Полная версия:

The Scapegoat: One Murder. Two Victims. 27 Years Lost.

Copyright

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published as Town Without Pity by Century,

an imprint of Random House 2002

This revised and updated edition published by HarperElement 2019

FIRST EDITION

© Don Hale 2019

Cover design by Ellie Game © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photograph supplied by the author

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein and secure permissions, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any future edition of this book.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Don Hale asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008331627

Ebook Edition © June 2019 ISBN: 9780008331634

Version: 2019-05-22

Contents

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Contents

6 Cast of Characters

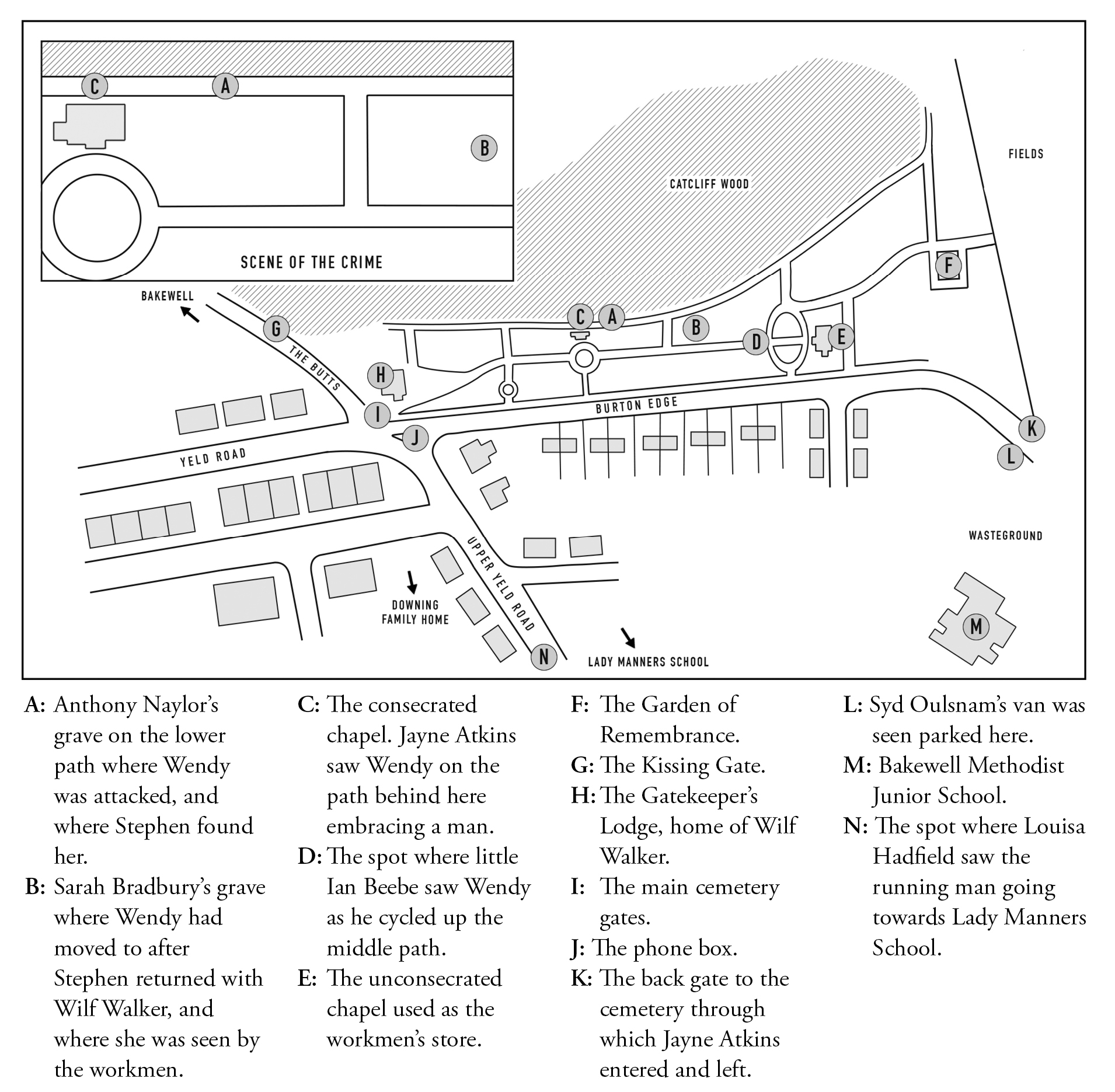

7 Map of Bakewell Cemetery

8 INTRODUCTION

9 1 ‘STEPHEN WHO?’

