скачать книгу бесплатно

The new Pope found a very grave situation in Italy. His independence was threatened from three different quarters. Profiting from disorders under Cesare Borgia, the key cities of Bologna and Perugia had rebelled against papal suzerainty, while the Venetian Republic had seized two more papal cities, Faenza, the majolica centre, and Rimini. Even graver was the French threat. In December 1503 the French lost the Kingdom of Naples to the Spaniards, but it soon became clear that they intended to make good that loss by expanding in northern Italy. Installed in the Duchy of Milan and controlling the politics of Florence, they were busy wooing Mantua from its suzerain the Emperor and Ferrara from its suzerain the Pope.

Julius decided to try and regain the papal cities first. In 1506 he ordered his vassal Guidobaldo of Urbino to raise 500 cavalry, but instead of entrusting them to a general Julius took command of them himself. It was a bold and startling step but, he believed, the only way to get results. Never before had a Pope ridden out of Rome at the head of an army in order to crush a rebellious city, and amid the general amazement none was greater than Gianpaolo Baglione’s, leader of the rebellion in Perugia. Though he was tough and unscrupulous—Machiavelli accuses him of parricide and incest—Baglione lost his nerve and rode forward to Orvieto, where he knelt before Julius, made his submission and offered a levy of troops. Julius forgave him: ‘But do it again and I’ll hang you.’

Julius then pressed over the Apennines for Bologna. It was bitter cold. As his mule-drivers stumbled through patches of snow, they swore and cursed; after each lapse Julius, who liked an oath himself, gruffly absolved them. The sixty-two-year-old Pope crossed torrents swollen by floods and clambered on foot over rocky slopes, but he would get up at dawn to lead the next day’s march. His energy was such that even the French king responded to his curt call for help against a rebel. Giovanni Bentivoglio, the rebel in question, reviewed his 6000 troops in the main square of Bologna and promised to fight to the death. But steadily the warrior Pope advanced, with his 500 cavalry and the aura of success at Perugia. It was too much for Bentivoglio. On 1 November 1506 he secretly slipped away, and ten days later Julius entered Bologna amid wildly cheering crowds. The following Palm Sunday the Pope returned to Rome, where he was welcomed by arches modelled on that of Constantine, decorated with statues and pictures. True, the arches were only of wood, but their inscriptions left nothing to be desired: ‘Tyrannorum expulsori’, ‘Custodi quietis’ and ‘Veni, vidi, vici.’

Julius next turned to Faenza and Rimini. First he tried diplomacy, but when he asked to see Venice’s title deeds to the two Adriatic cities, the Venetian ambassador replied with cool insolence: ‘Your holiness will find them written on the back of Constantine’s donation to Pope Sylvester of the city of Rome and the Papal State.’ Julius was furious and confided to Machiavelli, ‘To ruin the Venetians, I’ll join with France, with the Emperor, with anyone.’ This in fact is what he did. In December 1508 he united France, Germany and Spain in the League of Cambrai, ostensibly against the Turk, in fact against Venice, and on 14 May 1509 a powerful French army routed the Venetians near Cremona. Venice immediately handed over Faenza and Rimini to Julius.

The hardest part of Julius’s task now remained: to expel the French. Julius would repeatedly say how he longed for ‘Italy to be freed from the barbarians.’ If the term ‘barbarians’ savours more of the Roman Emperors than of a Pope, the concept of freeing Italy as a whole—not only the Papal States—was large-minded, and well in advance of most political thinking of the day.

Julius decided to join with Venice and attack the French through their main ally, Ferrara. He saw the war as a personal trial of strength between himself and Louis XII, ‘a cock who wants all the hens’. After wintering in Bologna, where he was struck down by serious illness and for a time lay delirious, Julius rose from his sickbed, mounted his horse and on 2 January 1511 rode out of the town in high spirits: ‘Let’s see who has the bigger testicles, the King of France or I.’

In a heavy snowstorm Julius joined his mainly Venetian army outside Mirandola, a key town of 5000 inhabitants 30 miles west of Ferrara, and defended by powerful walls, a moat and 900 troops, part French, part Ferrarese. Julius took command. Wearing armour under a white cloak with a fur collar, his head muffled in a sheepskin hood—‘he looks like a bear,’ wrote the Mantuan ambassador—Julius toured the lines in snow ‘half as high as a horse’, set up his nine cannon, and cursed the enemy: ‘Rebels! Robbers! That swine of a duke!’ He talked of nothing but capturing the town. Returning to his billet in a convent kitchen near the front line, he would chant over and over, ‘Mirandola! Mirandola!’, bringing a smile of admiration even to his half-frozen aides.

