Полная версия:

The Harry Palmer Quartet

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

The Ipcress File first published in Great Britain by Hodder & Stoughton 1962

Horse Under Water first published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape 1963

Funeral in Berlin first published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape 1964

Billion-Dollar Brain first published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape 1966

Copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 1962, 1963, 1964, 1966

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2009

Cover design and photography © Arnold Schwartzman 2009

E-bundle cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2013

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780586026199, 9780586044315, 9780586045800, 9780586044285

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2013 ISBN 9780007531479

Version: 2018-11-27

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Contents

Cover

Copyright

The Ipcress File

Horse Under Water

Funeral in Berlin

Billion Dollar Brain

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

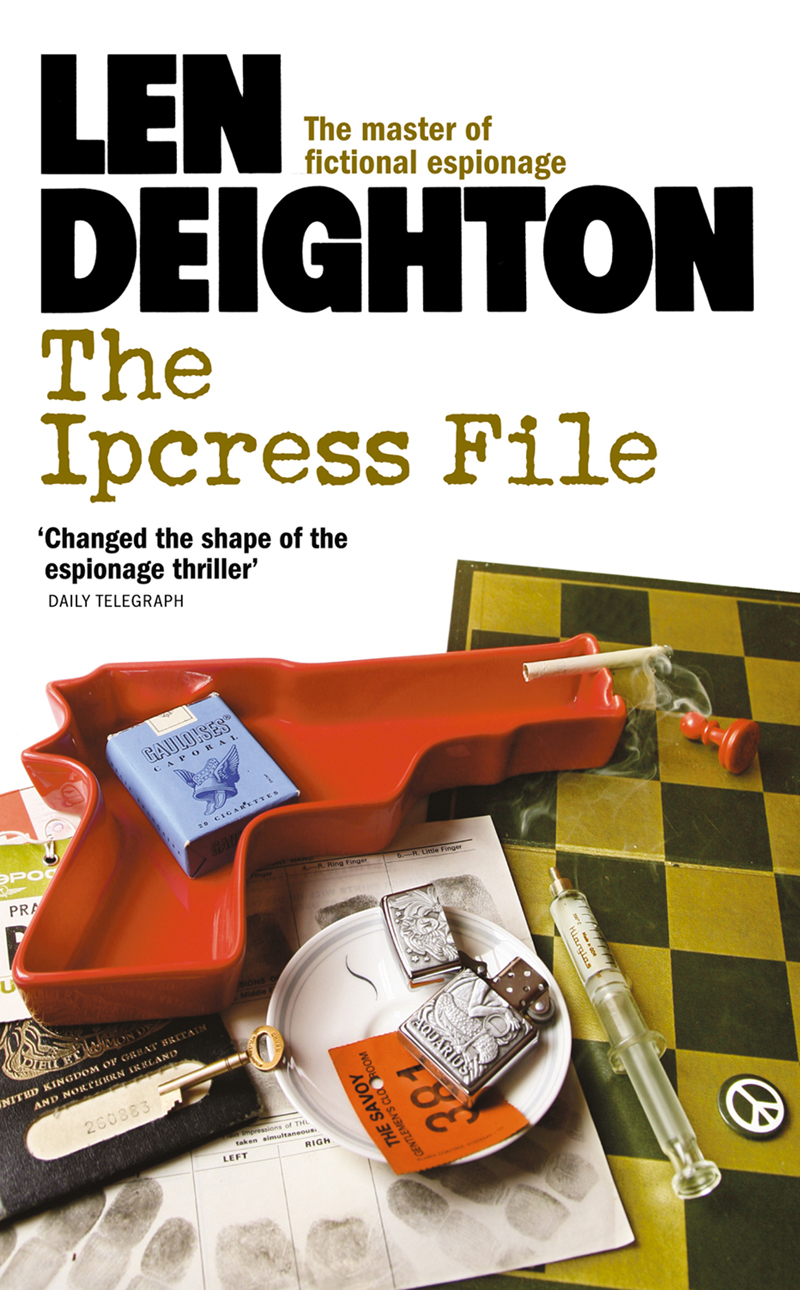

Cover Designer’s Note

The great challenge I faced when asked to produce the covers for new editions of Len Deighton’s books was the existence of the brilliant designs conceived by Ray Hawkey for the original editions.

