скачать книгу бесплатно

Picture me, a scruffy tourist in bush shirt and slacks, trudging along Cairo’s wide and dusty boulevards and through its grimy alleys. It is hot and I am weary, my old shoes are buffed to a glass-like sheen because I find it difficult to turn away the shoe-shine ‘boys’ of all ages who guard every street corner. In my hand there is a map. It is not a modern coloured map with adverts for discos and five star hotels; it is a hand-drawn one showing the city as it was in 1941. It is the work of Victor Pettitt and his wife Margaret, whose dedication and unique experience are helping me bridge the years. I look at Victor’s notes and thrust the map under the noses of appropriately aged passers-by and indicate what I am looking for but it is not easy to find someone who remembers a past that they would rather forget. Sometimes I am lucky, and this book was the result of the kindness and help of many people; friends and strangers. I hope you will enjoy it.

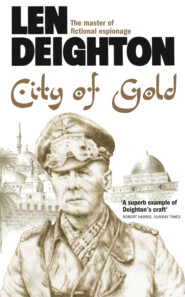

This story of World War Two is set in a short specific period when the city was threatened by the tanks and guns of General Rommel’s Afrika Korps. It was not only the future of Cairo that hung in the balance; a German occupation of the city would have cut Britain off from its vast supporting Imperial complex that stretched from India to Australia. And the greater part of the story I tell is closely based upon historical fact.

Cairo is the world’s oldest city. It has always been the cultural centre of the Arab world and so remains. It sits astride the Eastern Mediterranean and the Suez Canal. It is cosmopolitan in a way that few other cities – and certainly no other Arab city – comes near to being. The unique way in which the River Nile mixed the minerals of the Blue Nile and the rotting vegetation carried by the White Nile made Egypt’s flooded lands exceptionally fertile and fed its population for more than four thousand years.

I find it awesome that in the time of Jesus Christ, visitors came to see the pyramids which had been built two thousand years earlier. Cairo has always known visitors. Cairo controls the only practical route between Europe and the Orient and is the most attractive stopover between Europe and Africa. Travellers are likely to settle permanently in such stopover places, as any New Yorker will confirm. And so Cairo, amid its Muslim millions, is home to a most amazing mixture of races and religions from Copts and Catholics and Jews to Hindus and Buddhists. This diverse array was especially apparent during World War Two.

It was World War Two that made Cairo into a strategic prize, capture of which would have changed history. It is early 1942, when City of Gold begins. Hitler’s armies are occupying the greater part of the continent of Europe from northern Norway to France’s border with Spain. In June 1941 the German army had invaded communist Russia and advanced all the way to the outskirts of Leningrad and Moscow. As the year ended the USA suffered a crippling surprise attack on its Navy in the Pacific; and Germany – fulfilling its agreement with Japan – had declared war upon America.

France had capitulated to the Germans, and French soldiers and sailors in North Africa had also decided to stop fighting. The Italian forces in Libya – an Italian colony – had been waging an unsuccessful battle with the British forces in neighbouring Egypt. To shore up their Italian allies the Germans had sent elements of its armed forces under an obscure but singularly ambitious General named Erwin Rommel, who owed his position to being a favourite of Hitler. As the story opens Rommel’s armoured units were coming uncomfortably close to Cairo.

It is Cairo in that period of early 1942 that I wanted to depict as accurately and dispassionately as I could manage. When I first visited the city, World War Two had been over for ten years. There was plenty of evidence of the earlier times but before starting to plan this book I needed much more. I went back to look afresh. I talked with Egyptian friends and enjoyed the immense benefit of a wife who had lived in Cairo with her parents, who had studied there and speaks and writes Arabic. I scoured diaries and letters, memoirs and endless photo albums. I had become friends with Walther Nehring (who as a Gen-Lt. had commanded the Afrika Korps). Other German desert veterans also provided their viewpoints. But more riches were to be found on my doorstep, for England was packed with people who had spent some wartime years in Egypt. And could they remember!