Twelve days later Julius was lying asleep when the convent kitchen received a direct hit from an iron cannon-ball ten inches in diameter. Two of his grooms were wounded but Julius was unhurt. He calmly changed his billet and sent the cannon-ball to the sanctuary of Loreto, where it is still preserved. When the second billet also came under fire, he moved back to the first. Meanwhile the English ambassador arrived and with all the innocence of a newcomer asked why Julius was fighting his compatriots and not the Turk. ‘We’ll talk about the Turk,’ Julius replied, ‘when we’ve taken Mirandola.’

Everything had to bend to the Pope’s iron will, even his gout-weakened body. In weather so cold that the Po had frozen hard, he was everywhere at once, cheering on his men, directing the cannon. At last the thick walls were breached. On 20 January the commander of Mirandola surrendered to Julius and was obliged to pay 6000 ducats for exemption from pillage. Not waiting to have the gates unbarred, Julius eagerly clambered in through the breach on a wooden ladder.

Julius’s success at Mirandola had a symbolic value out of all importance to the strategic value of the town. It showed that he was in deadly earnest about driving the French from Italy. He was thus able to secure allies. The end came in 1513, when 18,000 Swiss pikemen routed the French at the battle of Novara. The remnants of Louis’s army straggled home, while papal troops swept up the Po valley.

Julius had cleared Italy of the French and re-established his authority over the Papal States—two very important achievements. Furthermore, among the city-states abandoned earlier by the French were Parma and Piacenza, both rich, flourishing and strategically placed. Taking the measure of this new Pope who always seemed to win, they declared their wish to become papal cities. The Parmese ambassador addressed a speech to the consistory in which, with more emotion than logic, he recalled that Parma had originally been named Julia Augusta by Julius Caesar, and so ought to belong to the Pope, while a Parmese poet, Francesco Maria Grapaldi, made the same point hexametrically:

Te Regem, dominum volumus, dulcissime Juli:

Templa Deis, leges populis, das ocia ferro:

Es Cato, Pompilius, Cesar, sic Cesare major,

Sit qualis quantusque velit …

Julia Parma tua est merito, quae Julia Juli

Nomen habet, sed re nunc Julia Parma …

Sweet Julius, we want you for our king,

Instead of war you bring peace, religion and law:

Cato you are, Pompilius, a greater than Caesar,

Be whatever you choose to be …

Parma which once bore the name of Julius

Justly belongs to Julius the second …

—verses which won Grapaldi a laurel wreath from the Pope.

By annexing Parma and Piacenza Julius considerably strengthened the Papal States, while by expelling the French he brought a glow of pride to all Italians and especially to the Romans. On the evening of 27 June 1512 they celebrated the liberation of Genoa from French rule. The whole city burst into a flood of light. Fireworks shot up and cannon thundered from S. Angelo. The warrior Pope returned to the Vatican amid a procession of torches, while crowds shouted ‘Julius! Julius!’ ‘Never,’ said the Venetian envoy, ‘was any Emperor or victorious general so honoured on entering Rome as the Pope has been today.’

There were some, however, who refrained from cheering. They believed that by strengthening the Papacy in the things that are Caesar’s, Julius had weakened it in the things that are God’s. Michelangelo wrote a sonnet lamenting that ‘Chalices are turned into helmets and swords, Christ’s cross and thorns to spears and shields’, while Erasmus of Rotterdam, studying Greek in Bologna, had watched Julius’s triumphal entry in 1506 and described his feelings in The Praise of Folly, a book which was to be widely read in Germany:

Although in the Gospel the apostle Peter says to his divine Master: ‘We have forsaken all to follow you,’ the Popes claim that they possess a patrimony consisting of estates, towns, taxes, lordships; and when, driven by truly Christian zeal, they use fire and sword to hold on to this dear patrimony, when their holy, fatherly arm sheds Christian blood on all sides, then, elated at having humbled these wretches whom they call enemies of the Church, they boast of fighting for that same Church and defending the bride of Christ with apostolic courage.

The question was as old as the Papacy itself—should the Bishop of Rome imitate the lamb or the lion? If the former, he endangered the truth he had been commissioned to preserve; if the latter, he endangered Christian charity. Julius considered it imperative to preserve his political and economic independence, even by force of arms; others, like Erasmus, considered that the real challenge to the Papacy came over things that are God’s, and that the Pope should shame aggressive princes by turning the other cheek.

