Полная версия:

Roots of Outrage

JOHN GORDON DAVIS

ROOTS OF OUTRAGE

COPYRIGHT

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1994

Copyright © John Gordon Davis 1994

Cover photograph © Shutterstock.com

John Gordon Davis asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007574391

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2014 ISBN: 9780008119294

Version: 2014-12-16

PRAISE

‘John Gordon Davis has hit the jackpot again. Highly recommended … this epic volume cries out to be filmed.’

Natal Mercury

‘Captures perfectly the emotions, hopes and fears of a very explosive yet exciting time. It is a story so well told you can smell and feel Africa on every page.’

African Panorama

‘A sweeping history, politically questioning and charged with passion.’

The Star

‘Great holiday reading. This is a huge saga of history, politics, romance and adventure set against the turbulent background of South Africa.’

Eastern Province Herald

‘North and South and Gone With the Wind wrapped into one. A great read.’

Sunday Tribune

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to my wife, Rosemary

EPIGRAPH

The story of South Africa is real. The characters, with obvious exceptions, are fictitious.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Epigraph

Maps

Prologue

Part I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Part II

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Part III

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Part IV

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Part V

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Part VI

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Part VII

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Part VIII

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Part IX

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Part X

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Part XI

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

Chapter 84

Part XII

Chapter 85

Chapter 86

Chapter 87

Chapter 88

Chapter 89

Part XIII

Chapter 90

Chapter 91

Chapter 92

Chapter 93

Chapter 94

Part XIV

Chapter 95

Chapter 96

Chapter 97

Chapter 98

Chapter 99

Chapter 100

Part XV

Chapter 101

Chapter 102

Chapter 103

Chapter 104

Chapter 105

Chapter 106

Part XVI

Chapter 107

Chapter 108

Chapter 109

Chapter 110

Chapter 111

Chapter 112

Part XVII

Chapter 113

Chapter 114

Part XVIII

Chapter 115

Chapter 116

Chapter 117

Chapter 118

Keep Reading

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

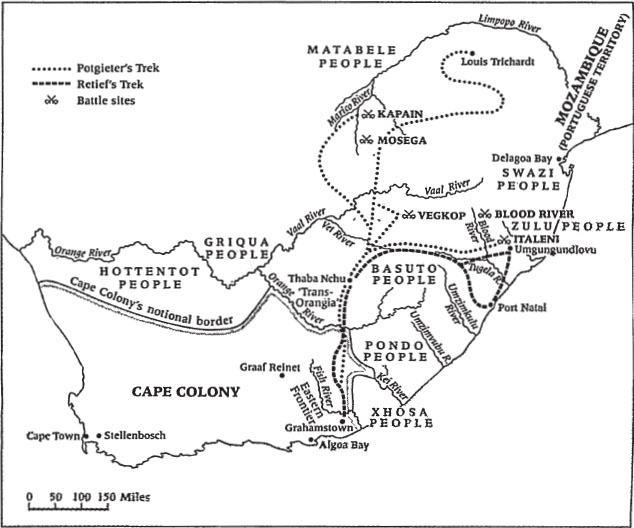

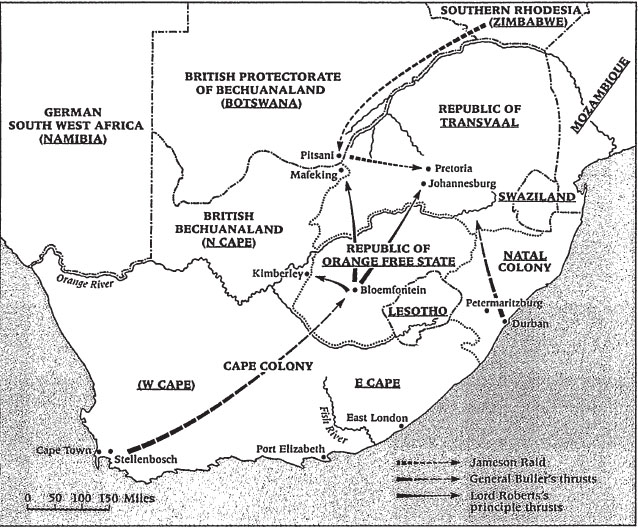

MAPS

Southern Africa at the Time of the Great Trek

South Africa at the time of the Boer War, 1899

(Modern names of provinces/countries are underlined)

PROLOGUE

The gallows stood ready, silhouetted. These hard, rolling hills of the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony were soaked in the blood of the Kaffir Wars, and today more blood was to be spilt at the execution of the five ringleader Boers of the Slagter’s Nek rebellion – at the very place where they had taken the oath to drive the British into the sea.

