Полная версия:

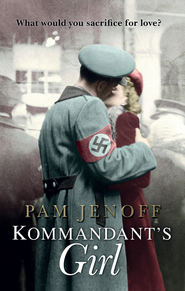

Kommandant's Girl

Kommandant’s Girl

Pam Jenoff

To my family

.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For several years after my return to the United States in 1998, I had wanted to write a novel that captured the experiences in Poland, and particularly with the Jewish community there, that had affected me so profoundly. I was captivated for some time by the vision of a young woman nervously guiding a child across Krakow’s market square during the Nazi occupation. But it was not until early 2002, when I had the good fortune to ride a train from Washington, DC to Philadelphia with an elderly couple who were both Holocaust survivors, that I learned for the first time the extraordinary story of the Krakow resistance. And with that historical foundation, Kommandant’s Girl was born.

There are so many people who have walked this path with me from concept to finished novel. I am eternally grateful to my family, friends and colleagues, including my mother and father, my brother Jay (yes, you can read it now), Phillip, Joanne, Stephanie, Barb and others too numerous to mention for their endless interest, patience and love. I would also like to thank my writing instructor, Janet Benton, and the other writers who have offered selfless guidance, fellowship and support every step of the way.

This book would not have been possible without the relentless efforts of my wonderful agent, Scott Hoffman of Folio Literary Management, who recognised the potential in this book before anyone else, worked tirelessly to refine it, and persevered long after most others would have quit. I would also like to salute my brilliant editor, Susan Pezzack, for her many insights in bringing this work to life and for making a dream come true.

Finally, I have come to realise through the writing of this book that the term “historical fiction” is somewhat of an oxymoron. While creating imaginary characters and events, I have endeavoured to remain true to the spirit of those who lived and died during World War II and the Holocaust, and to realistically depict the full range of human strengths, frailties and emotions brought out by this tragic and remarkable era. To this end, I would like to express my boundless admiration for the Jewish communities of Poland, and all of Central and Eastern Europe, past, present and future: your courageous struggle is an inspiration to us all.

CHAPTER 1

As we cut across the wide span of the market square, past the pigeons gathered around fetid puddles, I eye the sky warily and tighten my grip on Lukasz’s hand, willing him to walk faster. But the child licks his ice-cream cone, oblivious to the darkening sky, a drop hanging from his blond curls. Thank God for his blond curls. A sharp March wind gusts across the square, and I fight the urge to let go of his hand and draw my threadbare coat closer around me.

We pass through the high center arch of the Sukennice, the massive yellow mercantile hall that bisects the square. It is still several blocks to Nowy Kleparz, the outdoor market on the far northern edge of Kraków’s city center, and already I can feel Lukasz’s gait slowing, his tiny, thin-soled shoes scuffing harder against the cobblestones with every step. I consider carrying him, but he is three years old and growing heavier by the day. Well fed, I might have managed it, but now I know that I would make it a few meters at most. If only he would go faster. “Szybko, kochana,” I plead with him under my breath. “Chocz!” His steps seem to lighten as we wind our way through the flower vendors peddling their wares in the shadow of the Mariacki Cathedral spires.

Moments later, we reach the far side of the square and I feel a familiar rumble under my feet. I pause. I have not been on a trolley in almost a year. I imagine lifting Lukasz onto the streetcar and sinking into a seat, watching the buildings and people walking below as we pass. We could be at the market in minutes. Then I stop, shake my head inwardly. The ink on our new papers is barely dry, and the wonder on Lukasz’s face at his first trolley ride would surely arouse suspicion. I cannot trade our safety for convenience. We press onward.

Though I try to remind myself to keep my head low and avoid eye contact with the shoppers who line the streets this midweek morning, I cannot help but drink it all in. It has been more than a year since I was last in the city center. I inhale deeply. The air, damp from the last bits of melting snow, is perfumed with the smell of roasting chestnuts from the corner kiosk. Then the trumpeter in the cathedral tower begins to play the hejnal, the brief melody he sends across the square every hour on the hour to commemorate the Tartar invasion of Kraków centuries earlier. I resist the urge to turn back toward the sound, which greets me like an old friend.

