Полная версия:

The Spy Quartet: An Expensive Place to Die, Spy Story, Yesterday’s Spy, Twinkle Twinkle Little Spy

LEN DEIGHTON

The Spy Quartet

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

An Expensive Place to Die first published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape Ltd 1967

Spy Story first published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape Ltd 1974

Yesterday’s Spy first published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape Ltd 1975

Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Spy first published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape Ltd 1976

An Expensive Place to Die copyright © Len Deighton 1967

Spy Story copyright © Len Deighton 1974

Yesterday’s Spy copyright © Len Deighton 1975

Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Spy copyright © Len Deighton 1976

Introductions copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2012

Cover designer’s notes © Arnold Schwartzman 2012

Cover design and photography © Arnold Schwartzman 2012

E-bundle cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of these works.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

These novels are entirely works of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in them are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007458349, 9780007458363, 9780007458370, 9780007458356

Ebook Edition © January 2015 ISBN: 9780008116224

Version: 2017-08-18

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

An Expensive Place to Die

Spy Story

Yesterday’s Spy

Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Spy

About the Author

By Len Deighton

About the Publisher

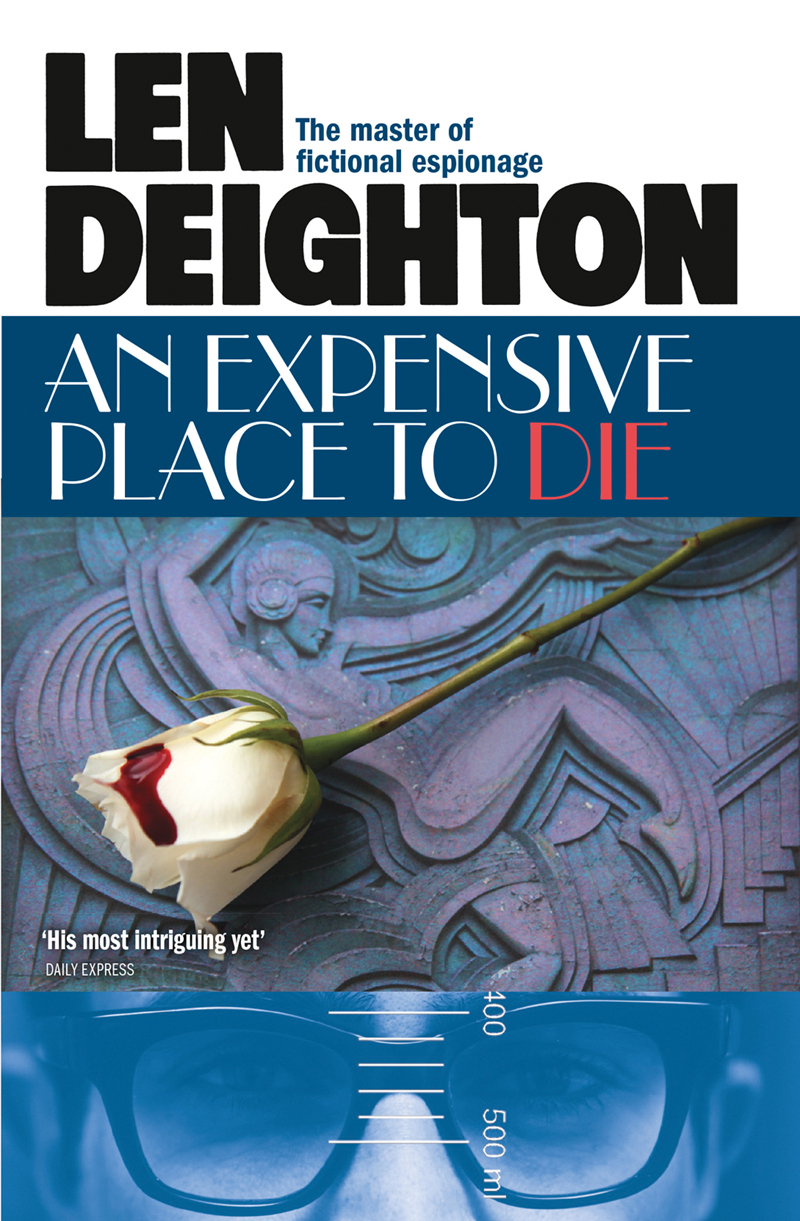

Cover designer’s note

On a visit to Paris to produce a book on that charming city’s Art Deco architecture, my first stop was to locate the Folies Bergère, the legendary music hall where music would become just one of the many entertainments on offer to patrons. It was the author’s suggestion that I introduce an image that evoked ‘Gay Paree’. I believed that this image would fit the bill perfectly, and indeed it does. The dancing figure of the woman very much symbolizes one of the femmes fatales plying their trade so artfully for Monsieur Datt, and the multitude of swirling patterns behind her lead the eye on many a confusing journey – just like those endured by our intrepid hero.

I was also inspired by the book’s inclusion of a quotation from the poem ‘May’:

‘… If she is not a rose, a rose all white,

Then she must be redder than the red of blood.’

A rose has come to symbolize many things in the arts, and here the contrast between the virginal and the sinful taint of blood is particularly apposite. The juxtaposition of the blood-stained rose over the Folies facade provided me with the key design element.

