Полная версия:

The Compass Rose

GAIL DAYTON

The Compass Rose

For Robert. Thanks for all the brainstorming help

and for paying attention when I told you

how much fun fantasy was. I’m glad you’re my kid.

And for Lindi. Keep at it. Dreams do come true.

CONTENTS

CAST OF CHARACTERS

GLOSSARY

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CAST OF CHARACTERS

Kallista Varyl-captain in the Adaran army, naitan of the North, lightning thrower

Torchay Omvir-Adaran sergeant, Kallista’s bodyguard

Stone, Warrior vo’Tsekrish-Tibran warrior

Fox, Warrior vo’Tsekrish-Tibran warrior, fighting partner to Stone

Aisse vo’Haav-Tibran woman

Obed im-Shakiri-Southron trader

Joh Suteny-Adaran guard lieutenant

Serysta Reinine-ruler of Adara, North naitan truthsayer

Viyelle Torvyll-Adaran prinsipella of Shaluine

Belandra of Arikon-the near legendary godstruck naitan who unified the first four prinsipalities to establish Adara, a thousand (or so) years ago

Huryl Kovallyk-Serysta’s high steward

Erunde Nonnald-Steward’s 4th undersecretary

Irysta Varyl-Kallista’s birth mother, East naitan healer

Karyl & Kami Varyl-Kallista’s twin sisters by blood

Mother Edyne-Mother Temple prelate in Ukiny

Huyis Uskenda-Adaran general in Ukiny

Merinda Kyndir-Adaran East naitan healer

Mother Dardra-Kallista’s 5th mother, Riverside temple prelate and administrator in Turysh

Domnia Varyl-founder of the Varyl bloodline, West naitan and prelate

Oughrath, Bureaucrat vo’Haav-docks and trading official in Haav

Beltis-South naitan firethrower, Adaran trooper under Kallista’s command

Hamonn-Beltis’s bodyguard

Adessay-North naitan earthmover, trooper under Kallista’s command

Kadrey-Adessay’s bodyguard

Iranda-South naitan lightmaker, trooper under Kallista’s command

Rynver-East naitan plantgrower, trooper under Kallista’s command

Mora-South naitan foodspoiler, trooper under Kallista’s command

Borril-Adaran guard sergeant

Smynthe-Tibran female magic hunter

Gweric-Tibran male magic hunter

GLOSSARY

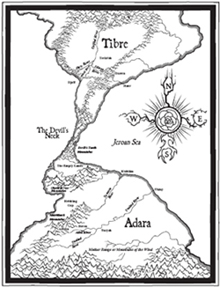

Adara-the nation occupying the northern half of the continent south of the Jeroan Sea

aila (aili)-Sir or Madam, a title of respect in Adara

Alira River-tributary of the Taolind, descending from the Shieldback Mountains near Arikon

Arikon-capital of Adara at the edge of the Shieldback Mountains in western Adara

Athril River-center, navigable branch of the two western arms of the Unified River

Boren-town where the Alira becomes unnavigable, where the road to Arikon begins

Devil’s Neck-impassable isthmus connecting Tibran continent to the Adaran

Devil’s Tooth Mountains-the mountains that make the Devil’s Neck impassable, habitable only in the lower southern reaches, above the Empty Lands

Djoff-Tibran port on the western coast, at the mouth of the Athril

Dzawa-Tibran city where the Silixus descends from the central plateau to the coastal plain

Empty Lands-an ancient lava-flow desert on the northern edge of Adara, thought to have been created in the Demon Wars 2000 years ago, habitable if one is careful

Filorne-prinsipality north of Taolind, upriver from Turysh; coat of arms: crossed swords, black and silver

Gadrene-Ukiny’s prinsipality; coat of arms: blue-and-white ship

Haav-main port of Tibre, at the mouth of the Silixus River, easternmost of the rivers coming out of Tsekrish

