safely caring for patients for longer than a few hours in addition to seeing all the new ones constantly coming through the doors). I also had to pass responsibility over to the other doctors before her blood tests were back and before a definitive diagnosis was made. I later learned that she had been anaemic, which had put stress on her heart, and that she then ended up on the high-dependency ward, needing a blood transfusion.

For a while it was touch and go as to whether she could be stabilised. I couldn’t help wondering whether, if she had remained in A&E, under our care, all these problems could have been treated sooner and the complications avoided. However, this was not possible as, apparently, I had more pressing priorities. My next job was to go and see a bloke who had called an ambulance to get his ingrown toenail looked at and who had been waiting for 3 hours. He had, incidentally, had this problem for five weeks and wanted it (in his words) ‘sorted out now, as I’m off to Ibiza tomorrow, mate’.

I felt really frustrated. It didn’t need to be like this. Why does the ‘system’ have to impede me from caring for my sick patients and make me worry about figures and targets instead?

When you are surrounded by death and disease, aggressive and drunk patients, and nurses (male and female) trying constantly to flirt with you, it can make working in A&E an interesting and often stressful environment. However, it is the management problems and the effects of the NHS reforms, implemented without thinking about the possibilities of unintended consequences that really drive doctors and nurses mad. More importantly, they distort clinical priorities and can damage patient care. Surely this is not what the government intended? How have we drifted away from the original ideals of the NHS?

In July 1948, Nye Bevan presided over the creation of the NHS. It is a service that provides free care based on need and not ability to pay; to care for us from the cradle to the grave. It was the envy of the world and the greatest example of social policy this country has ever implemented. It is a wonderful institution that needs protecting and nurturing. Its desire to protect health and not profits means that its efficiency could outstrip that of any other health system in the world. The very thought of working for it filled me with pride.

By 1997, years of underfunding had left the NHS in a perilous state. Massive influxes of money from Blair and Brown poured in, which helped bring in some great improvements in service and much-needed reforms. This is especially true in A&E, where things have improved greatly from the days of patients spending days in corridors on trolleys waiting for a bed. The target brought in was a 4-hour rule stating that 98 percent of people have to be seen and admitted or discharged within 4 hours. Initially, it was a necessary but blunt tool, which effectively brought about urgently needed change. However, its lack of subtlety and implementation without resort to common sense is now impeding care and distorting priorities.

Despite the enormous sums of money that have been spent, for the NHS as a whole the overall benefits have been underwhelming. In the last few years, the government has managed to demoralise a significant number of hospital workers despite these huge increases in resources. To try and get ‘better value for money’ targets have been implemented and reforms made that threaten the structure, efficiency and ethos of the NHS, driving it away from cooperation and caring towards incoherence and profit making. For those of us who believe in the idea of collectivism enshrined in the NHS, it is a worrying time. It is an especially worrying time if you live near a hospital that is under threat of closure or losing its A&E in the name of ‘reforms’.

These worries about what is happening to the NHS (and in particular A&E) combined with the general demands of the job, can sometimes make me feel a bit stressed. Many people cope with this by drinking; however, I usually have to stop after a pint, as I start to feel sick and get a rash. Instead I started ranting to my friends and moaning to my wife: she started to threaten divorce and my friends seemed to invite me out less and less. So, in an attempt to save my sanity and marriage, I turned to writing down my frustrations with the job. A cathartic form of literary therapy.

That is, in part, what this book is about. It is a collection of stories written to try and explain what working in A&E is really like. It is not just about the frustrations – far from it. I have also tried to provide a small indication of the buzz I get from work and the amusement and banter that can be found there, including the dark humour that is used to cope with the stress of the job. I have tried to describe the joy I get from observing the eccentricities of the human condition and the fascinating little ironies life throws upon us. I have, in addition, tried to cover more serious aspects of the problems facing today’s NHS and A&E departments in particular. All the stories are typical of ones retold in staff coffee-rooms up and down the country. They are based on events that have happened to me, or colleagues, working in various hospitals throughout the last six years. However, details have been changed and the stories described are often an amalgam of many similar incidents rather than one specific case. If you think you recognise a clinical situation or problem, it is probably because it is repeated daily in all A&E departments.

