Полная версия:

The Complete Elenium Trilogy: The Diamond Throne, The Ruby Knight, The Sapphire Rose

DAVID EDDINGS

The Elenium Trilogy

The Diamond Throne

The Ruby Knight

The Sapphire Rose

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

The Diamond Throne

First published in Great Britain by Grafton 1989

Previously published in paperback by Grafton 1990

and by HarperCollins Science Fiction & Fantasy 1993, 1995, 2005.

Copyright © David Eddings 1989

Cover Layout Design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

The Ruby Knight

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1990

Previously published in paperback by Grafton 1991

Copyright © David Eddings 1990

Cover Layout Design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

The Sapphire Rose

First published in Great Britain by Grafton 1991

Previously published in paperback by Grafton 1992,

and by HarperCollins Science Fiction & Fantasy 1993.

Copyright © David Eddings 1991

Cover Layout Design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

David Eddings asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBNs:

The Diamond Throne: 9780007578979

The Ruby Knight: 9780007578986

The Sapphire Rose: 9780007578993

Bundle Edition (Containing The Diamond Throne, The Ruby Knight, and The Sapphire Rose) © April 2015 ISBN: 9780008118341

Version: 2015-02-06

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

The Diamond Throne

The Ruby Knight

The Sapphire Rose

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by David Eddings

About the Publisher

DAVID EDDINGS

The Diamond Throne

The Elenium

BOOK ONE

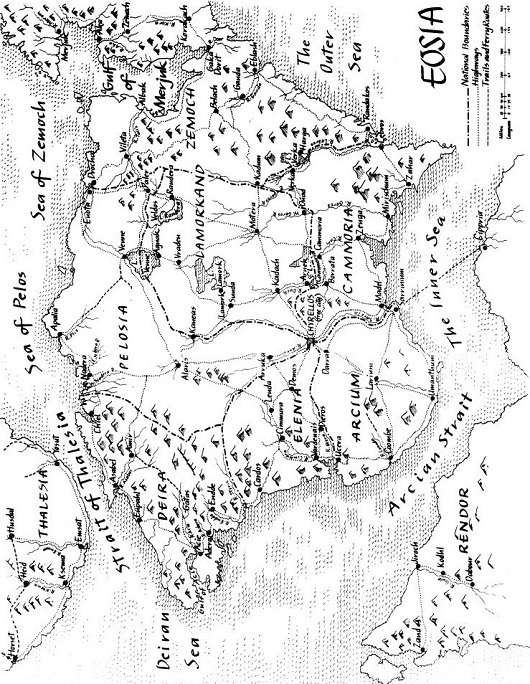

Map

Dedication

For Eleanor and for Ralph,

For courage and for faith.

Trust me.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Map

Dedication

Prologue

Part One: Cimmura

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Part Two: Chyrellos

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Part Three: Dabour

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Prologue

Ghwerig and the Bhelliom – From the Legends of the Troll-Gods

At the dawn of time, long before the ancestors of Styricum slouched, fur-clad and club-wielding, out of the mountains and forests of Zemoch onto the plains of central Eosia, there dwelt in a deep cavern lying beneath the perpetual snows of northern Thalesia a dwarfed and misshapen Troll named Ghwerig. Now, Ghwerig was an outcast by reason of his ugliness and his over-whelming greed, and he laboured alone in the depths of the earth, seeking gold and precious gems that he might add to the treasure-hoard which he jealously guarded. Finally there came a day when he broke into a deep gallery far beneath the frozen surface of the earth and beheld by the light of his flickering torch a deep blue gemstone, larger than his fist, embedded in the wall. Trembling with excitement in all his gnarled and twisted limbs, he squatted on the floor of that passage and gazed with longing at the huge jewel, knowing that its value exceeded that of the entire hoard which he had laboured for centuries to acquire. Then he began with great care to cut away the surrounding stone, chip by chip, so that he might lift the precious gem from the spot where it had rested since the world began. And as more and more it emerged from the rock, he perceived that it had a peculiar shape, and an idea came to him. Could he but remove it intact, he might by careful carving and polishing enhance that shape and thus increase the value of the gem a thousand-fold.

When at last he gently took the jewel from its rocky bed, he carried it straightaway to the cave wherein lay his workshop and his treasure-hoard. Indifferently, he shattered a diamond of incalculable worth and fashioned from its fragments tools with which he might carve and shape the gem which he had found.

For decades, by the light of smoky torches, Ghwerig patiently carved and polished, muttering all the while the spells and incantations which would infuse this priceless gem with all the power for good or ill of the Troll-Gods. When at last the carving was done, the gem was in the shape of a rose of deepest sapphire blue. And he named it Bhelliom, the flower-gem, and he believed that by its might all things might be possible for him.