10 2 THE DOWNINGS

11 3 WHAT RAY SAW

12 4 THE CONFESSION

13 5 THE WITNESSES

14 6 STEPHEN’S VERSION

15 7 BELIEVING THE BEEBES

16 8 THE RUNNING MAN

17 9 PERSONS OF INTEREST: MR ORANGE, MR OULSNAM AND MR RED

18 10 WHO WAS WENDY SEWELL?

19 11 ANATOMY OF A FALSE CONFESSION

20 12 ON THE TRAIL OF MR ORANGE

21 13 WALKING WITH WITNESSES

22 14 THE BOMBSHELL

23 15 THE SMOKING GUN

24 16 GETTING TO KNOW STEPHEN DOWNING

25 17 FACE TO FACE AT LAST

26 18 JUST BECAUSE YOU’RE PARANOID DOESN’T MEAN THEY’RE NOT AFTER YOU

27 19 WALKING IN ROBERT ERVIN’S SHADOW

28 20 CLANDESTINE MEETINGS

29 21 BATTLING BUREAUCRACY

30 22 THE TEA AND CAKES DEPARTMENT

31 23 THE COVER-UP

32 24 MULTIPLE MURDERS

33 25 THE NATIONAL INTEREST

34 26 THE WAITING GAME

35 27 THE LONGEST DAY

36 28 FACE TO FACE AGAIN

37 29 WELCOME HOME

38 30 FREEDOM

39 Epilogue

40 Enjoyed the Book?

41 About the Publisher

LandmarksCoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiiiivvixxxixii123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960616263646566676869707172737475767778798081828384858687888990919293949596979899100101102103104105106107108109110111112113114115116117118119120121122123124125126127128129130131132133134135136137138139140141142143144145146147148149150151152153154155156157158159160161162163164165166167168169170171172173174175176177178179180181182183184185186187188189190191192193194195196197198199200201202203204205206207208209210211212213214215216217218219220221222223224225226227228229230231232233234235236237238239240241242243244245246247248249250251252253254255256257258259260261262263264265266267268269270271272273274275276277278279280281282283284285286287288289290291292293294295296297298299300301302303304305306307308309310311312313314315316317318319320321322323324325326327328329330331332333334335336337338

Cast of Characters

THE VICTIM AND HER FAMILY

Wendy Sewell

David Sewell

John Marshall

THE MAIN SUSPECT AND HIS FAMILY

Stephen Downing

Ray Downing

Juanita Downing

Christine Downing

PERSONS OF INTEREST

Mr Orange

Syd Oulsnam

Mr Red

Mr Blue (the running man)

The businessman

PRIVATE INVESTIGATOR AND INFORMANTS

Robert Ervin

Port Vale

Chelsea

Spurs

DERBYSHIRE POLICE

PC Ernie Charlesworth

PC Ball

Detective Younger

Detective Johnson

Detective Rodney Jones

Detective Superintendent Tom Naylor

Chief Constable John Newing

Deputy Chief Constable Don Dovaston

MATLOCK MERCURY STAFF

Sam Fay

Jackie Dunn

Norman Taylor

Marcus Edwards

Matt Barlow

OTHER JOURNALISTS

Nick Pryer (Mail on Sunday)

Frank Curran (Daily Star)

Matthew Parris (The Times)

Rob Hollingsworth (Sheffield Star)

Allan Taylor (Central Television)

OFFICIALS

Patrick McLoughlin MP

CCRC Commissioner Barry Capon

WITNESSES

Charlie Carman

Wilf Walker

Peter Moran

Mr Watts

Mr Dawson

Louisa Hadfield

George Paling

Marie Bright

Jayne Atkins

Margaret Beebe

Ian Beebe

Lucy Beebe

John Osmaston

Rita

Ms Yellow

Cynthia Smithurst

Yvonne Spencer

Crabby

Steven Martin

Map of Bakewell Cemetery

A: Anthony Naylor’s grave on the lower path where Wendy was attacked, and where Stephen found her.

B: Sarah Bradbury’s grave where Wendy had moved to after Stephen returned with Wilf Walker, and where she was seen by the workmen.

C: The consecrated chapel. Jayne Atkins saw Wendy on the path behind here embracing a man.

D: The spot where little Ian Beebe saw Wendy as he cycled up the middle path.