Looking back, I see that City of Gold had some things in common with my other two books about men and women fighting World War Two. Bomber and Goodbye Mickey Mouse, like City of Gold, were dominated by the environment in which the stories were set. All three books demanded a sympathetic understanding, and persuasive depiction, of foreigners. All three books were subjected to a long period of consideration as I researched time and place. Cairo in 1942, threatened from the desert by German tanks, and in its streets by rioting Egyptians, was undermined by corruption and theft on a massive scale (only to be equalled in scale and audacity during the Vietnam war.) To cover such a complex period, with any chance of reflecting the way it really was, required a large cast of characters: many different people with many different motives tugging in different directions. Only by this means could the bewildering atmosphere of Cairo 1942 be demonstrated. While the other two books also show dissension and dismay they are about unified casts of characters. There is little or no unification of the people in my wartime Cairo. The streets were crowded with Arabs, Italians, Greeks, French and British. There were many different uniforms worn by soldiers, sailors and airmen, South African servicemen and Australians, New Zealanders and Canadians, Indian soldiers and Poles. There were men of the Egyptian army too, although their country remained technically neutral and their declared enemy was the British ‘occupiers’ rather than the Germans at the gates of the city. To add to this social confusion there were countless sub-divisions. Most conspicuous among the civilians were the rich: Egyptian, Greek, French and Italian families, many of whom had lived there for several generations and were determined to keep their elegant lifestyle and privileges. The British enjoyed special social divisions: the most exclusive were civilians permanently employed in the administration, soldiers of Britain’s pre-war regular army were distinguished from men who joined the army simply to fight the war. Combat soldiers from the desert looked with scorn upon the ‘chairborne’ warriors who manned the desks, and of course there always remained the steep class divide between British officers and ‘other ranks’. At the bottom of the heap there was Egypt’s vast population of ragged, half-starved peasantry, of which a sizable proportion was crippled or diseased.

Several of my characters are based upon real people but since no one in the story comes out of it with glory I have not used any real names apart from General Rommel and ‘Ambassador’ Lampson, for whom no one with whom I spoke had a good word. More than one person with firsthand experience thought that many aspects of present-day troubles in the ‘Muddle East’ were largely a legacy of the well-publicised bullying of King Farouk. Some of the episodes here, such as Lampson’s visit to the Palace, are based upon eye-witness descriptions. Most of the places are depicted as accurately as I am able.

Len Deighton, 2011

Prologue

In the final months of 1941, General Erwin Rommel – commander of the Axis armies in North Africa – began to receive secret messages about the British armies that faced him. The source of this secret intelligence was not identified to Rommel. In fact, the contents of the messages sent to him were carefully rewritten to prevent anyone guessing the source of these secrets and how they were obtained. But the messages were startling in their completeness; the dates of arrival of supply ships and their cargoes, the disposition of the Allied armies and air forces, the state of their morale and their equipment, and even what their next operations might be were provided promptly and regularly to Rommel’s intelligence officer.

Said one specialist historian, ‘And what messages they were! They provided Rommel with undoubtedly the broadest and clearest picture of enemy forces and intentions available to any Axis commander throughout the whole war … In the see-saw North African warfare, Rommel had been driven back across the desert by the British … but beginning on January 21, 1942, he rebounded with such vigour that in seventeen days he had thrown the British back 300 miles.’

1

Cairo: January 1942

‘I like escorting prisoners,’ said Captain Albert Cutler, settling back and stretching out his legs along the empty seats. He was wearing a cream-coloured linen suit that had become rumpled during the journey. ‘When I face a long train journey, I try and arrange to do it.’

He was a florid-faced man with a pronounced Glasgow accent. There was no mistaking where he came from. It was obvious right from the moment he first opened his mouth.

The other man was Jimmy Ross. He was in khaki, with corporal’s stripes on his sleeves. He was that rarest of Scots, a Highlander: from a village in Wester Ross. But they’d tacitly agreed to bury their regional differences for this brief period of their acquaintanceship. It was Ross’s pocket chess set that had cemented their relationship. They were both at about the same level of skill. During the journey they must have played fifty games. At least fifty. And that was not counting the little demonstrations that Cutler had pedantically given him: openings and endings from some of the great games of the chess masters. He could remember them. He had a wonderful memory. He said that was what made him such a good detective.

It was an old train, with all the elaborate bobbins and fretwork that the Edwardians loved. The luggage rack was of polished brass with tassels at each end. There was even a small bevelled mirror in a mahogany frame. In the roof there was a fan that didn’t work very well. According to the wind and the direction of the train, the ventilator emitted gusts of sooty smoke from the locomotive. It did it now, and Ross coughed.

