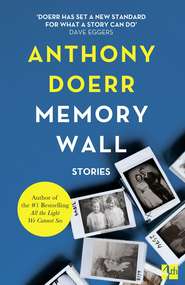

Полная версия:

Memory Wall

ANTHONY DOERR

Memory Wall

FOURTH ESTATE • London

Copyright

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This Fourth Estate paperback edition published 2012

First published in hardback by Fourth Estate in 2011

Copyright © Anthony Doerr 2010

Cover photograph © www.mat-taylor.co.uk/photography

‘The Deep’ was first published by the Sunday Times

Anthony Doerr asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9780007367726

Ebook Edition © NOVEMBER 2011 ISBN: 9780007367740

Version: 2017-05-22

For Shauna

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Memory Wall

Procreate, Generate

The Demilitarized Zone

Village 113

The River Nemunas

Afterworld

The Deep

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Reviews

Read On…

By the same author

About the Publisher

Memory Wall

TALL MAN IN THE YARD

Seventy-four-year-old Alma Konachek lives in Vredehoek, a suburb above Cape Town: a place of warm rains, big-windowed lofts, and silent, predatory automobiles. Behind her garden, Table Mountain rises huge, green, and corrugated; beyond her kitchen balcony, a thousand city lights wink and gutter behind sheets of fog like candleflames.

One night in November, at three in the morning, Alma wakes to hear the rape gate across her front door rattle open and someone enter her house. Her arms jerk; she spills a glass of water across the nightstand. A floorboard in the living room shrieks. She hears what might be breathing. Water drips onto the floor.

Alma manages a whisper. “Hello?”

A shadow flows across the hall. She hears the scrape of a shoe on the staircase, then nothing. Night air blows into the room—it smells of frangipani and charcoal. Alma presses a fist over her heart.

Beyond the balcony windows, moonlit pieces of clouds drift over the city. Spilled water creeps toward her bedroom door.

“Who’s there? Is someone there?”

The grandfather clock in the living room pounds through the seconds. Alma’s pulse booms in her ears. Her bedroom seems to be rotating very slowly.

“Harold?” Alma remembers that Harold is dead but she cannot help herself. “Harold?”

Another footstep from the second floor, another protest from a floorboard. What might be a minute passes. Maybe she hears someone descend the staircase. It takes her another full minute to summon the courage to shuffle into the living room.

Her front door is wide open. The traffic light at the top of the street flashes yellow, yellow, yellow. The leaves are hushed, the houses dark. She heaves the rape gate shut, slams the door, sets the bolt, and peers out the window lattice. Within twenty seconds she is at the hall table, fumbling with a pen.

A man, she writes. Tall man in the yard.

MEMORY WALL

Alma stands barefoot and wigless in the upstairs bedroom with a flashlight. The clock down in the living room ticks and ticks, winding up the night. A moment ago Alma was, she is certain, doing something very important. Something life-and-death. But now she cannot remember what it was.

The one window is ajar. The guest bed is neatly made, the coverlet smooth. On the nightstand sits a machine the size of a microwave oven, marked Property of Cape Town Memory Research Center. Three cables spiraling off it connect to something that looks vaguely like a bicycle helmet.

The wall in front of Alma is smothered with scraps of paper. Diagrams, maps, ragged sheets swarming with scribbles. Shining among the papers are hundreds of plastic cartridges, each the size of a matchbook, engraved with a four-digit number and pinned to the wall through a single hole.

The beam of Alma’s flashlight settles on a color photograph of a man walking out of the sea. She fingers its edges. The man’s pants are rolled to the knees; his expression is part grimace, part grin. Cold water. Across the photo, in handwriting she knows to be hers, is the name Harold. She knows this man. She can close her eyes and recall the pink flesh of his gums, the folds in his throat, his big-knuckled hands. He was her husband.

Around the photo, the scraps of paper and plastic cartridges build outward in crowded, overlapping layers, anchored with pushpins and chewing gum and penny nails. She sees to-do lists, jottings, drawings of what might be prehistoric beasts or monsters. She reads: You can trust Pheko. And Taking Polly’s Coca-Cola. A flyer says: Porter Properties. There are stranger phrases: dinocephalians, late Permian, massive vertebrate graveyard. Some sheets of paper are blank; others reveal a flurry of cross-outs and erasures. On a half-page ripped from a brochure, one phrase is shakily and repeatedly underlined: Memories are located not inside the cells but in the extracellular space.

