Полная версия:

The Strangled Queen

The Strangled Queen

Book Two of The Accursed Kings

MAURICE DRUON

Translated from French by Humphrey Hare

‘History is a novel that has been lived’

E. & J. DE GONCOURT

Contents

Title Page

Epigraph

Foreword: George R.R. Martin

The Characters in this Book

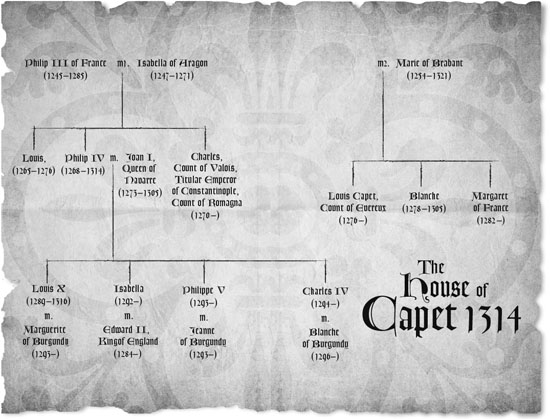

Family Tree

Prologue

Part One: The Dawn of a Reign

1. The Prisoners of Château-Gaillard

2. Robert of Artois

3. Shall She be Queen?

4. Long Live the King!

5. The Princess in Naples

6. The Royal Bed

Part Two: Dog Eats Dog

1. The Hutin’s First Council

2. Marigny Remains Rector-General

3. Charles of Valois

4. Who Rules France?

5. A Castle by the Sea

6. Chasing Cardinals

7. A Pope is Worth an Exoneration

8. A Letter’s Fate

Part Three: The Road to Montfaucon

1. Famine

2. Vincennes

3. A Slaughter of Doves

4. The Night Without a Dawn

5. A Morning of Death

6. The Fall of a Statue

Footnotes

Historical Notes

Author’s Acknowledgements

By Maurice Druon

Copyright

About the Publisher

Foreword

GEORGE R.R. MARTIN

Over the years, more than one reviewer has described my fantasy series, A Song of Ice and Fire, as historical fiction about history that never happened, flavoured with a dash of sorcery and spiced with dragons. I take that as a compliment. I have always regarded historical fiction and fantasy as sisters under the skin, two genres separated at birth. My own series draws on both traditions … and while I undoubtedly drew much of my inspiration from Tolkien, Vance, Howard, and the other fantasists who came before me, A Game of Thrones and its sequels were also influenced by the works of great historical novelists like Thomas B. Costain, Mika Waltari, Howard Pyle … and Maurice Druon, the amazing French writer who gave us the The Accursed Kings, seven splendid novels that chronicle the downfall of the Capetian kings and the beginnings of the Hundred Years War.

Druon’s novels have not been easy to find, especially in English translation (and the seventh and final volume was never translated into English at all). The series has twice been made into a television series in France, and both versions are available on DVD … but only in French, undubbed, and without English subtitles. Very frustrating for English-speaking Druon fans like me.

The Accursed Kings has it all. Iron kings and strangled queens, battles and betrayals, lies and lust, deception, family rivalries, the curse of the Templars, babies switched at birth, she-wolves, sin, and swords, the doom of a great dynasty … and all of it (well, most of it) straight from the pages of history. And believe me, the Starks and the Lannisters have nothing on the Capets and Plantagenets.

Whether you’re a history buff or a fantasy fan, Druon’s epic will keep you turning pages. This was the original game of thrones. If you like A Song of Ice and Fire, you will love The Accursed Kings.

George R.R. Martin

The Characters in this Book

THE KING OF FRANCE AND NAVARRE:

LOUIS X, called The Hutin, son of Philip IV, the Fair, great-grandson of Saint Louis, aged 25.

HIS BROTHERS:

MONSEIGNEUR PHILIPPE, Count of Poitiers, a peer of France, aged 21.

MONSEIGNEUR CHARLES, Count of La Marche, aged 20.

HIS UNCLES:

MONSEIGNEUR CHARLES, Count of Valois, titular Emperor of Constantinople, Count of Romagna, peer of France, aged 44.

MONSEIGNEUR LOUIS, Count of Evreux, aged about 41.