There came the sounds of passengers picking their way along the corridor. They stumbled past with their kit and baggage and rifles and equipment. They spoke in the tired voices of men who have not slept; the train was very crowded. They couldn’t see in. All the blinds were kept lowered on this compartment, but there was enough sunlight getting through the linen. It made a curious shadowless light.

‘Why would you like that?’ said Jimmy Ross. ‘Escorting prisoners. Why would you like that?’ He had a soft Scots accent that you’d only notice if you were looking for it. Jimmy Ross was slim and dark and more athletic than Cutler, but both men were much the same. Their similarities of upbringing – bright, working-class, grammar school graduates without money enough to go up to university – had more than once made them exchange looks that said, There but for the grace of God go I, or words to that effect.

‘I wear my nice civvy clothes, and I get a compartment to myself. Room to put my feet up. Room to stretch out and sleep. No one’s bothered us, have they? I like it like that, especially on these trains.’ Cutler tugged at the window blind and raised it a few inches to look out at the scenery. On the glass, as on the windows to the corridor, there were large gummed-paper notices that bore the royal coat of arms, the smudged rubber stamps, the scrawled signatures of a representative of the provost marshal, and the words RESERVED COMPARTMENT in big black letters. No one with any sense would have intruded upon them.

Bright sunlight came into the compartment as he raised the blind. So did the smell of excrement, which was spread on the fields as fertiliser. Cutler blinked. Outside, the countryside was green: dusty, of course, like everything in this part of the world, but very green. This was Egypt in winter: the fertile region.

The train clattered and groaned. It was not going fast; Egyptian trains never went fast. Scrawny dark-skinned men, riding donkeys alongside the track, stared back at them. In the fields, women were bending to weed a row of crops. They stepped forward, still in line, like soldiers. ‘A long time yet,’ pronounced Cutler, looking at his watch. He lowered the blind again. When the train reached Cairo the two men would part. Cutler, the army policeman, would take up his nice new appointment with Special Investigation Branch Headquarters, Middle East. Jimmy Ross would be thrown into a stinking army ‘glasshouse’. He knew he could expect a very rough time while awaiting court-martial. The military prison in Cairo had a bad reputation. After he’d been tried and found guilty, he might be sent to one of the army prisons in the desert. Ross smiled sadly, and Cutler felt sorry for him. It hadn’t been a bad journey; two Scotsmen can always find something in common.

‘Have you never been attacked?’ said Ross.

‘Attacked?’

‘By prisoners. Don’t men get desperate when they are under arrest?’

Cutler chuckled. ‘You wouldn’t hurt me, would you?’ There was not much difference in their ages or their builds. Cutler wasn’t frightened of the prisoner. Potbellied as he was, he felt physically superior to him. In Glasgow, as a young copper on the beat, he’d learned how to look after himself in any sort of rough-house.

‘I’m not a violent man,’ said Ross.

‘You’re not?’ Cutler laughed. Ross was charged with murder.

Reading his thoughts, Jimmy Ross said, ‘He had it coming to him. He was a rotten bastard.’

‘I know, laddie.’ He could see that Jimmy Ross was a decent enough fellow. He’d read Ross’s statement, and those of the witnesses. Ross was the only NCO there. The officer was an idiot who would have got them all killed. And he pulled a gun on his men. That was never a good idea. But Cutler was tempted to add that his victim’s being a bastard would count for nothing. Ross was an ‘other rank’, and he’d killed an officer. That’s what would count. In wartime on active service they would throw the book at him. He’d be lucky to get away with twenty years’ hard labour. Very lucky. He might get a death sentence.

Jimmy Ross read his thoughts. He was sitting handcuffed, looking down at the khaki uniform he was wearing. He fingered the rough material. When he looked up he could see the other man was grimacing. ‘Are you all right, captain?’

Cutler did not feel all right. ‘Did you have that cold chicken, laddie?’ Cutler had grown into the habit of calling people laddie. As a police detective-inspector in Glasgow it was his favoured form of address. He never addressed prisoners by their first names; it heightened expectations. Other Glasgow coppers used to say sir to the public but Cutler was not that deferential.

‘You know what I had,’ said Ross. ‘I had a cheese sandwich.’