However, having arrived at a concept, part of the joy I derived in approaching this challenge was the quest to locate the various props which the author had so beautifully detailed in his texts. Deighton has likened a spy story to a game of chess, which led me to transpose the pieces on a chess board with some of the relevant objects specified in each book. I carried this notion throughout the entire quartet of books.

Since smoking was so much part of our culture during the Cold War era, I also set about gathering tobacco-related paraphernalia.

Each chapter of The Ipcress File opens with its Gauloises-smoking protagonist’s horoscope, so discovering an Aquarius cigarette lighter was a great coup. Finding a Gauloises cigarette packet, designed by Marcel Jacno in 1936, became a more difficult proposition. However, after much searching, I eventually found one via the Internet!

Serendipity sometimes plays an important part in the design process. In seeking an appropriate ashtray, to carry through the ‘smoking’ theme, I accidentally came across a unique piece shaped like a hand gun, so I aimed it at a red chess pawn, which represents Ipcress’s ‘Red’ Cold War antagonist.

The image of the gun pays homage to the original Hawkey-designed Ipcress jacket. I further retained the wooden type font logotype originated by him.

One of my long-time hobbies has been collecting cigarette cards. I was fortunate to find some appropriate images among my personal trove to illustrate the back cover, and these are accompanied by examples of military insignia gathered during my National Service days served in Cold War Korea!

Len Deighton and I shared a great affection for London’s Savoy Hotel. My father had served as a waiter there in the 1930s so I have a number of pieces of memorabilia from the Savoy, including the saucer and the cloakroom ticket depicted on the cover.

I was thrilled to locate the ‘Made in GDR’ syringe in Latvia, of all places. Closer to home, I have kept all my past British passports, together with most of my boarding passes and baggage labels. The Chubb key and the CND badge—which today has become a fashion accessory—came from other locations around the UK. The 1960s postage stamp on the spine of the cover commemorates the former Soviet spy, Richard Sorge.

During the 1970s, while designing a supplement series for the London Sunday Times, I needed a set of fingerprints to illustrate a specific article, so I persuaded the duty sergeant at my local police station to take mine, which are here given a new public airing!

I photographed the cover set-up using natural daylight, with my Canon OS 5D digital camera.

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

LEN DEIGHTON

The Ipcress File

Epigraph

And now I will unclasp a secret book, And to your quick-conceiving discontents, I’ll read you matter deep and dangerous.

Henry IV

Though it must be said that every species of birds has a manner peculiar to itself, yet there is somewhat in most genera at least that at first sight discriminates them, and enables a judicious observer to pronounce upon them with some certainty.

Gilbert White, 1778

Contents

Cover

Cover Designer’s Note

Title Page

Epigraph

Introduction

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Epilogue

Appendix

Introduction

The Ipcress File was my first attempt to write a book. I was a commercial artist, or ‘illustrator’ as we are now called. I had never been a journalist or reporter of any kind so I was unaware of how long writing a book was likely to take. Knowing the size of the task is a deterrent for many professional writers, which is why they defer their ambitions often until it is too late. Being unaware of what’s ahead can be an advantage. It shines a green light for everything from enlisting in the Foreign Legion to getting married.

So I stumbled into writing this book with a happy optimism that ignorance provides. Was it a depiction of myself? Well, who else did I have? After completing two and a half years of military service I had been, for three years, a student at St. Martin’s School of Art in Charing Cross Road. I am a Londoner. I grew up in Marylebone and once art school started I rented a tiny grubby room around the corner from the art school. This cut my travelling time back to five minutes. I grew to know Soho very well indeed. I knew it by day and by night. I was on hello, how are you? terms with the ‘ladies’, the restaurateurs, the gangsters and the bent coppers. When, after some years as an illustrator, I wrote The Ipcress File much of its description of Soho was the observed life of an art student resident there.

After three years postgraduate study at the Royal College of Art I celebrated by impulsively applying for a job as flight attendant with British Overseas Airways. In those days this provided three or four days stop-over at the end of each short leg. I spent enough time in Hong Kong, Cairo, Nairobi, Beirut and Tokyo to make good and lasting friendships there. When I became an author, these background experiences of foreign people and places proved of lasting benefit.