This, however, was not the only grievance to arise from Julius’s temporal and spiritual roles. Shortly after the Pope’s capture of Mirandola five of his cardinals—two Spaniards and three Frenchmen—rode away to join the French king. The fruits of their defection appeared on 28 May 1511, when Julius found a summons affixed to the door of the church of S. Francesco, near his lodgings in Rimini. Delegates of the German Emperor and the most Christian King summoned a Council of the Church, to be held on 1 September, an action which had become necessary, they said, in order to comply with the decree Frequens published by the Council of Constance in 1417, and neglected by the Pope, who had also failed to keep the solemn promise made in conclave.

The decree Frequens had indeed laid down that a Council should be held every ten years; there had been none since 1439. And Julius had indeed sworn to hold a Council by 1505; it was now 1511. Why had none been held? Why did the summons plunge Julius into gloom? Why was a Council anathema to him, as it had been to all Popes for seventy years? The answer lay in another decree, Sacrosancta, passed by that same Council of Constance, to the effect that the General Council, representing as it did all Christendom, derived its authority directly from Christ, hence everyone, the Pope included, was bound to obey it in all that concerns the faith.

This decree had given rise to two conflicting interpretations, both with honourable antecedents as far back as the twelfth century. One held that a Council was ‘above’ a Pope, while the other—the Curia’s view—argued that Sacrosancta had possessed merely an interim validity, from 1415 to 1417, when there had been either a doubtful Pope or no Pope at all.

The first interpretation was held by many men of goodwill who genuinely wished to reform the Church and believed that such reform could be achieved only by limiting the Pope’s absolute power. Unfortunately for the reformers, the same interpretation was also upheld by any and every prince at odds or at war with Rome, and their lawyers used it as ammunition to bombard the Popes politically. The political conciliarists outnumbered the genuine conciliarists and had, by their unscrupulousness, ruined the latter’s case with Rome. Indeed, while French lawyers were even now evolving a view of the Church little short of Gallicanism, the Papacy, in self-defence, had been hardening interpretation of Sacrosancta to the point where Pius II had actually excommunicated in advance anyone who dared to call a Council.

For two months Julius pondered how to deal with the summons. He thought of declaring the throne of France vacant and transferring it to Henry VIII of England, but this plan never went beyond the draft stage. Finally he decided on a much more effective measure. He himself summoned a Council, one he believed he could control, to assemble the following spring in Rome.

The pro-French cardinals duly met in November, at Pisa, supported by a special issue of French coins inscribed Perdam Babylonis nomen and, as expected, they declared Julius suspended. But their assembly was now no more than an ‘anti-Council’, and when Emperor Maximilian withdrew his support from it, no one took its activities seriously, since it was obviously just an instrument of French policy.

Julius’s Council, which assembled in the Lateran in April 1512, was attended mainly by Italian bishops, others being deterred by the war in north Italy. This strengthened Julius’s already strong hand still further. Indeed, like the Roman Emperors, he now had a personal bodyguard consisting of 200 Swiss soldiers, the Swiss being recognized as the best fighting men of the day. Julius completely controlled the Fifth Lateran Council to a degree hitherto unknown. Foreign ambassadors might address the bishops only with the Pope’s permission, and the Council was forbidden to issue decrees in its own name. All decrees took the form of papal bulls, signed by Julius.

To Julius himself and to the Curia this kind of Council seemed a victory, but like his victories on the battlefield, this too had a dark side. By his very strength Julius defrauded the Council of its rightful and necessary role. Instead of acting as a restraining influence on the Pope and voicing the anxieties of Christendom, it merely acted as the Pope’s instrument. This was to anger genuine conciliarists, notably in Germany. Furthermore, Julius left in abeyance the burning question of how Sacrosancta should be interpreted, so that in France, Germany and England many continued to believe that a Council was the Church’s final court of appeal. As late as 1534 Sir Thomas More, no mean scholar, could write to Thomas Cromwell that, while firmly believing the primacy of Rome to have been instituted by God, ‘yet never thought I the Pope above the general council.’

Julius was a successful soldier and a successful politician. But he was not only these things. At heart he seems to have been a man of peace, a member of the Order of St Francis of Assisi whom circumstances obliged to wage war. It is significant that his favourite pastimes were fishing and sailing, and that he liked gardens. Behind the Vatican he laid out the first considerable Roman garden since ancient times, in which aviaries and ponds were shaded by laurels and orange and pomegranate trees. He liked Dante and, lying ill in Bologna, listened to his architect friend Bramante read the Comedy aloud. He was very fond also of classical sculpture, his purchases including the Apollo Belvedere, the Tiber and the Torso del Belvedere. When the Laocoön was discovered on 14 January 1506 by a man digging in his vineyard near the Baths of Trajan, Julius bought it for 4140 ducats and had it conveyed on a cart to the Vatican along flower-strewn roads to the pealing of church bells.

