скачать книгу бесплатно

And there – since else were all things else prov’d naught –

Bestower and hallower of all things: I will have Thee.

—Thee, and hawthorn time. For in that new birth though all

Change, you I will have unchang’d: even that dress,

So fall’n to your hips as lapping waves should fall:

You, cloth’d upon with your beauty’s nakedness.

The line of your flank: so lily-pure and warm:

The globéd wonder of splendid breasts made bare:

The gleam, like cymbals a-clash, when you lift your arm;

And the faun leaps out with the sweetness of red-gold hair.

My dear – my tongue is broken: I cannot see:

A sudden subtle fire beneath my skin

Runs, and an inward thunder deafens me,

Drowning mine ears: I tremble. – O unpin

Those pins of anachite diamond, and unbraid

Those strings of margery-pearls, and so let fall

Your python tresses in their deep cascade

To be your misty robe imperial—

The beating of wings, the gallop, the wild spate,

Die down. A hush resumes all Being, which you

Do with your starry presence consecrate,

And peace of moon-trod gardens and falling dew.

Two are our bodies: two are our minds, but wed.

On your dear shoulder, like a child asleep,

I let my shut lids press, while round my head

Your gracious hands their benediction keep.

Mistress of my delights; and Mistress of Peace:

O ever changing, never changing, You:

Dear pledge of our true love’s unending lease,

Since true to you means to mine own self true—

I will have gold and jewels for my delight:

Hyacinth, ruby, and smaragd, and curtains work’d in gold

With mantichores and what worse shapes of fright

Terror Antiquus spawn’d in the days of old.

Earth I will have, and the deep sky’s ornament:

Lordship, and hardship, and peril by land and sea—

And still, about cock-shut time, to pay for my banishment,

Safe in the lowe of the firelight I will have Thee.

Half blinded with tears, I read the stanzas and copied them down. All the while I was conscious of the Señorita’s presence at my side, a consciousness from which in some irrational way I seemed to derive an inexplicable support, beyond comprehension or comparisons. These were things which by all right judgement it was unpardonable that any living creature other than myself should have looked upon. Yet of the lightness of her presence (more, of its deep necessity), my sense was so lively as to pass without remark or question. When I had finished my writing, I saw that she had not moved, but remained there, very still, one hand laid lightly on the bedpost at the foot of the bed, between the ears of the great golden hippogriff. I heard her say, faint as the breath of night-flowers under the stars: ‘The fabled land of ZIMIAMVIA. Is it true, will you think, which poets tell us of that fortunate land: that no mortal foot may tread it, but the blessed souls do inhabit it of the dead that be departed: of them that were great upon earth and did great deeds when they were living, that scorned not earth and the delights and the glories of earth, and yet did justly and were not dastards nor yet oppressors?’

‘Who knows?’ I said. ‘Who dares say he knows?’

Then I heard her say, in her voice that was gentler than the glow-worm’s light among rose-trees in a forgotten garden between dewfall and moonrise: Be content. I have promised and I will perform.

And as my eyes rested on that strange woman’s face, it seemed to take upon itself, as she looked on Lessingham dead, that unsearchable look, of laughter-loving lips divine, half closed in a grave expectancy, of infinite pity, infinite patience, and infinite sweetness, which sits on the face of Praxiteles’s Knidian Aphrodite.

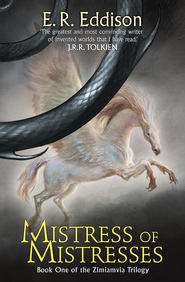

ZIMIAMVIA (#ulink_86b70eec-43e6-53b0-b764-cd19508b086f)

PRINCIPAL PERSONS

LESSINGHAM

BARGANAX

FIORINDA

ANTIOPE

I A SPRING NIGHT IN MORNAGAY (#ulink_e34d3c11-6560-5bd5-b31e-5dd9ff67d92f)

A COMMISSION OF PERIL • THE THREE KINGDOMS MASTERLESS • POLICY OF THE VICAR • THE PROMISE HEARD IN ZIMIAMVIA.

‘BY all accounts, ’twas to give him line only,’ said Amaury; ‘and if King Mezentius had lived, would have been war between them this summer. Then he should have been boiled in his own syrup; and ’tis like danger now, though smaller, to cope the son. You do forget your judgement, I think, in this single thing, save which I could swear you are perfect in all things.’

Lessingham made no answer. He was gazing with a strange intentness into the wine which brimmed the crystal goblet in his right hand. He held it up for the bunch of candles that stood in the middle of the table to shine through, turning the endless stream of bubbles into bubbles of golden fire. Amaury, half facing him on his right, watched him. Lessingham set down the goblet and looked round at him with the look of a man awaked from sleep.