Some of the cartridges have her handwriting on them, too, printed below the numbers. Museum. Funeral. Party at Hattie’s.

Alma blinks. She has no memory of writing on little cartridges or tearing out pages of books and tacking things to the wall.

She sits on the floor in her nightgown, legs straight out. A gust rushes through the window and the scraps of paper come alive, dancing, tugging at their pins. Loose pages eddy across the carpet. The cartridges rattle lightly.

Near the center of the wall, her flashlight beam again finds the photograph of a man walking out of the sea. Part grimace, part grin. That’s Harold, she thinks. He was my husband. He died. Years ago. Of course.

Out the window, beyond the crowns of the palms, beyond the city lights, the ocean is washed in moonlight, then shadow. Moonlight, then shadow. A helicopter ticks past. The palms flutter.

Alma looks down. There is slip of paper in her hand. A man, it says. Tall man in the yard.

DR. AMNESTY

Pheko is driving the Mercedes. Apartment towers reflect the morning sun. Sedans purr at stoplights. Six different times Alma squints out at the signs whisking past and asks him where they are going.

“We’re driving to see the doctor, Mrs. Alma.”

The doctor? Alma rubs her eyes, unsure. She tries to fill her lungs. She fidgets with her wig. The tires squeal as the Mercedes climbs the ramps of a parking garage.

Dr. Amnesty’s staircase is stainless steel and bordered with ferns. Here’s the bulletproof door, the street address stenciled in the corner. It’s familiar to Alma in the way a house from childhood would be familiar. As if she has doubled in size in the meantime.

They are buzzed into a waiting room. Pheko drums his fingertips on his knee. Four chairs down, two well-dressed women sit beside a fish tank, one a few decades younger than the other. Both have fat pearls studded through each earlobe. Alma thinks: Pheko is the only black person in the building. For a moment she cannot remember what she is doing here. But this leather on the chair, the blue gravel in the saltwater aquarium—it is the memory clinic. Of course. Dr. Amnesty. In Green Point.

After a few minutes Alma is escorted to a padded chair overlaid with crinkly paper. It’s all familiar now: the cardboard pouch of rubber gloves, the plastic plate for her earrings, two electrodes beneath her blouse. They lift off her wig, rub a cold gel onto her scalp. The television panel shows sand dunes, then dandelions, then bamboo.

Amnesty. A ridiculous surname. What does it mean? A pardon? A reprieve? But more permanent than a reprieve, isn’t it? Amnesty is for wrongdoings. For someone who has done something wrong. She will ask Pheko to look it up when they get home. Or maybe she will remember to look it up herself.

The nurse is talking.

“And the remote stimulator is working well? Do you feel any improvements?”

“Improvements?” She thinks so. Things do seem to be improving. “Things are sharper,” Alma says. She believes this is the sort of thing she is supposed to say. New pathways are being forged. She is remembering how to remember. This is what they want to hear.

The nurse murmurs. Feet whisper across the floor. Invisible machinery hums. Alma can feel, numbly, the rubber caps being twisted out of the ports in her skull and four screws being threaded simultaneously into place. There is a note in her hand: Pheko is in the waiting room. Pheko will drive Mrs. Alma home after her session. Of course.

A door with a small, circular window in it opens. A pale man in green scrubs sweeps past, smelling of chewing gum. Alma thinks: There are other padded chairs in this place, other rooms like this one, with other machines prying the lids off other addled brains. Ferreting inside them for memories, engraving those memories into little square cartridges. Attempting to fight off oblivion.

Her head is locked into place. Aluminum blinds clack against the window. In the lulls between breaths, she can hear traffic sighing past.

The helmet comes down.