Julius’s patronage of the arts has left a lasting mark on our civilization. It is intimately linked to his political activity, not only because his political successes kept Rome independent and provided money for the arts but because both express the Pope’s determination to assert his authority as an essential condition for preserving and proclaiming Christ’s message.

When he had been Pope for barely eighteen months and all his successes lay in the future, Julius conceived the idea of ordering his own tomb. It would be no ordinary resting-place but a colossal marble edifice decorated with many statues as fine as those in his own collection, a statement in contemporary terms of papal authority. But was there an artist to realize a work so grandiose? Julius, who had seen the Pietà in St Peter’s and certainly heard about the David, called on Michelangelo.

The former protégé of Lorenzo de’ Medici was then aged twenty-nine. Stocky, with a broken nose and curly hair, he was a man who spoke little, worked much and lived simply. He was generous to the poor and needy, and possessed of a strong trust in Providence: ‘God did not create us to abandon us.’ But towards his fellow-men he showed less trust. He was secretive and liked to work in a locked room. His sturdy Florentine independence tended to defiance, so that some found him ‘frightening’ and ‘impossible to deal with’.

Michelangelo at once answered the Pope’s summons. He possessed the largeness of vision to enter into Julius’s idea of a vast tomb, and drew a sketch of a free-standing rectangular monument, some 30 feet long and 20 wide, adorned with statues and rising in three zones to a catafalque. Julius liked the sketch, gave Michelangelo a contract at a salary of 100 ducats a month and sent him off to Carrara to obtain 100 tons of snow-white marble.

After eight months’ gruelling labour in the Carrara quarries Michelangelo set up a workshop in front of St Peter’s and prepared to begin the tomb. Julius however had meanwhile conceived an even more ambitious plan—the rebuilding of St Peter’s—and his passion for the tomb had cooled. In April he told a goldsmith and his master of ceremonies that he would not give another penny for stones, whether large or small. Michelangelo, worried, asked several times for an audience, but Julius, who was preparing to lay the foundation stone of the new St Peter’s, was too busy to see him. Finally, on 17 April 1506, Michelangelo was turned out of the palace.

This rebuff both angered and alarmed him. He sensed secret enemies: ‘I believed, if I stayed, that the city would be my own tomb before it was the Pope’s.’ In 1494 at the time of the French invasion he had fled Florence, and now once again he took flight, selling his scanty possessions and galloping full speed for Florence, pursued by five of the Pope’s horsemen. Once safe on Florentine soil, he wrote to Julius: ‘Since your Holiness no longer requires the monument, I am freed from my contract, and I will not sign a new one.’

In November 1506 Julius entered Bologna in triumph and, not for the first time, invited Michelangelo to re-enter his service. Persuaded by the Florentine Government that it would be patriotic to do so, Michelangelo swallowed his pride and rode to the brown-brick papal city. No sooner had he pulled off his riding-boots than he was escorted to the Palace of the Sixteen, a rope round his neck as a symbol of repentance. Here Julius eyed him sternly. ‘It was your business to come to seek us, whereas you have waited till we came to seek you,’ alluding to his march north.

Michelangelo fell on his knees. He had left Rome, he said, in a fit of rage, and how asked pardon. Julius made no answer, but sat with his head down, frowning. Finally the grim silence was broken by a courtier-bishop.

‘Your Holiness should not be so hard on this fault of Michelangelo; he is a man who has never been taught good manners. These artists do not know how to behave, they understand nothing but their art.’

In a fury Julius turned on the bishop. ‘You venture,’ he roared, ‘to say to this man things that I should never have dreamed of saying. It is you who have no manners. Get out of my sight, you miserable, ignorant clown.’ He struck the bishop with the stick he always carried, and to Michelangelo reached out his hand in forgiveness.

Julius then explained that he wanted a statue of himself in bronze: no ordinary statue, but one 14 feet high—twice the height of the David in Florence. How much would it cost?

‘I think the mould could be made for 1000 ducats, but foundry is not my trade, and therefore I cannot bind myself.’

‘Set to work at once,’ said Julius.

Michelangelo lodged in a poor room, where he slept in the same bed with three helpers for casting the statue. At the end of June they began the bronze-pouring. Technically so large a work presented many problems, and only the bust came out, the lower part sticking to the wax mould. Michelangelo started again and in February 1508 succeeded in delivering a perfect statue weighing six tons. It depicted Julius in full pontificals, the tiara on his head, the keys in one hand, the other raised in blessing. The huge bronze admirably typified the more-than-lifesize Pope, but its dimensions are probably to be explained by Julius’s interest in the Emperors, so many of whom had erected colossal statues of themselves: Nero’s had been 150 feet high. Doubtless Michelangelo was struck by the difference between Julius’s concept of a ruler and that of his former patron, Lorenzo de’ Medici, always shunning the limelight and insisting that he was merely one citizen among many; yet both concepts came from classical antiquity.