‘Something’s giving me a pain in the guts,’ said Cutler.

‘It was the bottle of whisky that did it.’

Cutler grinned ruefully. He’d not had a drink for nearly a week. That was the bad part of escorting a prisoner. ‘Get my bag down from the rack, laddie.’ Cutler rubbed his chest. ‘I’ll take a couple of my tablets. I don’t want to arrive at a new job and report sick the first minute I get there.’ He stretched out on the seat, extending his legs as far as they would go. His face had suddenly changed to an awful shade of grey. Even his lips were pale. His forehead was wet with perspiration, and he looked as if he might vomit.

‘It’s a good job, is it?’ Jimmy Ross pretended he could see nothing wrong. He got to his feet and, with his hands still cuffed, got the leather case. He watched Cutler as he opened it.

Cutler’s hands were trembling so that he had trouble fitting the key into the locks. With the lid open Ross reached across, got the bottle and shook tablets out of it. Cutler opened his palm to catch two of them. He threw them into his mouth and swallowed them without water. He seemed to have trouble getting the second one down. His face hardened as if he was going to choke on it. He frowned and swallowed hard. Then he rubbed his chest and gave a brief bleak smile, trying to show he was all right. He’d said he often got indigestion; it was the worry of the job. Ross stood there for a moment looking at him. It would be easy to crack him over the head with his hands. He could bring the steel cuffs down together onto his head. He’d seen someone do it on stage in a play.

For a moment or two Cutler seemed better. He tried to overcome his pain. ‘I’ve got to find a spy in Cairo. I won’t be able to find him, of course, but I’ll go through the motions.’ He closed the leather case. ‘You can leave it there. I will be changing my trousers before we arrive. That’s the trouble with linen; it gets horribly wrinkled. And I want to look my best. First impressions count.’

Ross sat down and watched him with that curiosity and concerned detachment with which the healthy always observe the sick. ‘Why won’t you be able to find him?’ Being under arrest had not lessened his determined hope that Britain would win the war, and this fellow Cutler should be trying harder. ‘You said you were a detective.’

‘Ah! In Glasgow before the war, I was. CID. A bloody good one. That’s why the army gave me the rank straight from the force. I never did an officer’s training course. They were short of trained investigators. They sent me to Corps of Military Police Depot at Mytchett. Two weeks to learn to march, salute, and be lectured on military law and court-martial routines. That’s all I got. I came straight out here.’

‘I see.’

Cutler became defensive. ‘What chance do I stand? What chance would anyone stand? They can’t find him with radio detectors. They don’t think he’s one of the refugees. They’ve exhausted all the usual lines of investigation.’ Cutler was speaking frankly in a way he hadn’t spoken to anyone for a long time. You could speak like that to a man you’d never see again. ‘It’s a strange town, full of Arabs. This place they’re sending me to: Bab-el-Hadid barracks – there’s no one there … I mean there are no names I recognise, and I know the names of all the good coppers. They are all soldiers.’ He said it disgustedly; he didn’t think much of the army. ‘Conscripts … a couple of lawyers. There are no real policemen there at all; that’s my impression anyway. And I don’t even speak the language. Arabic; just a lot of gibberish. How can I take a statement or do anything?’ Very slowly and carefully Cutler swung his legs round so he could put his feet back on the floor again. He leaned forward and sighed. He seemed to feel a bit better. But Ross could see that having bared his heart to a stranger, Cutler now regretted it.

‘So why did they send for you?’ said Ross.

‘You know what the army’s like. I’m a detective; that’s all they know. For the top brass, detectives are like gunners or bakers or sheet-metal workers. One is much like the other. They don’t understand that investigation is an art.’

‘Yes. In the army, you are just a number,’ said Ross.

‘They think finding spies is like finding thieves or finding lost wallets. It’s no good trying to tell them different. These army people think they know it all.’ A sudden thought struck him. ‘Not a regular, are you?’

‘No.’

‘No, of course not. What did you do before the war?’

‘I was in the theatre.’

‘Actor?’

‘I wanted to be an actor. But I settled for stage managing. Before that I was a clerk in a solicitor’s office.’

