скачать книгу бесплатно

I gulp in a few mouthfuls of fresh air and try to think of any topic of conversation that will get us away from the school cuisine. Luckily, a large barrack-shaped building looms up in front of us.

“There it is,” says Penny. “It used to be a lunatic asylum, you know.”

“Really,” I say, thinking back to Dad’s remark. “It doesn’t look a bit like it does in the photograph.”

“That was taken from the other side,” says Penny. “The side you see when you’re in the head mistress’s garden—which you are on Commemoration Day and Sports Day if you’re lucky.”

“What are they doing?” I say, pointing to a group of girls engaged in sawing up a tree.

“Activities. It’s part of Grimmer’s ‘Survival In The Seventies’ programme. She’ll tell you all about it.”

We swing through a gate and past a sign which says “Girls drive carefully” and I feel butterflies invading my tummy. What will Miss Grimshaw be like? Will I be able to make the right impression? Despite what Guy and Penny have said about the school, its sheer size takes my breath away. Everywhere I look there are acres of playing fields. It is like Epping forest with fewer trees.

“Who was that?” I say. We have just passed an elderly, brawny looking man with mutton chop whiskers and a sun bronzed complexion. He is wearing a pair of dungarees and an ear to ear leer. Some women might find him attractive in a rather brutish way but I prefer something more sensitive.

“That’s Ruben Hardakre. He and his son, Seth look after the playing fields. You can tell when the girls are maturing. They start prefering Ruben to Seth.”

“Which do you prefer?” I ask.

“I like them both,” smiles Penny.

The drive seems like an extension of the A3 and I don’t envy the milkman. At the top there is a large circle of gravel and a doorway like the entrance to Westminster Abbey.

“I’ll drop you here,” says Penny. “You can have a chat with Grimmers and pop over to the East wing. I’ll wait for you there. You can gobble a spot of entro vioform before we have lunch.”

I do wish I knew when Penny was joking.

I go into the dark hallway and up an even darker flight of stairs. The last house like this I saw had Count Dracula’s slippers beside the front door. Penny might have shown me the way before she scooted off.

I get to the top of the stairs and listen for sounds of life. Nothing. Maybe everybody has gone to dinner, it is twelve thirty. I should never have listened to Penny. She means well but she causes more trouble than Muhammad Ali at a Peace Corps cocktail party. I am considering tip-toeing away when I hear the sound of heavy breathing—in fact, it is not so much heavy breathing as snoring.

I peer into an office and see a large woman asleep with her head in a filing tray. Every time she breathes out, the corners of the papers vibrate. There is a typewriter nearby, and also, a bottle of whisky which has slightly less scotch in it than the glass it is standing next to. Who is this woman? Is it Miss Grimshaw’s secretary or could it be—?

“Miss Grimshaw?” I murmur.

“Just a small one.” The answer comes back immediately but the head does not move. The lady must obviously be very tired.

“You wanted to see me,” I say, apologetically.

“Put it down on my account.” A thin trickle of spittle leaks from the corner of the mouth like syrup from a spoon.

“I’ve come about the job of assistant sports mistress.”

“WHAT!!?” The woman’s head jerks up and I nearly jump out of my skin. “Do you usually creep into people’s rooms like that?”

“I’m sorry,” I gulp.

“I should think so.” The speaker wipes her mouth with a piece of carbon paper and knocks over the whisky bottle. “Cold tea,” she says.

“What?”

“I said ‘cold tea’.”

“No thank you. I had something on the train.”

The woman looks at me as if I am mad. “I meant, it’s cold tea in this bottle. A prop for the school play we’re going to do one day.” She picks up the bottle, bangs home the stopper with the flat of her hand and drops it into a drawer. There is a loud clink suggesting that other props have found a home there. “You were supposed to be here at twelve, weren’t you?”

“The train was a bit late,” I lie.

Miss Grimshaw takes a swig of her cold tea and allows a long shudder to pass through her large frame. “The service is appalling. The whole country is going to the dogs. It’s institutions such as our own which represent the only alternative to a descent into barbarism.”