The statue caused wonder among the people of Bologna. One man asked Michelangelo which he thought was bigger, the statue or a pair of oxen, to which the sculptor, who did not suffer fools gladly, replied: ‘It depends on the oxen. You see, an ox from Florence isn’t as big as one from Bologna.’ Set in position above the door of the church of S. Petronio, the statue of Julius did not remain there long. During a revolution in December 1511 it was toppled down, broken amid gibes and, save for the head, recast as a culverin by Alfonso, Duke of Ferrara, who called it La Giulia. So the statue intended to honour Julius ended up as a gun pointed against him.

A friendship was ripening between the Pope and Michelangelo. Though the Pope was twice the sculptor’s age, both were virile, serious, energetic and possessed of breadth of vision. Back in Rome at the beginning of 1508, Julius conceived the plan of getting Michelangelo to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel with designs, and the lunettes with large figures: at present the ceiling was painted blue with gold stars. Michelangelo protested that he was a sculptor, not a painter, and would prefer to start carving the Pope’s tomb. But finally he consented.

Michelangelo found himself to some extent limited by the existing decoration. The side walls depicted scenes from the life of Moses facing comparable scenes in the life of Christ: the history of man under the Law, then under Grace. Michelangelo’s first idea was to take man’s history a stage further by painting the Apostles in the lunettes. After making several sketches, he decided that this decoration would be ‘poor’. ‘Why poor?’ asked Julius. ‘Because the apostles were very poor.’ Evidently Michelangelo meant austere and humble, whereas his own particular gift, as he knew by now, was for celebrating the power and beauty of the human body.

Julius and Michelangelo then looked for another subject. Now Lorenzo de’ Medici’s circle in Florence had claimed that there exists an underlying harmony between Hebrew, pagan and Christian thought, and this view was widely held by humanist scholars in Rome. Julius was sympathetic to it, and Michelangelo had been brought up in it. According to this view, the world of Greece and Rome which was being rediscovered in all its splendour was not a rival but an ally of truth. Just as the Prophets of Israel and the Sibyls from pagan darkness could speak of the true God, so did the nudes of Polyclitus make an authentic statement about beauty, therefore about God. Michelangelo had already hinted at such an approach in his Doni Holy Family, where the Christ-child is portrayed against a background of nude youths in the classical style, thus suggesting that Christianity fulfils the beauty and promise of antiquity. This was evidently the thinking that led Julius and Michelangelo to agree on a new subject: Scenes from Genesis, that is, the history of man before the giving of the Law; treated, however, prophetically. The Scenes would look forward, through Prophets, Sibyls, the ancestors of Mary and nude figures in the classical style symbolizing natural man, to the Incarnation of Christ. But instead of confining these scenes to the lunettes and painting the ceiling with ‘the usual adornments’, Michelangelo offered to paint the whole surface with figures, more than 10,000 square feet.

This was seven times the area Giotto had painted in the Scrovegni Chapel and it was, as contemporaries recognized, a superhuman task. But here precisely lay its appeal for Julius, who delighted in campaigns that daunted his closest advisers, and for Michelangelo, who had learned from Ficino’s neo-Platonism that an artist receives guidance from God to organize and complete His universe. That summer Julius gave Michelangelo a contract for the ceiling at a fee of 6000 ducats, all paints chargeable to the artist.

Now Michelangelo had never painted a fresco in his life. So while completing the first cartoons and supervising the erection of wooden scaffolding, he sent to Florence for his young studio assistants, hoping that their technical knowledge would help him. But their designs failed to satisfy him. One morning he made up his mind to scrap everything they had done. He shut himself up in the chapel and refused to let them in again.

He was alone with the immense bare vault. Climbing the ladders to the top of the scaffolding, he began work on the first scene, The Flood. He smeared the ceiling above him with a fine layer of intonaco—a plaster composed of two parts volcanic tufa and one part lime, stirred together with a little water. He chose tufa instead of the usual beach sand because it gave a rougher, less white surface. On this layer of intonaco he placed the appropriate piece of the cartoon, smoothing it quite flat and fastening it with small nails. He then dusted powdered charcoal over it. The charcoal passed through holes in the cartoon pricked beforehand and adhered to the moist intonaco, leaving the outlines of the figures. Later he was to omit the charcoal dusting and prick the outlines directly on to the plaster with an awl. He then unfastened the cartoon and began to paint. He had to be quick, especially in summer, when plaster dried in a couple of hours, and accurate too, because mistakes could not be rectified.

