Полная версия:

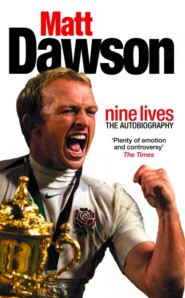

Matt Dawson: Nine Lives

MATT DAWSON

nine lives

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY

with ALEX SPINK

To my late Grandad Sam. I know you’ve been watching Grandad, and I hope I’ve made you as proud as the rest of the Dawson–Thompson clan. We never did find that eight iron!!!

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Prologue

1 Growing Up

2 Losing Ground

3 Return of the Artful Dodger

4 Heaven and Hell

(i) Lion Cub to King of the Pride

(ii) The Making of a Captain

5 Misunderstood

(i) Hate Mail, Hated Male

(ii) Striking Progress, Strike in Progress

6 Foot in Mouth

7 Going Off the Rails

8 Headstrong to Humble

(i) Bashed by the Boks

(ii) Grand Slam at Last

9 Shooting for the Pot

(i) History Lesson Down under

(ii) The Greatest Day of All

10 Celebration Time

11 A Step into the Unknown

Plate Section

Career Statistics

Index

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

Kick it to the shit-house …

That was the last thing I remember saying before the whistle blew, before I dropped to my knees, before my life changed forever.

There was no time left on the clock inside the Olympic Stadium, my very own theatre of dreams. Extra time had come and was now gone. We just had to get the ball out of play. It came to me and I flung it to Mike Catt: the ball and that less than eloquent line.

Paul Grayson, my best pal, got to me first. We shouted and screamed at each other as the raw emotion of the moment took over. I looked up into the stand to where I knew Mum, Dad and my girlfriend Joanne were sharing our joy. For a moment I was overwhelmed. It had been a long journey to the summit and the realisation that I had finally arrived stole my breath away. Almost exactly a year ago to the day I had been told my career was over due to a neck injury. Yet here I was on top of the world.

If there really is a place called Heaven on earth then I was there. I floated over to the end of the stadium occupied by the thousands upon thousands of England fans. They were singing my song, Wonderwall by Oasis. Well, of course they were. I was in dreamland. I stood in front of the bank of white shirts conducting the singing and mouthing the words along with them. ‘Sing my tune, baby,’ I yelled, as though I was on stage at Knebworth. I could see nobody I knew but I was picking people out – watching them cry, watching them hug each other – and revelling in their joy.

‘Suck it all in,’ I told myself. ‘Remember what you are seeing, remember what you are hearing. Lock away these images forever.’ It was awesome, simply awesome. It also seemed too good to be true. Because for as long as I could recall, my rugby life hadn’t been like this. For me, and those who care for me, there had been a lot of rough to go with the smooth.

I have won two World Cups and a host of titles with England but am still remembered for being captain of the side which ‘snubbed the Princess Royal’ when we didn’t go up to collect the Six Nations Cup after we had lost at Murrayfield in 2000.

I have not only won a series with the British Lions but scored the try which some say was the defining moment of our triumph over South Africa in 1997. Yet it sometimes seems I am as well known for the Lions diary I wrote in the Daily Telegraph four years later in Australia.

I have spent 13 years with Northampton, helping them to four cup finals, yet was never offered the captaincy and was instead rewarded for my loyalty by being hauled in front of an internal disciplinary committee after a nothing incident in the 2002 Powergen Final, and then effectively forced out of the club in the summer of 2004.

Through it all I have never given anything but my best, and yet it feels my motives and I have often been misunderstood. I have been called arrogant and worse. I have been upset by it, I have come close to chucking it all in. But I have also learned from it and, I think, become a better person for it.

‘Gradually,’ my mother said recently, ‘people are realising that Matthew is not the arrogant sod he appears on the pitch.’ Thanks for that, Mum. Seriously though, it has taken a lot of effort. And I admit that I have not always helped myself because I have not always let people in.