This book is certainly not a whistle-blowing exercise, as the situations described are universal problems and not specific to one hospital. I certainly feel that the departments I have worked in are good and the consultants have been supportive. The way they manage to provide top-quality clinical care despite the management concerns occurring in the background, provide me with appropriate role models. Neither is this book a blog as such (although the idea started out as a blog) – there is no real-time order to the various passages. There is no underlying story and neither are the stories arranged into any theme. It is just a random selection of events and experiences as an A&E doctor.

I hope you enjoy reading it – both the amusing and sarcastic bits and the ones where I am being serious. I hope to inform you what really goes on in your local A&E and what the people working there are going through, so that if you happen to need our services, you will understand when things don’t work as smoothly as perhaps they should. The views and ideas in the book are my own and are not endorsed by any political organisation or pressure group. I am not a politician or a manager, but I do work on the ‘coal face’ of the NHS and can see its problems.

I don’t think the NHS is having its best year ever. I think all the recent reforms and targets and private sector involvement are really making things go a bit ‘tits up’. I want to share with you some of my concerns and how they affect my working life, as well as showing you the real highs and lows of life as an A&E doctor. Thank you for reading.

Dr Nick Edwards, July 2007

P.S. For those of you who want a quick summary of what life is like working in A&E, without having to read the book, then here goes. It is a bit like what you see on TV programmes such as ER, but with less sex and more paper work. I, unfortunately, do not look like George Clooney either – more like Charlie out of Casualty. I have also never asked for a ‘chem 20 stat’ and the medical students are not usually as beautiful or as helpful as the ones depicted in ER.

A sign the world has gone mad?

What was happening to my patients today? They seemed to be getting lost when I sent them for X-ray. I’d given the same directions as normal, there had been no secret muggers hiding in the hospital corridors and, as far as I know, no problems with space – time dimensions in our particular corner of the universe.

I went to X-ray to investigate. I found it quickly because I knew the way. However, I looked for the signs for X-ray and they were gone. The nice, old-fashioned and slightly worn signs had gone; they had been replaced by a sign saying ‘Department of Diagnostic Imaging’. What the hell? I know what it means, but only just, and only because I have been inundated by politically correct ‘shit-speak’ for a number of years. What a pointless waste of money; to satisfy some manager, they replaced a perfectly good sign with one that means bugger all to 90 percent of people. Why don’t they change the toilet sign to ‘Department of Faecal and Urinary Excrement’ or the cafe to ‘Calorific Enhancement Area’? Who makes these decisions? Who is employed to do such pointless stuff? Why? Why?? Why???

I needed a caffeinated beverage in a disposable single-use container – management-speak for shit NHS/Happy Shopper instant coffee. I went to sit in the ‘Relaxation, Rest and Reflection Room’, previously known as the staff room. There, the nurses were moaning that one of their colleagues had called in sick tonight and to save money their shift would not be covered by an agency nurse. In A&E, staff shortages can seriously undermine the safety of patient care.

I am sure this genius plan was decided by some personnel manager who I doubt has ever seen a patient, cannula or trolley, and is therefore obviously an expert at making nursing planning decisions. So we have a hospital that can fund unnecessary new signs, but not replace nurses when they are off sick. So, tonight who is going to go looking for the patients when they get lost en route to the Department of Diagnostic Imaging?

Management madness

If politicians tell you that by instilling the ethos of the private sector we can improve the efficiency of the NHS and improve patient care, then let me tell you that is rubbish. What is needed is good old-fashioned common sense and cooperation. Unfortunately, this is difficult to put on a balance sheet.

Let me give you an example that really upset me. An old man who had Alzheimer’s and was in a nursing home tripped and fell and banged his head. He was on his way to the toilet, but had forgotten that he normally needed a frame and a nurse to help him. He sustained a laceration to his forehead. He needed five stitches, and then to go home. He arrived at 11 p.m.