In summer the air immediately under the vault was suffocating and the plaster dust irritated his skin. Watercolours dripped on to his face and even into his eyes. He worked standing, looking upwards. In a burlesque sonnet illustrated with a sketch he says that the skin on his throat became so distended it looked like a bird’s crop. The strain was such that after a day’s work he could not read a letter unless he held it above him and tilted his head backwards.

When he had finished The Flood, Michelangelo dismantled that part of the scaffolding and looked at it: from below. He saw that the figures were too small and determined to continue on a broader scale, converting the form, mass and stresses of the vault into artistic values. But would he be able to continue? ‘It has been a year since I got a penny from this Pope,’ he wrote on 27 January 1509, ‘and I don’t ask him for any, because my work isn’t going ahead well enough for me to feel I deserve it. That’s the trouble—also that painting is not my profession.’

Payments however did begin, and when Julius left on his Ferrara campaign again abruptly stopped. At the end of September 1510 Michelangelo found he had no money to buy pigments, so laying his brushes aside he rode the 250 miles to Bologna and persuaded Julius to resume payments. In October he was paid 500 ducats in Rome. But presently money again dried up, and with it his paints. Michelangelo rode a second time to Bologna, and again a hard-pressed Julius decided that the ceiling must come before everything else. In January 1511 Michelangelo had been paid and was back on his scaffolding.

When Julius returned to Rome he naturally wanted to see how work was progressing. Several times he climbed up, with Michelangelo’s strong hand supporting him on the highest ladder, to study the latest scenes, and each time he would ask, ‘When will you finish?’ Michelangelo would reply, ‘When I can.’ He had become more assured now and was painting figures in the lunettes without any cartoon. But when Julius received that answer for the third time, in autumn 1512, he exploded into one of his furies. ‘Do you want me to have you thrown off the scaffolding?’ Though he would have liked to add some touches of gold and ultramarine, Michelangelo saw that the Pope would not wait any longer. So he signed the work, but instead of putting his name he painted the Greek letters Alpha and Omega near the prophet Jeremiah, thus attributing any merit in the ceiling to God, through whose assistance it had been begun and ended. Evidently Michelangelo saw himself in Platonic terms, like the Sibyls and Prophets, as an instrument through whom God made manifest His beauty.

The scaffolding was dismantled and without even waiting for the dust to settle Julius hurried to gaze on the finished whole. The expectations of three and a half years were not disappointed. Julius liked the ceiling very much indeed, as Michelangelo wrote to his father, and ordered it to be shown to the public on 31 October 1512, the Vigil of All Saints, the feast which celebrates the human race glorified in heaven. All Rome flocked to see it, says Vasari, and one can imagine the effect on them of so vast a work, containing 343 figures, some of them as much as eighteen feet high, in its pristine colours of rose, lilac, green and grey.

At a literal level the ceiling is straightforward enough. Five scenes of Creation are followed by the Fall and Expulsion, the Sacrifice of Noah, the Flood, and Noah’s Drunkenness, that darkening of the spirit which was later to be righted when God gave the Ten Commandments to Moses: since that event was already depicted on the wall below, the ceiling dovetailed into the rest of the chapel. Below the Scenes from Genesis are twelve Prophets and Sibyls, who by their utterances look forward to the Incarnation; while in the spandrels and lunettes are the ancestors of Christ.

In depicting these events, Michelangelo makes man the hero. In the centre of the ceiling and dominating the whole is the figure of Adam. Medieval mosaicists had shown God bending over him and breathing into his body a soul, either as rays or as a little Psyche with butterfly wings, psyche being Greek for both soul and butterfly. Breaking with these and other traditions, in an image of genius Michelangelo shows God imparting life through his own and Adam’s outstretched fingers. And this Adam is an image of the God who is creating him, a perfect being unflawed by sin. His body is beautiful and unblemished. It is just such a body as Christ will assume, and which we shall have in heaven. Even after the Fall, it is the most perfect of created things. It is also the most versatile. In the rest of the ceiling Michelangelo celebrates the power and beauty of the human body in a wide variety of actions. He depicts titanic, muscular figures engaged in tasks that test them to the limit. He shows them exercising not faith, hope and charity which have not yet arrived in the world, but classical virtus, virility. They impose their will on events through bodies that drive like tornados, torrents or avalanches. Even as Prophets and Sibyls they are not passive, they strain and twist and writhe in order to glimpse the hidden mystery, then to express it. As the ancestors of Mary, they struggle to protect their children, that long stream of expectant humanity flowing from Adam to Christ.