I don’t know why or how I came to writing books. I had always been a dedicated reader; obsessional is perhaps the better word. At school, having proved to be a total dud at any form of sport – and most other things – I read every book in sight. There was no system to my reading, nor even a pattern of selection. I remember reading Plato’s The Republic with the same keen attention and superficial understanding as I read Chandler’s The Big Sleep and H.G. Wells’ The Outline of History and both volumes of The Letters of Gertrude Bell. I filled notebooks as I encountered ideas and opinions that were new to me, and I vividly remember how excited I was to discover that The Oxford Universal Dictionary incorporated thousands of quotations from the greatest of great writers.

So I wasn’t taking myself too seriously when, as a holiday diversion, I took a school exercise book and a fountain pen, and started this story. Knowing no other style I did it as though I was writing a letter to an old, intimate and trusted friend. I immediately fell into the first person style without knowing much about the literary alternatives.

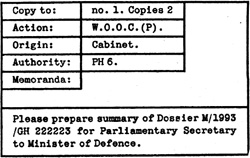

My memory has always been unreliable, as my wife Ysabele regularly points out to me, but I am convinced that this first book was influenced by my time as the art director of an ultra-smart London advertising agency. I spent my days surrounded by highly educated, witty young men who had been at Eton together. We relaxed in leather armchairs in their exclusive Pall Mall clubs. We exchanged barbed compliments and jocular abuse. They were kind to me, and generous, and I enjoyed it immensely. Later, when I created WOOC(P), the intelligence service offices depicted here, I took the social atmosphere of that sleek and shiny agency and inserted it into some ramshackle offices that I once rented in Charlotte Street.

Using the first person narrative enabled me to tell the story in the distorted way that subjective memory provides. The hero does not tell the exact truth; none of the characters tell the exact truth. I don’t mean that they tell the blatant self-serving lies that politicians do, I mean that their memory tilts towards justification and self-regard. What happens in The Ipcress File (and in all my other first-person stories) is found somewhere in the uncertainty of contradiction. In navigation, the triangle where three lines of reference fail to intersect is call a ‘cocked hat’. My stories are intended to offer no more precision than that. I want the books to provoke different reactions from different readers (as even history must do to some extent).

Publication of The Ipcress File coincided with the arrival of the first of the James Bond films. My book was given very generous reviews and more than one of my friends was moved to confide that the critics were using me as a blunt instrument to batter Ian Fleming about the head. Even before publication day, I was taken by Godfrey Smith (a senior figure at The Daily Express newspaper) to lunch at the Savoy Grill. We discussed serial rights. The next day I went in my battered old VW Beetle to Pinewood Film Studios and lunch with the unforgettable and in every way astonishing Harry Saltzman. He had co-produced Dr. No, which was getting widespread publicity, and had decided that The Ipcress File and its unnamed hero could provide a counterweight to the Bond series. On the way to Pinewood my car phone brought a request for an interview with Newsweek and there were similar requests from publications in Paris and New York. It was difficult to believe this was all really happening; illustrators were never treated like this. Never! I was nervously unbelieving, and constantly ready to wake up from this frantic dream. Between meetings and interviews I continued my work as a freelance illustrator. My friends delicately ignored my Jekyll and Hyde life, and so did the clients to whom I delivered my drawings. I didn’t feel like a writer, I felt like an impostor. I didn’t have those intense literary ambitions that writers are supposed to have while they languish in a cobwebbed garret.

Publication proved that I wasn’t the only one surprised by the book’s success. Despite the serialization and the entire hullabaloo, Hodder and Stoughton resolutely restricted their print order to 4,000 books. These were sold out in a couple of days. Reprinting took weeks and much of the value of the publicity and serialization was lost.

There was one question that remained unanswered. Why did I say that the hero was a northerner from Burnley? I truly have no idea. I had seen the destination ‘Burnley’ on parcels I had handled while on a Christmas vacation job at King’s Cross sorting office. I suppose that invention marked one tiny reluctance to depict myself exactly as I was.

Perhaps this spy fellow is not me after all.

Len Deighton, 2009

The Ipcress File

Secret File No. 1

Prologue

They came through on the hot1 line at about half past two in the afternoon. The Minister didn’t quite understand a couple of points in the summary. Perhaps I could see the Minister.