E: The unconsecrated chapel used as the workmen’s store.

F: The Garden of Remembrance.

G: The Kissing Gate

H: The Gatekeeper’s Lodge, home of Wilf Walker.

I: The main cemetery gates.

J: The phone box.

K: The back gate to the cemetery through which Jayne Atkins entered and left.

L: Syd Oulsnam’s van was seen parked here.

M: Bakewell Methodist Junior School.

N: The spot where Louisa Hadfield saw the running man going towards Lady Manners School.

Introduction

It was a cold, drizzly night in March 1995, and I was working late at the Matlock Mercury office, with no one but my dog Jess for company, when the phone rang. It was a young woman on the other end of the line. She said there was a large fire at a nearby farm, which sounded serious and newsworthy to me.

I quickly grabbed my gear, cameras and all, and jumped in my car with Jess, who snuggled in her blanket on the back seat as we travelled through the bleak Derbyshire hills in the direction of the fire.

It was a challenging road at times, snaking its way through a barren landscape and miles upon miles of desperately bleak moorland. The road seemed totally deserted, and I was in an almost dream-like state navigating the deep dips of this roller-coaster track, when suddenly out of nowhere an enormous truck appeared right behind me, with its powerful headlights and a top searchlight burning into my rear-view mirror.

Dazzled by the lights, I slowed to let it pass, but the truck driver also slackened his speed, and remained directly behind me.

As I reached the location of the fire, all was calm and there wasn’t even a whiff of smoke. I realised I had been the victim of a hoax. It was time to turn the car round and head for home. I swung into a lay-by, steering in a wide arc, and almost clipped the lorry as it clattered past.

That’s the last I’ll see of him, I thought, as I changed up into third gear. But then, to my surprise and shock, I saw this monster in my mirror, with its roaring engine, hissing air brakes and screeching tyres, also perform a spectacular U-turn in my wake.

The darkened cab was now illuminated. The driver appeared to be talking into a CB radio. I pressed down on the accelerator but the lorry was still gaining speed on me, and very rapidly. Jess whimpered softly, so I reached back and patted her head, taking my eyes off the road for a split second – and we almost took off on one of the major dips I subsequently misjudged.

It took a second or two to adjust my vision as the headlight beams bounced back off the dark, shiny road surface. There were no other vehicles on the road; it was just me and my pursuer. I turned off onto the narrow road which led back to Cromford and Matlock, and home – but still he followed.

I put my foot down, but I was now sweating with fear, my hands and legs trembling. It was pitch black apart from the dim lights of some distant farmhouse, and I knew I would have to slow down soon.

I decided to cut off the main road to the left, which would take me back down the valley towards the picturesque villages of Winster and Elton, on an even narrower road. If I could reach there, I’d surely be safe.

The lorry was so close it was almost in the back seat with Jess, and again its bright lights blazed into my mirrors.

I jumped out of my skin when its horn, a deep and very loud siren, blared repeatedly into my ears … and then came the impact. A juddering bump in the rear, jolting my car forward.

The horn sounded again and again, and then another sickening bump. I had to think quickly. In a minute or so the junction down to Elton would appear on my left. Suddenly, I had an idea.

As the fork approached I signalled right then, at the very last moment, jerked the wheel and turned hard left. But the lorry driver copied my actions, clipping a signpost and ploughing over the grass verge in the process.

My head was throbbing, my blood pumping, and, as I wiped the sweat from my face, I knew the road would come to another T-junction in less than two miles. I was pushing 55 mph, as fast as I dared – it was too dark and the road too narrow to go any faster.

The horn sounded again, then another bang. As I was pushed away from each shunt, I noticed the driver was back on his CB radio again. It dawned on me that someone else must be involved.

The junction was now fast approaching, less than half a mile away. I could see a signpost in the distance and noticed a large, dark shape in the middle of the road, which seemed to be growing in size rapidly.

What the hell is it? I wondered, peering into the blackness. Five hundred yards and closing, three hundred and fifty yards and closing quickly.

Two hundred and fifty yards – and I was still travelling fast.

Christ, it’s another truck!

A tipper truck was parked sideways across the road, totally blocking the way. There was a shadowy outline of someone standing near the front of the vehicle. He had some kind of large object in his hand. One hundred yards and my heart was racing. Where could I go?

