Полная версия:

Natural History in the Highlands and Islands

Collins New Naturalist Library

6

Natural History in the Highlands and Islands

F. Fraser Darling

D.Sc. F.R.S.E.

With 46 Colour Photographs By F. Fraser Darling, John Markham and Others, 55 Black-and-White Photographs and 24 Maps and Diagrams

TO THE MEMORY OF

WILLIAM ORR, F.R.C.V.S.

† Singapore, December 1945

KENNETH McDOUGALL, M.Sc., M.R.C.V.S.

† Normandy, August 1944

WHO KNEW AND LOVED THE HIGHLANDS AND ISLANDS

AND THE WILD LIFE THEREIN

Editors:

JAMES FISHER M.A.

JOHN GILMOUR M.A.

JULIAN S. HUXLEY M.A. D.Sc. F.R.S.

L. DUDLEY STAMP B.A. D.Sc.

PHOTOGRAPHIC EDITOR:

ERIC HOSKING F.R.P.S.

The aim of this series is to interest the general reader in the wild life of Britain by recapturing the inquiring spirit of the old naturalist. The Editors believe that the natural pride of the British public in the native fauna and flora, to which must be added concern for their conservation, is best fostered by maintaining a high standard of accuracy combined with clarity of exposition in presenting the results of modern scientific research. The plants and animals are described in relation to their homes and habitats and are portrayed in the full beauty of their natural colours, by the latest methods of colour photography and reproduction.

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Editors

Editor’s preface

Author’s preface

CHAPTER 1 GEOLOGY AND CLIMATE

CHAPTER 2 RELIEF AND SCENERY

CHAPTER 3 RELIEF AND SCENERY (continued)

CHAPTER 4 THE HUMAN FACTOR AND REMARKABLE CHANGES IN POPULATIONS OF ANIMALS

CHAPTER 5 THE DEER FOREST GROUSE MOOR AND SHEEP FARM

CHAPTER 6 THE LIFE HISTORY OF THE RED DEER

CHAPTER 7 THE PINE FOREST, BIRCH WOOD AND OAK WOOD

CHAPTER 8 THE SUMMITS OF THE HILLS

CHAPTER 9 THE SHORE, THE SEA LOCH AND THE SHALLOW SEAS

CHAPTER 10 THE SUB-OCEANIC ISLAND

CHAPTER 11 THE LIFE HISTORY OF THE ATLANTIC GREY SEAL

CHAPTER 12 FRESH WATERS: LOCHS AND RIVER SYSTEMS

Conclusion

Bibliography

Maps showing the distribution of certain animals in the highlands

Index

Black and White Plates

Colour Plates

Copyright

About the Publisher

EDITORS’ PREFACE

FOR MANY years Dr. F. Fraser Darling has found his field of work in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. One of his pioneer researches was into the social behaviour of a herd of red deer, in an area of Wester Ross dominated by the massif of An Teallach. In 1936 he began the first of two seasons’ work on Priest Island of the Summer Isles, studying the social structure of gull colonies and of small flocks of grey lag geese and other gregarious birds. It was from this work that Dr. Darling was led to enunciate his theory connecting the size of a social group of gregarious animals, with its breeding-time, and breeding-success. Statistical analysis and further observation by other workers have confirmed this theory and shown it to be of wide biological importance. Darling then made protracted autumn and winter visits to Lunga of the Treshnish Isles, and to North Rona, in order to study a further type of animal sociality, that of the Atlantic grey seal, an animal of whose life history we knew surprisingly little. He also worked his small farm on Tanera in the Summer Isles in such fashion as to show that it was possible and reasonable to raise considerably the stock-carrying capacity of the West Highlands and to grow a large amount of human food under crofting conditions.

Fraser Darling is a born naturalist, was brought up to farming, and became a scientist as thoroughly and quickly as academic discipline permitted. His first researches (at the Institute of Animal Genetics, Edinburgh University) were on the Scottish Mountain Blackface breed of sheep. He combines the qualities of a trained biologist and practical farmer with those of a sensitive field observer. As a humanist he is considering the Highland problem with none of the peculiar obsessions with which it has so often been approached: some Highland countrymen believe only in sport, or stalking, or sheep: others believe that no problem is more important than crofting, or water power, or the tourist industry, or the collecting of rare alpine plants. Fraser Darling’s sympathies are with all the interesting problems of living things in the Highlands, not least with the human species which—in this wild part of Britain where man is in such close contact with the natural physical environment—must be regarded in relation to the others. It is in this spirit that he is interpreting his present work as Director of the West Highland Survey.

