Полная версия:

London Match

Cover designer’s note

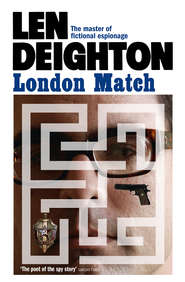

On reading a synopsis for one of Len Deighton’s trilogies I was immediately taken by the sentence, ‘And we are back in the mazes of Secret Service mystery and intrigue – mazes that now lead into Samson’s own tangled past.’ There I found my concept for the London Match cover! I would place him within the maze, trapped, with pathways leading to danger, in the form of the gun, and perhaps worse, the KGB, represented here by one of the agency’s badges – this Soviet-era icon features the hammer and sickle together with Cyrillic letters for ‘KGB’ and ‘USSR’.

Some years ago I was commissioned to design a calendar for a leading British sign company. I decided to use the many door numbers that I had photographed during my travels around the world, showing a different number for each day of the year. I contacted the Prime Minister’s press secretary, who kindly gave me permission to photograph the door of Number 10 Downing Street. This photograph has once again found a good use adorning the back cover of this book of intrigue in London’s Whitehall.

At the heart of every one of the nine books in this triple trilogy is Bernard Samson, so I wanted to come up with a neat way of visually linking them all. When the reader has collected all nine books and displays them together in sequential order, the books’ spines will spell out Samson’s name in the form of a blackmail note made up of airline baggage tags. The tags were drawn from my personal collection, and are colourful testimony to thousands of air miles spent travelling the world.

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

LEN DEIGHTON

London Match

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd 1985

Copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 1985

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2010

Cover designer’s note © Arnold Schwartzman 2010

Cover design and photography © Arnold Schwartzman 2010

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008125004

Ebook Edition © March 2015 ISBN: 9780007387205

Version: 2017-05-23

Contents

Cover

Cover Designer’s Note

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Further Reading

About the Author

By Len Deighton

About the Publisher

Introduction

Despite its title, London Match is a book largely about Berlin. The Berliners were familiar to me; their general demeanour; their humour closely resembled the cocky Londoners I grew up among. But the physical texture of Berlin is not like London, which is generously ventilated with parks and squares. Berlin is martial and monolithic and always has been. Berlin is like no other town I have ever seen. It fascinates me, and in many ways it became my home but there is no denying its grim grey ugliness. Its wide streets make the unrelenting vista of apartment blocks seem less oppressive. But only slightly so. To cope with overcrowding, the great apartment blocks were built one behind the other. Some tenements were so vast that there were three or four Hinterhöfe – or back courtyards. These were so small that sunlight was lost before it could find its way into the hintermost yard. In the early thirties it was calculated that more than ninety per cent of Berlin’s population were packed tightly into these grim five-storey buildings. Berlin, expanded by reparations of the Franco–Prussian War, was designed to absorb the impoverished agricultural workers who came flooding from the Eastern lands seeking jobs in the factories and sweatshops.

Ugly, dirty and crowded – sweaty in summer and freezing in winter – what is the secret attraction of this town? The population is a part of it. The endless upheavals of the past century have brought a weird mixture of people to a town that has never found its place in history. And like many others regularly brought to the brink of despair, Berliners have learned how to smile. Always from the east, there came to the city a steady stream of people looking for shelter. Persecution drove many, and revolution brought more. Painters and writers such as George Grosz and Alfred Döblin provided a lasting record of a town where skirts were short and pounding jazz was at its most frenetic. Emperor Wilhelm had disappeared into exile and Czarist Dukes were working as nightclub doormen. Sex, psychology and cycle racing were major obsessions, and money was singularly meaningful in a town where the currency had collapsed to zero time and time again.