‘Now I’ve angered you,’ said Amaury. ‘And yet, I said but true.’

As a wren twinkles in and out in a hedgerow, the demurest soft shadow of laughter came and went in Lessingham’s swift grey eyes. ‘What, were you reading me good counsel? Forgive me, dear Amaury: I lost the thread on’t. You were talking of my cousin, and the great King, and might-a-beens; but I was fallen a-dreaming and marked you not.’

Amaury gave him a look, then dropped his eyes. His thick eyebrows that were the colour of pale rye-straw frowned and bristled, and beneath the sunburn his face, clear-skinned as a girl’s, flamed scarlet to the ears and hair-roots, and he sat sulky, his hands thrust into his belt at either side, his chin buried in his ruff. Lessingham, still leaning on his left elbow, stroked the black curls of his mustachios and ran a finger slowly and delicately over the jewelled filigree work of the goblet’s feet. Now and again he cocked an eye at Amaury, who at last looked up and their glances met. Amaury burst out laughing. Lessingham busied himself still for a moment with the sparkling, rare, and sunset-coloured embellishments of the goldsmith’s art, then, pushing the cup from him, sat back. ‘Out with it,’ he said; ‘’tis shame to plague you. Let me know what it is, and if it be in my nature I’ll be schooled.’

‘Here were comfort,’ said Amaury; ‘but that I much fear ’tis your own nature I would change.’

‘Well, that you will never do,’ answered he.

‘My lord,’ said Amaury, ‘will you resolve me this: Why are we here? What waiting for? What intending?’

Lessingham stroked his beard and smiled.

Amaury said. ‘You see, you will not answer. Will you answer this, then: It is against the nature of you not to be rash, and against the condition of rashness not to be ’gainst all reason; yet why (after these five years that I’ve followed you up and down the world, and seen you mount so swiftly the degrees and steps of greatness that, in what courts or princely armies soever you might be come, you stuck in the eyes of all as the most choice jewel there): why needs must you, with the wide world to choose from, come back to this land of Rerek, and, of all double-dealers and secretaries of hell, sell your sword to the Vicar?’

‘Not sell, sweet Amaury,’ answered Lessingham. ‘Lend. Lend it in cousinly friendship.’

Amaury laughed. ‘Cousinly friendship! Give us patience! With the Devil and him together on either hand of you!’ He leapt up, oversetting the chair, and strode to the fireplace. He kicked the logs together with his heavy riding-boots, and the smother of flame and sparks roared up the chimney. Turning about, his back to the fire, feet planted wide, hands behind him, he said: ‘I have you now in a good mood, though ’twere over much to hope you reasonable. And now you shall listen to me, for your good. You do know me: am I not myself by complexion subject to hasty and rash motions? Yet I it is must catch at your bridle-rein; for in good serious earnest, you do make toward most apparent danger, and no tittle of advantage to be purchased by it. Three black clouds moving to a point; and here are you, in the summer and hunting-season of your youth, lying here with your eight hundred horse these three days, waiting for I know not what cat to jump, but (as you have plainly told me) of a most set obstinacy to tie yourself hand and heart to the Vicar’s interest. You have these three months been closeted in his counsels: that I forget not. Nor will I misprise your politic wisdom: you have played chess with the Devil ere now and given him stalemate. But ’cause of these very things, you must see the peril you stand in: lest, if by any means he should avail to bring all things under his beck, he should then throw you off and let you hop naked; or, in the other event, and his ambitious thoughts should break his neck, you would then have raised up against yourself most bloody and powerful enemies.

‘Look but at the circumstance. This young King Styllis is but a boy. Yet remember, he is King Mezentius’ son; and men look not for lapdog puppies in the wolf’s lair, nor for milksops to be bred up for heirship to the crown and kingdom of Fingiswold. And he is come south not to have empty homage only from the regents here and in Meszria, but to take power. I would not have you build upon the Duke of Zayana’s coldness to his young brother. True, in many families have the bastards been known the greater spirits; and you did justly blame the young King’s handling of the reins in Meszria when (with a warmth from which his brother could not but take cold) he seemed to embrace to his bosom the lord Admiral, and in the same hour took away with a high hand from the Duke a great slice of his appanage the King their father left him. But though he smart under this neglect, ’tis not so likely he’ll go against his own kindred, nor even stand idly by, if it come to a breach ’twixt the King and the Vicar. What hampers him today (besides his own easeful and luxurious idleness) is the Admiral and those others of the King’s party, sitting in armed power at every hand of him in Meszria; but let the cry but be raised there of the King against the Vicar, and let Duke Barganax but shift shield and declare himself of’s young brother’s side, why then you shall see these and all Meszria stand in his firm obedience. Then were your cousin the Vicar ta’en betwixt two millstones; and then, where and in what case are you, my lord? And this is no fantastical scholar’s chop-logic, neither: ’tis present danger. For hath not he for weeks now set every delay and cry-you-mercy and procrastinating stop and trick in the way of a plain answer to the young King’s lawful demand he should hand over dominion unto him in Rerek?’

