Полная версия:

Gingerbread

COPYRIGHT

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Copyright © Robert Dinsdale 2014

Robert Dinsdale asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007488896

Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780007488919

Version: 2014-07-22

For Kirstie

Who fears the wolf, should not go into the forest.

Belarusian folk saying

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

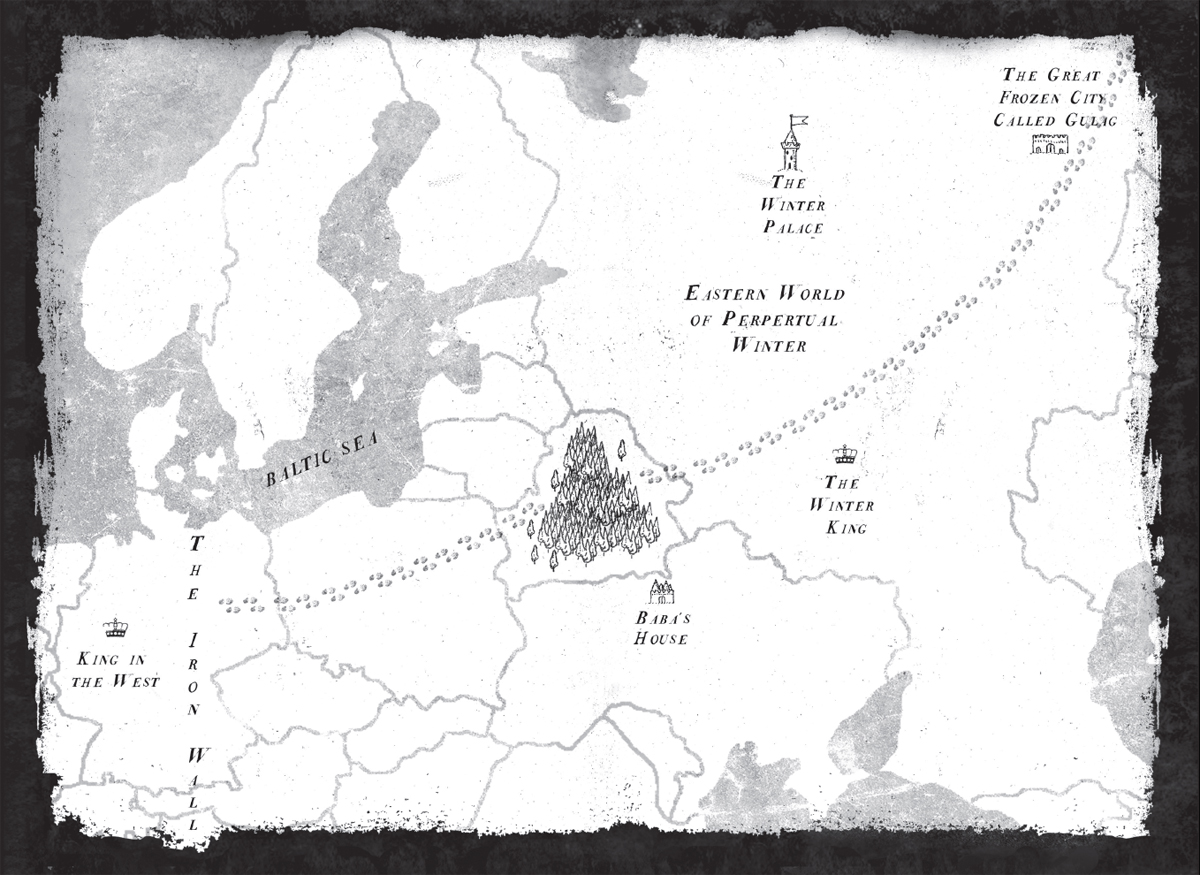

Map

Winter

Summer

Winter Returns

Next Winter

Acknowledgements

A Conversation with Robert Dinsdale

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

When the car comes to a halt, the boy stirs from his slumber. The very first thing he sees is his mama’s face, peering at him through the mirror. She has it angled, so that it doesn’t show the sweeping headlights spreading their colour on the fogged glass, but shows her own features instead. Mama is tall and elegant, with hair at once yellow and grey, and blue eyes just the same as the boy’s. In the thin mirror shard, she traces the dark line under one of those eyes with the tip of a broken fingernail, then spreads it as if she might be able to see more deeply within.

The boy shifts, only to let mama know he is awake. Outside, unseen cars hurtle past.

‘Are we there, mama?’

