Полная версия:

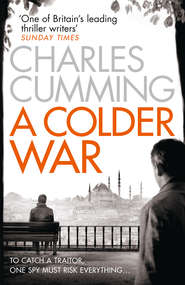

A Colder War

CHARLES CUMMING

A Colder War

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Copyright © Charles Cumming 2014

Cover design layout © HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Cover photographs © Josephine Pugh/Arcangel Images (cityscape); Henry Steadman (foreground and figure, right); Superstock (bench, seated man); Shutterstock.com (all other images).

Charles Cumming asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Extract from The Double-Cross System by Sir John Masterman. Published by Vintage. Reprinted by permission from The Random House Group Limited.

Extract taken from ‘Postscript’ taken from The Spirit Level by Seamus Heaney © Estate of Seamus Heaney and reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007467501

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2014 ISBN: 9780007467495

Version: 2018-06-04

Praise for A Colder War:

‘The spy thriller has been on the ascendant in the past few years, breeding a bunch of talented writers, Cumming among the very best’ The Times

‘An espionage maestro … The levels of psychological insight are married to genuine narrative acumen – but anyone who has read his earlier books will expect no less’ Independent

‘A cleverly plotted spy tale’ Sun

‘Cumming’s prose is always lean and effective, but I was struck by the many times he injected phrases and descriptions so nice that I stopped to savour them’ Washington Post

‘A Colder War is more than an excellent thriller: it is also a novel that forces us to look behind the headlines and question some of our own comfortable assumptions’ Spectator

Dedication

For Christian Spurrier

‘Certain persons … have a natural predilection to live in that curious world of espionage and deceit, and attach themselves with equal facility to one side or the other, so long as their craving for adventure of a rather macabre type is satisfied.’

John Masterman, The Double-Cross System

‘… You are neither here nor there,

A hurry through which known and strange things pass

As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways

And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.’

Seamus Heaney, ‘Postscript’

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for A Colder War

Dedication

Epigraph

Turkey

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

London: Three Weeks Later

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Keep Reading …

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By Charles Cumming

About the Publisher

1

The American stepped away from the open window, passed Wallinger the binoculars and said: ‘I’m going for cigarettes.’

‘Take your time,’ Wallinger replied.

It was just before six o’clock on a quiet, dusty evening in March, no more than an hour until nightfall. Wallinger trained the binoculars on the mountains and brought the abandoned palace at İshak Paşa into focus. Squeezing the glasses together with a tiny adjustment of his hands, he found the mountain road and traced it west to the outskirts of Doğubayazit. The road was deserted. The last of the tourist taxis had returned to town. There were no tanks patrolling the plain, no dolmus bearing passengers back from the mountains.

Wallinger heard the door clunk shut behind him and looked back into the room. Landau had left his sunglasses on the furthest of the three beds. Wallinger crossed to the chest of drawers and checked the screen on his BlackBerry. Still no word from Istanbul; still no word from London. Where the hell was HITCHCOCK? The Mercedes was supposed to have crossed into Turkey no later than two o’clock; the three of them should have been in Van by now. Wallinger went back to the window and squinted over the telegraph poles, the pylons and the crumbling apartment blocks of Doğubayazit. High above the mountains, an aeroplane was moving west to east in a cloudless sky, a silent white star skimming towards Iran.

Wallinger checked his watch. Five minutes past six. Landau had pushed the wooden table and the chair in front of the window; the last of his cigarettes was snuffed out in a scarred Efes Pilsen ashtray now bulging with yellowed filters. Wallinger tipped the contents out of the window and hoped that Landau would bring back some food. He was hungry and tired of waiting.

The BlackBerry rumbled on top of the chest of drawers; Wallinger’s only means of contact with the outside world. He read the message.

Vertigo is on at 1750. Get three tickets

It was the news he had been waiting for. HITCHCOCK and the courier had made it through the border at Gürbulak, on the Turkish side, at ten to six. If everything went according to plan, within half an hour Wallinger would have sight of the vehicle on the mountain road. From the chest of drawers he pulled out the British passport, sent by diplomatic bag to Ankara a week earlier. It would get HITCHCOCK through the military checkpoints on the road to Van; it would get him on to a plane to Ankara.