The hangman, who had journeyed up from the coast, had brought only enough rope to hang one man at a time, so the magistrate had acquired more, but unbeknownst to everybody it was rotten. Now five nooses dangled, and gathered around were the relatives of the condemned, the other rebels who had been sentenced to imprisonment and the Dutch farmers from miles around who had been ordered to attend to witness how seriously the British took rebellion. And now, from the direction of the military post, came the beat of drums, and the wagon bearing the condemned.

The drummers slow-marched. Slowly they advanced up the rise to the gallows. The condemned men climbed down off the wagon and mounted the scaffold. One after the other, the hangman tied their ankles, slipped the nooses over their necks. When all was ready, the Reverend Harold led the assembly in prayer. The magistrate ordered the drums to roll: softly, then louder and louder. The plank was kicked away, the men plunged into their death-fall, there came the dreadful wrench on their necks, and four of the ropes snapped.

The condemned men lay writhing in the dust, choking, as pandemonium broke out all around them: the shrieks of joy that the hand of God had intervened, people rushing to the struggling men, wrenching loose the nooses, the priest in the midst of them gabbling his prayers. Then the magistrate bellowed above the uproar: ‘Bring more ropes!

The uproar redoubled, the priest in the forefront – ‘God Himself has intervened!’ The magistrate had to shout at the top of his voice that it was not within his power to grant pardons.

By the time the horseman came galloping back with more ropes order had been restored. The condemned were clustered under the gallows in the arms of their wives and friends, surrounded by a ring of soldiers. While the hangman rigged new nooses the priest led the emotional people in prayer again. Then the condemned men sought permission to sing a hymn. This was granted, and the tearful cadence rose up. Then one of the condemned asked permission to say a few last words, and in a shaking voice he urged his brethren to heed his unhappy fate. They mounted the scaffold again. The magistrate ordered another roll of drums. The platform was kicked away.

This time the ropes held: the men hung, their eyes bulging and their tongues sticking out, excrement dripping down their kicking legs, and a howl of anguish went up from the people.

King Henry the Navigator called it the Cape of Good Hope, for he was sure it was the sea-route to China, but despite its mercantile importance this southern tip of Africa lay unoccupied until, in 1652, the Dutch East India Company established a small revictualling station for its ships there, called Cape Town. The Company had no intention of colonising the interior, but within a hundred and fifty years Dutch farmers had, in defiance of Company edicts, wandered six hundred miles along the rugged coastal hinterland with their cattle, building mud and thatch homesteads, then wandering on after a while. They were called Trekboers, and a new language evolved, a bastard Dutch called Afrikaans.

Theirs was a good life, called the Lekker Lewe, of limitless land, adequate slave labour and security, for they met no Caffres – as black men were then called – the hinterland being empty but for small bands of nomadic Bushmen who were soon driven out. But finally they came to the big river called the Fish, and beyond were many warlike Caffres, the Xhosa, and they were also cattle men.

The Company forbade the Trekboers to cross the Fish River, to have any contact with the Xhosa. But there was always cattle thievery, followed by raids to recover the cattle (and probably a few more besides), and by the time the British occupied the Cape in 1806 to protect her Far Eastern trade against Napoleon there had already been three bloody, full-scale ‘Kaffir’ Wars.

The British were mighty unwelcome amongst the rough and ready Boers. And with the Redcoats the Age of Enlightenment arrived at the wild and woolly colony, in the form of the London Missionary Society and British justice. The missionaries blamed the frontiersmen for the Kaffir Wars, and the British magistrates busied themselves with cases of mistreatment of slaves and servants, which was deeply resented. A handful of Boers plotted a rebellion after one of their number was shot dead resisting arrest, and their leader stole across the Fish River to make a treasonous pact with the dreaded Xhosa: Join forces with me, together we’ll drive the British into the sea and then divide the land between us. The wily Xhosa chief declined. The rebellion was quickly put down by the redcoats, but the British took treason seriously and their ringleaders were sentenced to death. Their ghastly public execution at Slagter’s Nek followed.

It is bitterly remembered to this day. And history was to repeat itself.