‘Well,’ said Lessingham, ‘I have listened most obediently. You have it fully: there’s not a word to which I take exceptions. Nay I admire it all, for indeed I told you every word of it myself last night.’

‘Then would to heaven you’d be advised by’t,’ said Amaury. ‘Too much light, I think, hath made you moon-eyed.’

‘Reach me the map,’ said Lessingham. For the instant there was a touch in the soft bantering music of his voice as if a blade had glinted out and in again to its velvet scabbard. Amaury spread out the parchment on the table, and they stood poring over it. ‘You are a wiser man in action, Amaury, in natural and present, than in conceit; standing still, stirs your gall up: makes you see bugs and hobthrushes round every corner. Am I yet to teach you I may securely dare what no man thinks I would dare, which so by hardness becometh easy?’

Lessingham laid his forefinger on this place and that while he talked. ‘Here lieth young Styllis with’s main head of men, a league or more be-east of Hornmere. ’Tis thither he hath required the Vicar come to him to do homage of this realm of Rerek, and to lay in his hands the keys of Kessarey, Megra, Kaima, and Argyanna, in which the King will set his own captains now. Which once accomplished, he hath him harmless (so long, at least, as Barganax keep him at arm’s length); for in the south there they of the March openly disaffect him and incline to Barganax, whose power also even in this northern ambit stands entrenched in’s friendship with Prince Ercles and with Aramond, spite of all supposed alliances, respects, and means, which bind ’em tributary to the Vicar.

‘But now to the point of action; for ’tis needful you should know, since we must move north by great marches, and that this very night. My noble cousin these three weeks past hath, whiles he amused the King with’s chaffer-talk of how and wherefore, opened unseen a dozen sluices to let flow to him in Owldale men and instruments of war, armed with which strong arguments (I have it by sure intelligence but last night) he means tomorrow to obey the King’s summons beside Hornmere. And, for a last point of logic, in case there be falling out between the great men and work no more for learned doctors but for bloody martialists, I am to seize the coast-way ’twixt the Swaleback fells and Arrowfirth and deny ’em the road home to Fingiswold.’

‘Deny him the road home?’ said Amaury. ‘’Tis war, then, and flat rebellion?’

‘That’s as the King shall choose. And so, Amaury, about it straight. We must saddle an hour before midnight.’

Amaury drew in his breath and straightened his back. ‘An hour to pack the stuff and set all in marching trim: and an hour before midnight your horse is at the door.’ With that, he was gone.

Lessingham scanned the map for yet a little while, then let it roll itself up. He went to the window and threw it open. There was the breath of spring in the air and daffodil scents: Sirius hung low in the south-west.

‘Order is ta’en according to your command,’ said Amaury suddenly at his side. ‘And now, while yet is time to talk and consider, will you give me leave to speak?’

‘I thought you had spoke already,’ said Lessingham, still at the window, looking round at him. ‘Was all that but the theme given out, and I must now hear point counterpoint?’

‘Give me your sober ear, my lord, but for two minutes together. You know I am yours, were you bound for the slimy strand of Acheron. Do but consider; I think you are in some bad ecstasy. This is worse than all: cut the lines of the King’s communications northward, in the post of main danger, with so little a force, and Ercles on your flank ready to stoop at us from his high castle of Eldir and fling us into the sea.’

‘That’s provided for,’ said Lessingham: ‘he’s made friends with as for this time. Besides, he and Aramond are the Duke’s dogs, not the King’s; ’tis Meszria, Zayana, all their strings hold unto; north winds bring ’em the cough o’ the lungs. Fear not them.’

Amaury came and leaned himself too on the window-sill, his left elbow touching Lessingham’s. After a while he said, low and as if the words were stones loosed up one by one with difficulty from a stiff clay soil, ‘’Fore heaven, I must love you; and it is a thing not to be borne that your greatness should be made but this man’s cat’s-paw.’

Sirius, swinging lower, touched the highest tracery of a tall ash-tree, went out like a blown-out candle behind a branch, and next instant blazed again, a quintessential point of diamond and sapphire and emerald and amethyst and dazzling whiteness. Lessingham answered in a like low tone, meditatively, but his words came light on an easy breath: ‘My cousin. He is meat and drink to me. I must have danger.’

