скачать книгу бесплатно

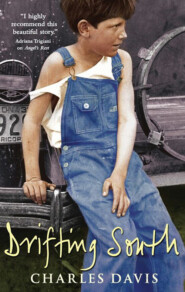

Drifting South

Charles Davis

Shady is the town where I grew up in every way a young man could, where I saw every kind of good and bad there is to see.Everybody found their true nature in Shady. In a single day, Benjamin Purdue lost his family, his love, his freedom and even his name for reasons he’s never known. Now Ben, the boy he used to be, is dead. And Henry Cole, the man he’s become, is no one he would ever want to know.With only a few dollars in his pocket, Henry journeys back to the dangerous town where it all began. The only place he’s ever called home. As he drifts southward, he gets closer to the beautiful woman whose visit to Shady all those years ago ended in a killing. A woman who holds the keys to his past…and his future.

Charles Davis is a former law enforcement officer and US Army soldier. In 1999 he moved from the coast of Maine to North Carolina, rented a beach house, got a part-time job as a construction worker, and began writing his first novel. The author currently lives in New Hampshire with his wife, son and dog, where he is working on his next novel. Find out more about Charles at www.mirabooks.co.uk/charlesdavis

Drifting South

CHARLES DAVIS

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

Prologue

I came to know that lost place the way only a select few did. I was born there, a month too early on the scrubbed pine floor of a whorehouse in the spring of 1942. Ma’s first sight of me was by lantern light. She said I glowed like sunrise and I was the most beautiful thing she’d ever seen. Conceivings could naturally be expected on any given moment in Shady, but few birthings. Ma told me I came sudden and ready to meet the world on a Sunday at midnight and I wasn’t about to be born in a bed where business was conducted. Especially on a Sunday.

“Bad luck,” she said.

Ma was a charm-carrying believer in astrology, signs, luck, and evilness of all shapes and varieties. She believed in goodness, too, and a life after this one that was full of that goodness. And she also believed in a thing that she could feel more than she could see, that she called “the mystic.” It’s right there living alongside us. And sometimes among us, she said. Ma always did have a superstitious nature and peculiar beliefs about so many things compared to most. She was pretty and graceful with curly black hair, and she was a whore and had to be a hardworking one because she believed in keeping her children fed.

We all had fathers of course, but we never were sure who they were as Ma never got much help raising us. I didn’t think she knew who our fathers were, either, by the way she kept trying to hang each of us around the neck of about every man who’d blow through Shady Hollow. They’d always leave for good or try to once they got wind of what her intentions were.

People who lived and worked in Shady Hollow just called it Shady. Wasn’t but twelve dozen of us or so at any one time who had a bed to sleep on that wasn’t being paid by the night for. Most of the faces in Shady changed quicker than day and night coming through the same window. But some took root for years and years for their own good reasons, which weren’t nobody’s business, Ma said. And she told me it was none of my business why we lived there, either, or why she did what she did for a living, when I asked her one time. Ma was only sixteen years older than I was, but she always seemed a lot older no matter what age I was at, even though she didn’t look it.

Shady Hollow lacked a lot of things, like electricity and flushing toilets and a post office, but a person who had nothing in the world but a stretched-out hand never got too cold or too hungry.

Shady never became a real town and the name never was on any map. If you did hear about Shady Hollow in some rambling story from a man or woman you wouldn’t be apt to believe anyway, you’d think the place never did exist. But it did. It was the realest place I’ve ever lived and, even after all of those years I spent in prison, that’s saying something.

Ain’t many places more real than a prison.

From the stories I heard over and over as a boy, Shady Hollow got started in a two-story barn in 1861 by a man named Luke Ebbetts. He named his place “The Establishment on the Big Walker,” and he sold homemade whiskey and hired a whore from Tennessee who soon had more work than she could handle shaking the rafters in the loft.

Luke believed he could make a sizable profit providing to soldiers what the Blue and Gray armies wouldn’t provide for them. Things like liquor and good cigars and women and a hot bath and photographs of them standing tall and fierce in their brushed uniforms and decent hot food and music everywhere. You could hear music in Shady day or night from the earliest times, they say. Night it was louder.

I’m not sure if Mr. Ebbetts would put the things I listed in the same order that I did per a man’s necessity, but he made sure all was aplenty and more to suit any man’s tastes and size of pocketbook.

Luke was a rebel through and through, but he was a businessman above all and he welcomed any uniform wandering into Shady as long as those boys didn’t ask for credit and stacked their weapons when they showed up with their powder dry and ready. Those long rifles would be stacked quick or there’d be shotguns pointed at them. The soldiers who risked coming to Shady Hollow weren’t shy of a fight for certain, but they’d do what Luke said, because the one thing they didn’t come for was to hurl lead at one another. They’d had enough of that, and that’s why they’d walk away from their guns peaceable for a day or two and sometimes even have a drink with their enemy before they’d go to killing each other again on some battlefield up on the Shenandoah.