Heldring Gap-wide valley in west central Adara, famed for the mines on either flank, and the swords made there

ilian (iliani)-four to twelve Adaran adults joined into a family unit, their version of marriage

ilias (iliasti)-spouse (spouses)

Kishkim-port city west of Ukiny, at the mouth of the Tunnassa River, known for its swamps and smugglers

Korbin-northernmost Adaran prinsipality, just south of Devil’s Neck land bridge in the Devil’s Tooth Mountains and the Empty Lands, Torchay’s home prinsipality; coat of arms: red-and-gold stag

Mountains of the Wind, Mother Range-mountain range that marks Adara’s southern border, Mother Range is Southron name; Mountains of the Wind is name used by Adarans

naitan (naitani)-a person with a magical gift

Obre River-westernmost branch of the Unified River, fast and full of rapids

Okreti di Vos Mountains-the name means “Arms of God” in the ancient language; separated from the Devil’s Tooth range by a lava-flow desert and from the Shieldbacks by the Heldring Gap

prinsep (prinsipi)-the ruler (male or female) of one of the once-independent governmental units now joined together to create Adara

prinsipality-the province ruled by a prinsep

prinsipella-the offspring (male or female) of a prinsep

Reinine-the priestess-queen chosen by the collective Adaran prelates and prinsipi to rule Adara; a lifetime appointment, but not hereditary

Shaluine-prinsipality north of Turysh, between Taolind and Tunassa Rivers; coat of arms: gold lion

Shieldback Mountains-a western mountain range separated from the Mother Range by the Taolind and Alira River valleys and from the Okreti di Vos Mountains by the Heldring Gap, where Arikon is located

Silixus River-important transport river in Tibre, easternmost of the three branches of the Unified River, the only one that empties into the Jeroan Sea

Taolind River-Adara’s major river, leading from northern coast at Ukiny southwest deep into the interior

Tibre-the nation made up of most of the continent north of the Jeroan Sea

Tsekrish-capital of Tibre, on the high central plateau where the Unified River breaks into three

Tunassa River-secondary river, north of the Taolind, rarely navigable, empties into Jeroan Sea at Kishkim, runs southwest to northeast

Turysh-Kallista’s hometown, at the confluence of the Taolind and Alira Rivers, also the name of a prinsipality, coat of arms: green tree surmounted by a gold crown

Ukiny-port city on Adara’s northern coast, at the mouth of the Taolind River

Unified River-flows into Tsekrish from northern mountains, once considered sacred

CHAPTER ONE

The wind off the sea snapped the banners to attention on the city walls. It ripped at the edges of the captain’s tight queue and set the two white ribbons of her rank fluttering from her shoulders. Kallista Varyl tugged her tunic, blue for the direction of her magic, into better order. Yet one more time she wished that if she had to have North magic, she might have been given some more useful type. Directing winds, for instance.

She abhorred the way the wind here in Ukiny constantly tugged at her hair, destroying any attempt at neatness and order. And wind magic had civilian uses. Practical, productive uses. Her magic had no use other than war, so here she stood, captain of the Reinine’s Own, on the walls of this besieged city waiting for the coming attack.

“What’s the mood below?” Kallista continued her slow patrol of the ramparts.

“Quiet. Tense. They know what’s coming.” Her shadow moved forward to fall into step beside her. Torchay Omvir had been her constant companion for the past nine years. His tunic was bodyguard’s black trimmed with blue to show whom he served. The folded ribbon set on his sleeve below the shoulder indicated his rank. When they went into summer uniform in a few more weeks, his tattooed rank would show on his upper arm. Most of the men making the military a career did the same.

“Not too tense I hope.”

He shrugged. “Who can say until the moment comes and the battle begins?” Torchay paced alongside her, always keeping his lean height interposed between Kallista and the enemy spread out on the fields and beaches below.

Their white tents dotted the land like virulent pustules of infection as far as the unaided eye could see. Ukiny stood on the lone patch of rock floating to the surface of Adara’s flat northern coast. The city’s chalk-white limestone walls towered over the plains where the enemy camped. That advantage hadn’t meant much so far.