THREE YEARS BEFORE, BRIEFLY

“Memories aren’t stored as changes to molecules inside brain cells,” Dr. Amnesty told Alma during her first appointment, three years ago. She had been on his waiting list for ten months. Dr. Amnesty had straw-colored hair, nearly translucent skin, and invisible eyebrows. He spoke English as if each word were a tiny egg he had to deliver carefully through his teeth.

“This is what they thought forever but they were wrong. The truth is that the substrate of old memories is located not inside the cells but in the extracellular space. Here at the clinic we target those spaces, stain them, and inscribe them into electronic models. In the hopes of teaching damaged neurons to make proper replacements. Forging new pathways. Re-remembering.

“Do you understand?”

Alma didn’t. Not really. For months, ever since Harold’s death, she had been forgetting things: forgetting to pay Pheko, forgetting to eat breakfast, forgetting what the numbers in her checkbook meant. She’d go to the garden with the pruners and arrive there a minute later without them. She’d find her hairdryer in a kitchen cupboard, car keys in the tea tin. She’d rummage through her mind for a noun and come up empty-handed: Casserole? Carpet? Cashmere?

Two doctors had already diagnosed the dementia. Alma would have preferred amnesia: a quicker, less cruel erasure. This was a corrosion, a slow leak. Seven decades of stories, five decades of marriage, four decades of working for Porter Properties, too many houses and buyers and sellers to count—spatulas and salad forks, novels and recipes, nightmares and daydreams, hellos and goodbyes. Could it all really be wiped away?

“We don’t offer a cure,” Dr. Amnesty was saying, “but we might be able to slow it down. We might be able to give you some memories back.”

He set the tips of his index fingers against his nose and formed a steeple. Alma sensed a pronouncement coming.

“It tends to unravel very quickly, without these treatments,” he said. “Every day it will become harder for you to be in the world.”

Water in a vase, chewing away at the stems of roses. Rust colonizing the tumblers in a lock. Sugar eating at the dentin of teeth, a river eroding its banks. Alma could think of a thousand metaphors, and all of them were inadequate.

She was a widow. No children, no pets. She had her Mercedes, a million and a half rand in savings, Harold’s pension, and the house in Vredehoek. Dr. Amnesty’s procedure offered a measure of hope. She signed up.

The operation was a fog. When she woke, she had a headache and her hair was gone. With her fingers she probed the four rubber caps secured into her skull.

A week later Pheko drove her back to the clinic. One of Dr. Amnesty’s nurses escorted her to a leather chair that looked something like the ones in dental offices. The helmet was merely a vibration at the top of her scalp. They would be reclaiming memories, they said; they could not predict if the memories would be good ones or bad ones. It was painless. Alma felt as though spiders were stringing webs though her head.

Two hours later Dr. Amnesty sent her home from that first session with a remote memory stimulator and nine little cartridges in a paperboard box. Each cartridge was stamped from the same beige polymer, with a four-digit number engraved into the top. She eyed the remote player for two days before taking it up to the upstairs bedroom one windy noon when Pheko was out buying groceries.

She plugged it in and inserted a cartridge at random. A low shudder rose through the vertebrae of her neck, and then the room fell away in layers. The walls dissolved. Through rifts in the ceiling, the sky rippled like a flag. Then Alma’s vision snuffed out, as if the fabric of her house had been yanked downward through a drain, and a prior world rematerialized.

She was in a museum: high ceiling, poor lighting, a smell like old magazines. The South African Museum. Harold was beside her, leaning over a glass-fronted display, excited, his eyes shining—look at him! So young! His khakis were too short, black socks showed above his shoes. How long had she known him? Maybe six months?

She had worn the wrong shoes: tight, too rigid. The weather had been perfect that day and Alma would have preferred to sit in the Company Gardens under the trees with this tall new boyfriend. But the museum was what Harold wanted and she wanted to be with him. Soon they were in a fossil room, a couple dozen skeletons on podiums, some as big as rhinos, some with yardlong fangs, all with massive, eyeless skulls.

“One hundred and eighty million years older than the dinosaurs, hey?” Harold whispered.

Nearby, schoolgirls chewed gum. Alma watched the tallest of them spit slowly into a porcelain drinking fountain, then suck the spit back into her mouth. A sign labeled the fountain For Use by White Persons in careful calligraphy. Alma felt as if her feet were being crushed in vises.