HIS WIFE:

MARGUERITE, daughter of the Duke of Burgundy, granddaughter of Saint Louis, aged 21.

HIS DAUGHTER:

JEANNE OF FRANCE AND NAVARRE, aged 3.

HIS SISTER-IN-LAW:

BLANCHE, wife of Charles of La Marche, daughter of the Count Palatine of Burgundy and of Mahaut, Countess of Artois, aged about 19.

THE ARTOIS BRANCH DESCENDED FROM A BROTHER OF SAINT LOUIS:

ROBERT III OF ARTOIS, Lord of Conches, Count of Beaumont-le-Roger, aged 27.

THE BRANCH OF ANJOU-SICILY DESCENDED FROM ANOTHER BROTHER OF SAINT LOUIS:

MARIE OF HUNGARY, Queen of Naples, widow of Charles II of Naples, mother of the Kings Robert of Naples and Charles of Hungary, aged about 70.

CLÉMENCE OF HUNGARY, her granddaughter, daughter of Charles Martel and sister of Charobert, King of Hungary, aged 22.

THE BROTHERS MARIGNY:

ENGUERRAND, Coadjutor of King Philip the Fair and Rector-General of the kingdom, aged 49.

JEAN, Archbishop of Sens and Paris, aged about 35.

THE LOMBARDS:

SPINELLO TOLOMEI, a Siennese banker living in Paris, Captain-General of the Lombard Companies, aged about 60.

GUCCIO BAGLIONI, his nephew, aged 18.

SIGNOR BOCCACCIO, traveller for the Bardi Company.

THE CRESSAY FAMILY:

DAME ELIABEL, widow of the Squire of Cressay, aged about 40.

PIERRE and JEAN, her sons, aged about 20 and 22.

MARIE, her daughter, aged 16.

AND THESE:

EUDELINE, LOUIS X’s mistress, aged about 32.

HUGUES DE BOUVILLE, First Chamberlain to King Philip the Fair.

ALAIN DE PAREILLES, Captain-General of the Archers.

JACQUES DUÈZE, Bishop of Porto, Cardinal of the Curia, aged 70.

ROBERT BERSUMÉE, Captain of Château-Gaillard, aged 35.

ROBERTO ODERISI, a Neapolitan painter, pupil of Giotto.

All the above are historical names, as are those of the barons, justiciars, chamberlains, members of the Council, chancellors, the Abbot of Saint-Denis and the great officers of the Crown; all these people really existed. The only imaginary names are those of a few extras, of whom no trace can be found, such as Robert of Artois’s servant and the Provost of Montfort-I’Amaury.

Family Tree

Prologue

ON the 29th November 1314, two hours after vespers, twenty-four couriers, all dressed in black and wearing the emblems of France, passed out of the gate of the Château of Fontainebleu at full gallop and disappeared into the forest. The roads were covered with snow; the sky was more sombre than the earth; darkness had fallen, or rather it had remained constant since the evening before.

The twenty-four couriers would have no rest before morning, and would gallop onwards all next day, all the following days, some towards Flanders, some towards Angoumois and Guyenne, some towards Dole in the Comté, some towards Rennes and Nantes, some towards Toulouse, some towards Lyons, Aigues-Mortes and Marseilles, awakening bailiffs, provosts and seneschals, to announce in town and village throughout the kingdom that King Philip IV, called the Fair, was dead.

All along the roads the knell tolled out in dark steeples, a wave of sonorous, sinister sound spreading ever further till it reached all the frontiers of the kingdom.

After twenty-nine years of stern rule, the Iron King was dead of a cerebral haemorrhage at the age of forty-six. It had occurred during an eclipse of the sun, which had spread a deep shadow over the land of France.

Thus, for the third time, the curse laid eight months earlier by the Grand Master of the Templars from the middle of a flaming pyre was fulfilled.fn1

King Philip, stern, haughty, intelligent and secretive, had reigned with such competence and so dominated his period that, upon this evening, it seemed that the heart of the kingdom had ceased to beat.

But nations never die of the death of a man, however great he may have been; their birth and their death derive from other causes.