At about the same time, far away on the lush coast of south-east Africa, there arose a warrior king called Shaka, who welded together the nation of the Zulus, the ‘People of Heaven’. The Zulus made war on neighbouring tribes, who fled and made war on their neighbours, all killing and plundering for food. This period was called the Mfecane, which means the ‘crushing’. It was a time of chaos, the veld blackened with burnings and littered with skeletons. One of Shaka’s generals, Mzilikazi, rebelled and led his people up onto the highlands, making mayhem more terrible, and established a new nation called the Matabele, which means the ‘destroyers’. The dislocations pressed upon the Xhosa, who had no place to go but across the Fish River into white man’s land; the cross-border thieving, raids and counter-raids got worse.

The government decided to settle thousands of British immigrants on farms along the Fish, to form a buffer zone, and forts were built; but the thieving continued and in the next decade there were two more full-scale wars. The missionaries blamed the frontiersmen and raised a furore in London, so the imperial government hesitated to act decisively against the Xhosa. And then the missionaries forced the repeal of the Vagrancy Laws, so now blacks roved the frontier at will, thieving. And then the Abolition of Slavery Act was passed: all slaves throughout the British Empire would be emancipated at midnight 31st December 1834. This would wreak great hardship on the Cape’s frontier. On Christmas Day 1834, six days before the slaves were to be freed, the Sixth Kaffir War broke out. It was the bloodiest of all.

As the frontiersmen celebrated Christmas, there was a massive eruption of Xhosa warriors across the Fish, burning, killing, plundering. They swarmed over thousands of square miles before they were driven back across the Fish by British troops and frontier commandos. It was the costliest war in the frontier’s bloody history; eight hundred farms destroyed, hundreds of thousands of cattle stolen. It took six months to drive them further back across a distant river, for the British commander intended to create a militarised cordon sanitaire to keep the races apart. There was rejoicing on the frontier, for it looked as if a new order was being ushered in at last.

But it was not to be. The missionaries blamed the frontiersmen for the war, and so the imperial government ordered that the newly annexed buffer zone be abandoned. It seemed towering folly: the thievery and wars would continue. There was outrage on the frontier. And then the news came that the British government had reneged on its promise to compensate slave-owners fairly: the sum of three million pounds that had been allocated for the purpose was reduced to one million, and would only be given to those who journeyed to London to claim it.

The sense of outrage redoubled on the frontier, amongst Boer and Briton alike, for who would leave his farm unprotected from marauding Xhosa for a year to make an expensive journey to London?

And so the Great Trek began. And Ernest Mahoney, from New York, enters our story.

The Great Trek was not a sudden, stormy mobilization of an angry people, as romantic chroniclers like Ernest Mahoney have suggested, it was the slow culmination of bitter debate that had been going on since the terrible Slagter’s Nek hangings: the thievery, the repeal of the Vagrancy Laws, the ‘ungodly’ attitude of the British towards master-and-servant relationships, the injustice of the missionaries, the Abolition of Slavery Act which defrauded them, the terror and devastation of Kaffir Wars, the British government’s refusal to fight them decisively. The Great Trek was a gradual consensus of people who had been bitterly tried, God-fearing folk who knew little other than the Bible and the gun, who had finally had enough of their incompetent, duplicitous government. In part it was the old trek spirit of their forefathers coming back, the quest for pastures new and the Lekker Lewe, but more important was the resentful determination to set their world to rights. One after another the hardy Boers packed up their wagons, rounded up their herds and set off. Out of the mauve hills of the frontier they rolled northwards, up into the highveld of Trans-Orangia, to find their Promised Land.

It was in Piet Retief that the people found their Moses. It was he who published the Voortrekker Manifesto:

… We despair of saving this country from the threat posed by vagrants ... nor do we see any prospect of peace for our children … Be it known that we are resolved, wherever we go, that we will uphold the just principle of liberty; but whilst no one shall be in a state of slavery, it is our determination to maintain such regulations as may suppress crime and preserve proper relations between master and servant … We shall not molest any people, nor deprive them of the smallest property; but, if attacked, we shall consider ourselves fully justified in defending our persons and effects to the utmost …

It was a profession of faith, an enunciation of constitutional principles for a democratic Boer republic. Much of the turbulent story of South Africa is a betrayal of that manifesto.