About 18 months before the World Cup I decided to do something about it. Fined by the Lions, dropped by England, in the doghouse at Northampton and out of love in my personal life, I was pretty close to rock bottom. I was completely miserable. Inspired by Wayne Smith, the new head coach at Saints, I arrived at the conclusion that if people didn’t understand me I would work harder to help them get to know me. Smithy told me that while it probably was no more my fault than that of other people, I needed to be the one who went out and made more of an effort.

A team-mate had described me as a lost soul who seemed happier away from people. Goodness knows what others were thinking. I had been neglecting my family, to the point where I could not be bothered to pick up the phone and speak to Mum and Dad and see how they were, or to tell them when I was injured. My attitude was that they would find out soon enough on teletext.

I like people to be comfortable, but I hadn’t made the effort to make those around me feel that way. Fortunately I realised before it was too late. Fortunately those around me stuck by me: my family, my friends – particularly Paul Grayson and Nick Beal – and my girlfriend Joanne. Which is why as I stood in the middle of the pitch inside the Olympic Stadium, my thoughts were not for me and for what I had achieved. The medal around my neck was for all those who had contributed to getting me there.

My story is a tale of ups and downs, of triumph and despair, of happiness and sadness, of being revered and reviled. Looking back it feels like I have lived nine lives, rather than just the one. But I wouldn’t swap it for the world; nor the people around me.

1 Growing Up

They didn’t hear the first knock. The radio was on and Dad was up a ladder. Mum was up to her arms in wallpaper paste, her stare locked on the pattern taking shape before her eyes in the upstairs bedroom.

It came again. More urgent this time. Ra-ta-tat-tat. Dad looked at Mum for a clue as to who it could be. We had only been in the house a week. We didn’t know anyone. Mum crept to the window and peered down. All of a sudden she froze.

‘Oh my God, Ron. It’s Matthew.’

Dad shot down the stairs to the hall where packing cases stood piled on top of one another, still half full after the move south from Birkenhead to Blackfield in Hampshire, where Dad’s new job had brought us. He opened the front door, and there, standing on the doorstep in front of him, was a lad wearing a motorcycle helmet. But this was no pizza delivery; in his arms was a distraught five-year-old. Me.

Our new home was at the end of a little lane on the edge of the New Forest. The day was warm and bright, and my sister Emma and I had been playing on our pushbikes up and down the leafy lane. You could not imagine a safer place to be. At least until the scooter hit me.

The shaken rider handed me over to Dad. I had a broken collarbone and a gashed head. He was all apologies, insisting I had come out of nowhere and he’d had no time to react.

By now Mum, who’d followed Dad down the stairs, was frantic with worry. As we were new to the area neither of my parents knew where the hospital was. Still, they laid me across the back seat of the car and set off, hazard lights flashing and Dad waving a white handkerchief out of the driver’s window. It must have been quite a sight, as must the expression on Dad’s face when we arrived at the local hospital in Hythe to find a notice pinned to the entrance which stated that they were shut and that we needed to go to Southampton, a further half an hour away.

We laugh about it now, particularly at the memory of the lad on the scooter returning to our house a week later to present me with a Tufty Road Safety board game. But it was not remotely funny at the time. My career could have been over before it had even begun.

I was born to Ron and Lois Dawson on 31 October 1972, and almost from the day I arrived kicking and screaming into the world at Grange Mount Hospital in Birkenhead I was a worry to them. They did not know then that I would go on to have lumps knocked out of me for a living, but based on the early evidence they might well have guessed. As a toddler I never used to walk anywhere; I was always running around on my toes and falling downstairs. One day I tumbled into a wrought-iron gate and emerged with a lump on my head and the clearly visible imprint of one of the gate’s bars. Another time, I got a wine gum stuck in my throat and stopped breathing.

Dad worked shifts at Mobil Oil, and my problems always seemed to come in the evening when he was away on the two till ten beat, so it was Mum who often had the traumatic task of scooping me up in one arm while using her free hand to point Emma, three years older than me, in the direction of the car for yet another mercy dash.

