Полная версия:

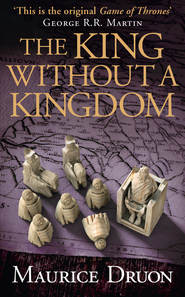

The King Without a Kingdom

Copyright

HarperVoyager an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Copyright © Maurice Druon 1977

This translation copyright © Andrew Simpkin 2014

First published in French as Quand un Roi perd la France

Cover Layout Design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Jacket digital illustration © Patrick Knowles

Jacket photograph © Antiquarian Images (map)

Maurice Druon asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007491377

Ebook Edition © January 2015 ISBN: 9780007492275

Version: 2014-11-29

‘Our longest war, the Hundred Years War, was merely a legal debate, interspersed with occasional bouts of armed warfare’

PAUL CLAUDEL

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Foreword

Author’s Acknowledgements

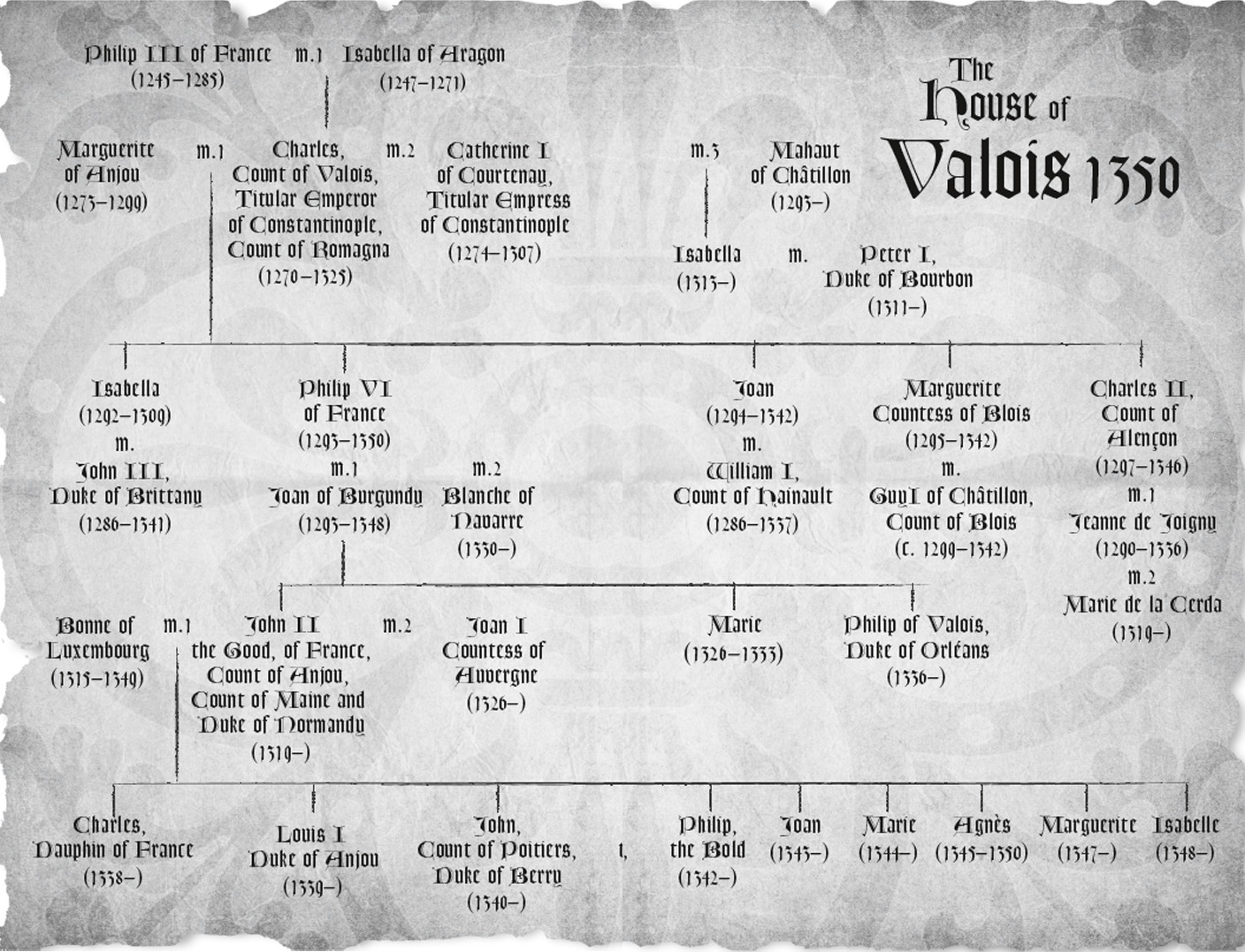

Family Tree

Map

Prologue

Part One: Misfortunes Come From Long Ago

1. The Cardinal of Périgord thinks …

2. The Cardinal of Périgord speaks

3. Death knocks on every door

4. The Cardinal and the Stars

5. The Beginnings of the King they call The Good

6. The Beginnings of the King they call The Bad

7. News from Paris

8. The Treaty of Mantes

9. The Bad in Avignon

10. The Annus Horribilis

11. The Kingdom Cracks

Part Two: The Banquet of Rouen

1. Exemptions and Benefits

2. The Anger of the King

3. To Rouen

4. The Banquet

5. The Arrest

6. The Preparations

7. The Field of Forgiveness

Part Three: The Lost Spring

1. The Hound and the Fox Cub

2. The Nation of England

3. The Pope and the World

Part Four: The Summer of Disaster

1. The Norman Chevauchée

2. The Siege of Breteuil

3. The Homage of Phoebus

4. The Camp of Chartres

5. The Prince of Aquitaine

6. The Cardinal’s Approach

7. The Hand of God

8. The Battalion of the King

9. The Prince’s Supper

Translator’s notes and historical explanations

By Maurice Druon

About the Publisher

Foreword

GEORGE R.R. MARTIN

Over the years, more than one reviewer has described my fantasy series, A Song of Ice and Fire, as historical fiction about history that never happened, flavoured with a dash of sorcery and spiced with dragons. I take that as a compliment. I have always regarded historical fiction and fantasy as sisters under the skin, two genres separated at birth. My own series draws on both traditions … and while I undoubtedly drew much of my inspiration from Tolkien, Vance, Howard, and the other fantasists who came before me, A Game of Thrones and its sequels were also influenced by the works of great historical novelists like Thomas B. Costain, Mika Waltari, Howard Pyle … and Maurice Druon, the amazing French writer who gave us the The Accursed Kings, seven splendid novels that chronicle the downfall of the Capetian kings and the beginnings of the Hundred Years War.