They abode silent at that window, drinking those airs more potent than wine, and watching, with a deep compulsive sense of essence drawn to essence, that star’s shimmer of many-coloured fires against the velvet bosom of the dark; which things drew and compelled their beings, as might the sweet breathing nearness of a woman lovely beyond perfection and deeply beyond all soundings desired. Lessingham began to say slowly, ‘That was a strange trick of thought when I forgot you but now, and forgot my own self too, in those bubbles which in their flying upward signify not as the sparks, but that man is born for gladness. For I thought there was a voice spake in my ear in that moment and I thought it said, I have promised and I will perform. And I thought it was familiar to me beyond all familiar dear lost things. And yet ’tis a voice I swear I never heard before. And like a star-gleam, it was gone.’

The gentle night seemed to turn in her sleep. A faint drumming, as of horse-hooves far away, came from the south. Amaury stood up, walked over to the table, and fell to looking at the map again. The beating of hooves came louder, then on a sudden faint again. Lessingham said from the window, ‘There’s one rideth hastily. Now a cometh down to the ford in Killary Bottom, and that’s why we lose the sound for awhile. Be his answers never so good, let him not pass nor return, but bring him to me.’

II THE DUKE OF ZAYANA (#ulink_c08ba25c-2dca-5a44-a88e-01907a517b6a)

PORTRAIT OF A LADY • DOCTOR VANDERMAST • FIORINDA: ‘BITTER-SWEET’ • THE LYRE THAT SHOOK MITYLENE

THE third morning after that coming of the galloping horseman north to Mornagay, Duke Barganax was painting in his privy garden in Zayana in the southland: that garden where it is everlasting afternoon. There the low sun, swinging a level course at about that pitch which Antares reaches at his highest southing in an English May-night, filled the soft air with atomies of sublimated gold, wherein all seen things became, where the beams touched them, golden: a golden sheen on the lake’s unruffled waters beyond the parapet, gold burning in the young foliage of the oak-woods that clothed the circling hills; and, in the garden, fruits of red and yellow gold hanging in the gold-spun leafy darkness of the strawberry-trees, a gilding shimmer of it in the stone of the carven bench, a gilding of every tiny blade on the shaven lawn, a glow to deepen all colours and to ripen every sweetness: gold faintly warming the proud pallour of Fiorinda’s brow and cheek, and thrown back in sudden gleams from the jet-black smoothnesses of her hair.

‘Would you be ageless and deathless for ever, madam, were you given that choice?’ said the Duke, scraping away for the third time the colour with which he had striven to match, for the third time unsuccessfully, the unearthly green of that lady’s eyes.

‘I am this already,’ answered she with unconcern.

‘Are you so? By what assurance?’

‘By this most learn’d philosopher’s, Doctor Vandermast.’

The Duke narrowed his eyes first at his model then at his picture: laid on a careful touch, stood back, compared them once more, and scraped it out again. Then he smiled at her: ‘What? Will you believe him? Do but look upon him where he sitteth there beside Anthea, like winter wilting before Flora in her pride. Is he one to inspire faith in such promises beyond all likelihood and known experiment?’

Fiorinda said: ‘He at least charmed you this garden.’

‘Might he but charm your eyes,’ said the Duke, ‘to some such unaltering stability, I’d paint ’em; but now I cannot. And ’tis best I cannot. Even for this garden, if ’twere as you said, madam (or worse still, were you yourself so), my delight were poisoned. This eternal golden hour must lose its magic quite, were we certified beyond doubt or heresy that it should not, in the next twinkling of an eye, dissipate like mist and show us the work-a-day morning it conceals. Let him beware, and if he have art indeed to make safe these things and freeze them into perpetuity, let him forbear to exercise it. For as surely as I have till now well and justly rewarded him for what good he hath done me, in that day, by the living God, I will smite off his head.’

The Lady Fiorinda laughed luxuriously, a soft, mocking laugh with a scarce perceptible little contemptuous upward nodding of her head, displaying the better with that motion her throat’s lithe strong loveliness. For a minute, the Duke painted swiftly and in silence. Hers was a beauty the more sovereign because, like smooth waters above a whirlpool, it seemed but the tranquillity of sleeping danger: there was a taint of harsh Tartarean stock in her high flat cheekbones, and in the slight upward slant of her eyes; a touch of cruelty in her laughing lips, the lower lip a little too full, the upper a little too thin; and in her nostrils, thus dilated, like a beautiful and dangerous beast’s at the smell of blood. Her hair, parted and strained evenly back on either side from her serene sweet forehead, coiled down at last in a smooth convoluted knot which nestled in the nape of her neck like a black panther asleep. She wore no jewel nor ornament save two escarbuncles, great as a man’s thumb, that hung at her ears like two burning coals of fire. ‘A generous prince and patron indeed,’ she said; ‘and a most courtly servant for ladies, that we must rot tomorrow like the aloe-flower, and all to sauce his dish with a biting something of fragility and non-perpetuity.’