Perhaps.

The Minister’s flat overlooked Trafalgar Square and was furnished like Oliver Messel did it for Oscar Wilde. He sat in the Sheraton, I sat in the Hepplewhite and we peeped at each other through the aspidistra plant.

‘Just tell me the whole story in your own words, old chap. Smoke?’

I was wondering whose words I might otherwise have used as he skimmed the aspidistra with his slim gold cigarette case. I beat him to the draw with a crumpled packet of Gauloises; I didn’t know where to begin.

‘I don’t know where to begin,’ I said. ‘The first document in the dossier …’

The Minister waved me down. ‘Never mind the dossier, my dear chap, just tell me your personal version. Begin with your first meeting with this fellow …’ he looked down to his small morocco-bound notebook, ‘Jay. Tell me about him.’

‘Jay. His code-name is changed to Box Four,’ I said.

‘That’s very confusing,’ said the Minister, and wrote it down in his book.

‘It’s a confusing story,’ I told him. ‘I’m in a very confusing business.’

The Minister said, ‘Quite,’ a couple of times, and I let a quarter inch of ash away towards the blue Kashan rug.

‘I was in Lederer’s about 12.55 on a Tuesday morning the first time I saw Jay,’ I continued.

‘Lederer’s?’ said the Minister. ‘What’s that?’

‘It’s going to be very difficult for me if I have to answer questions as I go along,’ I said. ‘If it’s all the same to you, Minister, I’d prefer you to make a note of the questions, and ask me afterwards.’

‘My dear chap, not another word, I promise.’

And throughout the entire explanation he never again interrupted.

1Permanently open line.

1

[Aquarius (Jan 20–Feb 19) A difficult day. You will face varied problems. Meet friends and make visits. It may help you to be better organized.]

I don’t care what you say, 18,000 pounds (sterling) is a lot of money. The British Government had instructed me to pay it to the man at the corner table who was now using knife and fork to commit ritual murder on a cream pastry.

Jay the Government called this man. He had small piggy eyes, a large moustache and handmade shoes which I knew were size ten. He walked with a slight limp and habitually stroked his eyebrow with his index finger. I knew him as well as I knew anyone, for I had seen film of him in a small, very private cinema in Charlotte Street, every day for a month.

Exactly one month previous I had never heard of Jay. My three weeks’ termination of engagement leave had sped to a close. I had spent it doing little or nothing unless you are prepared to consider sorting through my collection of military history books a job fit for a fully grown male. Not many of my friends were so prepared.

I woke up saying to myself ‘today’s the day’ but I didn’t feel much like getting out of bed just the same. I could hear the rain even before I drew the curtains back. December in London – the soot-covered tree outside was whipping itself into a frenzy. I closed the curtains quickly, danced across the icy-cold lino, scooped up the morning’s post and sat down heavily to wait while the kettle boiled. I struggled into the dark worsted and my only establishment tie – that’s the red and blue silk with the square design – but had to wait forty minutes for a cab. They hate to come south of the Thames you see.

It always had made me feel a little self-conscious saying, ‘War Office’ to cab drivers; at one time I had asked for the pub in Whitehall, or said ‘I’ll tell you when to stop,’ just to avoid having to say it. When I got out the cab had brought me to the Whitehall Place door and I had to walk round the block to the Horseguards Avenue entrance. A Champ vehicle was parked there, a red-necked driver was saying ‘Clout it one’ to an oily corporal in dungarees. The same old army, I thought. The long lavatory-like passages were dark and dirty, and small white cards with precise military writing labelled each green-painted door: GS 3, Major this, Colonel that, Gentlemen, and odd anonymous tea rooms from which bubbly old ladies in spectacles appeared when not practising alchemy within. Room 134 was just like any other; the standard four green filing cabinets, two green metal cupboards, two desks fixed together face to face by the window, a half full one pound bag of Tate and Lyle sugar on the window-sill.

Ross, the man I had come to see, looked up from the writing that had held his undivided attention since three seconds after I had entered the room. Ross said, ‘Well now,’ and coughed nervously. Ross and I had come to an arrangement of some years’ standing – we had decided to hate each other. Being English, this vitriolic relationship manifested itself in oriental politeness.