Druon’s novels have not been easy to find, especially in English translation (and the seventh and final volume was never translated into English at all). The series has twice been made into a television series in France, and both versions are available on DVD … but only in French, undubbed, and without English subtitles. Very frustrating for English speaking Druon fans like me.

The Accursed Kings has it all. Iron kings and strangled queens, battles and betrayals, lies and lust, deception, family rivalries, the curse of the Templars, babies switched at birth, she-wolves, sin, and swords, the doom of a great dynasty … and all of it (well, most of it) straight from the pages of history. And believe me, the Starks and the Lannisters have nothing on the Capets and Plantagenets.

Whether you’re a history buff or a fantasy fan, Druon’s epic will keep you turning pages. This was the original game of thrones. If you like A Song of Ice and Fire, you will love The Accursed Kings.

George R.R. Martin

Author’s Acknowledgements

I am most grateful to Jacques Suffel for his assistance in gathering and compiling the documentation for this book. I would also like to express my thanks to the Bibliothèque Nationale as well as to the Archives de France.

Family Tree

Kingdom of France map

Prologue

HISTORY’S TRAGEDIES REVEAL great men: but those tragedies are provoked by the mediocre.

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, France was the most powerful, the most densely populated, the most dynamic, and the richest of the Christian kingdoms, whose interventions were most feared, whose arbitration was heeded and whose protection was sought after. And one could have thought that a French century was about to take hold across Europe.

How, then, did it happen that this same France forty years later came to be crushed on the battlefield by a nation it outnumbered fivefold? Why should its noblemen be split up into factions, its bourgeoisie in revolt, its people overwhelmed by excessive taxation, its provinces lawless and plagued by roving gangs engaged in pillaging and crime, all authority flouted, the currency weakened, trade at a standstill, and poverty and violence rife everywhere? Why this collapse? What caused this reversal of fortune?