“True.” She neither needed nor even wanted the information she’d asked for. She asked to force Torchay to answer, to have some contact with another human at this loneliest of moments.

Torchay preferred his invisibility, claiming he could protect her better if he went unnoticed. But hair the color of Torchay’s—deep, vibrant red—seldom escaped notice even when ruthlessly confined in a proper military queue. And wherever a military naitan went, everyone knew her bodyguard went also. At moments like this one, Kallista preferred company to protocol.

“Tomorrow?” Torchay stopped beside her at the northwest corner tower.

Kallista stared down at the rubble spilling from the breach in Ukiny’s western wall and on down the steep slope of the carefully constructed glacis below. The setting sun gilded those broken stones, mocking the coming death they heralded.

“Likely,” she said. “At dawn or just before. That’s when I’d attack, when we’re at our most tired.”

The enemy ships had appeared unexpectedly off Ukiny just a week ago, hundreds of them. Adaran ships were built for speed and trade, not fighting. With a North magic naitan to call winds on almost every ship, they rarely had to deal with pirates or more political forms of banditry because their vessels were hard to catch. The few local ships in port when the strangers sailed up had fled. The city—still reeling with astonishment that any would dare invade Adara—had fastened itself inside stout walls.

Soldiers had poured from the clumsy ships, hundreds and hundreds of them, unloading bizarre equipment and strange-looking devices. The foreign army outnumbered the small force garrisoning Ukiny before half their ships had unloaded.

By careful listening at staff meetings, Kallista had gathered that one of the quarrelsome kings on the continent across the Jeroan Sea to the north had taken all the lands he could on his own continent and now had cast his eye toward Adara. No one seemed to know what drove Tibre on its conquest, whether greed, religion or something else. They were strange people according to the traders stranded in town when the ships fled, divided among themselves according to rank, each rank worshipping different gods.

Stranger yet, they had no naitani of their own and were known to kill those from other lands who demonstrated a visible gift of magic. That was why, despite the overwhelming numbers ranged against them, the small Adaran garrison had been confident of victory over the invading Tibrans. If they had no naitani at all, they certainly wouldn’t have any attached to their army.

They had something else. Cannon.

Traders had been bringing reports for a number of years about the wars among the northern kingdoms. They told of a weapon that required no magic to break down walls and fortifications, a weapon far more effective, far more devastating than ballistae or catapults. The Adaran general staff had discounted these tales as exaggerations. The Tibrans might have something, but nothing without magic involved could have such a deadly effect. The generals were wrong.

Now they were paying the price for their smug assumptions. Adara was a nation of merchants, a matriarchal society that used its army primarily to control the aggression of her young men. A long succession of prelate-queens had seen little need for violent expansion. The last of the independent prinsipalities between the impassable Devil’s Neck land bridge to the north and the nearly impassable Mother Range spanning the continent to the south had joined Adara two hundred years ago, the result of diplomacy and trade, not war.

The Reinines in the years since had believed Adara’s superiority so obvious that no other nation would dare challenge it. And they hadn’t, even though some Adaran traders skinned those they traded with a bit too close to the bone. Adara had more naitani than any other land, and the naitani were Adara’s strength.

But they should have expected the other nations to develop alternatives to the magic Adara used so extravagantly. When the traders came home complaining of cloth made waterproof through the use of powders and mechanical techniques, someone should have noticed. This new stuff wasn’t as good as Adaran waterproofing, but it was much cheaper. How far from there to mechanical weapons as effective at massive destruction as a soldier naitan? More effective, because the cannon could be used by anyone and could be forged by the hundreds. A naitan had to be born.

These terrible cannon belched forth fire and destruction. They battered the city walls hour after endless hour, day upon day. The constant boom!-whistle-crack! as the iron ball exploded from the mouth of the weapon, sailed through the air and smashed into stone, was enough to drive anyone into screaming fits. Anyone, that is, of lesser moral fiber than a captain of the Reinine’s Own Naitani.