His mother looks back. She has not been wearing a seatbelt – but, then, the hospital told her she wasn’t to drive the car at all. This, she said as she buckled him in, would have to be their very own secret.

‘Come on, little man. If I remember your Grandfather, he’ll have milk on the stove.’

Mama is first out of the car. Inside, the boy sees her blurred silhouette circle around to help him out. It is not snowing tonight, though mama says it is snowing surely out in the wilds; in the city it is only slush, and that pale snow called sleet. It has fingers of ice and it claws at the boy.

Mama helps him down and crouches to straighten his scarf. Then it is up and over and into the tenement yard. On one side, the road rushes past, with rapids as fearful as any river, while on the other the yard is encased by three sheer walls of brick. Eyes gaze down from every wall, half of them scabbed over by black plastic sheeting, the others alight in a succession of drab oranges and reds.

The tenement is a kind of castle where Grandfather lives. Mama says the boy has been here before, but that was in a time he cannot remember, and might even have been before he was born. Together, they cross the yard, to follow an archway of brick and cement stairs to the levels above. The path goes all the way around the building, like a trail climbing a mountain, and at intervals the boy can peer down to see the car itself dwindling below.

At last, three storeys up, mama stops.

‘Come here,’ she says, and there is something in her voice which makes him cling to her without hesitation.

They are standing before a door of varnished brown, with a threadbare mat on which stand two gleaming ebony boots. The boy is marvelling at these things that seem so old when his mama raps at the door. An interminable time later, the door draws back.

‘Vika,’ comes a low, weathered voice.

The boy’s eyes drift up from the boots, up the length of mama’s body, up the doorjamb broken by hinges. In the doorway, hunches his Grandfather. He seems a shrunken thing, though he is taller than mama, and taller still than the boy. On his head there is little hair, only a fringe of white hanging from behind, and his face is dominated by features that seem too large and out-of-place: a nose with a jagged crest; blue eyes shining, but eye sockets deep and dark. He is wearing a flannel nightgown, burgundy, tied up with a black leather belt, and though his eyes dwell first on mama, they drop second to the boy. He shuffles closer to mama’s legs, and it is only then that he realizes that Grandfather’s eyes have dropped further, to the boots on the mat.

‘My jackboots,’ he says. ‘They’re finished. Bring them, would you, boy?’ Grandfather turns to shuffle inside. ‘Oh, Vika …’

‘We’ll talk soon, papa.’

After mama has gone in, the boy picks up the jackboots and follows.

It is a small place, with a narrow hall and a kitchen at the end. Mama and Grandfather are already in that kitchen, with a pan rattling on the stove, but the boy creeps up quietly, stealing a look at the photographs adorning the walls. In them he sees people he does not know: a mama and a papa and a baby girl; banks of men in uniforms wearing jackboots just the same as those in his hands. He stops to scrutinize the grainy images, and sees long shadows cast at the end of the hall: the malformed shapes of his mama and Grandfather waltzing in the small kitchenette.

‘No,’ Grandfather says, the word stressed by the clatter of pans. ‘I won’t hear it, Vika. You were foolish coming here. It’s giving in. It’s weakness. I didn’t bring you up just to let you give in.’

‘It isn’t weakness, papa. It’s cancer.’

On the tolling of that word, the boy appears in the kitchen door. It is a small room, with a stove in its centre and a ragged countertop running around its wall. Pots are piled up haphazardly in a simple tin sink.

Across the stove, Grandfather’s hand trembles as he lifts a pan. His eyes, desolate, fall on the boy. ‘I made you a hot milk,’ he breathes.

But mama puts an arm around him, and ushers him back into the hall. ‘Come on. I’ll show you your new room.’

There are two bedrooms around a turn in the hallway, and a third little corner with a gas fire and a rocking chair for sitting. Mama ushers him to its furthest end, past yet more photographs of times beyond the boy’s memory.

The room at the end is empty but for a bed with two bunks and a chipped wooden horse standing on the window ledge. As they go through the door, his mama reaches for the light – but no bulb buzzes overhead. Still, she coaxes him in. Setting down the bag from her shoulder, she unrolls a simple set of bedclothes.

‘What do you think?’

‘It isn’t the same as at home.’

‘It’s my home. This is where your mama used to sleep.’

Mama goes to lie on the bed. It is a ridiculous thing to think she might once have slept in it, because even the boy can see she is too big.

‘Mama, look.’

Mama sits up, turns back to the pillow at which the boy is pointing. Where she lay her head, the pillow has kept a neat lock of her hair.

‘Oh, mama,’ whispers the boy.