But though Bhelliom was filled with all the power of the Troll-Gods, it would not yield up that power unto its misshapen and ugly owner, and Ghwerig pounded his fists in rage upon the stone floor of his cavern. He consulted with his Gods and made offerings to them of heavy gold and bright silver, and his Gods revealed to him that there must be a key to unlock the power of Bhelliom, lest its might be unleashed by the whim of any who came upon it. Then the Troll-Gods told Ghwerig what he must do to gain mastery over the gem which he had wrought. Taking the shards which had fallen unnoticed in the dust about his feet as he had laboured to shape the sapphire rose, he fashioned a pair of rings. Of finest gold were the rings, and each was mounted with a polished oval fragment of Bhelliom itself. When it was done, he placed the rings one on each of his hands and then lifted the sapphire rose. The deep, glowing blue of the stones mounted in his rings fled back into Bhelliom itself, and the jewels that adorned his twisted hands were now as pale as diamond. And as he held the flower-gem, he felt the surge of its power, and he rejoiced in the knowledge that the jewel he had wrought had consented to yield to him.

As the uncounted centuries rolled by, great were the wonders Ghwerig wrought by the power of Bhelliom. But the Styrics came at last into the land of the Trolls. When the Elder Gods of Styricum learned of Bhelliom, each in his heart coveted it by reason of its power. But Ghwerig was cunning and he sealed up the entrances to his cavern with enchantments to repel their efforts to wrest Bhelliom from him.

Now at a certain time, the Younger Gods of Styricum took counsel with each other, for they were disquieted about the power which Bhelliom would confer upon whichever God came to possess it, and they concluded that such might should not be unloosed in the earth. They resolved then to render the stone powerless. Of their number they selected the nimble Goddess Aphrael for the task. Then Aphrael journeyed to the north, and, by reason of her slight form, she was able to wriggle her way through a crevice so small that Ghwerig had neglected to seal it. Once she was within the cavern, Aphrael lifted her voice in song. So sweetly she sang that Ghwerig was all bemused by her melody, and he felt no alarm at her presence. So it was that Aphrael lulled him. When, with dreamy smile, the Troll-Dwarf closed his eyes, she tugged the ring from off his right hand and replaced it with a ring set with a common diamond. Ghwerig started up when he felt the tug; but when he looked at his hand, a ring still encircled his finger, and he sat him down again and took his ease, delighting in the song of the Goddess. When once again, in sweet reverie, his eyes dropped shut, the nimble Aphrael tugged the ring from off his left hand, replacing it with yet another ring mounted with yet another diamond. Again Ghwerig started to his feet and looked with alarm at his left hand, but he was reassured by the presence there of a ring which looked for all the world like one of the pair which he had fashioned from the shards of the flower-gem. Aphrael continued to sing for him until at last he lapsed into deep slumber. Then the Goddess stole away on silent feet, bearing with her the rings which were the keys to the power of Bhelliom.

Now, upon a later day, Ghwerig lifted Bhelliom from the crystal case wherein it lay that he might perform a task by its power, but Bhelliom would not yield to him, for he no longer possessed the rings which were the keys to its power. The rage of Ghwerig was beyond measure, and he went up and down in the land seeking the Goddess Aphrael that he might wrest his rings from her, but he found her not, though for centuries he searched.

Thus it was for as long as Styricum held sway over the mountains and plains of Eosia. But there came a time when the Elenes rode out of the east and intruded themselves into this place. After centuries of random wandering to and fro in the land, some of their number came at last into far northern Thalesia and dispossessed the Styrics and their Gods. And when the Elenes heard of Ghwerig and his Bhelliom, they sought the entrances to the Troll-Dwarf’s cavern throughout the hills and valleys of Thalesia, all hot with their lust to find and own the fabled gem by reason of its incalculable worth, for they knew not of the power locked in its azure petals.

It fell at last to Adian of Thalesia, mightiest and most crafty of the heroes of antiquity, to solve the riddle. At peril of his soul, he took counsel with the Troll-Gods and made offering to them, and they relented and told him that Ghwerig went abroad in the land at certain times in search of the Goddess Aphrael of Styricum that he might reclaim a pair of rings which she had stolen from him, but of the true meaning of those rings they told him not. And Adian journeyed to the far north and there he awaited each twilight for a half-dozen years the appearance of Ghwerig.

When at last the Troll-Dwarf appeared, Adian went up to him in a dissembling guise and told him that he knew where Aphrael might be found and that he would reveal her location for a helmet full of fine yellow gold. Ghwerig was deceived and straightaway led Adian to the hidden mouth of his cavern and he took the hero’s helm and went into his treasure chamber and filled it to overflowing with fine gold. Then he emerged again, sealing the entrance to his cavern behind him. And he gave Adian the gold, and Adian deceived him again, saying that Aphrael might be found in the district of Horset on the western coast of Thalesia. Ghwerig hastened to Horset to seek out the Goddess. And once again Adian imperilled his soul and implored the Troll-Gods to break Ghwerig’s enchantments that he might gain entrance to the cavern. The capricious Troll-Gods consented and the enchantments were broken.