As if in answer to my desperate plea, my headlights picked out a reflector on a small gatepost about fifty yards ahead. Maybe there was an open gateway into a field. It was too late for anything else. I touched the accelerator then immediately hit the brake and yanked the wheel hard left, ramming the car through the open gateway into a rain-sodden field. There was a terrific bang as the lorry hurtled past. Its airbrakes hissed, screeched and locked, but it was too late for it to stop. It skidded on the wet surface and slid hard into the side of the other truck.

The field sloped downwards slightly and away from the gate. It was a sea of wet grass and mud. I gripped the steering wheel with all my might in a desperate attempt to keep control and somehow managed to turn the car round in a large horseshoe to face the gate again. The rear wheels spun wildly, but I kept up the revs, spun back up the field and hastily drove back out of the same gate.

I didn’t bother to look either way as I pulled out and roared back down the road. I was soaked with sweat, and through my rear-view mirror I could see white smoke and steam pouring from one of the lorries. Jess barked in defiance and, as I turned to offer a comforting hand, I noticed the driver-side mirror now hanging by a thread – just as my life had been.

All the way home I kept checking the rear-view mirror, any headlights causing my mind to whirl in a frenzy of paranoia and anxiety. The adrenaline continued to pour through my body.

Someone was definitely trying to kill me. I knew they had tried before, and it seemed certain that they would try again.

Yet I kept asking myself, if Stephen Downing had killed Wendy Sewell, why would anyone want to get rid of me?

CHAPTER 1

‘Stephen Who?’

There was nothing auspicious about that particular Monday, 14 March 1994. Certainly nothing to suggest that it would put in motion events that would help to change so many lives, and make an indelible mark on both British and European law.

In fact, the day started in domestic chaos, as I forgot to set the alarm following a late-night return from Amsterdam. My wife, Kath, had no choice but to dash off for work, while I did the school run, dropping off my youngest boy at Highfields School, and on the way back admired the spectacular panoramic view across Matlock and the Derbyshire Dales.

After a few days of luxury in Amsterdam it felt good to be home, and I was relieved to be heading back to reality at the Matlock Mercury. I was termed a ‘foreigner’ by many of the locals when I first moved to Matlock from Manchester. I was an outsider. But it was home for me now, the latest stop in a career in journalism that had seen me work for the likes of the BBC, the Manchester Evening News, and most recently the Bury Messenger, before the opportunity to head up the Mercury came along.

I parked up at the side of the office, and said hello to our stray tabby cat, who would often perch precariously on the upper window ledge, looking at us with a mischievous grin and probably thanking his lucky stars he didn’t have to work in our building, a former print works that had definitely seen better days.

As I entered via the back door, I could hear the old typewriters clattering away and see my reporters going about their business.

‘Good morning, everyone,’ I said cheerfully, hoping they hadn’t noticed that I was ten minutes late. ‘Anything special happened since I’ve been away?’

Jackie Dunn, one of my young journalists, cheekily asked if my flight had been delayed, before she gave me a brief summary of events from the previous week.

My sports editor Norman Taylor, a retired train driver, said Matlock Town had still not scored – but had won a corner, a comment that earned a glare from Sam Fay, my deputy editor. A war veteran in his late sixties, he worked on a part-time basis, covering match reports and local politics.

I took my jacket off, settled down and began to plough my way through all the paperwork, while I asked Sam for a meeting to discuss stories for the next edition.

The small sliding window in the frosted glass partition, which divided editorial from the advertising department, suddenly slid open with a loud bang.

The receptionist announced, ‘Don, there’s a man wanting to make an appointment with you. He says it’s something about a murder.’

She cupped her hand over the receiver. ‘Do you want to take the call?’ she asked. ‘It’s something to do with his son, Stephen.’

I beckoned to her to put the call through.

When I answered, the man chatted away at ten to the dozen. It was like trying to decipher a verbal machine gun. ‘Stephen who?’ I asked.

‘Stephen Downing,’ came the reply, sounding rather agitated, as if I should know all about him. The man explained that he was his father, Ray, and claimed his son was still in jail after 20-something years for a murder he didn’t commit.

He said the murder had occurred in the cemetery at Bakewell, a pretty, picture-postcard market town in the Peak District, about eight miles away. I let him continue for a while before I interrupted, saying, ‘It’s all right, Mr Downing …’

‘Call me Ray,’ he quickly replied.

‘Okay then, Ray. You don’t have to make an appointment to see me. I’m usually here from dawn till dusk.’ I found it very difficult to take in half of what he’d said to me over the phone. ‘Yes, Ray, 2.30 p.m. today is fine. And bring some paperwork with you if you wish. I’m not sure what I can do but I’ll have a look.’