In this book, which is the first effort, so far as we are aware, to give a picture of Highland natural history as a whole, Dr. Darling has, naturally, expanded on those subjects with which he is most familiar—the life histories of seals, deer and sea-birds, and the ecology of grazing and regeneration of forest growth. Nevertheless, he has a general view, derived from a wide and mature experience, tempered with homely wisdom, and illuminated by his genuine love for the Highlands. There is, in this book, no aura of bogus romance; there are no purple passages or sporting reminiscences: instead, he has given us something of the real essence of Scotland’s land and sea.

THE EDITORS

Every care has been taken by the Editors to ensure the scientific accuracy of factual statements in these volumes, but the sole responsibility for the interpretation of facts rests with the Authors

AUTHOR’S PREFACE

A MAN does not write a book like this one without a good deal of help. First, there is that host of observers and seekers after knowledge whose works have been scanned for their contribution to this attempted synthesis. Then there is the good criticism given by the Editors, James Fisher in particular, for his friendship has been sorely tried. Charles Elton was good enough to spend part of his first holiday in seven years reading the draft, and his suggestions have been invaluable. Averil Morley has helped me throughout in gathering data and as a constant kindly critic. I am grateful to them all, but would not like to unload on to them any of the responsibility for this book. After all, I have not always taken their advice and must stand or fall alone in what seems to me something of a tight-rope act. This work is not a handbook of natural history; that is why I have refused to call it The Natural History of the Highlands and Islands; that would have been too presumptuous a title. Whole orders of animals and plants escape any mention, partly for want of space but mainly, perhaps, because one man is not omniscient. The aim has been to tell a plain tale of a remarkable region and of some of the causes, interactions and consequences which confront the inquiring mind. One thing I would say: I know more now about natural history in the Highlands and Islands than when I began this book three years ago, and writing it has set me thinking. I want to get into the field again and look into new problems that have occurred to me. If the book has the same effect on anybody else, it will have served some good purpose.

F. D.

Strontian,

North Argyll.

CHAPTER 1

GEOLOGY AND CLIMATE

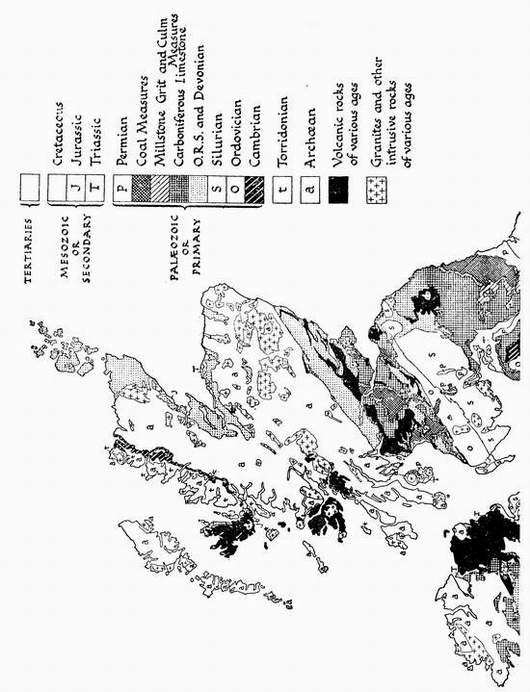

IT MAY be truly said of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland that the geology of the country makes the scenery. The geology cannot be ignored in describing the area, as the subject might be if the rocks were overlaid with a great thickness of soil deposited by alluvial drift. Here in the Highlands there is often no soil at all, the bare rocks starkly showing to sun and tempest; or again, a thin layer of acid peat may be the only covering. Such true soils as exist on the hillsides and in the straths are usually of fairly local origin, reflecting the qualities of the rocks near at hand.

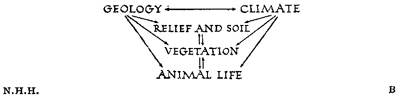

Geology, then, linked with climate, determines very largely the nature of the initial vegetation of the Highlands. Man himself determines the secondary vegetation to some extent through his management of animals and of fire, but there are decided limits to what he can do in the face of the geology. Vegetation in its turn, and again governed by climate, has a remarkable effect on the animal life of the region, both in variety and distribution. Geology, through the relief of the land to which it gives rise, also has a definite effect on climate—for example, the presence of mountains results in the condensation of the moisture of the air, hence the characteristic heavy rainfall in their vicinity. The vegetation influences slightly the immediate climate of a region, and the two together may have their effect on the superficial geology, as in woodlands preventing erosion and gullying of hillsides.