It wasn’t long before a couple of men who worked for Luke saw how he was making more Confederate and U.S. money than he could bury in canning jars. With his permission, they soon built their own leaning shacks with hand-painted signs atop them, sold whatever things were needed to keep the place running, and hired their own whores who kept more tin roofs shaking. Luke got his cut from all of it.

Before the end of the war, flatboat drivers were braving boulders and swirl holes to float pianos and piano players into Shady, and the rest is pretty much what it came to be—a haphazard outlaw settlement tucked deep into the Blue Ridge Mountains of Southwest Virginia.

Deep. Deep in those mountains.

All sorts came to Shady Hollow once word of the place started drifting out of those foggy hills. Coal miners. Timber workers. Rich northern college kids with old money rearing to depart their new pockets. Gamblers. Orchard pickers. Foreigners. Roamers. Murderers. Thieves. Forgivers. Saviors. And the unrepentant, those rarest of few who in their final dying act would find the will to hold up a shaking middle finger for whoever could see it, and take note of it, one last time.

And politicians and railroaders and mill workers and carpetbaggers and just generally people looking for a good time or those who’d lost their religion or way in some other life.

Fugitives and fortune seekers all of them were, winners and losers, adventuresome folks who’d heard about it and some who came from thousands of miles away. The strangest and the bravest and the most curious of the needy or greedy or forgotten or unwanted seemed to collect there. Good and bad they were, most often a troubled mix of the two things churning away in the same person.

And women were among them. Shady was full of women. Most didn’t stay long like Ma, but they were always coming in and out. They were all sizes and shapes, showing up barefoot and hungry most of the time, a few with a dirty baby nursing on a tit and a screaming little walker in hand.

But some gals made up all fancy would come to us riding tall on a hungry horse or, later, sitting in a new shiny automobile running out of gas with a smile on their face that anybody from Shady could see right through. They had life growing in their bellies, and like everybody else, I reckon they all hoped what they needed to find was there. And one thing for sure, everybody found their true nature in Shady Hollow, because it was the sort of place where a person’s true nature was bound to run into them right quick.

Anyway, Shady wouldn’t have been what it was without its women—it would have been one mean miserable place for sure then—and I reckon the place probably needed children, too. It’s where I grew up.

During my time there, the churchgoers scattered around that part of the Allegheny wilderness country called Shady Hollow “No Business,” because they said no man nor beast had no business going near there. The faithful would proclaim in their town meetings that the government should destroy Shady because there was evilness just a day’s walk from their back pasture fences. The Shady elders would send spies to their gatherings, and we’d soon get secondhand tellings of all the goings-on.

There’d be family men standing up, quoting the Holy Bible in the strongest voices they could muster after their church visits, all of them worn down from trying to save our souls.

But as I’d come to learn already, what some people would say or pray in church on a Sunday morning, and actually do in Shady Hollow on a Saturday night, were two different things.

And you could put a fair wager on that about every time, if you could find somebody foolish enough to take such a bet. Which weren’t likely.

In those church meetings, some of the folks with the loudest voices would come back alone when they could get away with it unnoticed, and they wouldn’t be thumping on a Bible. We figured they had butter and egg money in their pockets, and God sound asleep on one shoulder and the devil picking a five-string banjo on the other. And they’d come back again and again.

We’d welcome them with their stern or bending ways as it suited them, politics and people and religion being the way they are and always have been. So we were a tolerable lot in Shady, even with the Bible toters.

My whole world my first seventeen years, save one trip not so far by miles but a long distance by all other measures, was that curved riverbank with shacks and stick buildings lining both sides of a one-lane road that was mostly mud, tire tracks, horseshit and changing footprints.

Besides the occasional car coming in or out, people rode horses and mules and walked and even peddled bicycles through the mountain country to get there, because the law was so bad about stopping anybody coming in or out on the only dirt road that led to Shady. And some of those yahoos were lazier at thieving than we were by the way they’d hold up folks leaving and charge them for this or that crime, before telling them that if they paid their fine in cash on the spot, they’d be let go and there wouldn’t be a jailhouse stay or court hearing at the county seat of Winslow.

And the fine was always however much money the law could find on them. They’d take watches and rings, even wedding bands for payment, too. When they started taking vehicles and sending people walking out of those freezing hills in the deadness of a January night, something had to be done.