It was mediocrity. The mediocrity of just a few kings, their vanity and self-importance, their frivolousness in the conduct of their affairs, their inability to attract talented advisors, their nonchalance, their presumptuousness, their failure to draw up grand designs or even to follow those already conceived.

Nothing great can be accomplished politically, and nothing can last, without the presence of men whose brilliance, character and determination inspire, rally and channel the energies of a people.

Everything falls apart when weak protagonists succeed one another at the head of the State. Unity breaks down when greatness falls away.

France is an idea that embraces history, a wilful idea, which from almost exactly the year one thousand onwards had a ruling family, the House of Capet, that passed on its rule so stubbornly from father to son that being the first-born male child of the oldest branch fast became legitimacy enough to reign.

Luck certainly played its part, as though fate had wanted to favour this burgeoning nation with a sturdy dynasty. From the election of the first Capetian up until the death of Philip the Fair, France had only eleven kings, in three and a quarter centuries, and each one left a male heir.

Oh! These sovereigns were not all blessed with genius. But the incapable or the unfortunate would so often be succeeded immediately by a monarch of great stature, or a great minister would stand in for the faltering prince and govern in his place, it was as if by the grace of God the dynasty persisted.

The fledgling France almost perished in the hands of Philip I, a man of minor vice and major incompetence. Then came the corpulent but indefatigable Louis VI, who found on his accession a country under threat just five leagues from Paris, and left it restored to its former glory, stretching as far as the Pyrenees. The undecided, inconsistent Louis VII engaged the kingdom in disastrous adventures overseas; but the Abbot Suger maintained the cohesion and activity of the country in the name of the monarch.

And France’s luck, repeatedly, was to have between the end of the twelfth and the beginning of the fourteenth centuries three sovereigns of exceptional talent, each one blessed by a long reign – forty-three years, forty-one years, and twenty-nine years respectively on the throne – so that their main designs could be rendered irreversible. Three men of most different natures and virtues, but all three very much in another league compared to any other king.

Philip II Augustus, master craftsman of history, began to build the unity of his native land literally in stone, building around and beyond the royal possessions. Saint Louis, enlightened by devotion, began to establish the unity of law, building upon royal justice. Philip the Fair, superior statesman, began to lay down the unity of the state, building on royal administration. Not one of them was overly worried about pleasing the people, but more concerned with being both active and effective. Each one of them had to swallow the bitter draught of unpopularity. But they were more sorely missed after their death than they had been disparaged, mocked or hated while they were alive. And above all, what they had strived for came to be.

A country, a judicial system, a state: the defining foundations of a nation. Under these three supreme artisans of the idea of France, the country emerged from the age of potentiality. Self-aware, France was establishing itself in the western world as an indisputable, and soon to be pre-eminent, reality.

With twenty-two million inhabitants, its borders well guarded, an army that could be called up quickly, feudal lords kept at heel, constituencies perfectly controlled, roads safe, trade flourishing; what other Christian country could compare itself to France, and which would not be envious of it? The people complained of course, feeling controlled by a hand they considered too firm; later they would moan a good deal more when delivered up to hands too soft or too deranged.

With the death of Philip the Fair, suddenly the idea of France cracked. The long succession of good fortune was broken.

The three sons of the Iron King followed each other on the throne without leaving male descent. We have previously told the story of the dramas the court of France went through as its crown was repeatedly auctioned to the most ambitious bidder.

Four kings committed to the grave in the space of fourteen years; more than enough to fill minds with dismay! France was not used to rushing to Rheims quite so often. It was as if the Capetian family tree had been struck by lightning in its very trunk. And to see the crown slip into the hands of the Valois branch, the troubled branch, would reassure no one. Ostentatious, impulsive, enormously presumptuous princes, all form and no substance, the Valois imagined that all they had to do was smile to make the kingdom happy. Their predecessors mistook themselves for France itself. They mistook France for the idea they had of themselves. After the curse of rapid demise came the curse of mediocrity.