‘An actor. Everyone’s an actor, I can tell you that from personal experience,’ said Cutler. He suddenly grimaced again and rubbed his arms, as if at a sudden pain. ‘But they don’t know that … Jesus! Jesus!’ and then, more quietly, ‘That chicken must have been off…’ His voice had become very hoarse. ‘Listen, laddie… Oh, my God!’ He’d hunched his shoulders very small and pulled up his feet from the floor, like an old woman frightened of a mouse. Then he hugged himself; with his mouth half open, he dribbled saliva and let out a series of little moaning sounds.

Jimmy Ross sat there watching him. Was it a heart attack? He didn’t know what to do. There was no one to whom he could go for assistance; they had kept apart from the other passengers. ‘Shall I pull the emergency cord?’ Cutler didn’t seem to hear him. Ross looked up, but there was no emergency cord.

Cutler’s eyes had opened very wide. ‘I think I need…’ He was hugging himself very tightly and swaying from side to side. All the spirit had gone out of him. There was none of the prisoner-and-guard relationship now; he was a supplicant. It was pitiful to see him so crushed. ‘Don’t run away.’

‘I won’t run away.’

‘I need a doctor…’

Ross stood up to lean over him.

‘Awwww!’

Hands still cuffed together, Ross reached out to him. By that time it was too late. The policeman toppled slightly, his forehead banged against the woodwork with a sharp crack, and then his head settled back against the window. His eyes were staring, and his face was coloured green by the light coming through the linen blind.

Ross held him by the sleeve and stopped him from falling over completely. Hands still cuffed, he touched Cutler’s forehead. It was cold and clammy, the way they always described it in detective stories. Cutler’s eyes remained wide open. The dead man looked very old and small.

Suddenly Ross stopped feeling sorry. He felt a pang of fear. They would say he’d done it, he’d murdered this military policeman: Captain Cutler. They’d say he’d fed him poison or hit him the way he’d hit that cowardly bastard he’d killed. He tried to still his fears, telling himself that they couldn’t hang you twice. Telling himself that he’d look forward to seeing their faces when they found him with a corpse. It was no good; he was scared.

He stared down at the handcuffs. His wrists had become chafed. He might as well unlock them. That was the first thing to do, and then perhaps he’d get help. Cutler kept the key in his right-side jacket pocket, and it was easy to find. There were other keys on the same ring, including the little keys to Cutler’s other luggage that was in the baggage car. He rubbed his wrists. It was good to get the cuffs off. Cutler had been decent enough about the handcuffing. One couldn’t blame a man for taking precautions with a murderer.

With the handcuffs removed, Jimmy Ross felt different. He juggled the keys in the palm of his hand and on an impulse unlocked Cutler’s leather case and opened it. There were papers there: official papers. Ross wanted to see what the authorities had written about his case.

It was amazing what people carried around with them: a bottle of shampoo, a silver locket with the photo of an older woman, a silver-backed hairbrush, and a letter from a Glasgow branch of the Royal Bank of Scotland acknowledging that he’d closed his mother’s account with them. It was dated three months before. Now that the mail from Britain went round Africa, it was old by the time it arrived. A green cardboard file of papers about Cutler’s job in Cairo. ‘Albert George Cutler … To become a major with effect the first December 1941.’ So the new job brought him promotion too. Acting and unpaid, of course; promotions were usually like that, as he knew from working in the orderly room. But a major; a major was a somebody.

He looked at the other papers in the case but he could find nothing about himself. Travel warrant, movement order, a brown envelope containing six big white five-pound notes and seven one-pound notes. A tiny handyman’s diary with tooled leather cover and a neat little pencil in a holder in its spine. Then he found the amazing identity pass that all the special investigation staff carried, a pink-coloured SIB warrant card. He’d heard rumours about these passes but he didn’t think he’d ever hold one in his hands. It was a carte blanche. The rights accorded the bearer of the pass were all-embracing. Captain Cutler could wear any uniform or civilian clothes he chose, assume any rank, go anywhere and do anything he wished.

A pass like this would be worth a thousand pounds on the black market. He looked at the photograph of Cutler. It was a poor photograph, hurriedly snapped by some conscripted photographer and insufficiently fixed so that the print was already turning yellow. It was undoubtedly Cutler, but it could have been any one of a thousand other men.