I am murmuring my agreement when I hear the sound of shrill, girlish voices outside the window. They seem to be excited and the volume is rising fast. Miss Grimshaw says something I can’t quite catch and strides purposefully to the window. I fall in respectfully at her elbow. Below us, the figure of a man can be seen staggering across the circle of gravel. He is wearing a T-shirt—or rather, was wearing a T-shirt. The tattered rag streaming from his broad sun-bronzed shoulders could have been nothing else. The man must be in his early twenties and is definitely a bit of all right in the fanciable stakes. As we watch he darts a glance over his shoulder and the look of haunted terror in his eyes is plain to see. He takes another step forward and collapses on the gravel.

“Blast!” says Miss Grimshaw.

Round a corner of the building stream about twenty girls wearing shorts and blouses. There is a collective shout of triumph and the prostrate man rises on his elbows and starts trying to crawl towards the house we are standing in. Miss Grimshaw throws herself at the window and wrenches up the sash.

“GET BACK!!” she bellows. “BACK! I say.”

The leading girls have now nearly closed with the man who has stopped crawling and curled himself up like a hedgehog. They stumble to a halt and stare up at the window resentfully.

“Back to your rooms!”

There is a moment’s hesitation and then the girls begin to split up into groups and file away. The man picks himself up and raises an accusing finger towards our window.

“I want to see ’ee, Miss Grimshaw.”

“Later, Hardakre.” Miss Grimshaw slams the window down and shakes her head. “Sport plays an important part in our lives here,” she says. “That was the Hare and Hounds Club simulating a kill.” She takes another swig of cold tea. “What was I talking about?”

“About the railways,” I say.

“Erosion of modern values … duty to uphold law and order … Capital Gains Tax …” Miss Grimshaw sways and collapses into her chair. “It’s those pills I have to take for my hay fever.”

“They’re terrible, aren’t they?” I say sympathetically.

Miss Grimshaw shakes her head and picks up a letter with “final demand” typed across the top of it. “Was Geography your only subject at Mingehampton?”

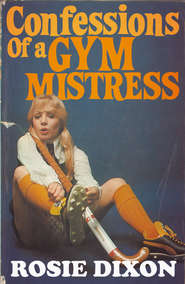

“I think there must be some mistake,” I say. “I came about the job of gym mistress.”

Miss Grimshaw waves a hand at my words as if they are distracting insects. “We can’t have you incarcerated in the gym all the time—anyway, we don’t have one. These days, during the grave shortage of teachers and—er, money considerations prompt us to double up as much as we can. I don’t think you’ll have any problem teaching Geography. After all, you did find your way here.” Miss Grimshaw laughs at her little joke and stretches out a hand to where the bottle of cold tea used to be.

“Well, if you really think—I don’t have any qualifications.”

Miss Grimshaw smiles knowingly. “Don’t worry too much about that. Many of our longest serving members of the staff don’t have any qualifications.”

It all seems too good to be true. Miss Grimshaw is talking as if I already have the job. I must appear keen.

“Pen—Miss Green mentioned the ‘Survival In The Seventies’ Course.”

“Ah yes.” Miss Grimshaw leans forward and places the palms of her hands together. “That’s a project very dear to my heart.”

I flash on my “tell me more” expression but it is unnecessary.

“I think it absolutely vital that we prepare our gels for the world that they are going to have to live in. A world in which oil, coal and even food are going to be in increasingly short supply. Here at St Rodence we bring our gels face to face with these realities from the earliest possible moment. Sometimes a meal is dropped without notice and I have discontinued the oil deliveries so that we can use the raw materials existing in the grounds.”

“I saw some girls sawing up trees,” I say.

“Exactly. And then there’s Miss Bondage’s Open Cast Coal Mining Class. At all levels we’re trying to back up the government’s economy measures.”

“It must save a lot of money, too,” I say.

Miss Grimshaw looks up sharply. “Money. Yes, I suppose that must be a consideration to some people.” The way she says it makes me feel ashamed. How could I have been so clumsy?

“I didn’t mean—” I say hurriedly.