We should remember the constant interplay of these dynamic forces as well as life itself in studying the natural history of the Highlands and Islands. It is a noble drama of weather and mountain and sea and plant and animal, the dramatis personae of which may be given this diagrammatic form:

From almost every point of view of natural history, the Highland region of Scotland is demarcated by the sharp geological line known as The Highland Border Fault which runs north-east, south-west across Scotland from the mouth of the Clyde to Stonehaven. Although a good deal of Scotland’s best agricultural land lies along the east coast north of this line, the great mass of the country to the north-west of the Fault (also known in history as the Highland line) is mountainous. The word mountainous does not, however, allow us properly to speak of mountains in Scotland. It is rather an inverted boast of the Scot, secure in his country’s superiority of wild terrain, to inform the visitor that there are reputedly mountains in England and Wales and in Ireland, but in Scotland they are called hills.

The Highlands, also, are not necessarily high ground. The highest point of the Hebridean island of Benbecula is only 420 feet, but Benbecula is unquestionably as Highland in its natural history as in its human cultural relationships.

There is another major geological feature which plays a large part in the topography of the area, in the shape of the Great Glen of Scotland, a second big fault forming Glen Albyn (the English have an annoying habit of calling it the Caledonian Canal!). This great dividing line between the Northern and North-West Highlands on the one hand and the Central and South-West Highlands on the other is marked not only by the Great Glen itself, but by the chain of long freshwater lochs it contains, the most famous of which is Loch Ness, 21 3/4 miles long and of great depth. The loch drains north-eastwards to the short Ness River and the Moray Firth at Inverness. The very low watershed which crosses the Great Glen, in so far as the flow northeast or south-west is concerned, is above the head of Loch Oich and is no more than 115 feet above sea level. The next loch south-westwards is Loch Lochy, and the Lochy River which flows from it runs into the salt water of Loch Linnhe, which ultimately fans out after the Corran Narrows and becomes the Firth of Lorne which is such a distinctive feature of the western coastline. At the south-westward end of the Great Glen and at the head of Loch Linnhe stands the sentinel-like massif of Ben Nevis, the highest hill in Scotland, 4,406 feet high. The summit is only four miles from sea level as the crow flies, so the full sense of height of this mass can be appreciated by the traveller coming eastwards down Loch Eil. Ben Nevis is formed by a granite intrusion between the two great areas of the Moine and Dalriadan schists. It is a wide-topped hill of no particular beauty of shape, but its north corrie is undoubtedly impressive, for it contains the highest sheer cliff face in Britain of about 1,500 feet (Plate I) as well as one of the very few semi-permanent snow patches in Britain. This patch of snow is untouched by the sun’s rays.

The actual summit of Ben Nevis is not of the granite rock of which the main mass of the hill is composed. The summit is the top of a gigantic cylinder of tertiary basalt. Presumably this volcano originally spread the basalt over the whole of the hill, but all except the protected summit has been eroded away.

It is worth noting that the two highest mountainous groups in Scotland are formed of granite—Ben Nevis, and the Cairngorm region, 4,296 feet, east of the Spey; and east again, there is Lochnagar, on the eastern side of the Highland area, also granite and reaching 3,760 feet. The Cairngorms are of much greater extent than the Ben Nevis massif and, partly because of their considerable alpine plateaux at about the 4,000-foot contour, have a special place in Highland natural history. Topographically, the Cairngorms viewed from afar may seem as uninteresting as Ben Nevis, but the physical beauty of these hills is for intimate observation in the magnificent corries and on the high plateaux. It is possible to walk a pony on to these high ridges and plateaux without any trouble, the ground being good all the way.

There are two more striking geological phenomena which will be less obvious to the casual observer than those of the Highland Boundary Fault and the Great Glen. First, that definite line of tectonic tumult known as the Moine Overthrust which reaches from the south-west corner of Skye north-north-eastwards to the eastern shore of Loch Eriboll on the north coast. Here the older rocks of the Moine schists are thrust westwards over younger rocks along a hundred-mile line. Through the whole length, like a sandwich filling between archaean gneiss with the overlying Torridonian sandstone on the west side, and the Moine schists on the east, are beds of Cambrian age including an extremely hard and shiny metamorphosed quartzite which makes a barren strip of country. This rock is so hard and shiny that even the peat finds it difficult to keep a hold on slopes of any considerable inclination. There are many patches of acres of bare rock (Plate 3a) to be found on the passage of the quartzite from Eriboll to Skye, and it may be best described in the climber’s graphic phrase of “boiler-plating.”