On each front cover of this latest quartet, I have placed a photograph of the eyes of the bespectacled unnamed spy, in this instance overlaid with calibration marks from a hypodermic syringe. Why a syringe? Well, that will become all too apparent as you delve deeper into the seedy world of An Expensive Place to Die.

A final touch to the front cover was the choice of a typeface that would present an elegant facade beneath which the elements of corruption would appear. The reason for my use of red for the final word is three-fold: it helps to draw attention to the blood on the rose; it creates the tricolour of the French flag; and it offers a cheeky sense of melodrama – humour is always important, especially in the works of this author.

Readers who have been faithfully building their collection of these reissues will by now have become familiar with my use of a linking motif on the spines of the books. Being the final foursome in the entire series of reissues, and books in which violence is never too far away, I thought it a good idea to ‘go out with a bang’, as it were. This quartet’s spines accordingly display a different handgun, as mentioned in each of the books’ texts. The example here is a 6.35mm Mauser automatic, which was an antique even during the period of this story.

Another recurring feature in this quartet, to be found within each back cover’s photographic montage, is a pair of ‘our hero’s’ glasses, which look suspiciously like those worn by ‘Harry Palmer’ in The Ipcress File and other outings...

For this book’s montage, in order to evoke communist China’s involvement in the plot, I included a bust of Mao that I purchased some time ago in Shanghai. Like many of my objets from another time, it has found a new life helping to tell a story that the Chairman no doubt would have frowned upon.

A souvenir ashtray featuring the Eiffel Tower becomes the receptacle for a lipstick-traced remnant of one of our hero’s Gauloise cigarettes, plus a Parisian Gendarme’s badge. Further pieces of ephemera are a vintage Folies Bergère programme plus a pair of Paris postcards. The top hat from a Monopoly set is a nod to the elite of Parisian society who are caught in Monsieur Datt’s web, and the dice and ace of spades card tell us that to enter his world is a gamble, which can lead to death. Lastly, the quarter-inch magnetic tape underneath the top hat is of a recording that I produced of Mick Jagger promoting one of The Rolling Stones albums for Radio Luxembourg!

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

Hollywood 2012

LEN DEIGHTON

An Expensive Place to Die

Do not disturb the President of the Republic

except in the case of world war.

Instructions for night duty officers

at the Élysée Palace

You should never beat a woman,

not even with a flower.

The Prophet Mohammed

Dying in Paris is a terribly expensive

business for a foreigner.