“Don’t.” Miss Grimshaw fans herself with a letter from a firm called Humpbach, Straynes and Croucher. “We live in venal times. It’s understandable that the thought should occur to you. For somebody of my ascetic temperament money hardly enters into the scheme of things.” I nod, wishing that I could understand. Maybe, after exposure to this remarkable woman—“I believe you’ve worked with Miss Green before?”

“Yes, we nursed together.”

“Splendid gel. Her pupils worship her stud marks. I think we’ve got all the makings of a great hockey team this year. Probably our best since the palmy days of Mabel Atherstone-Hinkmore. A big girl but so light on her feet. She moved like a great fairy.” Dad often says the same thing when he is watching the telly. “I think we’re really going to give St Belters a game, this year.”

I nod vigorously and try and make my eyes glow with enthusiasm. Miss Grimshaw’s eyes are glowing with enthusiasm—or something.

“I’d certainly like to help.” I say.

“Good gel!” Miss Grimshaw tries to rise to her feet and then falls back into her chair. “You cut along and take tiffin with Miss Green. She’ll show you the ropes. I must get on with preparing my weekly jaw on current affairs.” Her hand stretches out towards a copy of Sporting Life. “Goodbye, Miss Nixon. Nixon—” Miss G. shakes her head quizzically “—it’s funny, I’m certain I’ve heard that name before somewhere.” Miss Grimshaw obviously has a very dry sense of humour. I have read about people like her.

“How did it go?” says Penny, when I eventually find my way to her room.

“Jolly—I mean, very well,” I say. “I think I’m in.”

“What did I tell you? This place would employ the Boston Strangler if he kept his nails short.”

“Flattery will get you nowhere with me,” I say. “And, talking of flattery, Miss Grimshaw spoke very highly of you.”

“I suppose she was pissed out of her mind, was she? In that mood she loves everybody.”

I like Penny but she can be very cynical sometimes.

“Are you going to take the job?” she says.

“You bet.”

“Right, let’s go out and eat.”

“Go out?”

“Yes. I don’t want you to change your mind.”

“Don’t you have to eat here?”

“I’ve got a free afternoon. Come on, we’ll go down to the village. I feel like a good natter.”

She also feels like four large gin and tonics as I find by the time I am on my second cider—it is strong, too. Not like the stuff Dad gets in at Christimas.

“I feel I should have spent more time at the school,” I say.

“You’ve got plenty of time to do that,” says Penny. “There’s nothing else to see that wouldn’t depress you. Did you notice my room? Like the inside of a coffin only the wood isn’t such good quality.”

“If it’s so awful, why do you stay here?”

“That’s one reason.” Penny indicates a tall, dark-haired man of about thirty who has just come into the bar. “Rex Harrington, the vet. I wouldn’t mind him vetting me, I can tell you.”

The man turns round immediately and I do wish Penny did not have such a loud voice. “Penny, my sweet,” he says coming towards us. “I bumped into Guy a few moments ago. He said you might be popping in for a drink later on?”

“It’s on the cards,” says Penny.

“And your charming companion, I hope?”

“I’ve got to be going back to London,” I say, thinking what sexy eyes the man has. “I’ve already missed the train I was going on.”

“Miss the next one.”

“Rosie, this is Rex,” says Penny. “Rex Harrington, Rosie Dixon.”

“Pleased to meet you,” I say.

“Likewise. What are you both having to drink?”

“I mustn’t have another one,” I say.

“Nonsense. I’ll be offended. What is it, cider?”

Upper class men always seem so sure of themselves. I find it difficult to refuse any suggestion they make. “Just a small one,” I say.

“And a large gin and tonic,” says Penny, holding out her glass.

“Does this pub ever close?” I ask. “It’s half past three now.”

“We operate continental licensing hours around here,” says Penny. “Now we’re in the Common Market it seems the least we can do.”

Rex Harrington is thoughtfully tapping two coins together at the bar and there is something about the way he is looking at my legs that makes me cross them immediately—what a good job he is not looking into my eyes.

“When is the next train?” I ask.

“You might as well wait for the six-thirty, now. It’s a fast train and it will mean that you can have that drink with Guy. It’s a good idea to keep in with the locals.”

I am feeling so exhausted that I don’t argue with her. I suppose it was all the nervous tension I burned up worrying about the interview.