The first of the Valois, Philip VI, called ‘the found king’, in other words the upstart, had a ten-year period during which he might have been able to secure his power base, but then, at the end of this time, his first cousin Edward III of England resolved to open the dynastic feud; he declared himself entitled king of France, which allowed him to rally, in Flanders, Brittany, Saintonge and Aquitaine, all those who had grounds for complaint with the new regime, including leaders of towns and feudal overlords. Faced with a more effective monarch, the Englishman would most probably have continued to dither.

But Philip of Valois was incapable of warding off impending danger and no more capable of defeating it when it came; his fleet was annihilated at the Battle of Sluys because its admiral had been selected for his ignorance of the sea; and the king himself was guilty of letting his cavalry charge trample their own infantry, carnage he saw with his own eyes when roaming through the battlefield the night after the Battle of Crécy.

When Philip the Fair introduced taxes that the people would hold against him, it was in order to build up France’s defences. When Philip of Valois demanded even higher taxes, it was simply to pay the price of his defeats.

Over the last five years of his reign, exchange rates were adjusted one hundred and sixty times; the currency lost three quarters of its value. Foodstuffs, ruthlessly taxed, reached astronomic prices. An unprecedented inflation made the towns increasingly angry.

When misfortune seems to circle on cruel wings above a country, everything gets confused, and any natural disaster, let alone one of the worst in history, adds further insult to the injury of human error.

The plague, the Great Plague, having originated far away in Asia, hit France; no other part of Europe was hit harder. The streets of towns became places where the dying lay, the suburbs open graves. Here a quarter of the population succumbed, there a third perished. Entire villages were wiped out, and all that was left of them were dilapidated houses open to the winds on a wasteland of neglect.

Philip of Valois had a son that the plague, alas, was to spare.

France was to sink yet deeper into distress and ruin; this ultimate descent was to be the work of John II, erroneously called the Good.

This lineage of mediocre monarchs came close to cleaving apart the system that since the Middle Ages had trusted nature to produce within one and the same family the bearer of the sovereign’s power. Are peoples any more likely to win in the lottery of democracy than in the haphazardness of genetics? Crowds, assemblies, even select councils are no less likely to be in error than nature; and anyway, Providence has always been miserly with greatness.

1

The Cardinal of Périgord thinks …

I SHOULD HAVE BEEN pope. How can I fail to think again and again that thrice I held the tiara in my hands; three times! As much for Benedict XII and for Clement VI as for our current pontiff, it is I who decided, as the battle drew to a close, on whose head the tiara was placed. My friend Petrarch calls me pope-maker, not such a great maker, after all, as it was never upon my own head that the tiara would be set. Enfin, it is God’s will. Ah! What a strange thing is a conclave! I believe I am the only cardinal alive to have seen three of them. And maybe I will see a fourth, if Innocent is as ill as he makes out.

What are those rooftops yonder? Yes, I recognize them, Chancelade Abbey, in the Valley of Beauronne. The first time, admittedly, I was too young. Thirty-three, the age of Christ crucified: this fact was being whispered all over Avignon as soon as it was known John XXII (Lord, guard his soul in Your holy light; he was my benefactor) would never recover. But the cardinals weren’t going to elect the youngest of the brothers in their midst; and it was most reasonable of them, I willingly confess. For this high office one needs the experience I have since been able to gather. Even so, I already possessed enough to know not to fill my head with vainglorious illusions. Whispering untiringly in the Italians’ ears that never, ever would French cardinals vote for Jacques Fournier, I contrived to bring their votes upon his head, and get him elected unanimously. ‘You have elected an ass!’ was the thanks he shouted at us upon hearing his name proclaimed. He knew his own inadequacies. No, not an ass; but no more a lion either. A good general of the Order, who had long exercised authority at the head of the Carthusian monks and expected to be obeyed. But from there to rule over the whole of Christendom, too meticulous, overzealous, constantly prying. Overall, his reformations had done more harm than good. Only with him, one could be absolutely certain that the Holy See would not return to Rome.1 On that he was solid as a rock, and that was the most important thing.