The name of Philip the Fair would glow down the centuries only by the flicker of the faggots he had lighted beneath his enemies and the glitter of the gold he had seized. It would quickly be forgotten that he had curbed the powerful, maintained peace in so far as it was possible, reformed the law, constructed fortresses that the land might be cultivated in their shelter, united provinces, convoked assemblies of the middle class so that it might speak its mind, and watched unremittingly over the independence of France.

Hardly had his hands grown cold, hardly had the great power of his will become extinguished, than private interest, disappointed ambition, and the thirst for honours and wealth began to proclaim their presence.

Two parties were in opposition, battling mercilessly for power: on the one hand, the clan of the reactionary Barons, at its head the Count of Valois, titular Emperor of Constantinople and brother of Philip the Fair; on the other, the clan of the high administration, at its head Enguerrand de Marigny, first Minister and Coadjutor of the dead king.

A strong king had been required to avoid or hold in balance the conflict which had been incubating for many months. And now the twenty-five-year-old prince, Monseigneur Louis, already King of Navarre, who was succeeding to the throne, seemed ill-endowed for sovereignty; his reputation was that, merely, of a cuckolded husband and whatever could be learned from his melancholy nickname of The Hutin, The Headstrong.

His wife, Marguerite of Burgundy, the eldest of the Princesses of the Tower of Nesle, had been imprisoned for adultery, and her life was, curiously enough, to be a stake in the interplay of the rival factions.

But the cost of faction, as always, was to be the misery of the poor, of those who lacked even the dreams of ambition. Moreover, the winter of 1314–15 was one of famine.

PART ONE

THE DAWN OF A REIGN

1

The Prisoners of Château-Gaillard

BUILT SIX HUNDRED FEET up upon a chalky spur above the town of Petit-Andelys, Château-Gaillard both commanded and dominated the whole of Upper Normandy.

At this point the river Seine describes a large loop through rich pastures; Château-Gaillard held watch and ward above the river for twenty miles up and down stream.

Today the ruins of this formidable citadel can still startle the eye and defy the imagination. With the Krak des Chevaliers in the Lebanon, and the towers of Roumeli-Hissar on the Bosphorus, it remains one of the most imposing relics of the military architecture of the Middle Ages.

Before these monuments, constructed to make conquest good or threaten empire, the imagination is obsessed by the men, separated from us by no more than fifteen or twenty generations, who built them, used them, lived in them, and sacked them.

At the period of this story, Château-Gaillard was no more than a hundred and twenty years old. Richard Cœur-de-Lion had built it in two years, in defiance of treaties, to defy the King of France. Seeing it finished, standing high upon its cliff, its freshly hewn stone white upon its two curtain walls, its outer works well advanced, its portcullises, battlements, thirteen towers, and huge, two-storied keep, he had cried: ‘Oh, what a gallant [gaillard] castle!’

Ten years later Philip Augustus took it from him, together with the whole land of Normandy.

Since then Château-Gaillard had no longer served a military purpose and had become a royal prison.

Important state criminals were confined there, prisoners whom the King wished to preserve alive but incarcerate for life. Whoever crossed the drawbridge of Château-Gaillard had little chance of ever re-entering the world.

By day crows croaked upon its roofs; by night wolves howled beneath its walls. The only exercise permitted the prisoners was to walk to the chapel to hear Mass and return to their tower to await death.

Upon this last morning of November 1314, Château-Gaillard, its ramparts and its garrison of archers were employed merely in guarding two women, one of twenty-one years of age, the other of eighteen, Marguerite and Blanche of Burgundy, two cousins, both married to sons of Philip the Fair, convicted of adultery with two young equerries and condemned to life-imprisonment as the result of the most resounding scandal that had ever burst upon the Court of France.1 fn2

The chapel was inside the inner curtain wall. It was built against the natural rock; its interior was dark and cold; the walls had few openings and were unadorned.

Before the choir were placed three seats only: two on the left for the Princesses, one on the right for the Captain of the Fortress.

At the rear of the chapel the men-at-arms stood in their ranks, manifesting an air of boredom similar to the one they wore when engaged upon the fatigue of foraging.

‘My brothers,’ said the Chaplain, ‘today we must pray with peculiar fervour and solemnity.’