A couple of those lawmen never left the outskirts of Shady Hollow once it came to light what they’d been doing. They were running off business, Ma said, and they were giving Shady the crookedest name of the very crookedest kind.

Those deputy sheriffs never even made it into the hard but forgiving dirt of Polly Hill, neither, once they ignored threats and turned down bribes and were sentenced according to a final judgment by the Shady elders. They ended up bobbing down the river with their bellies bloated and their badges pinned to their foreheads for all to take warning of downstream.

I guess Shady is where I grew up in about every way a young man could and I saw almost every kind of good and bad there is to see. Almost.

Shady Hollow is all gone now, all of it, except for the dead still buried there. I still ain’t sure if the kneelers finally got their prayers tended to or it finally outlived its times. Maybe it just came down to plain bad luck that outsiders might call prosperity.

Over the years many more than a few died trying to find and get to Shady, wandering up on the wrong liquor still or copperhead at the wrong time, or just getting lost in the wilderness. If for no other reason, I still figure there must have been something decent—and maybe even special about the place—if so many folks died trying to find it. It was something in its day, and I’m sure in the last moment before it took its final breath, the diehards of the holdouts threw the party of all parties.

I missed that fine celebration that I can only imagine. But contrary to what some people still claim, it wasn’t because I had six feet of clay piled over top me on Polly Hill.

Most days I’m still pretty sure I ain’t dead yet. Maybe a little bit dead, maybe a whole lot more than a little bit.

But I’m still here.

I had to leave Shady in a great big hurry on September 28, 1959. September 28 fell on a cool early fall Sunday, and I was seventeen years old. And even though I’ve survived so many things since, I still think about it. Especially when dark falls and all gets still and quiet but the visions and ghosts of once was, and once that was never to be, who come back again and again to pay me a visit.

Almost half a century has passed since the shooting. But the sounds and sights of Ma’s yelling and crying, and Amanda Lynn’s screaming, and every single thing that happened on that Sunday afternoon is carved as deep into me as it is into homemade river-rock tombstones overlooking what once was a place called Shady Hollow.

Chapter 1

Harrisburg Federal Penitentiary June 16, 1980

“You’re not out yet, Henry. Well, keep that in mind, yep,” he said.

The guard behind my left shoulder—the head goon who ducked through doorways and always walked behind prisoners with my kind of history—tapped me on the right shoulder with his stick. Tapped probably ain’t the right word. He hit me with it not hard enough to leave a mark a day later but hard enough to where I’d feel it a week later, whatever that word is. I was used to him walking behind me, and had come to know his stick in a personal kind of way. My head had put a few dents in it.

Officer Dollinger always ended everything he said with the word “yep,” and he was letting his stick tell me that I’d been mouthing off too much to a new guard walking in front of me.

Anyway, the head of the beef squad behind me had never called me Henry before. It seemed the whole bunch of them would come up with new words to call us every few years, same as we’d come up with new words to call them. Lately the guards called all of us convicts either Con or Vic.

Don’t see that in movies, prisoners being called Vic. Don’t see a lot of things in prison movies, at least the ones they’d shown us in prison, that actually make being locked up look and sound and smell like what it is, which is similar but different in an uglier, more crowded, louder, smellier way.

But mostly the guards just called me and the rest of us “you.” After I’d learned to write, I’d signed so many of their forms over the years with that name.

You.

But in D Block, Pod Number Four-B of the Number Nine Building known as the Special Housing Unit of Harrisburg Federal Penitentiary, the few pards I trusted with some things but not all, and had become friends with as much as you can in a place like a prison, called me “Shady.”

At some point in some lockup or lockdown, I was feeling dangerous lower than is good for a man to feel, and I decided I might need something to remember who I used to be before I had to live behind tall walls and wire, even if I couldn’t feel that way no more. On my last day in prison, both of my arms were covered in fading blue ink, pictures and words. Those prison tattoos read like a book of my youth, and across my back and shoulders in big letters was the word “Shady.” It was the first thing I’d ever had scratched into me. Nobody knew what Shady meant because I never told anybody about my past or what little I knew of it, but it came to be what I was called by the other inmates.

So anyway, given a kind warning by stick standards, I decided to not say anything more to the new jug-head guard in front of me. I just kept shuffling slow and steady, wearing irons on my ankles that I’d gotten used to so much that I’d grown permanent calluses from them. I kept shuffling slow and kept my bearing about me as I tried to ignore the irksome clanking of the chains at midstep, because it wouldn’t do me well to raise hell about any of it.

I’d already been through eight hours of a hurry up and wait drill, first in my empty cell with a rolled-up bed, and then sitting outside the warden’s office watching the guards keeping an eye on me over top issues of Life, Field & Stream and National Geographic magazines.