As rosy dawn touched the ice fields of the north into flame, Adian emerged from Ghwerig’s cavern with Bhelliom in his grasp. He journeyed straightaway to his capital at Emsat and there he fashioned a crown for himself and surmounted it with Bhelliom.

The chagrin of Ghwerig knew no bounds when he returned empty-handed to his cavern to find that not only had he lost the keys to the power of Bhelliom, but that the flower-gem itself was no longer in his possession. Thereafter he usually lurked by night in the fields and forests about the city of Emsat, seeking to reclaim his treasure, but the descendants of Adian protected it closely and prevented him from approaching it.

Now as it happened, Azash, an Elder God of Styricum, had long yearned in his heart for possession of Bhelliom and of the rings which unlocked its power and he sent forth his hordes out of Zemoch to seize the gems by force of arms. The kings of the west took up arms to join with the Knights of the Church to face the armies of Otha of Zemoch and of his dark Styric God, Azash. And King Sarak of Thalesia took ship with some few of his vassals and sailed south from Emsat, leaving behind the royal command that his earls were to follow when the mobilization of all Thalesia was complete. As it happened, however, King Sarak never reached the great battlefield on the plains of Lamorkand, but fell instead to a Zemoch spear in an unrecorded skirmish near the shores of Lake Venne in Pelosia. A faithful vassal, though mortally wounded, took up his fallen lord’s crown and struggled his way to the marshy eastern shore of the lake. There, hard-pressed and dying, he cast the Thalesian crown into the murky, peat-clouded waters of the lake, even as Ghwerig, who had followed his lost treasure, watched in horror from his place of concealment in a nearby peat bog.

The Zemochs who had slain King Sarak immediately began to probe the brown-stained depths, that they might find the crown and carry it in triumph to Azash, but they were interrupted in their search by a column of Alcione Knights sweeping down out of Deira to join the battle in Lamorkand. The Alciones fell upon the Zemochs and slew them to the last man. The faithful vassal of the Thalesian king was given an honourable burial, and the Alciones rode on, all unaware that the fabled crown of Thalesia lay beneath the turbid waters of Lake Venne.

It is sometimes rumoured in Pelosia, however, that on moonless nights the shadowy form of the immortal Troll-Dwarf haunts the marshy shore. Since, by reason of his malformed limbs, Ghwerig dares not enter the dark waters of the lake to probe its depths, he must creep along the marge, alternately crying out his longing to Bhelliom and dancing in howling frustration that it will not respond to him.

Chapter 1

It was raining. A soft, silvery drizzle sifted down out of the night sky and wreathed around the blocky watch-towers of the city of Cimmura, hissing in the torches on each side of the broad gate and making the stones of the road leading up to the city shiny and black. A lone rider approached the city. He was wrapped in a dark, heavy traveller’s cloak and rode a tall, shaggy roan horse with a long nose and flat, vicious eyes. The traveller was a big man, a bigness of large, heavy bone and ropy tendon rather than of flesh. His hair was coarse and black, and at some time his nose had been broken. He rode easily, but with the peculiar alertness of the trained warrior.

His name was Sparhawk, a man at least ten years older than he looked, who carried the erosion of his years not so much on his battered face as in a half-dozen or so minor infirmities and discomforts and in the several wide purple scars upon his body which always ached in damp weather. Tonight, however, he felt his age, and he wished only for a warm bed in the obscure inn which was his goal. Sparhawk was coming home at last after a decade of being someone else with a different name in a country where it almost never rained, where the sun was a hammer pounding down on a bleached white anvil of sand and rock and hard-baked clay, where the walls of the buildings were thick and white to ward off the blows of the sun, and where graceful women went to the wells in the silvery light of early morning with large clay vessels balanced on their shoulders and black veils across their faces.

The big roan horse shuddered absently, shaking the rain out of his shaggy coat, and approached the city gate, stopping in the ruddy circle of torchlight before the gatehouse.

An unshaven gate guard in a rust-splotched breastplate and helmet, and with a patched green cloak negligently hanging from one shoulder, came unsteadily out of the gatehouse and stood swaying in Sparhawk’s path. ‘I’ll need your name,’ he said in a voice thick with drink.

Sparhawk gave him a long stare, then opened his cloak to show the heavy silver amulet hanging on a chain about his neck.

The half-drunk gate guard’s eyes widened slightly, and he stepped back a pace. ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘sorry, my Lord. Go ahead.’

Another guard poked his head out of the gatehouse. ‘Who is he, Raf?’ he demanded.

‘A Pandion Knight,’ the first guard replied nervously.

‘What’s his business in Cimmura?’