It was a very quiet night. I was asked to see him straight away as the nurse in charge knew that we could discharge him back very quickly. Fifteen minutes later he was ready for discharge and the ambulance crew that had brought him in were still having a chat and coffee with us all. The charge nurse asked if they would take him back and they didn’t mind at all. They called the coordinator at the control centre (someone who has never worked on an ambulance). He told them that they couldn’t take the patient back to his nursing home, as our hospital (to save money) had changed the terms of contract with the ambulance trust and no non-essential transfers were to be done after 11 p.m. The ambulance man protested and explained that there were three ambulances in the locality, all with their feet up. He said he didn’t mind doing it as it was for the old man’s benefit. Control responded with a statement about breaking contractual obligations, setting a precedent and influencing future contract negotiations.

Further protests ensued. The man was not safe to get a taxi on his own but was still well enough to go back to his nursing home. There was a willing crew who were free at the time and I couldn’t see the problem. I tried to intervene and told control about how the man was confused and distressed about coming into hospital. I explained that staying in hospital until 9 a.m. the next morning would make him worse. However, I was told that the 3 percent funding shift resource allocation caused by the contract change had meant that they could no longer do goodwill gestures such as I had requested.

It was ridiculous. For no good reason beyond disjointed management decisions – made introspectively, without thinking about the consequence for the whole NHS – this man had to stay in an A&E ward for 10 hours. He became very upset and distressed. A&E later became much busier and our nurses didn’t have time to take him to the toilet and so he soiled himself. He screamed all night because he was confused and disorientated in this strange place and the patients in the bed next to him slept very poorly. I was then asked to prescribe sedatives for the patients in the A&E ward, and for him!

I just don’t understand what is happening in management; I don’t think that management understands what is happening on the A&E ‘shop floor’. I found out from one of the senior A&E nurses that the contract decision was changed to save a very small amount of money. Managers would have slapped themselves on their backs for their ‘efficiency’ savings to the transport budget, but not realised that it would not have saved the hospital, or the NHS as a whole, a single penny (the patient still needed to go back in the morning!).

I was annoyed with our managers, but why did the ambulance control man act in the way he did? A few years ago, the crews would have taken these patients back if they were quiet – contract or no contract – for the good for the patient. I suppose nowadays people are instructed to do stuff only if it is for the good of the targets and common sense has flown out of the window.

I got very stressed and angry about this. After a while the junior doctor working with me asked why I was so irate. I explained that, apart from an irate personality disorder and the fact that ranting is my form of therapy, I was genuinely upset. Apart from my lovely family and useless football team, the things I care most about are my patients’ care and the state of the NHS. It upsets me that crappy management decisions done in the name of ‘efficiency’ bugger up both.

P.S. If there are any politicians/managers wanting to see the actual effect of NHS policies (both good and bad) on patient care, please ask your local A&E department if you can spend a night working alongside the doctors and nurses. You will learn more about the problems in that one night, than you ever will from looking at a balance sheet or ‘throughput’ data that A&E departments send their hospital managers.

P.P.S. If you think I will ever talk about how awful things are, please be assured that some things have improved dramatically over the last few years, it is just that I want them to continue improving and not get worse again. Also, when there are no problems, I do not get angry and so do not feel the need to write. So, if you think everything I say is biased, then, yes, you are right. But biased for the right reason: to try and get things changed for the better … and to help with my stress relief.

Treating your own family

It is a well-known fact that you should not be a doctor for your family. This is true. I certainly found out how true last night …

It was the quietest night we had had for a long time. A&E was empty when my wife’s grandpa arrived. He is in his 90s, demented, and spending the last few years of his life in a confused state in a nursing home. The staff at his nursing home had called an ambulance as he was more short of breath than usual.