The second time, during the conclave of 1342 … ah! The second time, I would have been in with a fighting chance if only … if Philip of Valois hadn’t wished to elect his chancellor, the Archbishop of Rouen. We in Périgord have always obeyed the French crown. Furthermore, how could I possibly have continued to be head of the French party if I had dared oppose the king? Besides, Pierre Roger was a great pope, without a shadow of doubt the best I have served. One only has to see what Avignon has become under him, the palace he built, and the influx of men of letters, scholars and artists. And he succeeded in buying Avignon outright. I personally took care of that negotiation with the Queen of Naples; I can safely say that it was my work. Eighty thousand florins, it was nothing, a beggarly sum. Queen Joan had less need for money than for indulgences for all her successive marriages, not to mention her lovers.

They must have put new harnesses on my packhorses by now. My palanquin is far too firm. It is always the way when setting off, always the way. From that moment on, God’s vicar ceases to be a tenant, reluctantly seated on an uncertain throne. And the court that we had! It set an example to the world. All the kings were jostling to get in. To be pope, it is not enough to be a priest, one must also be a prince. Clement VI was a great diplomat; he was always glad to hear my advice. Ah! The maritime league that brought together the Latins of the East, the King of Cyprus, the Venetians, the Knights Hospitaller. We cleansed the Greek archipelago of the barbarians overrunning it; and we were going to do more. But then came this ridiculous war between the French and English kings; I wonder if it will ever end; it has prevented us from furthering our grand design, to bring the Church of the East back into the Roman fold. And then there was the plague, and then Clement passed away.

The third time, during the conclave four years ago, my impediment was, ironically, the fact that I was too princely. Too grand seigneur, too extravagant, it would seem, and we had just had a pope of that very ilk. I, Hélie de Talleyrand, known by my title of Cardinal of Périgord: to think it would have been an insult to the poor to choose me of all people! There are occasions when the Church is seized with a sudden passion for humility, for modesty. Which never does it any good. If we strip ourselves of all ornament, hide our chasubles, sell our golden ciboria and offer the Body of Christ in a two-denier bowl, dress ourselves like yokels, and filthy with it, we are no longer respected by anyone, least of all by the yokels themselves. Indeed! Were we to make ourselves the same as them, why on earth should they honour us? And we end up no longer even respecting ourselves. When you take a stand against this, the staunchly humble stick the gospel under your nose, as if they were the only ones who knew it, and dwell on the nativity, the crib between the ox and the ass, and then it’s the carpenter’s workshop they harp on about. Be like Our Saviour Jesus. But Our Lord, where is He now, my vain little clerics? Isn’t He at the right hand of the Father bathed in His omnipotence? Is He not Christ in majesty enthroned in the light of stars and the music of the heavens? Is He not the king of the world, flanked by legions of seraphs and the blessed? What then is it that entitles you to decree which of these images you should, through your very self, offer to the faithful, that of His fleeting earthly existence or that of His eternal triumph?

Enough. Should I pass through any diocese where I see the bishop rather too willing to disparage God, embracing new ideas, this is what I will preach.

To walk bearing twenty pounds of woven gold, and the mitre, and the crosier, it isn’t pleasant every day, especially when one has been doing so for more than thirty years. But it is necessary.

One can attract more souls with honey than with vinegar. When flea-ridden scum address other flea-ridden scum as ‘my brothers’, it doesn’t produce a great deal of effect. Should a king say it, that is different. Bringing people a little self-esteem is the very first act of kindness, of which our Fratricelles and Gyrovagues2 are unaware. It is precisely because the people are poor, and suffering, and sinners, and destitute, that we must give them reason to believe in the afterlife. Oh yes indeed! With frankincense, gold and music. The Church must offer the faithful a vision of the heavenly kingdom, and every priest, beginning with the pope and his cardinals, should reflect something of the image of the Pantocrator.

It is not such a bad thing after all to talk to myself this way; it helps me find arguments for my forthcoming sermons. Although I prefer to find them when in the company of others. I hope Brunet hasn’t forgotten my sugared almonds. Ah! No, there they are. For that matter, he never forgets.

Although I am not a great theologian as so many of my colleagues are – theologians are thick on the ground these days – I do have responsibility for ensuring order and cleanliness in the house of the good Lord upon this earth, and I refuse to reduce the trappings of my position; not even the pope, who knows only too well what he owes me, has dared to force me to do so. He can waste away on his throne, if he so wishes, that is his own business entirely. But I, his nuncio, am careful to preserve the glory of his office.