Wallinger sat on the middle of the three beds. The mattress was so soft it felt as though the frame was giving way beneath him. He had to steady himself by sitting further back on the bed and was taken suddenly by a memory of Cecilia, his mind carried forward to the prospect of a few precious days in her company. He planned to fly the Cessna to Greece on Wednesday, to attend the Directorate meeting in Athens, then to cross over to Chios in time to meet Cecilia for supper on Thursday evening.

The tickle of a key in the door. Landau came back into the room with two packets of Prestige Filters and a plate of pide.

‘Got us something to eat,’ he said. ‘Anything new?’

The pide was giving off a tart smell of warm curdled cheese. Wallinger took the chipped white plate and rested it on the bed.

‘They made it through Gürbulak just before six.’

‘No trouble?’ It didn’t sound as though Landau cared much about the answer. Wallinger took a bite of the soft, warm dough. ‘Love this stuff,’ the American said, doing the same. ‘Kinda like a boat of pizza, you know?’

‘Yes,’ said Wallinger.

He didn’t like Landau. He didn’t trust the operation. He no longer trusted the Cousins. He wondered if Amelia had been at the other end of the text, worrying about Shakhouri. The perils of a joint operation. Wallinger was a purist and, when it came to inter-agency cooperation, wished that they could all just keep themselves to themselves.

‘How long do you think we’ll have to wait?’ Landau said. He was chewing noisily.

‘As long as it takes.’

The American sniffed, broke the seal on one of the packets of cigarettes. There was a beat of silence between them.

‘You think they’ll stick to the plan or come down on the 100?’

‘Who knows?’

Wallinger stood at the window again, sighted the mountain through the binoculars. Nothing. Just a tank crawling across the plain: making a statement to the PKK, making a statement to Iran. Wallinger had the Mercedes’ numberplate committed to memory. Shakhouri had a wife, a daughter, a mother sitting in an SIS-funded flat in Cricklewood. They had been waiting for days. They would want to know that their man was safe. As soon as Wallinger saw the vehicle, he would message London with the news.

‘It’s like clicking “refresh” over and over.’

Wallinger turned and frowned. He hadn’t understood Landau’s meaning. The American saw his confusion and grinned through his thick brown beard. ‘You know, all this waiting around. Like on a computer. When you’re waiting for news, for updates. You click “refresh” on the browser?’

‘Ah, right.’ Of all people, at that moment Paul Wallinger thought of Tom Kell’s cherished maxim: ‘Spying is waiting.’

He turned back to the window.

Perhaps HITCHCOCK was already in Doğubayazit. The D100 was thick with trucks and cars at all times of the day and night. Maybe they’d ignored the plan to use the mountain road and come on that. There was still a dusting of snow on the peaks; there had been a landslide only two weeks earlier. American satellites had shown that the pass through Besler was clear, but Wallinger had come to doubt everything they told him. He had even come to doubt the messages from London. How could Amelia know, with any certainty, who was in the car? How could she trust that HITCHCOCK had made it out of Tehran? The exfil was being run by the Cousins.

‘Smoke?’ Landau said.

‘No thanks.’

‘Your people say anything else?’

‘Nothing.’

The American reached into his pocket and pulled out a cell phone. He appeared to read a message, but kept the contents to himself. Dishonour among spies. HITCHCOCK was an SIS Joe, but the courier, the exfil, the plan to pick Shakhouri up in Doğubayazit and fly him out of Van, that was all Langley. Wallinger would happily have run the risk of putting him on a plane from Imam Khomeini to Paris and lived with the consequences. He heard the snap of the American’s lighter and caught a backdraught of tobacco smoke, then turned to the mountains once again.

The tank had now parked at the side of the mountain road, shuffling from side to side, doing the Tiananmen twist. The gun turret swivelled north-east so that the barrel was pointing in the direction of Mount Ararat. Right on cue, Landau said: ‘Maybe they found Noah’s Ark up there,’ but Wallinger wasn’t in the mood for jokes.

Clicking refresh on a browser.

Then, at last, he saw it. A tiny bottle-green dot, barely visible against the parched brown landscape, moving towards the tank. The vehicle was so small it was hard to follow through the lens of the binoculars. Wallinger blinked, cleared his vision, looked again.

‘They’re here.’

Landau came to the window. ‘Where?’

Wallinger passed him the binoculars. ‘You see the tank?’

‘Yup.’

‘Follow the road up …’

‘… OK. Yeah. I see them.’