Michelangelo’s titanic grand design is enriched by innumerable perceptive details. The Ignudi, the nude male figures who represent man in classical times, carry festoons of oak leaves and acorns, as a sign of the golden age in which they lived, and also in allusion to Julius whose family blazon was the oak tree and who was hailed by many as a restorer of the golden age. Again, the Brazen Serpent erected by Moses to heal the people of Israel harks back ironically to the serpent coiled round the Tree of Life. Classical borrowings too add to the theme of harmony between pagan and Christian thought. In the Expulsion, for example, Adam raises his hands in a gesture of defence from the chastising angel and this is a mirror image of Orestes pursued by the Furies in an antique bas-relief. These and many other details give the ceiling an incomparable imaginative richness.

When the Sistine ceiling was finished, Julius, who the previous year had suffered an almost fatal illness, began to take a renewed interest in his tomb. Michelangelo’s design called for three tiers, the lowest where Julius’s body would lie, a middle part decorated with seated figures of Moses and St Paul, and an uppermost part on which two angels would support a figure of the Pope sleeping. Julius now set Michelangelo to work on the statue of Moses, whom the Popes considered a prototype of themselves.

Michelangelo’s Moses is close to the Sistine figures both in time and spirit. He is an incarnation of man’s driving will, and since his own will was immensely powerful so must be his body. Whereas in the David Michelangelo had exaggerated the size of the head, to signify that the young warrior’s triumph had not been one of mere strength, here he exaggerates the size of the arms, boldly marking their veins and sinews. The bearded prophet holds the tablets of the Law in his muscular hands and his gaze, defiant and terrible, was perhaps suggested by Julius in anger. The two horns on his head are explained by the Vulgate’s mistranslation of a passage from Exodus: ‘his brow became horned while he spoke to God’, whereas the Hebrew has ‘radiant’. The horns were a traditional way of designating Moses in art and even in mystery plays. A last curious point is that in the beard Michelangelo has carved small portraits of Julius and himself in profile, evidently to commemorate their collaboration in the tomb.

During 1513 Michelangelo also made two statues for the lowest part of Julius’s tomb. It is uncertain what they represent. Vasari says ‘provinces subjugated by the Pope and made obedient to the Apostolic Church’; Condivi says they are two of the three arts, Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, ‘made prisoners of death with their patron, since they would never find another Pope to encourage them as he had done.’ The two youths, one resigned, the other struggling vainly to free himself, transcend any particular allegory to become symbols of human captivity and, as such, they reveal another side of Michelangelo’s character. The body he exalted in the Moses and the Sistine ceiling was also the body that held him personally captive, for Michelangelo instinctively preferred the love of men to the love of women. Theoretically man’s body was one with the cosmos, in fact it was not.

Michelangelo left the two prisoners unfinished. Several explanations present themselves. He may have left them thus because the relief is more pronounced in unfinished work, or because there is a sense of movement, as though the form were striving to free itself from the block. Or he may have wished them to resemble certain antique statues, such as the Torso del Belvedere, which are more expressive when worn and truncated, or he may have intended to associate his figures, through the rough stone, with the cosmos. But if the prisoners are understood to express a temperamental dilemma that never was and never could be resolved, that perhaps provides the most satisfactory explanation of why they were left unfinished.

The tomb too was left unfinished, at least in the form Julius intended, so that later, after the Pope’s death, when lesser men whittled away the grand design, these prisoners were allowed no part in it and, like Julius himself in earlier life, went into exile in France. It was Julius however who commissioned them; they belong beside the Moses, and they remain the most moving testimony of all to the collaboration of a great artist and a great patron.

On 26 November 1507 Julius made one of his lightning pronouncements. He could not bear to live in the Appartamento Borgia any longer, continually reminded of ‘those Spaniards of cursed memory’ by Pinturicchio’s frescoes of Alexander VI, Lucrezia and the rest. He decided to move to four rooms on the second floor. At once he called in Perugino, Lorenzo Lotto and others to begin decorating the first of the Stanze, as they are called, and Raphael too when he arrived in Rome at the end of 1508. Perceiving the young man’s genius, Julius dismissed the other painters and entrusted the frescoes to Raphael alone.