He was at work the day I performed a disappearing act which so alarmed Mum that she called in the police. Mind you, I was only two and a half at the time. She had left me playing barefooted with my first girlfriend, Elspeth, on a patch of grass at the end of the cul-de-sac in which we lived. But by the time she next turned round to check on us we’d decided to walk to our nursery school, through the estate and up and over the main road using the footbridge. Mum swears she realized we were missing within seconds of us leaving. Whatever the truth, she had the police around pretty smartish. They searched our house and then Elspeth’s before combing the neighbourhood, eventually spotting the two of us walking hand in hand on the other side of the main road.

Mum nearly suffocated me with her hug when she got me home. Then she lost it a bit. She was embarrassed that so many policemen had been called out to look for me. And there was another reason for her red face: her dad, Sam Thompson, was a chief inspector with the Birkenhead Police. The following day, Grandad went into work to find a note pinned to the noticeboard with his name on it: ‘Would C.I. Thompson please keep his grandson under control and stop providing extra work for half the Birkenhead police force!’

It didn’t get any easier for Mum and Dad as I grew older. Two days before my seventh Christmas Mum was wrapping presents in the upstairs bedroom when I charged through the door with my best friend, Spencer Tuckerman, in tow to ask if we could go sledging on a snow-covered slope down the road. So keen was Mum that I didn’t see my unwrapped gifts that she nodded straight away, without thinking through the possible consequences. Half an hour later, Spencer’s mum was on the phone. ‘Lois,’ she said, ‘bad news I’m afraid. Matt’s had an accident. His face has been run over by a sledge.’ Mum arrived at the scene of the head-on smash to find Mrs Tuckerman crouched over me trying to hold my nose together and staunch the flow of blood. I was once again rushed to Casualty where I had to have 16 stitches.

In a desperate attempt to keep me out of mischief, if not harm’s way, Dad turned to rugby union, the sport he had played as a centre for the Old Boys team at Rock Ferry High School during his younger days in Birkenhead. He took me along to the Esso Social Club where a shortage of lads of my age resulted in me being thrown in with the under-10s. I was very small for that age group, so in an effort to make me look mean Dad wrapped a towelling bandage round my head. They then stuck me out on the wing in the hope that I wouldn’t get involved too much (Mum still thinks that’s the best place for me during a match).

I enjoyed the rugby, but I also loved football, which I started playing when we moved to Marlow in 1980, and it was the only sport on offer at the Holy Trinity primary school. My grandfather on Dad’s side had played for Garston Gas Works, later to become Liverpool. I supported Everton. I continued to play rugby on Sundays at Marlow RFC, where Dad coached me (he’d initially just come along to watch, but after a while standing on the touchline someone asked him to help out; he agreed, he worked hard for his certificates and coached for the next 11 years), but football was my main love and before too long I was picked up by Chelsea Boys. A Chelsea scout had seen me and Spencer playing locally for Flackwell Heath, and the pair of us were invited to play for the baby Blues. To this day, Spencer’s dad, Alec, is convinced I would have gone all the way had I stuck with it. I was a right-back, ‘fearless yet quite skilful at the same time’ in Alec’s opinion – which, of course, I value. The reports coming back to my parents also suggested I had a good chance of making it. I was very dedicated and I wanted it badly.

But by that time I had left primary school and started at the Royal Grammar School, Wycombe, where rugby was the main sport, and I had only played a handful of games for Chelsea when I got the nod from RGS that I needed to concentrate on my work and rugby rather than go to Chelsea twice a week. I was reluctant to give up football, though, even when Dad told me I had more chance of making it in rugby because ‘every kid wants to play football’.

As far as I was concerned, it wasn’t as simple as that. I was a typical teenager and I wanted to break away from Dad’s rugby coaching. We got on, but we were often at each other’s throats. ‘God, why are you always having a go at me?’ was the sort of attitude I’d quickly developed. He worked so hard, getting up at five o’clock every day to fight the M25 en route to either Heathrow or Gatwick and not getting home until seven or eight o’clock in the evening. And then he would have me to contend with. I had no appreciation at all for what he was trying to do for me. On Sundays I just wanted to enjoy myself playing, but he was the coach and we did things his way. It always seemed to me that he spoke to me in a way he didn’t to the other boys. Whenever I’d had enough of it I would walk off and tell him to leave me alone; he would then get angry with me. Football, however, was a totally different experience. Mum would come and watch while Dad was busy with the rugby team.