The Countess Rosalura, younger daughter of Prince Ercles, new-wed two months ago to Medor, the Duke’s captain of the bodyguard, had risen softly from her seat beside her lord on the brink of a fountain of red porphyry and come to look upon the picture with her brown eyes. Medor followed her and stood looking beside her in the shade of the great lime-tree. Myrrha and Violante joined them, with secret eyes for the painter rather than for the picture: ladies of the bedchamber to Barganax’s mother, the Duchess of Memison. Only Anthea moved not from her place beside that learned man, leaning a little forward. Her clear Grecian brow was bent, and from beneath it eyes yellow and unsearchable rested their level gaze upon Barganax. Her fierce lips barely parted in the dimmest shadow or remembrance of a smile. And it was as if the low golden beams of the sun, which in all things else in that garden wrought transformation, met at last with something not to be changed (because it possessed already a like essence with their own and a like glory), when they touched Anthea’s hair.

‘There, at last!’ said the Duke. ‘I have at last caught and pinned down safe on the canvas one particular minor diabolus of your ladyship’s that hath dodged me a hundred times when I have had him on the tip of my brush; him I mean that peeks and snickers at the corner of your mouth when you laugh as if you would laugh all honesty out of fashion.’

‘I laugh none out of fashion,’ she said, ‘but those that will not follow the fashions I set ’em. May I rest now?’

Without staying for an answer, she rose and stepped down from the stone plinth. She wore a coat-hardy, of dark crimson satin. From shoulder to wrist, from throat to girdle, the soft and shining garment sat close like a glove, veiling yet disclosing the breathing loveliness which, like a rose in crystal, gave it life from within. Her gown, of the like stuff, revealed when she walked (as in a deep wood in summer, a stir of wind in the tree-tops lets in the sun) rhythms and moving splendours bodily, every one of which was an intoxication beyond all voluptuous sweet scents, a swooning to secret music beyond deepest harmonies. For a while she stood looking on the picture. Her lips were grave now, as if something were fallen asleep there; her green eyes were narrowed and hard like a snake’s. She nodded her head once or twice, very gently and slowly, as if to mark some judgement forming in her mind. At length, in tones from which all colour seemed to have been drained save the soft indeterminate greys as of muted strings, ‘I wonder that you will still be painting,’ she said: ‘you, that are so much in love with the pathetic transitoriness of mortal things: you, that would smite his neck who should rob you of that melancholy sweet debauchery of your mind by fixing your marsh-fires in the sphere and making immortal for you your ephemeral treasures. And yet you will spend all your invention and all your skill, day after day, in wresting out of paint and canvas a counterfeit, frail, and scrappy immortality for something you love to look on, but, by your own confession, would love less did you not fear to lose it.’

‘If you would be answered in philosophy, madam,’ said the Duke, ‘ask old Vandermast, not me.’

‘I have asked him. He can answer nothing to the purpose.’

‘What was his answer?’ said the Duke.

The Lady Fiorinda looked at her picture, again with that lazy, meditative inclining of her head. That imp which the Duke had caught and bottled in paint awhile ago curled in the corner of her mouth. ‘O,’ said she, ‘I do not traffic in outworn answers. Ask him, if you would know.’

‘I will give your ladyship the answer I gave before,’ said that old man, who had sat motionless, serene and unperturbed, darting his bright and eager glance from painter to sitter and to painter again, and smiling as if with the aftertaste of ancient wine. ‘You do marvel that his grace will still consume himself with striving to fix in art, in a seeming changelessness, those self-same appearances which in nature he prizeth by reason of their every mutability and subjection to change and death. Herein your ladyship, grounding yourself at first unassailably upon most predicamental and categoric arguments in celarent, next propounded me a syllogism in barbara, the major premiss whereof, being well and exactly seen, surveyed, overlooked, reviewed, and recognized, was by my demonstrations at large convicted in fallacy of simple conversion and not per accidens; whereupon, countering in bramantip, I did in conclusion confute you in bokardo; showing, in brief, that here is no marvel; since ’tis women’s minds alone are ruled by clear reason: men’s are fickle and elusive as the jack-o’-lanterns they pursue.’