As we approach the end of Florianska Street, Lukasz suddenly freezes, tightening his grip on my hand. I look down. He has dropped the last bit of his precious ice-cream cone on the pavement but does not seem to notice. His face, already pale from months of hiding indoors, has turned gray. “What is it?” I whisper, crouching beside him, but he does not respond. I follow his gaze to where it is riveted. Ten meters ahead, by the arched entrance to the medieval Florian Gate, stand two Nazis carrying machine guns. Lukasz shudders. “There, there, kochana. It’s okay.” I put my arms around his shoulders, but there is nothing I can do to soothe him. His eyes dart back and forth, and his mouth moves without sound. “Come.” I lift him up and he buries his head in my neck. I look around for a side street to take, but there is none and turning around might attract attention. With a furtive glance to make sure no one is watching, I push the remnants of the ice-cream cone toward the gutter with my foot and proceed past the Nazis, who do not seem to notice us. A few minutes later, when I feel the child breathing calmly again, I set him down.

Soon we approach the Nowy Kleparz market. It is hard to contain my excitement at being out again, walking and shopping like a normal person. As we navigate the narrow walkways between the stalls, I hear people complaining. The cabbage is pale and wilted, the bread hard and dry; the meat, what there is of it, is from an unidentifiable source and already giving off a curious odor. To the townspeople and villagers, still accustomed to the prewar bounty of the Polish countryside, the food is an abomination. To me, it is paradise. My stomach tightens.

“Two loaves,” I say to the baker, keeping my head low as I pass him my ration cards. A curious look crosses his face. It is your imagination, I tell myself. Stay calm. To a stranger, I know, I look like any other Pole. My coloring is fair, my accent flawless, my dress purposefully nondescript. Krysia chose this market in a working-class neighborhood on the northern edge of town deliberately, knowing that none of my former acquain-tances from the city would shop here. It is critical that no one recognize me.

I pass from stall to stall, reciting the groceries we need in my head: flour, some eggs, a chicken, if there is one to be had. I have never made lists, a fact that serves me well now that paper is so dear. The shopkeepers are kind, but businesslike. Six months into the war, food is in short supply; there is no generous cut of cheese for a smile, no sweet biscuit for the child with the large blue eyes. Soon I have used all of our ration cards, yet the basket remains half empty. We begin the long walk home.

Still feeling the chill from the wind on the market square, I lead Lukasz through side streets on our way back across town. A few minutes later, we turn onto Grodzka Street, a wide thoroughfare lined with elegant shops and houses. I hesitate. I had not meant to come here. My chest tightens, making it hard to breathe. Easy, I tell myself, you can do this. It is just another street. I walk a few meters farther, then stop. I am standing before a pale yellow house with a white door and wooden flower boxes in the windows. My eyes travel upward to the second floor. A lump forms in my throat, making it difficult to swallow. Don’t, I think, but it is too late. This was Jacob’s house. Our house.

I met Jacob eighteen months ago while I was working as a clerk in the university library. It was a Friday afternoon, I remember, because I was rushing to update the book catalog and get home in time for Shabbes. “Excuse me,” a deep voice said. I looked up from my work, annoyed at the interruption. The speaker was of medium height and wore a small yarmulke and closely trimmed beard and mustache. His hair was brown with flecks of red. “Can you recommend a good book?”

“A good book?” I was caught off guard as much by the swimming darkness of his eyes as by the generic nature of his request.

“Yes, I would like something light to read over the weekend to take my mind off my studies. Perhaps the Iliad …?”

I could not help laughing. “You consider Homer light reading?”

“Relative to physics texts, yes.” The corners of his eyes crinkled. I led him to the literature section, where he settled upon a volume of Shakespeare’s comedies. Our knuckles brushed as I handed him the book, sending a chill down my spine. I checked out the book to him, but still he lingered. I learned that his name was Jacob and that he was twenty, two years my senior.