In two simple strides she is across the room, snatching up the wooden horse from the ledge. She gestures the boy over and, torn between his mama and the hair she left behind, it takes a moment before he complies.

‘This,’ says mama, ‘is my little Russian horse.’

The boy takes it. Once it was painted a brilliant white, with ebony points and a tail of real horsehair, plucked – or so the boy imagines – from the mane of some wild forest mare. Now its paint is dirty and in patches bare, its golden halter a murky brown. The chip above the left eye has given the trinket a look of immeasurable sadness, and the red around its open mouth looks bloody, as if the horse might have come alive in the dead of night and made a feast out of the woodlice who carve their empires in the fringes of the room.

‘It was a present from my mama, and now it’s yours.’

‘Mine?’

‘All yours.’

But the boy blurts out, ‘I don’t want it to be mine. It’s yours, mama. You have to look after it.’

The boy grapples to push it back into her hands. Even so, mama’s hands remain closed.

‘You’ll look after him, and your papa will look after you.’

The boy accepts the Russian horse, feeling its chips beneath his fingers. ‘But who will look after you, mama?’

Mama crouches to plant a single dry kiss on his cheek. Once, her lips were full and wet. ‘Get dressed for bed. I have to speak to your papa.’

After she is gone, the boy sits with the little Russian horse. By turning him in the light from the streetlamps below, he can cast different shadows on the wall: one minute, a friendly forest mare; the next, a monstrous warhorse rising from its forelegs with jaws flashing wild.

He does not get into his nightclothes and he does not climb under the blanket. To do either would mean he would not see mama again until morning, and he knows he must see as much of mama as he can. When he hears voices, he steals back to the bedroom door and out, back past the banks of photographs, back through memories and generations, to the cusp of the kitchen.

His mama’s voice, with its familiar tone of trembling resolve: ‘Promise me, papa.’

‘I promise to care for the boy. Isn’t that enough?’

‘I want to be with my mother.’

‘Vika …’

‘After it’s done, papa, you take me to that place and scatter what’s left of me with her. You listen to me now …’

‘You shouldn’t speak of such things.’

‘Well, what else am I to do, papa?’

His mother has barked the words. Shocked, the boy looks down. His shadow is betraying him, creeping into the kitchen even as he hides himself around the corner.

‘I miss her, papa. On her grave, I haven’t asked you for a single thing, not one, not since the boy was born …’

‘Vika, please …’

‘You do this thing for me, and we’re done. I won’t ask you for anything else.’

‘It has to be there?’

When mama speaks next, the fight is gone from her words. They wither on her tongue. ‘Yes, papa.’

‘Vika,’ Grandfather begins, ‘I promise. I’ll look after the boy. I’ll take you to your mother. And, Vika, I’ll look after you. I’ll hold you when it happens.’

Then comes the most mournful sound in all of the tenement, the city, the world itself: in a little kitchenette, piled high with pans, his mama is sobbing. Her words fray apart, the sounds disintegrate, and into the void comes a wet and sticky cacophony, of syllables, letters and phlegm.

When he peeps around the corner, Grandfather is holding her in an ugly embrace, like a man in a patchwork suit at once too big and too small.

‘And you don’t let him see,’ mama’s words rise out of the wetness. ‘When it happens, you make sure he doesn’t see.’

Strange, to wake in a new home, with new sounds and new smells in the night. The tenement has a hundred different halls, and the footsteps that fall in them echo through all of the building – so that, when he closes his eyes, he can hear a constant scratch and tap, as of a kidnapper at his window.

Mama has her own room, across the hall in the place where Grandfather used to sleep. Grandfather has a place by the gas fire, in a rocking chair heaped high with blankets and the jackboots at his side. It is here that the boy finds him every morning, and here that they sit, each with a hot milk and oats. New houses have new rules, and the boy must not leave the alcove while Grandfather takes mama her medicines and helps with her morning ablutions. The boy is not allowed to see his mama in the mornings, but he is allowed to spend every second with her after his schooling is finished.

This morning, he is lying in the covers with the old bunk beams above, when the door opens with an unfamiliar creak. There is an unfamiliar tread, unfamiliar breath – and, though he wants it to be mama, it is Grandfather who tramps into the room.

‘Come on, boy. Time for school.’

The boy scrabbles up. ‘Is mama …’

‘She’s only resting.’

That is enough to quell the fluttering in the boy’s gut, so he rolls out of the covers and follows Grandfather. The old man is retreating already down the hall, past the photographs of the long ago, when everything was black and white. The boy hesitates, eyes drawn inexorably to the doorway across the hall. Then Grandfather calls and he follows.