Kallista had destroyed one of the awful machines, the only naitan of her troop able to do so. The enemy moved them farther from the walls then, and still kept up the relentless bombardment. These cannon could fire their iron balls farther than she could throw her lightning. She could not hit what she could not see. At least her magic was line-of-sight and not touch-linked. She’d heard of some who could visualize what they aimed for and strike without seeing, but she could not.

This morning, the cannon had breached Ukiny’s walls. Soon the enemy would pour through the gap and bring its advantage of numbers to bear. Kallista knew her fellow soldiers would fight bravely, but the outcome was not optimistic.

“Have you decided where to post your troop?” Torchay never looked away from his view over the wall at the enemy.

Kallista sighed. That was the supposed reason for taking this little stroll into danger. She couldn’t tell her bodyguard that one more second in their austere quarters would have had her chewing holes in the furniture, even if he already knew it. “Yes. Half here—East and South. Except for Beltis. I want her fire-throwing skill with me and Adessay on the far side of the breach.”

“In the tower.”

“Tower’s too far away. On the wall. Near the breach.”

“Too close. It’s not safe.”

Kallista turned her head and looked at Torchay, at his bony, hawk-nosed visage silhouetted against the orange sky, waiting until he looked back at her.

“It’s a battle, Sergeant,” she said. “It’s not supposed to be safe.”

He gave a tiny nod in acknowledgment of that truth.

“We need to be as close to the breach as possible.” She moved to the edge of the battlements to peer over, ignoring Torchay’s hiss of displeasure. “It’s going to be up to us to slow their advance, thin their numbers as they come through.”

“You can’t do anything if you’re dead.”

“If we can’t stop them, everyone in the city could well be dead by this time tomorrow. And we haven’t enough regular troops to do the job. It’s going to require magic.”

“Just—” He broke off and took a deep breath. That wasn’t like him, to be fumbling for words. “Don’t make my job harder than it has to be, Captain. Promise me you’ll do nothing reckless.”

Kallista raised an eyebrow. “You forget yourself, Sergeant.”

“Probably. But if it means that you don’t forget yourself when the battle begins, I’ll bear the punishment.” Torchay held her gaze until Kallista had to look away.

She did have a tendency to take risks in battle. Too much caution could lose a battle. Generally her risks paid off, but once…Once, she’d nearly got the both of them killed.

“I’ll be as careful as I am able,” she said finally. “But if my action will make the difference in winning or losing, you know I will act.”

“If your lightning can turn the battle, I’ll carry you into it on my back.” Torchay paused then, so long that she glanced up at him. His gaze caught hers, held it. “But I won’t let you throw your life away on a lost cause, Kallista.” He turned away to look out over the enemy camped below. “Do you understand me, Captain? I will do my duty.”

“I never for a second thought you would do anything else.”

“Have you seen all you needed to see?”

Relieved at Torchay’s return to his normal self, Kallista tugged at the wide cuffs of her supple leather gloves and wished she could take them off. It was too hot for gloves, but a military naitan could not appear in public without them. Not unless she was about to call magic.

“Let’s go down.” She headed for the flimsy ladder leading through the trap door in the floor and below to street level. It would be simple to remove when the time came and prevent access either up or down. “I want the troop up here tonight. If we have to stumble from our billets and stagger into place half-asleep, we’ll be too late.”

Torchay didn’t answer, simply followed her down.

The streets were all but deserted, most shops already closed up, the owners and customers at home praying for rescue and hiding their valuables. The buildings near the wall showed signs of the enemy bombardment. Apparently, pinpoint targeting was not a strong suit of the Tibrans, but then with cannon, it didn’t seem to matter. The buildings here had not been of the sturdiest construction to begin with, mostly weathered wood hovels or sheds with a tendency to lean. Now some were patched with planks or canvas. Homes too near the breach in the wall had become little more than splintered debris. Kallista hoped the residents had found new shelter.