It was then that the thought came to him that he could pass himself off as Cutler. Cutler’s hair was described as straight, and Ross’s hair was wavy, but with short army haircuts there was little difference to be seen. When alive Cutler had been red complexioned, while Ross was tanned and more healthy looking. But the black-and-white photograph revealed nothing of this. Their heights were different, Cutler shorter by a couple of inches, but it seemed unlikely that anyone would approach him with a tape measure and check it out. He stood up and looked in the little mirror, and held in view the photo to compare it. It was not a really close likeness, but how many people asked a military police major to prove his identity? Not many.

Then his heart sank as he realised that the clothes would give them away. He’d have to arrive wearing the white linen suit.

Changing clothes would be too much; he couldn’t go through with that. He opened Cutler’s other bag. It was a fine green canvas bag of the sort that equipped safaris. Inside, right at the top, was the pair of white canvas trousers. Ross made sure that the blinds were down and then he changed into the trousers. Damn! They were a couple of inches too short.

Then he had another idea. He’d get off the train in his corporal’s uniform and use the SIB pass. But that would leave the corpse wearing mufti. Would they believe that an army corporal would arrive in civilian clothes? Why not? They’d arrested Ross in the corporal’s uniform he was wearing. Had he been wearing a civilian suit, they would not have equipped him with a uniform for the journey, would they?

He looked at himself again. Certainly those white trousers would not do. With an overcoat he might have been able to let the waist of the trousers go low enough to look normal. But without an overcoat he’d look like a circus clown. Shit! He could have sobbed with frustration.

Well, it was the corporal’s uniform or nothing. He looked at himself in the little mirror and tried imitating Cutler’s Glasgow accent. It wasn’t difficult. To his reflection he said, ‘This is the chance you’ve always prayed for, Jimmy. The star has collapsed and you’re going on in his place. Just make sure you get your bloody lines right.’

It was worth a try. But he wouldn’t need the voice. All he wanted to do was just get off the train, and disappear into the crowds. He’d find some place to hide for a few days. Then he’d figure out where to go. In a big town like Cairo he’d have a chance to get clear away. Rumour said the town was alive with military criminals and deserters and black-market crooks. What about money? If he could find some little army unit in the back of beyond, he’d bowl in and ask for a ‘casual pay parade’. He knew how that was done; transient personnel were always wanting pay. Meanwhile, he had nearly forty pounds. In a place like Cairo that would be enough for a week or two: maybe a month. He’d have to find a hotel. Such places as the YMCA and the hostels and other institutions were regularly checked for deserters. The real trouble would be the railway station and getting past the military police patrols. Those red-capped bastards hung around stations like wasps around a jam jar. He had Cutler’s pass, but would they believe he was an SIB officer? More likely they’d believe that he was a corporal without a leave pass.

He sat down and tried to think objectively. When he looked up he was startled to find the dead eyes of Cutler staring straight at him. He reached out and gently touched his face, half expecting the dead man to smile or speak. But Cutler was dead, very dead. Damn him! Jimmy Ross got up and went to another seat. He had to think.

About five minutes later he started. He had to be very methodical. First he would empty his own pockets, and then he would empty Cutler’s pockets. They had to completely change identity. Don’t forget the signet ring his mother had given him; it would be a shame to lose it but it might be convincing. He’d have to strip the body. He must look inside shirts and socks for name tapes and laundry labels too. Officers didn’t do their own washing: they were likely to have their names on every last thing. There was an Agatha Christie yarn in which the laundry label was the most incriminating clue. One slip could bring disaster.

As the train clattered over the points to come into Cairo station, Ross undid the heavy leather strap that lowered the window. Everyone else on the train seemed to have the same idea. There were heads bobbing from every compartment. The smell of the engine smoke was strong but not so powerful as to conceal the smell of the city itself. Other cities smelled of beer or garlic or stale tobacco. Cairo’s characteristic smell was none of those. Here was a more intriguing mix: jasmine flowers, spices, sewerage, burning charcoal, and desert dust. Ross leaned forward to see better.

He need not have bothered. They would have found the compartment; they were looking for the distinctive RESERVED signs. There were two military policemen complete with red-topped caps and beautifully blancoed webbing belts and revolver holsters. With them there was a captain wearing his best uniform: starched shirt, knitted tie and a smart peaked cap. A military police officer! The only other time he’d ever seen one of those was when he was formally arrested.