He cleared his throat and hesitated a moment, as if concerned at the importance of what he had to announce.

‘The Lord God has called to himself the soul of our much-beloved King Philip,’ he went on. ‘This is a profound tragedy for the whole kingdom.’

The two Princesses turned towards each other faces shrouded in hoods of coarse brown cloth.

‘May those who have done him injury or wrong repent of it in their hearts,’ continued the Chaplain. ‘May those who had some grievance against him when he was alive, pray for that mercy for him of which every man, great or small, has equal need at his death before the tribunal of our Lord …’

The two Princesses had fallen on their knees, bending their heads to hide their joy. No longer did they feel the cold, no longer the pain and grief; a great surge of hope rose within them; and had the idea of praying to God crossed their minds, it would but have been to thank Him for delivering them from their terrible father-in-law. It was the first good news that had reached them from the outside world in all the seven months of their imprisonment in Château-Gaillard.

The men-at-arms, at the back of the chapel, whispered together, questioning each other in low voices, shuffling their feet, beginning to make too much noise.

‘Shall we be given a silver penny each?’

‘Why, because the King is dead?’

‘It’s usual, at least I’m told so.’

‘No, you’re wrong, not for his death; only, perhaps, for the coronation of the next one.’

‘And what’s the new king going to call himself?’

‘Monsieur Saint Louis was the ninth; obviously this one will call himself Louis X.’

‘Do you think he’ll go to war so that we can move around a bit?’

The Captain of the Fortress turned about and shouted harshly, ‘Silence!’

He too had his worries. The elder of the prisoners was the wife of Monseigneur Louis of Navarre, who was to become king today. ‘So I am now in the position of being gaoler to the Queen of France,’ he thought.

Being goaler to royal personages can never be a situation of much comfort; and Robert Bersumée owed some of the worst moments of his life to these two convicted criminals who had arrived, their heads shaven, towards the end of April, in black-draped wagons, escorted by a hundred archers under the command of Messire Alain de Pareilles. What anxiety and worry he had endured to set against the paltry satisfaction of his vanity! They were two young women, so young that he could not help pitying them despite their sin. They were too beautiful, even beneath their shapeless robes of rough serge, for it to be possible to avoid some emotion at the sight of them day after day for seven months. Supposing they seduced some sergeant of the garrison, supposing they escaped, or one of them hanged herself, or they succumbed to some fatal disease, or again supposing their fortunes revived – for could one ever tell what might not happen in Court affairs? It would be he who was always in the wrong, culpable of being too harsh or too weak, and none of it would help him to promotion. Moreover, like the Chaplain, the prisoners and the men-at-arms themselves, he had no wish to finish his days and his career in a fortress battered by the winds, drenched by the mists, built to accommodate two thousand soldiers and which now held no more than one hundred and fifty, above a valley of the Seine from which war had long ago retreated.

‘The Queen of France’s gaoler,’ the Captain of the Fortress repeated to himself; ‘it needed but that.’

No one was praying; everyone pretended to follow the service while thinking only of himself.

‘Requiem æternam dona eis domine,’ the Chaplain intoned.

He was thinking with fierce jealousy of priests in rich chasubles at that moment singing the same notes beneath the vaults of Notre-Dame. A Dominican in disgrace, who had, upon taking orders, dreamed of being one day Grand Inquisitor, he had ended as a prison chaplain. He wondered whether the change of reign might bring him some renewal of favour.

‘Et lux perpetua luceat eis,’ responded the Captain of the Fortress, envying the lot of Alain de Pareilles, Captain-General of the Royal Archers, who marched at the head of every procession.

‘Requiem æternam … So they won’t even issue us with an extra ration of wine?’ murmured Private Gros-Guillaume to Sergeant Lalaine.

But the two prisoners dared not utter a word; they would have sung too loudly in their joy.

Certainly, upon that day, in many of the churches of France, there were people who sincerely mourned the death of King Philip, without perhaps being able to explain precisely the reasons for their emotion; it was simply because he was the King under whose rule they had lived, and his passing marked the passing of the years. But no such thoughts were to be found within the prison walls.

When Mass was over, Marguerite of Burgundy was the first to approach the Captain of the Fortress.