Here and there along the line of this uninteresting sandwich filling there appears a geological titbit in the shape of an outcrop of limestone such as the famous Durness limestone of Cambrian age. The effect of this is to enliven the natural history and change the scenery of this vast geological sandwich. Instead of bareness and blackness of peat we get greenness and soil. It is this limestone which makes the Assynt district a place which no naturalist should ignore from the geological, entomological, conchological or botanical points of view. The effect is, perhaps, still more marked around Durness. Even the bird life has its particular interest in this area and so has the world of loch and river. A little farther south than Assynt, in a black area of bog to the east of Suilven and Canisp, there rises an island of limestone a few hundred acres in extent. The climber on these hills in spring or autumn will experience pleasure and something of a shock to see the townships of Elphin and Cnockan on their geological emerald. If he goes down to these thriving villages he will notice that the sheep are larger, the cattle better-looking, and there will be Highland pony mares and foals such as he will see nowhere else so commonly till he reaches the machairs of South Uist. The roadsides are like the verges of an English lane. All this is part of the paradox of the Highlands and of Highland life. They are full of surprises and facts which do not seem to fit in. No sooner does the theorizing type of mind construct a hypothesis which looks neat than some disconcerting fact will create paradox.

So much for the Moine Thrust and its consequences; the second striking geological phenomenon is the mixture in the West Highlands of old rocks and new volcanic ones. From Cape Wrath to Applecross the West Coast is a wild jumble of the ancient Hebridean gneiss and that very old and barren sandstone known as Torridonian. These two formations make for scenery which is exceptionally wild in quite different ways. Then at the foot of Loch Linnhe is the Isle of Mull and, to the north of it, some similar tertiary volcanic rocks in Morvern and Ardnamurchan. Such volcanic rock is a dull grey in colour and amorphous in texture, except where there occur amygdaloid pockets of crystals of much beauty, but it makes some distinctive scenery. These tertiary rocks as we see them in Mull are the remains of immense beds of lava, possibly 50 million years of age as against the 1,500 million years or so of the gneiss farther north. The lava erodes into terrace-like formations which correspond to the actual flows, and on which terraces the soil is found to be brown and rich—a real soil without peat—and the grass grows thick in summer. The country of the tertiary terraces is cattle country and turns up again in the western part of Skye. Sometimes the terraced denudation gives way to a natural castellated architecture such as the Castle Rock of the Treshnish Isles (Plate Va), and further still to towers and spires like the Quirang and the Old Man of Storr in Skye (Plate II). This latter rock is like a natural Tower of Pisa and visible from many miles away. Sometimes, again, the tertiary basalt has solidified in a peculiar way to make those giant hexagonal columns much visited at Staffa, the small island between Iona and the Treshnish Isles. Such columns may also be found elsewhere, as in Mull, Canna and Oidhsgeir, on a much smaller scale, but probably the most impressive examples in Scotland are those of the northern face of Garbh Eilean of the Shiant Isles. Though the steamer from Kyle of Lochalsh to Stornoway passes within four miles of the Shiants, these islands are rarely visited, and the tremendous columnar architecture remains almost unknown. The Shiants are the northern outposts of Scotland’s youngest rocks; only four miles away to the west is the east coast of the Hebrides, composed of her oldest rock, the archaean gneiss. Geology is a hard subject to learn, but it helps one to understand scenery, and with a little knowledge it gives great sense of wonderment at the immensity of the movements of the earth’s crust.