‘Take a seat. Well now, smoke?’ I had told him ‘No thanks’ for two years at least twice a week. The cheap inlay cigarette box (from Singapore’s change alley market) with the butterflies of wood grain, was wafted across my face.

Ross was a regular officer; that is to say he didn’t drink gin after 7.30 P.M. or hit ladies without first removing his hat. He had a long thin nose, a moustache like flock wallpaper, sparse, carefully combed hair, and the complexion of a Hovis loaf.

The black phone rang. ‘Yes? Oh, it’s you, darling,’ Ross pronouncing each word with exactly the same amount of toneless indifference. ‘To be frank, I was going to.’

For nearly three years I had worked in Military Intelligence. If you listened to certain people you learned that Ross was Military Intelligence. He was a quiet intellect happy to work within the strict departmental limitations imposed upon him. Ross didn’t mind; hitting platform five at Waterloo with rose-bud in the buttonhole and umbrella at the high port was Ross’s beginning to a day of rubber stamp and carbon paper action. At last I was to be freed. Out of the Army, out of Military Intelligence, away from Ross: working as a civilian with civilians in one of the smallest and most important of the Intelligence Units – WOOC(P).

‘Well I’ll phone you if I have to stay Thursday night.’

I heard the voice at the other end say, ‘Are you all right for socks?’

Three typed sheets of carbon copies so bad I couldn’t read them (let alone read them upside down) were kept steady and to hand by the office tea money. Ross finished his call and began to talk to me, and I twitched facial muscles to look like a man paying attention.

He located his black briar pipe after heaping the contents of his rough tweed jacket upon his desk top. He found his tobacco in one of the cupboards. ‘Well now,’ he said. He struck the match I gave him upon his leather elbow patch.

‘So you’ll be with the provisional people.’ He said it with quiet distaste; the Army didn’t like anything provisional, let alone people, and they certainly didn’t like the WOOC(P), and I suppose they didn’t much like me. Ross obviously thought my posting a very fine tentative solution until I could be got out of his life altogether. I won’t tell you all Ross said because most of it was pretty dreary and some of it is still secret and buried somewhere in one of those precisely but innocuously labelled files of his. A lot of the time he was having ignition trouble with his pipe and that meant he was going to start the story all through again.

Most of the people at the War House, especially those on the intelligence fringes as I was, had heard of the WOOC(P) and a man called Dalby. His responsibility was direct to the Cabinet. Envied, criticized and opposed by other intelligence units Dalby was almost as powerful as anyone gets in this business. People posted to him ceased to be in the Army for all practical purposes and they were removed from almost all War Office records. In the few rare cases of men going back to normal duty from WOOC(P) they were enlisted all over afresh and given a new serial number from the batch that is reserved for Civil Servants seconded to military duties. Pay was made by an entirely different scale, and I wondered just how long I would have to make the remnants of this month’s pay last before the new scale began.

After a search for his small metal-rimmed army spectacles, Ross went through the discharge rigmarole with loving attention to detail. We began by destroying the secret compensation contract that Ross and I had signed in this very room almost three years ago and ended by his checking that I had no mess charges unpaid. It had been a pleasure to work with me, Provisional was clever to get me, he was sorry to lose me and Mr Dalby was lucky to have me and would I leave this package in Room 225 on the way out – the messenger seemed to have missed him this morning.

Dalby’s place is in one of those sleazy long streets in the district that would be Soho, if Soho had the strength to cross Oxford Street. There is a new likely-looking office conversion wherein the unwinking blue neon glows even at summer midday, but this isn’t Dalby’s place. Dalby’s department is next door. His is dirtier than average with a genteel profusion of well-worn brass work, telling of the existence of ‘The Ex-Officers’ Employment Bureau. Est 1917’; ‘Acme Films Cutting Rooms’; ‘B. Isaacs. Tailor – Theatricals a Speciality’; ‘Dalby Inquiry Bureau – staffed by ex-Scotland Yard detectives’. A piece of headed note-paper bore the same banner and the biro’d message, ‘Inquiries third floor, please ring.’ Each morning at 9.30 I rang, and avoiding the larger cracks in the lino, began the ascent. Each floor had its own character – ageing paint varying from dark brown to dark green. The third floor was dark white. I passed the scaly old dragon that guarded the entrance to Dalby’s cavern.