‘I don’t question the Pandions, Bral,’ the man named Raf answered. He smiled ingratiatingly up at Sparhawk. ‘New man,’ he said apologetically, jerking his thumb back over his shoulder at his comrade. ‘He’ll learn in time, my Lord. Can we serve you in any way?’

‘No,’ Sparhawk replied, ‘thanks all the same. You’d better get in out of the rain, neighbour. You’ll catch cold out here.’ He handed a small coin to the green-cloaked guard and rode on into the city, passing up the narrow, cobbled street beyond the gate with the slow clatter of the big roan’s steel-shod hooves echoing back from the buildings.

The district near the gate was poor, with shabby, rundown houses standing tightly packed beside each other with their upper floors projecting out over the wet, littered street. Crude signs swung creaking on rusty hooks in the night wind, identifying this or that tightly shuttered shop on the street-level floors. A wet, miserable-looking cur slunk across the street with his ratlike tail between his legs. Otherwise, the street was dark and empty.

A torch burned fitfully at an intersection where another street crossed the one upon which Sparhawk rode. A sick young whore, thin and wrapped in a shabby blue cloak, stood hopefully under the torch like a pale, frightened ghost. ‘Would you like a nice time, sir?’ she whined at him. Her eyes were wide and timid, and her face gaunt and hungry.

He stopped, bent in his saddle, and poured a few small coins into her grimy hand. ‘Go home, little sister,’ he told her in a gentle voice. ‘It’s late and wet, and there’ll be no customers tonight.’ Then he straightened and rode on, leaving her to stare in grateful astonishment after him. He turned down a narrow side street clotted with shadow and heard the scurry of feet somewhere in the rainy dark ahead of him. His ears caught a quick, whispered conversation in the deep shadows somewhere to his left.

The roan snorted and laid his ears back.

‘It’s nothing to get excited about,’ Sparhawk told him. The big man’s voice was very soft, almost a husky whisper. It was the kind of voice people turned to hear. Then he spoke more loudly, addressing the pair of footpads lurking in the shadows. ‘I’d like to accommodate you, neighbours,’ he said, ‘but it’s late, and I’m not in the mood for casual entertainment. Why don’t you go rob some drunk young nobleman instead, and live to steal another day?’ To emphasize his words, he threw back his damp cloak to reveal the leather-bound hilt of the plain broadsword belted at his side.

There was a quick, startled silence in the dark street, followed by the rapid patter of fleeing feet.

The big roan snorted derisively.

‘My sentiments exactly.’ Sparhawk agreed, pulling his cloak back around him. ‘Shall we proceed?’

They entered a large square surrounded by hissing torches where most of the brightly coloured canvas booths had their fronts rolled down. A few forlornly hopeful enthusiasts remained open for business, stridently bawling their wares to indifferent passers-by hurrying home on a late, rainy evening. Sparhawk reined in his horse as a group of rowdy young nobles lurched unsteadily from the door of a seedy tavern, shouting drunkenly to each other as they crossed the square. He waited calmly until they vanished into a side street and then looked around, not so much wary as alert.

Had there been but a few more people in the nearly empty square, even Sparhawk’s trained eye might not have noticed Krager. The man was of medium height and he was rumpled and unkempt. His boots were muddy, and his maroon cape carelessly caught at the throat. He slouched across the square, his wet, colourless hair plastered down on his narrow skull and his watery eyes blinking nearsightedly as he peered about in the rain. Sparhawk drew in his breath sharply. He hadn’t seen Krager since that night in Cippria, almost ten years ago, and the man had aged considerably. His face was greyer and more pouchy-looking, but there could be no question that it was Krager.

Since quick movements attracted the eye, Sparhawk’s reaction was studied. He dismounted slowly and led his big horse to a green canvas food vendor’s stall, keeping the animal between himself and the nearsighted man in the maroon cape. ‘Good evening, neighbour,’ he said to the brown-clad food vendor in his deadly quiet voice. ‘I have some business to attend to. I’ll pay you if you’ll watch my horse.’

The unshaven vendor’s eyes came quickly alight.

‘Don’t even think it,’ Sparhawk warned. ‘The horse won’t follow you, no matter what you do – but I will, and you wouldn’t like that at all. Just take the pay and forget about trying to steal the horse.’

The vendor looked at the big man’s bleak face, swallowed hard, and made a jerky attempt at a bow. ‘Whatever you say, my Lord,’ he agreed quickly, his words tumbling over each other. ‘I vow to you that your noble mount will be safe with me.’

‘Noble what?’

‘Noble mount – your horse.’

‘Oh, I see. I’d appreciate that.’

‘Can I do anything else for you, my Lord?’

Sparhawk looked across the square at Krager’s back. ‘Do you by chance happen to have a bit of wire handy – about so long?’ He measured out perhaps three feet with his hands.