In the kitchen, he studies Grandfather as they eat. Once upon a time, Grandfather was only a story. The boy lived with his mama and only his mama in a house near the school, and in the days he learnt lessons and played with the boy named Yuri, and in the nights he came home and sat with mama with dinner on their laps. Now, Grandfather is real. He has a face like a mountain in the shape of his mother, and ears that hang low.

‘What was mama like when she was little?’

Grandfather pitches forward, breaking into a smile that takes over all of his face. What big teeth he has, thinks the boy.

‘She was,’ he beams, ‘a … nuisance!’

Then Grandfather’s hands are all over him, in the pits of his arms and the dimples on his side, and he squirms and he shrills, until Grandfather has to tell him, ‘You’ll wake your mama. Go on, boy, up and get dressed.’

It used to be that mama walked him to the school gates, but the tenement is far from the school, almost on the edge of the city, where hills and the stark line of pines can be seen through the towers and factory yards, so today they must take a bus. The boy asks, ‘Why can’t we drive the car?’ But Grandfather isn’t allowed to drive, so instead they wait in the slush at the side of the road until a bus trundles into view.

As he puts his foot on the step to go in, he thinks of mama, alone in the tenement like a princess locked in her tower. He halts, so that the people clustered behind him bark and mutter oaths.

From the bus, Grandfather says, ‘What is it, boy?’

‘It’s mama.’

‘She’ll be okay. She’s resting.’

‘I don’t want her to be on her own. Not when …’

Grandfather’s face softens, as if the muscles bunching him tight have all gone to sleep. ‘That isn’t for a long time yet.’

The boy nods, pretending that he believes – because even pretending and knowing you’re pretending is better than not pretending at all.

He settles into a seat beside Grandfather and, as the bus gutters off, cranes back to see the tenement retreating through the condensation.

Sitting next to Grandfather is not the same thing as sitting next to a stranger, because in his head he knows that Grandfather was once mama’s papa, and that, once upon a while, Grandfather took mama to school and maybe even sat on a bus just the same as this. Yet, knowing a man from photographs is not the same as sitting next to him and hearing his chest move up and down, or seeing the ridges on the backs of his hands. Every time Grandfather catches him watching, the old man grins. Then the boy is shamefaced and must bury his head again. Once the shame has evaporated, the boy can look back; then Grandfather catches him again, grins again, and once even puts a hand on the boy’s hair and rubs it in the way mama sometimes does.

‘I bet you’re wondering about your old papa, aren’t you?’

The boy shakes his head fiercely. It is a terrible thing not to know which is wrong and which is right.

‘I’m sure you’ve heard stories.’

That word tolls as strongly as any other, and he looks up. ‘Stories?’

‘Things your mama’s told you, about her old papa.’

‘Oh …’

‘No?’

‘I thought you meant other sorts of stories.’

They sit in silence, as the bus chokes through the lights of a mangled intersection.

‘You like stories?’

The boy nods.

‘Then maybe we’ll have a story tonight. How does that sound?’

The boy nods his head, vigorously. It is a good thing to know which is wrong and which is right. ‘Do you know lots of stories?’

Before Grandfather can elaborate, the bus stutters to a stop, the driver barks out a single word – schoolhouse! – and the boy must scramble to get off.

‘Are you coming, papa?’

It seems that Grandfather will take him only to the edge of the bus, but there must be a pleading look in the boy’s eyes, because then he comes down to the slushy roadside and, with one hand in the small of his back, accompanies the boy to the schoolhouse gates. There are other children here, and other mamas and papas, but none so old and out of place as Grandfather.

He looks for faces he knows, and finally finds one: the boy Yuri, who does not run with the hordes but paces the school fence every morning and afternoon, muttering to himself as he dreams. Yuri is good at drawing and good at stories, but he is not good at being a little boy like all of the rest. He is about to go to him when a figure, the vulpine woman who does typing in the headmistress’s study, appears on the schoolhouse steps and begins clanging a bell.

‘Will you come, papa, when school’s done?’

Grandfather has a sad look in his eyes, which makes the boy remember his promise.

‘Tonight and every night, boy.’

‘And you’ll look after mama?’

Grandfather nods.

Next come words the boy knows he should not have heard. ‘And hold her, when it’s time?’

Grandfather opens his leathery lips to speak, but the words are stillborn. ‘Off with you, boy,’ he finally says.

The boy turns and scurries into school.