I looked round to see that some of my team were also listening. I told them, ‘It’s a Mr Downing, who says it’s something to do with an old murder involving his son. I think he said it was in 1973. He’s a local taxi driver, and both he and his wife want to see me today. This afternoon, in fact.’

Sam pulled out a cigarette and lit it. He frowned at me, and half spluttered, ‘Don, I will have to go out for a short while but I’ll speak with you later. We must have a chat about this Stephen Downing.’ With that he disappeared in a trail of smoke.

* * *

At precisely 2.30 p.m. there was a knock on my office door. ‘A Mr and Mrs Downing to see you, Don. They have an appointment?’ said Susan, one of our advertising reps.

‘Yes, of course, show them in, please,’ I replied, and ushered the pair into my private office. Ray Downing was struggling to hold a large pile of documents, which he then dumped firmly on my desk. I had to move them aside slightly so I could see their faces.

Ray was a fairly small man with a bald head and a worried expression. I guessed he was probably in his late fifties or early sixties. His wife, whom he introduced as Juanita, was about the same age. She looked quite frail and had sharp, almost bird-like features. She was very nervous and extremely thin. Both wore their Sunday best.

Ray outlined his reasons for contacting me. He claimed his son Stephen had been jailed in 1974 for the murder of a woman in the town cemetery the previous year. Ray kept saying he was innocent, and that everyone in Bakewell knew he was innocent. He kept stressing that word.

‘What’s more,’ said Ray, ‘I can probably tell you who was responsible. Nearly everyone in Bakewell seems to know who did it.’

I was taken aback by his comments. Ray didn’t mention any name, but I was puzzled by his claim and wondered, If it was all so obvious, why was his lad still in jail?

Ray alleged that Stephen had been framed for the murder as part of a conspiracy because the town needed someone else to blame. He claimed the police forced Stephen to wrongfully confess to an assault on a young, married woman, who later died from her injuries.

Ray claimed the woman, Wendy Sewell, was promiscuous, and had taken several prominent local businessmen as lovers. He suggested a long list of individuals, and said they were all well known in the Bakewell area. He believed the powers that be in the town had conspired to protect the victim’s secret life, and perhaps themselves, from a massive scandal.

He explained that several other characters had been seen in or around the cemetery on the day of the attack, and that potential witnesses had either been ignored by the police or deliberately warned off.

He strongly believed that one particular officer, who ‘had it in for Stephen’, went flat-out to get a quick confession. Ray said that although his son quickly retracted it, the confession still formed the main plank of the prosecution evidence from which he was convicted.

Ray said there had been some previous attempts to obtain an appeal against conviction, the first being in October 1974, a few months after his trial, and the second some 13 years before, in 1981. Both failed. He then admitted to hiring a private investigator, Robert Ervin, a former army investigator, who worked on the case for about ten years but died some time ago.

Juanita let Ray do most of the talking. She looked uncomfortable and agitated, and began fumbling through the paperwork, before extracting some old cuttings that reported the previous attempts to appeal. She explained that the rest of the paperwork included court papers, copies of some old witness statements from years ago and various other official reports she thought I might find of interest.

Ray was anxious to continue, and he confirmed that the reason they wanted to see me that day was because a woman had telephoned them anonymously to say she had sent both me and the editor of the Star some fresh evidence that could help clear their son’s name.

‘The Star?’ I asked. ‘Do you mean the Sheffield Star or the Daily Star?’

‘Don’t know, she just said the Star.’

‘Look, I’ve just returned from a short break,’ I said. ‘I don’t think anything’s arrived here, nobody has mentioned anything, but I’ll go and check.’ I brushed past them and made my way to the main office.

‘Does anyone know anything about a letter concerning Stephen Downing?’ I asked. ‘His parents think some fresh evidence may have been sent here.’ Everyone shook their heads.

Jackie said, ‘Whatever came in that we couldn’t deal with is on your desk. I don’t recall anything about a Stephen Downing, though.’

‘What’s this all about?’ asked Norman.

‘I’m not quite sure at this stage, but their son Stephen has been in jail for murder for over 20 years. They are desperate and need a lifeline. I’ll ask Sam when he comes back,’ I replied.

I returned to my office and told the Downings that nothing had been received so far, but that I had contacts at both newspapers and would get back to them as soon as I could. We made arrangements to meet a day or two later at their home in Bakewell.