My cause with Dad was not helped when I was arrested for petty theft. I was kicking around with a dodgy bunch of boys who were teaching me bad habits. One was that you save money if you don’t pay for goods. So there I was in a shop on the high street in Marlow, stuffing one of those party streamer sprays into a pocket in my jeans, when I felt a tap on my shoulder. The two lads I was with bolted out of the shop and got away but I was banged to rights. The police were called, and I was ushered into the back of their car and driven all of 200 yards down the road to the police station. I thought the world was going to end. Mum, who was working part-time at the local post office, got the call to come and get me, and I felt so ashamed that I could not look her in the eyes.

I was given only a warning by the police, and was grounded by Dad, but neither hurt me as much as the reaction of Mum, the daughter of Chief Inspector Thompson, someone I had an unbelievable amount of respect for. ‘What is your grandfather going to think?’ she sobbed. She made me feel about two feet tall. In fact, the experience would haunt me for years. When I turned 18 I applied to join the police force but panicked when the application form asked for any previous convictions. It was only when Mum and Dad assured me that I didn’t have a criminal record that I put it in the post. (In the end I was turned down on medical grounds as I had just undergone a knee operation and they felt I wasn’t fit enough.)

Being grounded was an annual feature of my childhood. I would take my summer exams, my report would follow me home on the last day of term and my first week’s holiday would be spent paying for my poor results alone in my room.

‘This is not good enough, Matthew,’ Dad, it seemed, always said on opening the envelope. ‘You’re grounded. Go to your room.’

‘Right. Whatever.’

I was under orders to read for an hour each morning, but that was way beyond my powers of concentration. So I waited until my parents had both left the house for work and then jumped on my bike and went to meet my mates. It required military precision to get back home, return the bike to exactly the same position I’d found it in the garage, then to jump onto my bed and open the book 50 pages on from where I’d left it before Mum’s car turned into the drive.

As I got older I gradually began to realize what a fool I was being, in my rebellious attitude towards Dad in particular. He was my biggest supporter; nobody wanted better things for me than him. But that realization took time to dawn on me; initially I agreed to go back to rugby only if he stopped coaching. With time, though, I welcomed his support and indeed sought his approval, even if his vociferous backing wasn’t to the liking of everyone. In assembly one day at RGS he was named and shamed for over-exuberance on the touchline during a school match. I was so proud of him. I thought it was hilarious. It was the one and only time my name was read out during assembly without me being told off as a result. On another occasion he was warned for shouting at a referee. He liked to tell them why they were wrong (and you wonder where I got it from!).

When I played rugby during my teenage years I could always hear Dad’s voice. Whenever I passed the ball from the base of a ruck I’d hear him bark, ‘Follow the ball!’ I would have thought something was wrong had I not been able to pick out his voice. And, being a coach, his enthusiasm extended beyond the playing field, so keen was he that I got the most out of myself. When I was selected for England 16 Group Dad felt I was too much of a couch potato at home, so he organized ‘training’ sessions in our back garden. He would try to get me doing press-ups and shuttle sprints. I would go out for five minutes to humour him, then return to the sofa. Happily, certainly from Dad’s point of view, I became more committed once I turned 17. Two or three times a week I would go on an eight-mile run, up to the M40 roundabout, back down a little lane, then all along Marlow Bottom. I’d get home from school, change into my kit and set out. The best times were always in the summer when I could wear a vest and run past the girls coming home on the school buses. It was both a pleasure and a pain.