Oscar Wilde

The poem ‘May’ quoted here is from Twentieth Century Chinese Poetry, translated by Kai-yu Hsu (copyright © Kai-yu Hsu 1963) and reprinted by permission of Doubleday & Co. Inc., New York

Contents

Cover

Cover designer’s note

Title Page

Epigraph

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Footnotes

Introduction

France beckons to every lonely misfit, and most novelists answer to that description at some time or another. Many authors have responded to France’s call with enthusiasm; notably during those years between the two world wars when the exchange rates favoured those with US dollars, and Prohibition at home made the noble vintages of France irresistible. But most of those writers were prudent. Writing primarily for English-speaking readers they wrote stories about English-speaking people. Most of those stories were vaguely autobiographical ones about the wealthy English and American visitors with whom the writers fraternized. France provided the mountains and the Mediterranean but the French people in the stories were mostly waiters.

Many of the resulting books were dazzling; some became classics but many of the stories could have taken place in Gloucestershire or Long Island. This was a practical restraint, but writing about France without depicting French people (however inaccurate or untypical the characterizations might be) is like eating a chocolate bar without first removing the wrapper. I am not prudent. I wanted to tell my story with French men and women playing major roles.

It was this need to bring French people into An Expensive Place to Die that led to my including some chapters in the third person. This gave me a chance to show their thoughts and motivation and an opportunity to have action beyond that of the first person. This was not a planned device, it came naturally to the telling of the story and no one criticized it.

No doubt every writer has their own method of writing and this is something that writers enjoy talking about. Most important is whether to write after making a careful plan or to simply invent each new chapter as it comes. Many writers have told me that they don’t know what the end of their books will be when they are writing the first page. The argument against this is the uncertainty that comes of consigning the plot to the vagaries of the writer’s day-to-day temperament. My experience is that there comes a stage in the planning when it is best to start writing and leave some room to develop your characters. Whatever method is chosen, some element of your story is likely to assume an importance beyond your plan. In XPD a character named Charles Stein became that sort of element. He wrestled to take control of my story and nearly did so. Looking back on it, the book was much enhanced by him. For An Expensive Place to Die it was Paris that took on an unplanned importance, and this gives the book an atmosphere rather different to all the other books I have written.

I was a teenager when I first went to Paris. It was not ‘warm and gay’ as the Hammerstein lyric recalled; rather it was ‘old and grey’ as in the lyric that Sinatra was crooning at that time. The war was scarcely ended and I stepped from the train into a dense aroma of Gauloises and garlic. I found myself alone and without contacts standing on the noisy concourse of the Gare du Nord. Packed tight, there were beggars, whores and black-market traders all plying their trades with appropriate subtlety. Heavily burdened infantrymen displayed the silence of the weary while polished and blancoed military police patrols sifted continually through the multitude. My parents had only agreed to this expedition because someone was to meet me and take care of me. That friend was posted away at short notice and I was left to my own devices. Someone put a card into my hand and I plodded along, suitcase in hand, to Place Blanche, a seedy district adjacent to Montmartre. Using the advertisement card, I found a tiny attic room in an old, cheap, threadbare hotel near the Moulin Rouge.

It was all exactly like the little room in which Jean Gabin fought off the flics in that wonderful old film Le Jour se Lêve. All that night I waited for the ‘daybreak’ as I had waited for Santa Claus to arrive on so many Christmas mornings. When light came through the shabby curtains I looked out of the window at the roofs of Paris. This remains one of the most memorable moments of my long, eventful and happy life. I was a teenager, and entirely unsupervised, with this great foreign city laid at my feet. I could scarcely believe my good fortune. I tramped around the city; stood alone at the tomb of Napoleon and inspected the burned-out German tanks that the French were in no hurry to clear away. The fighting had ended but the smell of war lingered. I walked all the way to the Etoile and then back across town to the Place Bastille, only to be sadly disappointed that the grim old prison was no longer there. The Folies Bergère is just for tourists, the concierge at the hotel told me; the Concert Mayol is far more risqué and the girls far, far more naked. I went to the Concert Mayol. I went to the Louvre, where they also had naked girls, to Notre Dame and to that most spectacular of Paris sights – the Sainte Chapelle. I climbed the steep, slippery, and seemingly unending iron steps to get to the top of the Eiffel Tower, and was spattered with red lead primer paint as I passed workers restoring it to good condition.