“Just another minute,” Harold said.

Seventy-one-year-old Alma watched everything through twenty-four-year-old Alma. She was twenty-four-year-old Alma! Her palms were damp and her feet were aching and she was on a date with a living Harold! A young, skinny Harold! He raved about the skeletons; they looked like animals mixed with animals, he said. Reptile heads on dog bodies. Eagle heads on hippo bodies. “I never get tired of seeing them,” young Harold was telling young Alma, a boyish luster in his face. Two hundred and fifty million years ago, he said, these creatures died in the mud, their bones compressed slowly into stone. Now someone had hacked them out; now they were reassembled in the light.

“These were our ancestors, too,” Harold whispered. Alma could hardly bear to look at them: They were eyeless, fleshless, murderous; they seemed engineered only to tear one another apart. She wanted to take this tall boy out to the gardens and sit hip-to-hip with him on a bench and take off her shoes. But Harold pulled her along. “Here’s the gorgonopsian. A gorgon. Big as a tiger. Two, three hundred kilograms. From the Permian. That’s only the second complete skeleton ever found. Not so far from where I grew up, you know.” He squeezed Alma’s hand.

Alma felt dizzy. The monster had short, powerful legs, fist-size eyeholes, and a mouth full of fangs. “Says they hunted in packs,” whispered Harold. “Imagine running into six of those in the bush?” In the memory twenty-four-year-old Alma shuddered.

“We think we’re supposed to be here,” he continued, “but it’s all just dumb luck, isn’t it?” He turned to her, about to explain, and as he did shadows rushed in from the edges like ink, flowering over the entire scene, blotting the vaulted ceiling, and the schoolgirl who’d been spitting into the fountain, and finally young Harold himself in his too small khakis. The remote device whined; the cartridge ejected; the memory crumpled in on itself.

Alma blinked and found herself clutching the footboard of her guest bed, out of breath, three miles and five decades away. She unscrewed the headgear. Out the window a thrush sang chee-chweeeoo. Pain swung through the roots of Alma’s teeth. “My god,” she said.

THE ACCOUNTANT

That was three years ago. Now a half dozen doctors in Cape Town are harvesting memories from wealthy people and printing them on cartridges, and occasionally the cartridges are traded on the streets. Old-timers in nursing homes, it’s been reported, are using memory machines like drugs, feeding the same ratty cartridges into their remote machines: wedding night, spring afternoon, bike-ride-along-the-cape. The little plastic squares smooth and shiny from the insistence of old fingers.

Pheko drives Alma home from the clinic with fifteen new cartridges in a paperboard box. She does not want to nap. She does not want the triangles of toast Pheko sets on a tray beside her chair. She wants only to sit in the upstairs bedroom, hunched mute and sagging in her armchair with the headgear of the remote device screwed into the ports in her head and occasional strands of drool leaking out of her mouth. Living less in this world than in some synthesized Technicolor past where forgotten moments come trundling up through cables.

Every half hour or so, Pheko wipes her chin and slips one of the new cartridges into the machine. He enters the code and watches her eyes roll back. There are almost a thousand cartridges pinned to the wall in front of her; hundreds more lie in piles across the carpet.

Around four the accountant’s BMW pulls up to the house. He enters without knocking, calls “Pheko” up the stairs. When Pheko comes down the accountant already has his briefcase open on the kitchen table and is writing something in a file folder. He’s wearing loafers without socks and a peacock-blue sweater that looks abundantly soft. His pen is silver. He says hello without looking up.

Pheko greets him and puts on the coffeepot and stands away from the countertop, hands behind his back. Trying not to bend his neck in a show of sycophancy. The accountant’s pen whispers across the paper. Out the window mauve-colored clouds reef over the Atlantic.

When the coffee is ready Pheko fills a mug and sets it beside the man’s briefcase. He continues to stand. The accountant writes for another minute. His breath whistles through his nose. Finally he looks up and says, “Is she upstairs?”

Pheko nods.