I got the other doctor to see him and told them all his problems. I explained that on his previous admission, the consultant had declared him ‘Not for Resus’ (i.e. if his heart were to stop, then it would not be appropriate to try to restart it with cardiopulmonary resuscitation – CPR). This was the right thing because his quality of life was so poor. In all honesty, I just hoped for his sake that he would pass away peacefully in his sleep. I had a chat with him and then, when he fell asleep, I left to get a drink. It was very quiet in A&E and he was the only one left in the department.

I was dozing in the coffee room, when the alarm call came through the intercom. ‘Cardiac arrest, Resus’. I ran there past where Grandpa was meant to be. He wasn’t there. For Christ’s sake! Why had they moved him into the Resus room, and why were they doing something futile and cruel? I was livid.

I ran into the Resus room. Everything went into slow motion. There was a nurse jumping up and down on an elderly man’s chest and the doctor ventilating his lungs. I was furious. ‘Let him die in a dignified way and not with broken ribs,’ I thought.

‘STOP. STOP. BLOODY HELL, STOP’, I screamed.

‘It’s not your grandpa, Nick. He has gone for an X-ray. This bloke just collapsed in reception about twenty seconds ago.’

‘CONTINUE, CONTINUE’, I screamed back. ‘BLOODY HELL, CONTINUE.’

Ridiculously embarrassed, I managed to regain my composure and lead a successful cardiac resuscitation. We got back a pulse and called the anaesthetists to take over his breathing. He went to ICU (the intensive care unit) and three weeks later was discharged to lead a normal life. Thank God everyone ignored my advice to stop.

Meanwhile, my wife’s grandpa was sent back to his home the next day and is still in the same sorry way.

Dealing with threatening patients

I get scared sometimes at work. I work in a rather tough town – even the muggers go round in pairs. Consequently, we get some rather tough patients. Give them some alcohol and they become a little hostile. Add the stress of waiting 3 hours and 59 minutes and they become aggressive. The fact that they are often in A&E because they lost a fight sometimes results in them looking for revenge – and A&E staff are often the target.

I am a not a ‘weed’ but I am not sure that I could handle myself if I ever got into a proper fight. With a lack of any training in self-defence, and an A&E security guard that my Nan could ‘have’, you sometimes feel a little vulnerable. I have never been assaulted but I know a number of colleagues who have. The BBC programme Panorama investigated this violence and reported that a NHS worker gets attacked every 7 minutes (for more information see: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/panorama/6383781.stm). However, much of the ‘violence’ results from the confusion caused by medical problems. I have been bitten by a lady in her 80s who was short of oxygen. It wasn’t her fault – it was probably mine – I should have been more careful. When she was better she was the most beautifully placid person in the world. These are not the type of ‘violent’ patients that upset me. It is the aggressive, bullying types who know all their rights but have no sense of respect that irk me and make my job scary at times.

Last night I was at the desk, writing my notes, when a drunk and aggressive man came up to me and was forcibly complaining that I was delaying his treatment because I was being anti-Moldovan. (Maybe I need to go on a cultural awareness course, because I didn’t even realise he was Moldovan or, more to the point, where in fact Moldovia is.) All I knew was that he was a man who did not need to be seen before the bloke who need 15 sutures for a bottling injury and who was bleeding profusely.

The patient became very aggressive and angry. As he started to walk menacing towards me, I started to apologise profusely (as well as sweat profusely). Experience has taught me that this often stops aggressive people in their tracks as they are frequently expecting a fight back. Worth a try, I thought …

‘I am very sorry sir, but we are very busy tonight. We see people in order of priority and not time order, I am afraid.’

He kept shouting insults and making demands. He was not happy with his wait. Eventually, it was obvious my tactic was not working. I just wanted to ask him to leave in a firm way, but I was too scared of him. Luckily, I could see that there were two policemen in the waiting room, who had ‘smelt’ trouble and had started to walk towards me. I breathed a sigh of relief and suddenly found lots of bravado.

‘I am very sorry’, I said, before adding ‘for having to take your insults. I have been working ridiculously hard all night and don’t deserve your language or behaviour.’

My temper now started to rise. ‘If you dare speak to anyone like this again you will not be treated. Now sit down and be quiet and wait your turn. If you have a problem with this, then leave.’