It was the officer who noticed Ross leaning out of the window of the train and called to him. ‘Major Cutler! Major Cutler!’

The train came to a complete halt with a great burst of steam and the shriek of applied brakes. The sounds echoed within the great hall.

‘Major Cutler?’ The officer didn’t know whether to salute this man in corporal’s uniform.

‘Yes. I’m Cutler. An investigation. I haven’t had a chance to change,’ said Ross, as casually as he could. He was nervous; could they hear that in his voice? ‘I’m stuck with this uniform for the time being.’ He wondered whether he should bring out his identity papers but decided that doing so might look odd. He hadn’t reckoned on anyone’s coming to meet him. It had given him a jolt.

‘Good journey, sir? I’m Captain Marker, your number one.’ Marker smiled. He’d heard that some of these civvy detectives liked to demonstrate their eccentricities. He supposed that wearing ‘other ranks’ uniforms was one of them. He realised that his new master might take some getting used to.

Jimmy Ross stayed at the window without opening the train door. ‘We’ve got a problem, Marker. I’ve got a prisoner here. He’s been taken sick.’

‘We’ll take care of that, sir.’

‘Very sick,’ said Ross hastily. ‘You are going to need a stretcher. He was taken ill during the journey.’ With Marker still looking up at him quizzically, Ross improvised. ‘His heart, I think. He told me he’d had heart trouble, but I didn’t realise how bad he was.’

Marker stepped up on the running board of the train and bent his head to see the figure hunched in his corner seat. Civilian clothes: a white linen suit. Why did these deserters always want to get into civilian clothes? Khaki was the best protective colouring. Then Marker looked at his new boss. For a moment he was wondering if he’d beaten the prisoner. There was no blood or marks anywhere to be seen but men who beat prisoners make sure there is no such evidence.

Ross saw what he was thinking. ‘Nothing like that, Captain Marker. I don’t hit handcuffed men. Anyway he’s been a perfect prisoner. But I don’t want the army blamed for ill-treating him. I think we should do it all according to the rule book. Get him on a stretcher and get him to hospital for examination.’

‘There’s no need for you to be concerned with that, sir.’ Marker turned to one of his MPs. ‘One of you stay with the prisoner. The other, go and phone the hospital.’

‘He’s still handcuffed,’ said Ross who’d put the steel cuffs on the dead man’s wrists to reinforce his identity as the prisoner. ‘You’ll need the key.’

‘Just leave it to my coppers,’ said Marker taking it from him and passing it to the remaining red cap. ‘We’d better hurry along and sort out your baggage. The thieves in this town can whisk a ten-ton truck into thin air and then come back for the logbook.’ Marker looked at him; Ross smiled.

Ten billion particles of dust in the air picked up the light of the dying sun that afternoon, so that the slanting beams gleamed like bars of gold. So did the smoke and steam and the back-lit figures hurrying in all directions. Even Marker was struck by the scene.

‘They call it the city of gold,’ he said. There was another train departing. It shrieked and whistled in the background while crowds of soldiers and officers were fussing around the mountains of kitbags and boxes and steamer trunks that were piling up high on the platforms.

‘Yes, I used to know a poem about it,’ said Ross. ‘A wonderful poem.’

‘A poem?’ Marker was surprised to hear that this man was a devotee of poetry. In fact he was astonished to learn that any SIB major, particularly one who’d risen to this position through the ranks of the Glasgow force, would like any poem. ‘Which one was that, sir?’

Ross was suddenly embarrassed. ‘Oh, I don’t remember exactly. Something about Cairo’s buildings and mud huts looking like the beaten gold the thieves plunder from the ancient tombs.’ He’d been about to recite the poem, but suddenly the life was knocked out of him as he remembered that his own kitbag was there too. His first impulse was to ignore it, but then it would go to ‘Lost Luggage’ and they’d track it back to a prisoner named James Ross. What should he do?

‘I should have brought three men,’ said Marker apologetically as they stood near the baggage car, looking at the luggage. ‘I wasn’t calculating on us having to sort out your own gear.’

‘Just one more bag,’ said Ross. ‘Green canvas, with a leather strap round it. There it is.’ Then he saw the kitbag. Luckily it had suffered wear and tear over the months since his enlistment. The stencilled name ROSS and his regimental number had faded. ‘And the brown kitbag.’