Landau put down the binoculars and reached for the video camera. He flipped off the lens cap and began filming the Mercedes through the window. Within a minute, the vehicle was close enough to be picked out with the naked eye. Wallinger could see the car speeding along the plain, heading towards the tank. There was half a kilometre between them. Three hundred metres. Two.

Wallinger saw that the tank barrel was still pointing away from the road, up towards Ararat. What happened next could not be explained. As the Mercedes drove past the tank, there appeared to be an explosion in the rear of the vehicle that lifted up the back axle and propelled the car forward in a skid with no sound. The Mercedes quickly became wreathed in black smoke and then rolled violently from the road as flames burst from the engine. There was a second explosion, then a larger ball of flame. Landau swore very quietly. Wallinger stared in disbelief.

‘What the hell happened?’ the American said, lowering the camera.

Wallinger turned from the window.

‘You tell me,’ he replied.

2

Ebru Eldem could not remember the last time she had taken the day off. ‘A journalist,’ her father had once told her, ‘is always working’. And he was right. Life was a permanent story. Ebru was always sniffing out an angle, always felt that she was on the brink of missing out on a byline. When she spoke to the cobbler who repaired the heels of her shoes in Arnavutköy, he was a story about dying small businesses in Istanbul. When she chatted to the good-looking stallholder from Konya who sold fruit in her local market, he was an article about agriculture and economic migration within Greater Anatolia. Every number in her phone book – and Ebru reckoned she had better contacts than any other journalist of her age and experience in Istanbul – was a story waiting to open up. All she needed was the energy and the tenacity to unearth it.

For once, however, Ebru had set aside her restlessness and ambition and, in a pained effort to relax, if only for a single day, turned off her mobile phone and set her work to one side. That was quite a sacrifice! From eight o’clock in the morning – the lie-in, too, was a luxury – to nine o’clock at night, Ebru avoided all emails and Facebook messages and lived the life of a single woman of twenty-nine with no ties to work and no responsibilities other than to her own relaxation and happiness. Granted, she had spent most of the morning doing laundry and cleaning up the chaos of her apartment, but thereafter she had enjoyed a delicious lunch with her friend Banu at a restaurant in Beşiktaş, shopped for a new dress on Istiklal, bought and read ninety pages of the new Elif Şafak novel in her favourite coffee house in Cihangir, then met Ryan for martinis at Bar Bleu.

In the five months that they had known one another, their relationship had grown from a casual, no-strings-attached affair to something more serious. When they had first met, their get-togethers had taken place almost exclusively in the bedroom of Ryan’s apartment in Tarabya, a place where – Ebru was sure – he took other girls, but none with whom he had such a connection, none with whom he would be so open and raw. She could sense it not so much by the words that he whispered into her ear as they made love, but more by the way that he touched her and looked into her eyes. Then, as they had grown to know one another, they had spoken a great deal about their respective families, about Turkish politics, the war in Syria, the deadlock in Congress – all manner of subjects. Ebru had been surprised by Ryan’s sensitivity to political issues, his knowledge of current affairs. He had introduced her to his friends. They had talked about travelling together and even meeting one another’s parents.

Ebru knew that she was not beautiful – well, certainly not as beautiful as some of the girls looking for husbands and sugar daddies in Bar Bleu – but she had brains and passion and men had always responded to those qualities in her. When she thought about Ryan, she thought about his difference to all the others. She wanted the heat of physical contact, of course – a man who knew how to be with her and how to please her – but she also craved his mind and his energy, the way he treated her with such affection and respect.

Today was a typical day in their relationship. They drank too many cocktails at Bar Bleu, went for dinner at Meyra, talked about books, the recklessness of Hamas and Netanyahu. Then they stumbled back to Ryan’s apartment at midnight, fucking as soon as they had closed the door. The first time was in the lounge, the second time in his bedroom with the kilims bunched up on the floor and the shade still not fixed on the standing lamp beside the armchair. Ebru had lain there afterwards in his arms, thinking that she would never want for another man. Finally she had found someone who understood her and made her feel entirely herself.

The smell of Ryan’s breath and the sweat of his body were still all over Ebru as she slipped out of the building just after two o’clock, Ryan snoring obliviously. She took a taxi to Arnavutköy, showered as soon as she was home, and climbed into bed, intending to return to work just under four hours later.