In lessons, Mr Navitski asks him about his mama and he lies and says his mama’s getting better, which will stop them asking and, in a strange way, make it so he doesn’t have to lie again. Mr Navitski is a kind man. He has black hair in tight curls that recede from his forehead to leave a devil’s peak, but grow wild along the back of his neck as if his whole pate is slowly stealing down to his shoulders. He wears a shirt and braces and tie, and big black boots for riding his motorcycle through town.

In the morning there is drawing, and he makes a drawing of Grandfather: big wrinkled mask and drooping ears, but eyes as big as silver coins and dimples at the points of the greatest smile. Yuri, who doesn’t say a thing, works up a picture of a giant from a folk tale – and when Mr Navitski lines them up for the class to see, the boy is bewildered to find that Yuri’s giant and his Grandfather have the same sackcloth face, the same butchered ears, the same bald pate and fringe of white hair. The only difference, he decides, is in the eyes, where simple flecks of a pencil betray great kindness in Grandfather and great malice in the giant.

In the afternoon it is history. This means real stories of things that really happened, and when Mr Navitski explains that, one day, everything that happens in the world will be a history, it thrills the boy – because this means he himself might one day be the hero of a story. He looks at Yuri sitting at the next desk along and wonders: could Yuri be the hero of a story too? He is, he decides, more like the hero’s little brother, or the stable-hand who helps the hero onto his horse before he rides off into battle.

On the board, in crumbling white chalk, Mr Navitski writes down dates. ‘Who can tell me,’ he begins, ‘what country they were born in?’

Hands fly up. The boy ventures his too late, and isn’t asked, even though he’s known the answer all along. This kingdom of theirs is called Belarus.

‘And who can tell me,’ Mr Navitski goes on, ‘what country their mamas and papas were born in?’

More hands shoot up. Some cry out without being asked: Belarus! Because the answer is obvious, and the prize will go to whoever gets there most swiftly.

But Mr Navitski shakes his head. ‘Trick question!’ he beams. ‘This country wasn’t always Belarus, was it?’

Yuri shakes his head so fiercely it draws Mr Navitski’s eye. ‘What country was it, Yuri?’

Yuri can only shake his head again, admitting that he doesn’t know.

‘Well, Yuri’s half got it right. Because once, not so very long ago – though long ago might mean a different thing to you little things – Belarus wasn’t truly a country at all. In just a few short years, it was part of many other countries and had different names: Poland, Germany, a great, sprawling land called the Soviet Union. And before that it was part of the Russias. Who knows what the Russias are?’

Though Yuri throws his hand up, this time Mr Navitski knows not to ask.

‘It’s an empire,’ says the boy.

‘Well, half-right again … Russia was a nation, with emperors called tsars, and it stretched all the way from the farthest east to the forests where we live today. What’s special about those forests?’

Now there is silence, all across the class.

‘Well, I’ll tell you,’ he says. ‘Once, all of the world was covered in forests. But, slowly, over the years, those forests were driven back – by people just like us. They chopped them down to make timber, and burned them back to make farms. But this little corner of the world where we live is very special. Because half our country is covered in forests that have never been chopped or cut back. The oaks in those forests are hundreds of years old. They’ve grown wizened and wise. And those forests have seen it all: the Russias, and Poland, and Germany, emperors and kings and too many wars. Those trees would tell some stories, if only they could speak!

‘And the truly amazing thing about Belarus is that, no matter how many times an empire came and made us their own, no matter how many soldiers and armies tramped through this little country and carved it up … not once, in the whole of history, have those forests ever been conquered. Those forests will always be, and have always been, ruled by no man or beast. And that makes them the wildest, most free place on Earth …’

The boy looks down. Yuri has been desperately drawing trees on his piece of paper. In between, he scrawls words: wild … free … Belarus. He presses down hard, promptly breaks the tip of his pencil, and looks up with aggrieved eyes – but the boy just keeps on staring at the page.

At the end of the day, Grandfather is waiting. As the boy hurries to meet him, something settles in his stomach: a promise has been fulfilled.

‘Mama?’ he asks, before he even says hello.

‘She’s …’

The boy pulls back from Grandfather’s touch, shrinking at eyes that glimmer with such goodness.

‘… waiting for you,’ Grandfather goes on. ‘She made you her kapusta.’

To get back to the tenement, they have to take another bus. This time, it feels better to sit next to Grandfather, which is foolish because the difference is only a few short hours. Now he can ask Grandfather questions, and Grandfather will answer: how long have you lived in the tenement? How old are you, papa, and what was it like so long ago? And, most important of all, what kind of story will it be tonight, papa, when we have our story?