‘Messire Bersumée,’ she said, looking him straight in the eye, ‘I wish to talk with you upon matters of importance which also concern yourself.’

The Captain of the Fortress was always embarrassed when Marguerite of Burgundy looked directly at him and on this occasion he felt even more uneasy than usual.

He lowered his eyes.

‘I shall come to speak with you, Madam,’ he replied, ‘as soon as I have done my rounds and changed the guard.’

Then he ordered Sergeant Lalaine to accompany the Princesses, recommending him in a low voice to behave with particular correctness.

The tower in which Marguerite and Blanche were confined had but three high, identical, circular rooms, placed one above the other, each with hearth and overmantel and, for ceiling, an eight-arched vault; these rooms were connected by a spiral staircase constructed in the thickness of the wall. The ground-floor room was permanently occupied by a detachment of their guard – a guard which caused Captain Bersumée such anxiety that he had it relieved every six hours in continuous fear that it might be suborned, seduced or outwitted. Marguerite lived in the first-floor room and Blanche on the second floor. At night the two Princesses were separated by a heavy door closed halfway up the staircase; by day they were allowed to communicate with each other.

When the sergeant had accompanied them back, they waited till every hinge and lock had creaked into place at the bottom of the stairs.

Then they looked at each other and with a mutual impulse fell into each other’s arms crying. ‘He’s dead, dead.’

They hugged each other, danced, laughed and cried all at once, repeating ceaselessly, ‘He’s dead!’

They tore off their hoods and freed their short hair, the growth of seven months.

Marguerite had little black curls all over her head, Blanche’s hair had grown unequally, in thick locks like handfuls of straw. Blanche ran her hand from her forehead back to her neck and, looking at her cousin, cried, ‘A looking-glass! The first thing I want is a looking-glass! Am I still beautiful, Marguerite?’

She behaved as if she were to be released within the hour and had now no concern but her appearance.

‘If you ask me that, it must be because I look so much older myself,’ said Marguerite.

‘Oh no!’ Blanche cried. ‘You’re as lovely as ever!’

She was sincere; in shared suffering change passes unnoticed. But Marguerite shook her head; she knew very well that it was not true.

And indeed the Princesses had suffered much since the spring: the tragedy of Maubuisson coming upon them in the midst of their happiness; their trial; the appalling death of their lovers, executed in their presence in the Great Square of Pontoise; the obscene shouts of the populace massed on their route; and after that half a year spent in a fortress; the wind howling among the eaves; the stifling heat of summer reflected from the stone; the icy cold suffered since autumn had begun; the black buckwheat gruel that formed their meals; their shirts, rough as though made of hair, and which they were allowed to change but once every two months; the window narrow as a loophole through which, however you placed your head, you could see no more than the helmet of an invisible archer pacing up and down the battlements – these things had so marked Marguerite’s character, and she knew it well, that they must also have left their mark upon her face.

Perhaps Blanche with her eighteen years and curiously volatile character, amounting almost to heedlessness, which permitted her to pass instantaneously from despair to an absurd optimism – Blanche, who could suddenly stop weeping because a bird was singing beyond the wall, and say wonderingly, ‘Marguerite! Do you hear the bird?’ – Blanche, who believed in signs, every kind of sign, and dreamed unceasingly as other women stitch, Blanche, perhaps, if she were freed from prison, might recover the complexion, the manner and the heart of other days; Marguerite, never. There was something broken in her that could never be mended.

Since the beginning of her imprisonment she had never shed so much as a single tear; but neither had she ever had a moment of remorse, of conscience or of regret.

The Chaplain, who confessed her every week, was shocked by her spiritual intransigence.

Not for an instant had Marguerite admitted her own responsibility for her misfortunes; not for an instant had she admitted that, when one is the granddaughter of Saint Louis, the daughter of the Duke of Burgundy, Queen of Navarre and destined to succeed to the most Christian throne of France, to take an equerry for lover, receive him in one’s husband’s house, and load him with gaudy presents, constituted a dangerous game which might cost one both honour and liberty. She felt that she was justified by the fact that she had been married to a prince whom she did not love, and whose nocturnal advances filled her with horror.