After that, he came to visit me daily. I quickly learned that even though he was a science major, his real passion was politics and that he was involved with many activist groups. He wrote pieces, published in student and local newspapers, that were critical not only of the Polish government, but of what he called “Germany’s unfettered dominance” over its neighbors. I worried that it was dangerous to be so outspoken. While the Jews of my neighborhood argued heatedly on their front stoops, outside the synagogues and in the stores about current affairs and everything else, I was raised to believe that it was safer to keep one’s voice low when dealing with the outside world. But Jacob, the son of prominent sociologist Maximillian Bau, had no such concerns, and as I listened to him speak, watched his eyes burn and his hands fly, I forgot to be afraid.

I was amazed that a student from a wealthy, secular family would be interested in me, the daughter of a poor Orthodox baker, but if he noticed the difference in our backgrounds, it did not seem to matter. We began spending our Sunday afternoons together, talking and strolling along the Wisla River. “I should be getting home,” I remarked one Sunday afternoon in April as the sky grew dusky. Jacob and I had been walking along the river path where it wound around the base of Wawel Castle, talking so intensely I had lost track of time. “My parents will be wondering where I am.”

“Yes, I should meet them soon,” he replied matter-of-factly. I stopped in my tracks. “That’s what one does, isn’t it, when one wants to ask permission to court?” I was too surprised to answer. Though Jacob and I had spent much time together these recent months and I knew he enjoyed my company, I somehow never thought that he would seek permission to see me formally. He reached down and took my chin in his gloved fingers. Softly, he pressed his lips down on mine for the first time. Our mouths lingered together, lips slightly parted. The ground seemed to slide sideways, and I felt so dizzy I was afraid that I might faint.

Thinking now of Jacob’s kiss, I feel my legs grow warm. Stop it, I tell myself, but it is no use. It has been nearly six months since I have seen my husband, been touched by him. My whole body aches with longing.

A sharp clicking noise jars me from my thoughts. My vision clears and I find myself still standing in front of the yellow house, staring upward. The front door opens and an older, well-dressed woman steps out. Noticing me and Lukasz, she hesitates. I can tell she is wondering who we are, why we have stopped in front of her house. Then she turns from us dismissively, locks the door and proceeds down the steps. This is her home now. Enough, I tell myself sharply. I cannot afford to do anything that will draw attention. I shake my head, trying to clear the image of Jacob from my mind.

“Come, Lukasz,” I say aloud, tugging gently on the child’s hand. We continue walking and soon cross the Planty, the broad swath of parkland that rings the city center. The trees are revealing the most premature of buds, which will surely be cut down by a late frost. Lukasz tightens his grip on my hand, staring wide-eyed at the few squirrels that play among the bushes as though it is already spring. As we push onward, I feel the city skyline receding behind us. Five minutes later we reach the Aleje, the wide boulevard that, if taken to the left, leads south across the river. I stop and look toward the bridge. Just on the other side, a half kilometer south, lies the ghetto. I start to turn in that direction, thinking of my parents. Perhaps if I go to the wall, I can see them, find a way to slip them some of the food I have just purchased. Krysia would not mind. Then I stop—I cannot risk it, not in broad daylight, not with the child. I feel shame at my stomach, which no longer twists with hunger, and at my freedom, at crossing the street as though the occupation and the war do not exist.

Half an hour later, Lukasz and I reach Chelmska, the rural neighborhood we have come to call home. My feet are sore from walking along the uneven dirt road and my arms ache from carrying the groceries, as well as the child, for the last several meters. As we round the corner where the main road divides in two, I inhale deeply; the air has grown colder now, its pureness broken only by an acrid hint of smoke from a farmer burning piles of dead winter brush. I can see the fires smoldering across the sloping farmland to my right, their thick smoke fanning out over the fields that roll like a gentle green lake into the horizon.

We turn left onto the road dotted with farmhouses that, if taken farther, winds upward into the tree-covered hills of Las Wolski. About fifty yards up the road stands Krysia’s house, a dark wood, three-story chalet, nestled among the pine trees. A plume of smoke rises from the chimney to greet us. I set the child down and he runs ahead. Hearing his footsteps, Krysia appears from behind the house and walks to the front gate. With her silver hair piled high on her head, she looks as though she is attending the opera, except that her hands are clad in cracked leather gardening gloves, rather than silk or lace. The hem of her working dress, nicer than anything I could ever hope to own, is caked with dirt. At the sight of Lukasz, her lineless face folds into a smile. She breaks her perfect posture to stoop and lift him.