After the debacle in the summer of 1945 the Red Army occupied the Eastern half of the city while fugitives of every kind sought a hazardous sanctuary in its West. But there was no sanctuary; just new kinds of danger. Only the agile survived. Some were saints and some were despicable but most of them were somewhere in between. I came to know many of Berlin’s dodgers and drifters but I had no right to judge them and didn’t attempt to do so. This was not just because I was a writer. Many years ago, I resolved never to resort to the poison of hatred. I had found that hatred wears and destroys the hater and it erects a barrier to understanding that makes objectivity impossible. This had an effect on my writing. Critics remarked upon the absence of villains and the neutrality of the storyteller. I didn’t mind this verdict. Researching my World War Two history books had already brought me into contact with a wide range of veterans of all ranks and specializations, and from both sides of the fighting. By the time I came to write London Match I was being discreetly approached by jaded warriors of the Cold War. These included people at many different levels, with many different motives; some in no way benign. I learned a new sort of discretion. The anecdotal material built up quickly and I soon had enough material for a hundred Bernard Samson books. But books are not assemblies of anecdotes, no matter how dramatically effective, disgusting, inhuman or deeply moving, the stories proved. The nine Bernard Samson stories would stand or fall on the credibility of the principal characters and ever-changing social situation to which they were exposed. Here was a boardroom drama in which the consequence of being ‘outvoted’ was not losing a job, but losing your life. It was an elderly Silesian building contractor who said that to me. He wasn’t talking about my books; he was talking about the dangerous cross-border life he had survived in his youth. He had been ‘out voted’ without losing his life, but some of the fingernails of his left hand were missing.

The times in which our story is set were times of confusion. Western Europe had been saved by the spilled blood of young Americans, and there was widespread gratitude, admiration and respect for the nation which was now the world’s most powerful and most economically successful. But Eastern Europe was ruled by Stalin; a brutal despot who had at one time befriended Hitler and his criminal regime. The Red Army which had invaded Poland and the Baltic states was now used to snuff out any glimmer of democracy in a vast area stretching from Vladivostok to the edge of West Germany. For most people in the West there was a simple distinction between good and evil, between the free societies and the totalitarian ones. But not for everyone. As the nineteen sixties became the seventies there was a slow shift in loyalties. No one openly disputed the existence of Soviet Russia’s secret police, its gulags and the number of its citizens who disappeared each year. But the communist propaganda machine persuaded many Europeans that America’s military presence, and the weapon technology that discouraged Moscow’s territorial ambitions, was as much of a threat as the armies of the USSR. Such people – many of them academics, writers, intellectuals and politicians – liked to proclaim that the USA was just as bad as the USSR. Some said it was worse. Some said that Marxist theory provided a promise of world order that was inevitable and desirable.

The advanced world was split into two distinct halves. The dividing line was drawn down through the middle of Germany. Grimly determined Marxists of the DDR built a barrier against the Federal Republic and killed any of their compatriots trying to join the exuberant capitalists on the other side of it. For added complexity, the town of Berlin had been created as an island in the middle of the DDR and this island was neatly divided between the two combatants. Berlin became the place where the fate of the world would be decided. What writer could resist such a fateful and bloody forum, or should that be amphitheatre? Not I. This was not old history. This was now. This was happening all around me and it was happening to people I knew well.

The fires of the misnamed Cold War did not burn with consistent fury. There were times when both sides toned down their activities for weeks at a time. Sometimes this was a result of orders due to a relaxing of attitudes between Moscow, London and Washington. But more often it was because the people at the sharp end of the conflict wearied, or needed rehabilitation after some particularly destructive blow. I have tried to reflect the way in which this happened. And while the nine books are not in any way an attempt to write Cold War history, I have linked the episodes to actual happenings. And, because writers of fiction are able to test the boundaries of secrecy, I was able to use material generously passed to me by those who were gagged by over-assertive officialdom. I put my thanks on record.

Len Deighton, 2010

1

‘Cheer up, Werner. It will soon be Christmas,’ I said.

I shook the bottle, dividing the last drips of whisky between the two white plastic cups that were balanced on the car radio. I pushed the empty bottle under the seat. The smell of the whisky was strong. I must have spilled some on the heater or on the warm leather that encased the radio. I thought Werner would decline it. He wasn’t a drinker and he’d had far too much already, but Berlin winter nights are cold and Werner swallowed his whisky in one gulp and coughed. Then he crushed the cup in his big muscular hands and sorted through the bent and broken pieces so that he could fit them all into the ashtray. Werner’s wife Zena was obsessionally tidy and this was her car.

‘People are still arriving,’ said Werner as a black Mercedes limousine drew up. Its headlights made dazzling reflections in the glass and paintwork of the parked cars and glinted on the frosty surface of the road. The chauffeur hurried to open the door and eight or nine people got out. The men wore dark cashmere coats over their evening suits, and the women a menagerie of furs. Here in Berlin Wannsee, where furs and cashmere are everyday clothes, they are called the Hautevolee and there are plenty of them.