Enter Ernest Mahoney of New York, sent thither by the Harker-Mahoney Shipping Company to investigate trading opportunities in this opening-up of the African hinterland. A hundred and twenty years later, when Ernest’s great grandson, Luke Mahoney, read his forebear’s journals of that epic time, he could visualise the meeting of shareholders in New York, the rotund old chairman, Ernest’s grandfather, saying:

‘The Mahoneys were amongst the first to transplant the principles of our magnificent American Revolution across the oceans ... Amongst the first to seize the unspoilt virtue of our frontier heritage and reject the wiliness of the Old World, “its useless memories and vain feuds”, amongst the first to shun the tawdry lures of Europe and export our American Enlightenment by the adventurous prows of the Harker-Mahoney clippers to replace wars and so-called diplomatic treaties with the benign embrace of commerce … the first to join with those Massachusetts poets in their cry:

Preserve your principles, their force unfold

Let nations prove them and let kings behold.

EQUALITY, your first firm-ground stand;

Then FREE ELECTIONS; then your FEDERAL BAND.

‘We were amongst the first to see that political happiness would eventuate throughout the world from the simple principle of free oceans, free trade, and the free dissemination of American inventiveness by Yankee vessels, and that, in return, the world would unfold its treasures … The Mahoneys were amongst the first to turn America’s eyes to the Pacific, and to Africa, to probe dark regions of alien religions which would, through our worthy commerce, fall to the influence of our Enlightenment … And we all know what the result is: Harker-Mahoney has, without firing a shot except in self-defence, an empire upon which the sun never sets … And now there is a new frontier for Harker-Mahoney to add to their empire, brethren shareholders! It is the hinterland of southern Africa!

‘“The hinterland”? you ask. We have traded profitably with the Cape of Good Hope for years, but how do we penetrate the hinterland? Ah … It is being penetrated for us by the Dutch Boers, just as our west is being opened up by our pioneer wagons! Whole new lands that will one day stretch to the Nile, vast new untapped markets for our goods, vast new resources, lands bigger than the whole of China …’

And so now here is nervous Ernest Mahoney, twenty-two years old, lanky, wan – a graduate of a Presbyterian seminary but feeling unable to take holy orders because of lusts of the flesh – disembarking with a big bagful of silver dollars, buying two horses, hiring a Dutch guide (paying twice what he should and thinking it cheap), setting off timidly into the wilderness to spread the American Enlightenment through worthy commerce. Ernest riding up into the highveld, overtaking Boer wagon trains, eventually coming upon the high mountain called Thaba Nchu, the foregathering place. The hundreds of wagons outspanned, the thousands of Boers waiting for their leader, Hendrik Potgieter, who had trekked on to the north to explore, for Piet Retief to come up from the south. There is Ernest fearfully riding on north with his guide to look for Hendrik Potgieter’s wagon train, following his tracks; the veld is littered with evidence of the Mfecane, whitened skeletons, burnt huts. Ernest eventually finds Potgieter and his people feverishly preparing for an imminent attack by Mzilikazi, lashing their wagons into a circle, stuffing thorn branches into the gaps. And so Ernest, four weeks in Africa, never having fired a shot in anger, who just wants to get the hell out of this land, finds himself plunged into one of South Africa’s most famous battles. And he meets Sarie Smit, the feisty Boer girl assigned to him as a loader because she speaks English.

The Battle of Vegkop. The veld black as ink with five thousand of Mzilikazi’s warriors loping across the veld chanting Zhee Zhee, encircling the wagons, sharpening their assegais, humming, humming for hours until Potgieter tied a red rag to a stockwhip and waved it above the wagons as a challenge. Then their terrifying battle charge, thousands of glistening warriors hurling themselves at the laager, stabbing, slashing, hurling, the wagons shaking under their tumult midst the cacophony of the trekkers’ muzzle-loaders, the smoke and stink of gunpowder. And there is Ernest, sick-in-his-guts terrified, blasting straight into the savage faces through the thorn branches, thrusting the spent gun at Sarie and grabbing the reloaded one she thrust back – bang – grab – bang – grab – bang – There is sweaty Sarie Smit and her mother pouring the powder down the hot muzzles, ramming in the lead with a wad of cotton on top, thrusting the gun in Ernest’s trembling, outstretched hand – bang grab bang … For hours the cacophonous battle rages, and the bloody black bodies are piled high around the laager before Mzilikazi’s warriors withdraw, round up all the voortrekkers’ thousands of cattle and drive them off northwards. Potgieter sends horsemen galloping back to Thaba Nchu to call for oxen, and Ernest volunteers to ride with them. It is regarded as a courageous offer, for more Matabele impis may be waiting, but Ernest just wants to get the hell out of there. And when, eight days later, he arrived at Thaba Nchu, he would have kept going, heading south to the faraway sea to take the first ship back to America, except that no way was he going to ride alone through this fearsome country.