Dad wasn’t the only guiding light during my formative rugby-playing days. From the age of 13 through to the first XV my coach at RGS was Colin Tattersall, and he had a huge influence on my game. We were a successful school side, losing only two or three games a season, but when I was in the sixth form we played against hardly any public schools. They wouldn’t take our fixture because we were a state school, albeit a very good one with a strong set-up. That has since changed. RGS now plays against the likes of Radley, Millfield and Harrow, but at that time we only got to play against those sides in the Daily Mail Cup.

It was probably a good thing that I showed promise in sport because my academic accomplishments were average, as most of my tutors never tired of telling me. How I ever got into the Royal Grammar School in the first place I will never know. We had to take a 12-plus to secure a place, and how I passed that remains a mystery to me. Me and exams don’t get on. To this day I hate the words ‘exam’ and ‘test’. I managed to scrape four GCSEs first time round, adding another four later on, but I failed all my A levels, primarily because I was away playing with the England 18 Group for six to seven weeks during the lead-up to the exams. I came back not much more than a week before my first paper, so it was hardly perfect preparation. And believe me, I needed perfect preparation. Fortunately, the school allowed it, but mine was a poor show academically. It’s not something I’m proud of, but at that time of my life I was just not tuned in to working, be it homework or writing essays. All I wanted to do was play rugby. Or football, or snooker, or golf, or cricket …

I played all five matches for England under-18s in that 1990–91 season, forming a half-back partnership with Epsom’s soon-to-be-Irish Paul Burke. We narrowly lost to the touring Australians 8–3 at Twickenham (no disgrace as they won all 12 matches they played), but we beat Ireland, France and Scotland in successive matches, conceding only 16 points in the process. However, our campaign ended on a depressing note in Colwyn Bay when we lost to a Wales side that had been thrashed 44–0 by the Aussies. We had seemed on course for a Junior Grand Slam when we led 10–4 well into the second half, but we let them back in, gifted them a really soft try and Chris John’s boot did the rest. Wales won the match 13–10 and with it the Triple Crown.

The following season I moved up to the England under-21 side, leaving behind scrum-half Andy Gomarsall to captain England 18 Group to the Junior Grand Slam we had missed out on. My debut came at centre in a 21–21 draw with the French Armed Forces in a match at Twickenham played as a curtain raiser to the Pilkington Cup final between Bath and Harlequins.

It was my first game at Headquarters, and Mum and Dad were in the stands. They have barely missed a game since, a habit born out of Mum’s fear that she should always be on hand in case I suffered a bad injury. It dates back to when she used to make the sandwiches at Marlow. If any of the kids were injured she would accompany them to hospital in the ambulance, and the first thing they would always say to her was ‘I want my mum’, and that stuck with her. I know she’ll be an awful lot happier when I retire from rugby. She finds the whole experience torture, and it has never become any easier for her. But she feels that if she misses a game, I’ll get injured. I can only guess at the number of games she and Dad have missed throughout my career across the world – less than 10 certainly. I am unbelievably lucky, because although the majority of parents support their kids, very few do to the extent mine have. Dick Greenwood, father of Will and a former England player and coach, once told Mum that he knew exactly how she feels. ‘It’s like a little spotlight follows Matt around the field, isn’t it, Lois?’ he said. He couldn’t have put it better. Because of the position I play I am often trapped under piles of players while play carries on. Mum keeps watching me rather than following the ball, which she leaves to Dad. She feels that if she takes her eye off me something bad will happen. She doesn’t usually have a clue about how the game is going, but if I go down because I’ve got a fly in my eye, she’ll be the first to know.

All this support at times made for a difficult relationship between me and my sister. As kids, Emma and I lived very different lives. Socially we had different sets of friends: she went to a school in Maidenhead and had friends in Marlow whereas mine tended to be more in High Wycombe and Aylesbury. She saw her brother playing for England and getting the odd write-up in newspapers and her Mum and Dad following me everywhere. Looking back, it must have been hard for her, and I can fully appreciate her frustrations. I’m sure she would have welcomed some of that attention herself. It was only later, after we had both left home, that I consciously tried to make up for lost time. Emma is now married to Martin, with two children, Daniel and Ellen, and we often meet up for barbecues.