‘What are you waiting for? Let’s barge right in and arrest him now.’ Werner’s words were just slightly slurred and he grinned to acknowledge his condition. Although I’d known Werner since we were kids at school, I’d seldom seen him drunk, or even tipsy as he was now. Tomorrow he’d have a hangover, tomorrow he’d blame me, and so would his wife, Zena. For that and other reasons, tomorrow, early, would be a good time to leave Berlin.

The house in Wannsee was big; an ugly clutter of enlargements and extensions, balconies, sun deck and penthouse almost hid the original building. It was built on a ridge that provided its rear terrace with a view across the forest to the black waters of the lake. Now the terrace was empty, the garden furniture stacked, and the awnings rolled up tight, but the house was blazing with lights and along the front garden the bare trees had been garlanded with hundreds of tiny white bulbs like electronic blossom.

‘The BfV man knows his job,’ I said. ‘He’ll come and tell us when the contact has been made.’

‘The contact won’t come here. Do you think Moscow doesn’t know we have a defector in London spilling his guts to us? They’ll have warned their network by now.’

‘Not necessarily,’ I said. I denied his contention for the hundredth time and didn’t doubt we’d soon be having the same exchange again. Werner was forty years old, just a few weeks older than I was, but he worried like an old woman and that put me on edge too. ‘Even his failure to come could provide a chance to identify him,’ I said. ‘We have two plainclothes cops checking everyone who arrives tonight, and the office has a copy of the invitation list.’

‘That’s if the contact is a guest,’ said Werner.

‘The staff are checked too.’

‘The contact will be an outsider,’ said Werner. ‘He wouldn’t be dumm enough to give us his contact on a plate.’

‘I know.’

‘Shall we go inside the house again?’ suggested Werner. ‘I get a cramp these days sitting in little cars.’

I opened the door and got out.

Werner closed his car door gently; it’s a habit that comes with years of surveillance work. This exclusive suburb was mostly villas amid woodland and water, and quiet enough for me to hear the sound of heavy trucks pulling into the Border Controlpoint at Drewitz to begin the long haul down the autobahn that went through the Democratic Republic to West Germany. ‘It will snow tonight,’ I predicted.

Werner gave no sign of having heard me. ‘Look at all that wealth,’ he said, waving an arm and almost losing his balance on the ice that had formed in the gutter. As far as we could see along it, the whole street was like a parking lot, or rather like a car showroom, for the cars were almost without exception glossy, new, and expensive. Five-litre V-8 Mercedes with car-phone antennas and turbo Porsches and big Ferraris and three or four Rolls-Royces. The registration plates showed how far people will travel to such a lavish party. Businessmen from Hamburg, bankers from Frankfurt, film people from Munich, and well-paid officials from Bonn. Some cars were perched high on the pavement to make room for others to be double-parked alongside them. We passed a couple of cops who were wandering between the long lines of cars, checking the registration plates and admiring the paintwork. In the driveway – stamping their feet against the cold – were two Parkwächter who would park the cars of guests unfortunate enough to be without a chauffeur. Werner went up the icy slope of the driveway with arms extended to help him balance. He wobbled like an overfed penguin.

Despite all the double-glazed windows, closed tight against the cold of a Berlin night, there came from the house the faint syrupy whirl of Johann Strauss played by a twenty-piece orchestra. It was like drowning in a thick strawberry milk shake.

A servant opened the door for us and another took our coats. One of our people was immediately inside, standing next to the butler. He gave no sign of recognition as we entered the flower-bedecked entrance hall. Werner smoothed his silk evening jacket self-consciously and tugged the ends of his bow tie as he caught a glimpse of himself in the gold-framed mirror that covered the wall. Werner’s suit was a hand-stitched custom-made silk one from Berlin’s most exclusive tailors, but on Werner’s thickset figure all suits looked rented.

Standing at the foot of the elaborate staircase there were two elderly men in stiff high collars and well-tailored evening suits that made no concessions to modern styling. They were smoking large cigars and talking with their heads close together because of the loudness of the orchestra in the ballroom beyond. One of the men stared at us but went on talking as if we weren’t visible to him. We didn’t seem right for such a gathering, but he looked away, no doubt thinking we were two heavies hired to protect the silver.