I pointed to the door and felt like a brave warrior who had just defended his tribe of A&E doctors and nurses, but I knew that I was a warrior of the type that only stands up for himself in the presence of a policeman. In reality, I am still a scared wimp who is polite to rude and threatening patients purely because I am afraid of breaking my General Medical Council code of ethics of treating people in a non-judgmental way … and because I don’t want my head kicked in.

On one occasion when someone would not stop complaining and became verbally threatening, my colleague took them to the door of the resuscitation room to show them what we were doing and why his wait was so long. The complainer commented that it wasn’t his problem and later wrote a complaint letter about the psychological upset he had been subjected to. Unfortunately, my colleague has not felt compelled to be brave enough to do this again and now just ends up apologising behind gritted teeth.

It is very difficult dealing with violence in hospitals. What do you do with an injured patient who needs your care but is threatening? It is easy if they have assaulted someone as you can call the police. But bullying and threatening behaviour is difficult to deal with. Personally, I think it is time that in addition to patients having more and more rights, NHS workers had more rights and protection too – they certainly need it. Unfortunately, we have become too politically correct. The modern NHS thinks of patients as customers and we are encouraged to believe that ‘the customer is always right’ but sometimes that is just not the case.

No notes

The ambulance pulled up and the paramedic came out. ‘Nick, we need to take him to Resus. His pulse is only 30.’ It seemed a reasonable request so I went off to Resus to see him.

The patient was 80, lived alone and had no close relatives. He had dementia and received care four times a day. The carer had called the ‘out of hours’ GP because his catheter was blocked, he couldn’t pass urine and his stomach was starting to ache. The GP told them to come to A&E as the out-of-hours service was too busy. A much better course of action would have been for them to go and ‘unblock’ the catheter, but that is a moan for another day.

I examined him and, apart from having a blocked catheter, the main problem was his pulse of 30 (normal is about 60). His ECG showed ‘complete heart block’, a condition that makes the heart beat very slowly. His blood pressure was normal, so it wasn’t an immediate life-threatening event, but heart block can be very serious, particularly if it is a new condition.

I asked the patient about it. He didn’t really understand what I was talking about. The carer didn’t know. I phoned the out- of-hours GP, but they can’t access regular GP notes outside working hours. The carer didn’t know anything about his heart condition, and there were no relatives available to ask. I asked our receptionists to get his old notes urgently as I needed to know what was going on. Would he need to go to the cardiac unit urgently or could he go home?

The A&E receptionist said that she couldn’t get hold of the notes. They were in a secretary’s office awaiting ‘typing’ and no-one could get hold of them. I moved on up the food chain and called the hospital ‘Site Manager’, the most senior person present in the hospital in the evening.

‘I need them urgently’, I pleaded.

‘Unfortunately, we can’t,’ I was informed.

‘It is life threatening. Please can we get them?’

‘Computer says no’ (OK, she didn’t actually say that, but it was something to that effect).

I had to practise safe medicine, so I referred him to the medical doctors to be monitored on the cardiac care unit (CCU). I explained that I thought it was a chronic problem, but that I wasn’t prepared to take the risk. They agreed and he went to the CCU.

In the morning, when the cardiologists were debating what to do, the GP was called and the hospital notes obtained. It was soon found that he had had this condition for five years. He had been referred for a pacemaker, but had refused one as the condition had never bothered him. The GP also explained that when the patient had been ‘with it’ he had always said that he never wanted to go for a hospital for a pacemaker. This pretty much swung the treatment plan into discharging him back home.

However, this visit put him at risk of hospital-acquired infection, and took up the last bed on the CCU, which might have prevented someone who would have genuinely benefited from coming to CCU from being there. And why? Because we couldn’t get hold of his old notes outside office hours. It is so frustrating to work in a system like this – what a waste of money. This happens time after time after time – unnecessary admissions occur, expensive tests are repeated and patients are not being cared for properly – all because of poor accessibility of patient records.