An old trustee with heavy glasses on and small shoulders who seemed to have been there before time began and a man who I’d always gotten along with somewhat tolerable came in to say at long last that the head man of the Harrisburg Federal Penitentiary was busy attending to a bunch of local politicians touring the place.

All of the guards laid down their aged magazines, bored, like they’d probably done a thousand other times, and then they grabbed me up and escorted me to another waiting room. After I watched them sip on cold bottles of pop for another hour, I finally had my farewell talk with the assistant warden.

The tall shiny wooden sign sitting on top of his desk yelled that his name was Theodore Donald O’Neil, the Third. And he was young, a good bit younger than me, and I wasn’t that old. He seemed proud of himself sitting behind his long name and polished oak desk in a way a young man is until he’s really tested and finds out what’s really inside of him.

But like this old Chinese lady had come in to teach us once, I kept focusing on my breathing. I took in air slow like it was the gift of life and let my lungs fill up with the gift before letting it out, just as I’d done over and over from years of trying to let out what was about to make me explode, or eat my insides away to nothing.

The assistant warden told me to sit.

I sat.

He looked so serious, and then he grinned.

He leaned back carrying that grin and stared as hard as he could for what seemed a decent long time until his eyes started to get watery.

“If it were up to me, you wouldn’t be leaving. I’ve scanned your file and sitting here looking at you, I know you’re still a threat to society. It’s written all over your face.”

I kept staring at him because my eyes had dried up years ago when something deep down in me turned the water off, and I could now stare at anybody until I just got so bored with it that I’d decide to stare at something else. It was written all over Mr. O’Neil that he wasn’t quite yet the hard man he’d need to be in this new job, as his eyes left mine and he began talking again and fiddling with a pencil that had teeth marks on it.

“Besides not making parole several times for various violations, you’ve been involved in several serious altercations. You even managed to kill an inmate here.”

“I’m sure it’s in the file what I did and why,” I said.

“Actually, the file only has your version of what happened, being the other man is dead.”

“I had to defend myself if I wanted to keep living is the short of it.”

“Yes…you never did say why the man tried to kill you, as was your story.”

“Don’t know.”

He looked over the papers at me. “Well, we can’t ask his version of what happened, can we?”

“You could dig him up but I suspect he wouldn’t say a whole lot,” I said.

He kept looking at me for a good spell, then at the head guard before he eyed his watch. Then he turned his attention square back at me.

“The warden doesn’t have any other recourse than to let you go. I’d like to believe that you’ll begin leading a decent life, but your nature toward violence will lead you right back into incarceration, if you don’t get killed first, of course. But you’re a hard man to kill, aren’t you, Henry Cole?”

“This damned place hasn’t killed me yet.”

“This institution didn’t try to kill you, it tried to rehabilitate you. And we failed in that task. The taxpayer’s money has been wasted in that regard. You are living, breathing proof that some men cannot change their behavior, and therefore they should be restrained and kept from society that they will naturally prey on and do harm to. It’s my opinion that you should be kept here for as long as you have the capacity to continue to be a threat to others, which would be until you are either a feeble old man or until you die. But as you know, even though you still have evil in your eyes as you sit there staring at me, I lack the authority to keep you here and throw away the key, as they say. I did want you to know my feelings on the matter, however.”

I couldn’t hardly stand to be quiet anymore with that young man with not a scar on him judging me the way he was doing, but I kept trying to sit on my temper best I could. It was starting to catch my ass on fire.

“What’re your plans?”

“Don’t have any,” I lied.

“None?”

“Not a single one,” I lied again.

“What do people like you think about in here for…what was it…eight years?” he asked.

“I’ve been here a lot longer than eight years.”

“Didn’t you ever think about what you would do when you were released?”

“What do you think about in here when you’re locked up behind the same rusty bars as I am, day after day?” I asked back.

The assistant warden tried to grow another grin but it slid away.

“I can leave here whenever I want. You can’t. But to answer your question, I think about how to make sure predators like you stay here where you belong,” he said. “It’s very, very satisfying.”

He looked like he meant what he said, and I respected him more than I did when I’d first laid eyes on him, but still not much. He went back to scanning and flipping page after page of I guess what amounted to my life in prison, which amounted to all of my adult life. He stopped to read one section with a lot of care.

“You’ve been housed in protective custody most of your time here. Why?”

I didn’t say anything as he kept reading. He finally looked up.

“Why the attacks?”

“If it ain’t in there, I don’t know,” I said. “I was actually hoping you might.”

“You don’t know why inmates on two other occasions tried to kill you?”

“I didn’t even know them.”