Until 1945 the house – or Villa, as such local mansions are known – had belonged to a man who began his career as a minor official with the Nazi farmers organization – and it was by chance that his department was given the task of deciding which farmers and agricultural workers were so indispensable to the economy that they would be exempt from service with the military forces. But from that time onwards – like other bureaucrats before and since – he was showered with gifts and opportunities and lived in high style, as his house bore witness.

For some years after the war the house was used as transit accommodation for US Army truck drivers. Only recently had it become a family house once more. The panelling, which so obviously dated back to the original nineteenth-century building, had been carefully repaired and reinstated, but now the oak was painted light grey. A huge painting of a soldier on a horse dominated the wall facing the stairs and on all sides there were carefully arranged displays of fresh flowers. But despite all the careful refurbishing, it was the floor of the entrance hall that attracted the eye. The floor was a complex pattern of black, white and red marble, a plain white central disc of newer marble having replaced a large gold swastika.

Werner pushed open a plain door secreted into the panelling and I followed him along a bleak corridor designed for the inconspicuous movement of servants. At the end of the passage there was a pantry. Clean linen cloths were arranged on a shelf, a dozen empty champagne bottles were inverted to drain in the sink and the waste bin was filled with the remains of sandwiches, discarded parsley, and some broken glass. A white-coated waiter arrived carrying a large silver tray of dirty glasses. He emptied them, put them into the service elevator together with the empty bottles, wiped the tray with a cloth from under the sink, and then departed without even glancing at either of us.

‘There he is, near the bar,’ said Werner, holding open the door so we could look across the crowded dance floor. There was a crush around the tables where two men in chef’s whites dispensed a dozen different sorts of sausages and foaming tankards of strong beer. Emerging from the scrum with food and drink was the man who was to be detained.

‘I hope like hell we’ve got this right,’ I said. The man was not just a run-of-the-mill bureaucrat; he was the private secretary to a senior member of the Bonn parliament.

I said, ‘If he digs his heels in and denies everything, I’m not sure we’ll be able to make it stick.’

I looked at the suspect carefully, trying to guess how he’d take it. He was a small man with crew-cut hair and a neat Vandyke beard. There was something uniquely German about that combination. Even amongst the over-dressed Berlin social set his appearance was flashy. His jacket had wide silk-faced lapels, and silk also edged his jacket, cuffs and trouser seams. The ends of his bow tie were tucked under his collar and he wore a black silk handkerchief in his top pocket.

‘He looks much younger than thirty-two, doesn’t he?’ said Werner.

‘You can’t rely on those computer printouts, especially with listed civil servants or even members of the Bundestag. They were all put onto the computer when it was installed, by copy typists working long hours of overtime to make a bit of spare cash.’

‘What do you think?’ said Werner.

‘I don’t like the look of him,’ I said.

‘He’s guilty,’ said Werner. He had no more information than I did, but he was trying to reassure me.

‘But the uncorroborated word of a defector such as Stinnes won’t cut much ice in an open court, even if London will let Stinnes go into a court. If this fellow’s boss stands by him and they both scream blue murder, he might get away with it.’

‘When do we take him, Bernie?’

‘Maybe his contact will come here,’ I said. It was an excuse for delay.

‘He’d have to be a real beginner, Bernie. Just one look at this place – lit up like a Christmas tree, cops outside, and no room to move – no one with any experience would risk coming into a place like this.’

‘Perhaps they won’t be expecting problems,’ I said optimistically.

‘Moscow know Stinnes is missing and they’ve had plenty of time to alert their networks. And anyone with experience will smell this stakeout when they park outside.’

‘He didn’t smell it,’ I said, nodding to our crew-cut man as he swigged at his beer and engaged a fellow guest in conversation.

‘Moscow can’t send a source like him away to their training school,’ said Werner. ‘But that’s why you can be quite certain that his contact will be Moscow-trained: and that means wary. You might as well arrest him now.’

‘We say nothing; we arrest no one,’ I told him once again. ‘German security are doing this one; he’s simply being detained for questioning. We stand by and see how it goes.’

‘Let me do it, Bernie.’ Werner Volkmann was a Berliner by birth. I’d come to school here as a young child, my German was just as authentic as his, but because I was English, Werner was determined to hang on to the conceit that his German was in some magic way more authentic than mine. I suppose I would feel the same way about any German who spoke perfect London-accented English, so I didn’t argue about it.