“Right. Look. Pheko. I got a call from that … physician today.” He gives Pheko a pained look and taps his pen against the table. Tap. Tap. Tap. “Three years. And not a lot of progress. Doc says we merely caught it too late. He says maybe we forestalled some of the decay, but now it’s over. The boulder’s too big to put brakes on it now, he said.”

Upstairs Alma is quiet. Pheko looks at his shoetops. In his mind he sees a boulder crashing through trees. He sees his five-year-old son, Temba, at Miss Amanda’s school, ten miles away. What is Temba doing at this instant? Eating, perhaps. Playing soccer. Wearing his eyeglasses.

“Mrs. Konachek requires twenty-four-hour care,” the accountant says. “It’s long overdue. You had to see this coming, Pheko.”

Pheko clears his throat. “I take care of her. I come here seven days a week. Sunup to sundown. Many times I stay later. I cook, clean, do the shopping. She’s no trouble.”

The accountant raises his eyebrows. “She’s plenty of trouble, Pheko, you know that. And you do a fine job. Fine job. But our time’s up. You saw her at the boma last month. Doc says she’ll forget how to eat. She’ll forget how to smile, how to speak, how to go to the toilet. Eventually she’ll probably forget how to swallow. Fucking terrible fate if you ask me. Who deserves that?”

The wind in the palms in the garden makes a sound like rain. There is a creak from upstairs. Pheko fights to keep his hands motionless behind his back. He thinks: If only Mr. Konachek were here. He’d walk in from his study in a dusty canvas shirt, safety goggles pushed up over his forehead, his face looking like it had been boiled. He’d drink straight from the coffeepot and hang his big arm around Pheko’s shoulders and say, “You can’t fire Pheko! Pheko’s been with us for fifteen years! He has a little boy now! Come on now, hey?” Winks all around. Maybe a clap on the accountant’s back.

But the study is dark. Harold Konachek has been dead for more than four years. Mrs. Alma is upstairs, hooked into her machine. The accountant slips his pen into a pocket and buckles the latches on his briefcase.

“I could stay in the house, with my son,” tries Pheko. “We could sleep here.” Even to his own ears, the plea sounds small and hopeless.

The accountant stands and flicks something invisible off the sleeve of his sweater. “The house goes on the market tomorrow,” he says. “I’ll deliver Mrs. Konachek to Suffolk Home next week. No need to pack things up while she’s still here; it’ll only frighten her. You can stay on till next Monday.”

Then he takes his briefcase and leaves. Pheko listens to his car glide away. Alma starts calling from upstairs. The accountant’s coffee mug steams untouched.

TREASURE ISLAND

At sunset Pheko poaches a chicken breast and lays a stack of green beans beside it. Out the window flotillas of rainclouds gather over the Atlantic. Alma stares into her plate as if at some incomprehensible puzzle. Pheko says, “Doctor find some good ones this morning, Mrs. Alma?”

“Good ones?” She blinks. The grandfather clock in the living room ticks. The room flickers with a rich, silvery light. Pheko is a pair of eyeballs, a smell like soap. “Old ones,” Alma says.

He helps her into her nightgown and squirts a cylinder of toothpaste onto her toothbrush. Then her pills. Two white. Two gold. Alma clambers into bed muttering questions.

Wind-borne rain starts a gentle patter on the windows. “Okay, Mrs. Alma,” Pheko says. He pulls the quilt up to her throat. “I got to go home.” His hand is on the lamp. His telephone is vibrating in his pocket.

“Harold,” Alma says. “Read to me.”

“I’m Pheko, Mrs. Alma.”

ANTHONY DOERR

Alma shakes her head. “Goddammit.”

“You’ve torn your book all apart, Mrs. Alma.”

“I have? I have not. Someone else did that.”

A breath. A sigh. On the dresser, three lustrous wigs sit atop featureless porcelain heads. “Ten minutes,” Pheko says. Alma lays back, bald, glazed, a withered child. Pheko sits in the bedside chair and takes Treasure Island off the nightstand. Pages fall out when he opens it.

He reads the first paragraphs from memory. I remember him as if it were yesterday, as he came plodding to the inn door, his sea chest following behind him in a hand-barrow; a tall, strong, heavy, nut-brown man …