Nearer their quarters, the buildings on either side of the narrow cobbled streets at least stood up straight. More had stone walls rather than wood, and shops displayed a better quality of goods. Flags in bright colors advertised the business operating in the buildings where they flew. Here, shops of all sorts stood hip to thigh, unlike the capital where each type of business had its own street, if not its own neighborhood.

A tailor operated next door to a jeweler, next to a shoemaker, a grocer and so on. Because of the odors they generated, the tanners and the livestock markets were relegated outside the city walls. Kallista had worried about that, about running out of food during a long siege. But that was before the cannon made themselves known. The siege hadn’t been a long one.

A bakeshop along their route still displayed loaves and sweet buns on its fold-down countertop as the baker bustled about preparing to close.

“Wait.” Torchay touched Kallista’s arm, and when she stopped, he approached the baker. “How much for what you have left?”

“Can’t you read?” She jerked a thumb toward the sign. “Two buns or one loaf for a krona.”

“It’s the end of the day, your customers have gone home, and your bread was baked before dawn. You don’t advertise South magic preserving. It’s not worth that price.” Torchay spoke quietly, patiently to the baker. “I’ll give you two kroni for the lot.”

“Listen to me, soldier.” The baker spat out the word. “You got no business telling me what my wares are worth. I made these loaves with my own two hands. I don’t need magic for that. What do you make? Death? What value does that have?”

Kallista stalked toward the plump baker, her foul mood flaring into sudden temper. “What value is your life? If it weren’t for soldiers like him, you would already be living in a Tibran harim with half your iliasti dead. This man is ready to give his life for you, you ungrateful bitch, and you begrudge him a few loaves of bread?”

She knew her anger was out of proportion to the situation, but she couldn’t help it. She’d had enough self-righteous scorn from the locals who looked down their lofty faces at the soldiers defending them yet screamed for help at the first sign of trouble.

But she didn’t realize she’d removed one of her gloves until the shock of skin against skin made her jerk and stare down at Torchay’s bare hand clasping her own.

The baker’s wide eyes said she understood the threat, if not what had caused it, and she was tumbling bread into a rough sack as fast as her hands would move. “Pardon, naitan. Pardon. No offense meant.”

“None taken.” Though that was a small lie. Kallista had taken offense. And she knew better than to do so. She couldn’t change popular opinion. Her own behavior, though unconscious and unintended, had only reinforced the impression that those who served in the military were too wicked or too stupid to do anything else. Anything productive.

She considered removing her hand from Torchay’s grip and replacing the glove. But that would make her inadvertent action seem even more of a threat, withdrawn now that she had what she wanted.

“Thank you, aila.” Torchay held out two kroni. The baker waved them away and he set them on her counter. “I pay my debts, aila. I just mislike paying more than what is due.”

With the sack gripped tight in Torchay’s other hand, he and Kallista continued down the street. Around the corner, out of sight of the bakeshop, she jerked her hand free and rounded on her bodyguard.

“Are you mad? Have you lost the remaining threads of the feeble wits you might once have possessed?” Kallista held her bare hand in front of his face. “I am ungloved.”

“You hadn’t called magic. I was safe enough. I’d have been safe enough even if you had. You have more control than any naitan in the entire army. Probably in all Adara.”

Torchay’s calm unconcern infuriated her. “You don’t know that. The sparks don’t always show.”

“I know when you call magic. I don’t have to see the sparks. And I know you don’t have to unglove to do it. To do anything.”

Kallista yanked her glove back on in short, sharp motions. “Do not ever do that again. Ever. Do you understand me, Sergeant? If you do, I’ll have that chevron if I have to strip the skin off your arm to do it, and see you flogged.”

“You don’t approve of flogging.”

“For this I do. Never touch my bare hands. You know this. You learned it the first day of your guard training.”

Torchay gazed at her. She could see the words building up inside his head, battering at his lips in their desire to get past them. Other naitani had trouble with their guards getting too close, wanting more from the relationship than was possible, but Torchay had never shown any sign of the failing. Was this how it began?