Burak Turan of the Turkish National Police reckoned you could divide people into two categories: those who didn’t mind getting up early in the morning; and those who did. As a rule for life it had served him well. The people who were worth spending time with didn’t go to sleep straight after Muhteşem Yüzyil and jump out of bed with a smile on their face at half-past six in the morning. You had to watch people like that. They were control freaks, workaholics, religious nuts. Turan considered himself to be a member of the opposite category of person: the type who liked to extract the best out of life; who was creative and generous and good in a crowd. After finishing work, for example, he liked to wind down with a tea and a chat at a club on Mantiklal near the precinct station. His mother, typically, would cook him dinner, then he’d head out to a bar and get to bed by midnight or one, sometimes later. Otherwise, when did people find the time to enjoy themselves? When did they meet girls? If you were always concentrating on work, if you were always paranoid about getting enough sleep, what was left to you? Burak knew that he wasn’t the most hard-working officer in the barracks, happy to tick over while other, better-connected guys got promoted ahead of him. But what did he care about that? As long as he could keep the salary, the job, visit Cansu on weekends and watch Galatasaray games at the Turk Telekom every second Saturday, he reckoned he had life pretty well licked.

But there were drawbacks. Of course there were. As he got older, he didn’t like taking so many orders, especially from guys who were younger than he was. That happened more and more. A generation coming up behind him, pushing him out of the way. There were too many people in Istanbul; the city was so fucking crowded. And then there were the dawn raids, dozens of them in the last two years – a Kurdish problem, usually, but sometimes something different. Like this morning. A journalist, a woman who had written about Ergenekon or the PKK – Burak wasn’t clear which – and word had come down to arrest her. The guys were talking about it in the van as they waited outside her apartment building. Cumhuriyet writer. Eldem. Lieutenant Metin, who looked like he hadn’t been to bed in three days, mumbled something about ‘links to terrorism’ as he strapped on his vest. Burak couldn’t believe what some people were prepared to swallow. Didn’t he know how the system worked? Ten to one Eldem had riled somebody in the AKP, and an Erdoğan flunkie had spotted a chance to send out a message. That was how government people always operated. You had to keep an eye on them. They were all early risers.

Burak and Metin were part of a three-man team ordered to take Eldem into custody at five o’clock in the morning. They knew what was wanted. Make a racket, wake the neighbours, scare the blood out of her, drag the detainee down to the van. A few weeks ago, on the last raid they did, Metin had picked up a framed photograph in some poor bastard’s living room and dropped it on the floor, probably because he wanted to be like the cops on American TV. But why did they have to do it in the middle of the night? Burak could never work that out. Why not just pick her up on the way to work, pay a visit to Cumhuriyet? Instead, he’d had to set his fucking alarm for half-past three in the morning, show himself at the precinct at four, then sit around in the van for an hour with that weight in his head, the numb fatigue of no sleep, his muscles and his brain feeling soft and slow. Burak got tetchy when he was like that. Anybody did anything to rile him, said something he didn’t like, if there was a delay in the raid or any kind of problem – he’d snap them off at the knees. Food didn’t help, tea neither. It wasn’t a blood sugar thing. He just resented having to haul his arse out of bed when the rest of Istanbul was still fast asleep.

‘Time?’ said Adnan. He was sitting in the driver’s seat, too lazy even to look at a clock.

‘Five,’ said Burak, because he wanted to get on with it.

‘Ten to,’ said Metin. Burak shot him a look.

‘Fuck it,’ said Adnan. ‘Let’s go.’

The first Ebru knew of the raid was a noise very close to her face, which she later realized was the sound of the bedroom door being kicked in. She sat up in bed – she was naked – and screamed, because she thought a gang of men were going to rape her. She had been dreaming of her father, of her two young nephews, but now three men were in her cramped bedroom, throwing clothes at her, shouting at her to get dressed, calling her a ‘fucking terrorist’.

She knew what it was. She had dreaded this moment. They all did. They all censored their words, chose their stories carefully, because a line out of place, an inference here, a suggestion there, was enough to land you in prison. Modern Turkey. Democratic Turkey. Still a police state. Always had been. Always would be.

One of them was dragging her now, saying she was being too slow. To Ebru’s shame, she began to cry. What had she done wrong? What had she written? It occurred to her, as she covered herself, pulled on some knickers, buttoned up her jeans, that Ryan would help. Ryan had money and influence and would do what he could to save her.