The Moine Thrust has been mentioned as one of the major geological features of the Highlands. The Moine schists which occur to the east of the Thrust are the most extensive group of rocks found in the Highlands as a whole. They are sometimes called the Undifferentiated Eastern Schist, and words such as gneissose and schistose crop up in a detailed geological description; but whatever the names, the group of rocks reaches in a broad, roughly parallel-sided band, fifty miles wide, from the north coast of Scotland to the foot of the Great Glen where it comes up short against the tertiary basalt of Mull and western Morven. South of the Great Glen, similar schists and gneisses, the Dalriadan, underlie a large part of the Central Highlands and reach far into Aberdeenshire. Many of the high tops of the Highlands are on this formation—Ben Lawers 3,984 feet, Craig Meagaidh 3,700, Mam Soul 3,862 and Carn Eige 3,877 feet. The schists form a great plateau on the western side of the Spey opposite the Cairngorms. This schist plateau has the Gaelic name of Monaliadh —the grey mountains—and the Cairngorms across the valley are called the Monaruadh—the red mountains. The grey is most obvious when it comes up against either the granite as on the east side of the Highlands, or against the reddish-purple Torridonian, as on the west. Though schists and gneisses are intimately associated and both very ancient, the schists break down more easily, and as they contain a fair quantity of alumina they often make good soil, and produce a different vegetational complex from the adjoining Torridonian, for example. The presence of overmuch peat, of course, may entirely cut out the influence of the slowly-disintegrating rock.

FIG 1.—Geology of the Highlands The exposures of Tertiary and Cretaceous are not large enough to show on this scale

An igneous rock known as gabbro is of infrequent occurrence in the Highlands, but its appearances and the consequences of glacial action on the gabbro constitute some of the most spectacular scenery not only in the Highlands but in the whole world. The more important masses of gabbro are closely associated with the tertiary lava and are in fact intrusive masses of molten rock which solidified underground but have since been exposed by denudation. The small example of gabbro scenery in the shape of Ardnamurchan Point, the most westerly point of the mainland of Great Britain, is wild, but not high enough to be considered grand, but this rock in Skye is the stuff of the Cuillin hills (Plate IIIa) which rise to 3,309 feet. Gabbro is hard and knobbly, which makes it safe for the experienced climber, and by the coincidence of the Cuillin range being the centre of an ice cap in glacial times, the glaciers working outwards to the perimeter have carved the great corries and left the sharp ridges in which we delight to-day. With the retreat of the glaciers the shape of the moraines becomes obvious, and subsequent weathering of the hills has produced some great scree slopes.

South-west of Skye there is another fairly large island of nearly 30,000 acres, called Rum. Its highest hills do not go beyond 2,600 feet, but in beauty of line they are not less than the Cuillins; and when we come to examine their geology, we find that nearly a third of the island, including these fine hills, is composed of gabbro.

Another mass of gabbro and allied rocks occurs over a hundred miles farther west to form the group of islands known as St. Kilda. They are unique in British scenery and in British natural history. Here, the Atlantic has not allowed the accumulation of the fragments which result from weathering and make the scree slopes seen in the Cuillins. Instead, the gabbro stands up out of the sea in naked pinnacles. The highest point of the largest island, Hirta, is 1,396.8 feet above sea level, from just below which is the highest sheer sea-cliff in Britain. (This is disputed by those who say the Kame of Foula, 1,220 feet, is the highest.) Even so, the island being three miles or so across, the height of this cliff is not so striking as the smaller island of Boreray on the north side of the group, which being roughly triangular and less than a mile across rises to 1,245 feet. Stac Lee and Stac an Armin are mere rocks in the sea, a furlong or less across at their foot, but they rise to 544 and 627 feet and make a difficult climb for a good man (Plates XXIb and XXIX). It is on these stacks of gabbro in the western ocean that the largest gannet colonies in the world are found.

Finally, the 70-foot stack of Rockall (Plate XXII), 184 miles west of St. Kilda, is of a rock allied to gabbro though more acid in composition. The natural history of that rock, in so far as it is known, would not fill a volume. No birds breed on it regularly though guillemots do from time to time. Lichens there may be but no other vegetation. Gannets and other sea birds are often found resting there in summer. Near it is Leonidas or Hazelwood Rock, usually awash. Farther away Helen’s reef, about a mile long comes to the surface only at spring tides in one place, so the geological nature of this submerged land is unknown to us. The naturalist, of all men, cannot resist the temptation sometimes to dream of what Rockall would have been had it thrust itself just another hundred feet through the waves and been able to withstand the wave action which has reduced it to its present proportions. We should have had a long low island with a hump and a few smaller eminences. What sort of a place would it have been botanically? What haven would it have made for nesting birds from the sea, and would the Atlantic seal have been an altogether more numerous species than it is, by having a North Atlantic sanctuary which would usually have been unapproachable during the autumn breeding season? James Fisher tells me that on an exceptionally calm day the Leonidas Rock may dry out and would provide the only possible hauling-out place for the seal; but in fact, the Atlantic seal has been seen only once in the vicinity.