Although I was in civilian clothes, my youth and London accent caused me to be mistaken for a soldier and I capitalized on this by eating in the military facilities such as the Montgomery Club near the Place de la Concorde. In some places I was eyed with suspicion and twice I was detained on suspicion of being an army deserter. I soon made sure I carried my passport everywhere I went. I must have walked many miles during that time in Paris and by saving my money I was able to afford a lunch at the renowned Tour d’Argent, which had resumed its production of the famous roast duck, prepared at the tableside in a massive silver press.

After that first visit, I returned to Paris many times. For short periods I lived there in varying degrees of comfort. My wife’s parents enjoyed a lovely home there and we relished their hospitality. The idea of writing about this Paris I discovered never went away. I knew several fashion photographers and in the early 1960s I started notes for a book using as a background the Paris collections. I continued my lengthy stay there but I didn’t continue with this project. I also abandoned a story about a symphony orchestra because I didn’t know enough about music and musicians. Finally I met a Paris policeman who wanted to practise his English and I knew I was going to write An Expensive Place to Die.

Together with my family I have lived in many countries, but I never became one of the dedicated exiles who cluster in the sunshine and snow. Perhaps the France I depict in An Expensive Place to Die is not a land you recognize. Yet this is what France, or more particularly Paris, seemed like back in the sixties when I lived there and wrote this book.

It was the chance introduction to a detective serving with the police judiciaire that gave me the chance to write about the underside of Paris. This friend served in the brigade mondaine, which is the quaint title the French give to what in London was called the vice squad. My policeman knew everything and everyone. People high and low, people in bars and those in exclusive clubs knew him and so did those who went to sleep on the pavement, hugging smelly ventilation grills for the sake of the warmth. In late evening, hundreds of big trucks brought fresh produce into the old market area, and not all the drivers curled up in their cab with a blanket and a bottle of beer. Around the market whole streets of bars and brothels came to life at midnight and plain-clothes policemen, such as my friend, were an inevitable addition to the cast. Muscular doormen and girls with too much make-up greeted him like an old friend. He showed me the flea markets where stolen goods sometimes came to light. He showed me establishments in the swanky arrondissements that do not feature in any tourist guidebooks. It is ‘down these mean streets’ that a fiction writer can venture protected by the armour of disguise that all storytellers wear. I kept close to his side and kept my mouth shut as we walked his beat. Without his unstinting help and good-natured guidance (and did I say protection?) An Expensive Place to Die would have been a different, and rather more conventional, book.

It happens like that sometimes. You encounter a promising source and suddenly a torrent of information comes pouring down all over you. Now the problem becomes knowing where to stop. Research is always more fun than writing and there is always a temptation to go on with it for ever. I enjoy using foreign locations in my stories but feel I should carefully absorb the places I write about; live in them long enough to meet my neighbours, buy from the local shops, sit around in the local cafes and suffer the bus services and the Metro. For some books I went beyond that. My children attended local schools and we almost became natives. Only probing beyond the tourist trails will give a writer the environment in which convincing characters can roam. In An Expensive Place to Die I probed, but the Paris into which I dug was somewhat bleak. Looking back now, perhaps a more generous portion of the glamour of that much-maligned city would have given my story more optimism.

But there was a mysterious epilogue to An Expensive Place to Die. On 24th April 1967 the New York Times carried a story concerning two Russian nationals; both identified by the US Government as officers of the KGB. At Kennedy International Airport they boarded Air France Flight 702 scheduled to depart for Paris at 7.00pm. Ten minutes before the flight was due to leave a man who identified himself as an FBI agent went to Gate 29, handed an Air France official a package and asked him to give it to one of the Russians. Curious about the last-minute arrival of the package, the chief stewardess, Marguerite Switon, gave it to the pilot, Michel Vachey. By this time he was moving his plane from the gate to the runway for take-off.