“Did everything go all right?” Krysia asks as I approach, still bouncing Lukasz on her hip and studying his face. She does not look at me. I am not offended by her preoccupation with the child. In the time he has been with us, he has yet to smile or speak, a fact that is a source of constant worry for both of us.

“More or less.”

“Oh?” Her head snaps up. “What happened?”

I hesitate, not wanting to speak in front of the child. “We saw some, um, Germans.” I tilt my head in Lukasz’s direction. “And it was upsetting. But they didn’t notice us.”

“Good. Were you able to get everything at market?”

I shake my head. “Some things.” I lift the basket slightly. “Not as much as I hoped, though.”

“It’s no matter, we’ll manage. I was just turning over the ground in the garden so that we can seed next month.” Wordlessly, I follow Krysia into the house, amazed as ever at her grace and strength. There is a sense of purpose in the way she shifts her weight as she walks that reminds me of my husband.

Upstairs, Krysia takes the basket from me and begins to unpack the groceries. I wander into the parlor. After two weeks of living here, I am still awestruck by the plush furniture, the beautiful artwork that adorns every wall. I walk past the grand piano to the fireplace. On the mantel sit three framed photographs. One is of Marcin, Krysia’s deceased husband, seated with his cello in front of him, wearing a tuxedo. Another is of Jacob as a child playing by a lake. I lift the third picture. It is a photograph of Jacob and me, taken on our wedding day. We are standing on the steps in front of the Baus’ house on Grodzka Street, Jacob in a dark suit, me in the ankle-length white linen wedding dress that had been worn by my mother and grandmother before me. Though we were supposed to be looking at the camera, our heads are tilted toward each other, my lips parted with laughter at a joke he had just whispered to me.

Originally, we had intended to wait to marry until Jacob graduated the following year. But by late July 1939, Germany had swallowed the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia, and the other countries of Western Europe had done nothing to stop him. Hitler stood poised on the Polish border, ready to pounce. We had heard stories of the Nazis’ abysmal treatment of the Jews in Germany and Austria. If the Nazis came into Poland, who knew what our lives would be like? Better, we decided, to get married right away and face the uncertainties of the future together.

Jacob proposed on a humid afternoon during one of our Sunday walks by the river. “Emma …” He stopped and turned to me, then dropped to one knee. I was not entirely surprised. Jacob had walked to synagogue with my father the previous morning, and I could tell from the pensive way my father looked at me as they returned to the apartment afterward that they had not been discussing politics or religion, but rather our future together. Still, my eyes watered. “Times are uncertain,” Jacob began. Inwardly, I could not help but laugh. Only Jacob could turn a proposal into a political speech. “But I know that whatever is coming, I want to face it with you. Will you do me the honor of becoming my wife?”

“Yes,” I whispered as he slipped a silver ring with a tiny diamond onto my left hand. He rose and kissed me, longer and harder than ever before.

We wed a few weeks later under a canopy in the Baus’ elegant parlor, with only our immediate families in attendance. After the wedding, we moved my few belongings to the spare room in the Baus’ home that Jacob and I were to share. Professor and Mrs. Bau departed shortly after we returned for a teaching sabbatical in Geneva, leaving Jacob and me on our own. Having been raised in a tiny, three-room apartment, I was unaccustomed to living in such splendor. The high ceilings and polished wood floors seemed better suited to a museum. At first, I felt awkward, like a perennial guest in the enormous house, but I soon came to love living in a grand home filled with music, art and books. Jacob and I would lie awake at night and whisper dreams of the following year after his graduation when we would be able to buy a home of our own.

One Friday afternoon about three weeks after the wedding, I decided to walk down to the Jewish quarter, Kazimierz, and pick up some challah bread from my parents’ bakery for dinner. When I arrived at the shop, it was crowded with customers rushing to get ready for Shabbes so I stepped behind the counter to help my harried father fill the orders. I had just handed a customer her change when the door to the shop burst open and a young boy ran in. “The Germans have attacked!” he exclaimed.

I froze. The shop became instantly silent. Quickly, my father retrieved his radio from the back room, and the customers huddled around the counter to hear the news. The Germans had attacked the harbor of Westerplatte, near the northern city of Gdansk; Poland and Germany were at war. Some of the women started crying. The radio announcer stopped speaking then and the Polish national anthem began to play. Several customers began to sing along. “The Polish army will defend us,” I heard Pan Klopowitz, a wizened veteran of the Great War, say to another customer. But I knew the truth. The Polish army, consisting in large part of soldiers on horseback and on foot, would be no match for German tanks and machine guns. I looked to my father and our eyes met. One of his hands was fingering the edge of his prayer shawl, the other gripping the edge of the countertop, knuckles white. I could tell that he was imagining the worst.

“Go,” my father said to me after the customers had departed hurriedly with their loaves of bread. I did not return to the library but rushed home. Jacob was already at the apartment when I arrived, his face ashen. Wordlessly, he drew me into his embrace.

Within two weeks of the German invasion, the Polish army was overrun. Suddenly the streets of Kraków were filled with tanks and large, square-jawed men in brown uniforms for whom the crowds parted as they passed. I was fired from my job at the library, and a few days later, Jacob was told by the head of his department that Jews were no longer permitted to attend the university. Our world as we had known it seemed to disappear overnight.

I had hoped that, once Jacob had been dismissed from the university, he would be home more often, but instead his political meetings took on a frenetic pace, held in secret now at apartments throughout the city at night. Though he did not say it, I became aware that these meetings were somehow related to opposing the Nazis. I wanted to ask him, beg him, to stop. I was terrified that he might be arrested, or worse. I knew, though, that my concerns would not squelch his passion.

One Tuesday night in late September, I dozed off while waiting for him to come home. Sometime later, I awoke. The clock on our nightstand told me that it was after midnight. He should have been home by now. I leapt from bed. The apartment was still, except for the sound of my bare feet on the hardwood floor. My mind raced. I paced the house like a mad- woman, returning to the window every five minutes to scan the street below.

Sometime after one-thirty, I heard a noise in the kitchen. Jacob had come up the back stairway. His hair and beard, usually so well-kept, were disheveled. A thin line of perspiration covered the area above his upper lip. I threw my arms around him, trembling. Wordlessly, Jacob took my hand and led me into our bedroom. I did not try to speak further as he pushed me down to the mattress and pressed his weight on top of me with an urgency I had never felt before.

“Emma, I have to leave,” he said later that night, as we lay in the dark listening to the rumbling of the trolleys below. The sweat of our lovemaking had dried on my skin in the cool autumn air, leaving me with an inescapable chill.

My stomach tightened. “Because of your work?”

“Yes.”

I knew he was not referring to his former university job. “When?” I asked, my voice trembling.

“Soon … days, I think.” There was an uneasiness in his voice that told me he was not saying all that he knew. He rolled over to press his stomach against my back and curled his knees under mine. “I will leave money in case you need anything.”

I waved my hand in the dark. “I don’t want it.” My eyes teared. Please, I wanted to say. I would have begged if I thought it would have done any good.

“Emma …” He paused. “You should go to your parents.”

“I will.” When you are gone, I thought.

“One other thing …” His warmth pulled away from me and he reached into the drawer of the nightstand. The paper he handed me felt new, the candle-wax seal raised. “Burn this.” It was our kittubah, our Hebrew marriage certificate. In the rush of events, we had not had time to register our marriage with the civil authorities.

I pushed the paper back at him. “Never.”

“You must take off your rings, pretend we were never married. Tell your family to say nothing.” He continued, “It will be dangerous for you if anyone knows you are my wife once I am gone.”

“Dangerous? Jacob, I am a Jew in a country occupied by Nazis. How much more dangerous can it get?”