Still at the controls, the pilot opened the package and found inside a copy of An Expensive Place to Die. It also contained a small dossier of replica documents and maps that were tucked inside the book. Here were official-looking papers signed by high officials and marked ‘Top Secret’. (This dossier had in fact been designed by Ray Hawkey as a supplement to the story; Ray designed the covers of many of my books, and also some similarly fine publicity material for books such as SS-GB.) Vachey was alarmed. He asked the tower for permission to taxi back to Gate 29, to which Air France’s station manager was summoned.

According to the New York Times article the plane was delayed while FBI officials examined the papers and took guidance via several phone calls to FBI headquarters in Washington. At 9.30pm the Air France flight took off for Paris. This strange story was taken up by other papers including The New York Daily News.

It sounds like a successful publicity stunt but Walter Minton, a good friend as well as being president of Putnam’s, my New York publishing house, denied all knowledge of these minor dramas. In London my publishers knew nothing about ‘stunts’ and neither did my good friend Ray Hawkey. So what is the real story behind it? I am still hoping that someone will tell me.

It was not the only time these documents would interest the Russians. I learnt that a Soviet official in Canada paid money for the dossier believing it to be secret material. A year or two later I was told that it all happened at a time when the Russians were particularly touchy about Chinese espionage. They wondered whether someone with inside knowledge about planted information had provided to me the plot of An Expensive Place to Die.

Len Deighton, 2012

1

The birds flew around for nothing but the hell of it. It was that sort of day: a trailer for the coming summer. Some birds flew in neat disciplined formations, some in ragged mobs, and higher, much higher, flew the loner who didn’t like corporate decisions.

I turned away from the window. My visitor from the Embassy was still complaining.

‘Paris lives in the past,’ said the courier scornfully. ‘Manet is at the opera and Degas at the ballet. Escoffier cooks while Eiffel builds, lyrics by Dumas, music by Offenbach. Oo-là-là our Paree is gay, monsieur, and our private rooms discreet, our coaches call at three, monsieur, and Schlieffen has no plans.’

‘They’re not all like that,’ I said. Some birds hovered near the window deciding whether to eat the seed I’d scattered on the window-sill.

‘All the ones I meet are,’ said the courier. He too stopped looking across the humpty-backed rooftops, and as he turned away from the window he noticed a patch of white plaster on his sleeve. He brushed it petulantly as though Paris was trying to get at him. He pulled at his waistcoat – a natty affair with wide lapels – and then picked at the seat of the chair before sitting down. Now that he’d moved away from the window the birds returned, and began fighting over the seed that I had put there.

I pushed the coffee pot to him. ‘Real coffee,’ he said. ‘The French seem to drink only instant coffee nowadays.’ Thus reassured of my decorum he unlocked the briefcase that rested upon his knees. It was a large black case and contained reams of reports. One of them he passed across to me.

‘Read it while I’m here. I can’t leave it.’

‘It’s secret?’

‘No, our document copier has gone wrong and it’s the only one I have.’

I read it. It was a ‘stage report’ of no importance. I passed it back. ‘It’s a lot of rubbish,’ I said. ‘I’m sorry you have to come all the way over here with this sort of junk.’

He shrugged. ‘It gets me out of the office. Anyway it wouldn’t do to have people like you in and out of the Embassy all the time.’ He was new, this courier. They all started like him. Tough, beady-eyed young men anxious to prove how efficient they can be. Anxious too to demonstrate that Paris could have no attraction for them. A near-by clock chimed two P.M. and that disturbed the birds.

‘Romantic,’ he said. ‘I don’t know what’s romantic about Paris except couples kissing on the street because the city’s so overcrowded that they have nowhere else to go.’ He finished his coffee. ‘It’s terribly good coffee,’ he said. ‘Dining out tonight?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘With your artist friend Byrd?’

I gave him the sort of glance that Englishmen reserve for other Englishmen. He twitched with embarrassment. ‘Look here,’ he said, ‘don’t think for a moment … I mean … we don’t have you … that is …’

‘Don’t start handing out indemnities,’ I said. ‘Of course I am under surveillance.’

‘I remembered your saying that you always had dinner with Byrd the artist on Mondays. I noticed the Skira art book set aside on the table. I guessed you were returning it to him.’