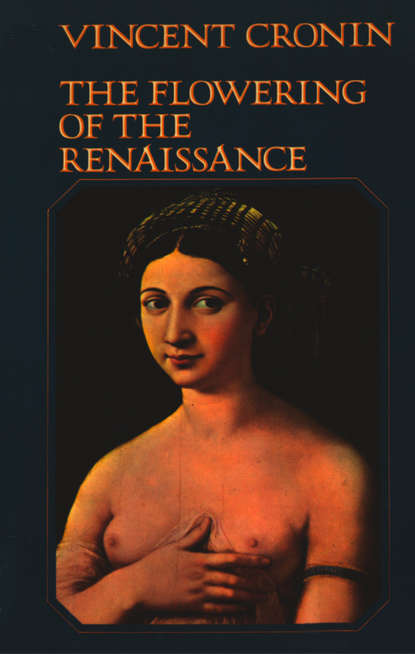

Raffaello Sanzio was then aged just twenty-six, a slim man with a thin face, dark eyes, slender neck and delicate, probably consumptive, appearance. His sweet, equable character won him everyone’s affection. For many years he was in love with La Fornarina, the baker’s daughter whose large dark eyes and rather round face appear in many of his works, notably the Sistine Madonna, in which Julius is also portrayed; it was perhaps for love of her that he put off marriage to Cardinal da Bibbiena’s wealthy niece.

Julius imparted to Raphael his plan for the Stanze. He wished them to proclaim the absolute power of the Pope, spiritual as well as temporal, the spiritual power being exemplified in the doctrine of the real presence of God in the Blessed Sacrament. Julius had a particular devotion to the Eucharist—in 1508 he took the unusual step of joining the Confraternity of the Blessed Sacrament, a group of Romans who wished to honour God in the Eucharist by providing a torch-carrying escort whenever viaticum was carried to the sick. The Real Presence had been denied by the Bohemians when they separated themselves from Rome and by their theologians was currently under attack.

The Sistine Chapel had proclaimed the Incarnation as the fulfilment of pre-Christian striving, and the most important of the Stanze, the library, proclaims the Real Presence as the fulfilment or culmination of other kinds of truth. First, there is the truth of law, symbolized by the Pandects and the Decretals; second, poetic truth, depicted under the form of Apollo and the Muses; third, philosophic truth, depicted in a fresco larger than the preceding two, known as The School of Athens. In a hall dominated by statues of Apollo and Pallas, symbolizing Reason, the philosophers of antiquity ponder, dispute and finally, in the persons of Plato and Aristotle, reach heights where agreement is possible. Opposite this fresco is one depicting the revealed truth of the Real Presence. Doctors of the Church, saints and popes down the centuries, even Julius’s favourite Dante, are shown paying tribute to the Blessed Sacrament exposed in a monstrance, above and converging on which are the Three Persons of the Trinity attended by the Blessed and by angels.

In the next room, his bedroom, Julius chose to state the truth of the Real Presence in terms of an actual historical incident. A certain Bohemian priest had doubts about transubstantiation; in order to try and overcome them he made a pilgrimage to Rome. On the way, at Bolsena, while celebrating Mass, he saw the host in his hand oozing blood. He tried to hide it in the corporal, but the blood seeped through, leaving a cross-shaped mark on the linen. Following on this miracle, the feast of Corpus Christi had been instituted, and the blood-stained corporal was preserved in Orvieto, where Julius had seen and venerated it.

In Raphael’s rendering of this dramatic scene a hundred years are bridged in order to show Julius at a prie-dieu watching the miracle take place. He is attended by Swiss guards in the handsome striped blue and orange uniforms he had commissioned Michelangelo to design for them. The mural is not only a beautiful and original composition: it is a notable attempt to arrest heresy with paint.

Raphael had arrived in Rome a somewhat languorous artist, and when he attempted to depict people in action as in the Deposition of 1507 he lapsed into a lymphatic formalism. But Julius’s Stanze are robust and vigorous. The School of Athens, in particular, is crowded with energetic figures, notably the portrait of Leonardo da Vinci as Plato. The aging Pope seems to have imparted to the younger man not only his vision of the underlying harmony of classical and Christian truth, but also some of his own unflagging energy.

Julius’s patronage extended also to architecture. In this field the Roman Emperors had been pre-eminent, and it was natural for a Pope who in some degree saw himself as their successor to engage as his architect an expert on the imperial style. This man—the third artist of genius employed by Julius—was Donato d’Angelo Lazzari, known as Bramante from his eagerness in seeking out commissions, bramare meaning to solicit. Born in Lombardy in 1444, Bramante was built like a wrestler, with a forceful muscular head and curly hair. Two little facts are known about him: he had a passion for pears and he liked giving supper parties at which he would entertain his friends by improvising on the lyre. However, like many a convivial Italian, Bramante saw himself as essentially sad and solitary, and wrote sonnets to proclaim the fact. He was a friend of Raphael, but did not get on with Michelangelo.

Julius commissioned Bramante to lay out the great garden mentioned earlier, which stretched from the Vatican proper to the thirteenth-century Belvedere villa 300 yards north, to enclose the garden with two long straight galleries, and to reconstruct the villa along the lines of the imperial Temple of Fortune at Palestrina. This reconstruction called for a two-storeyed façade, having for its centre a vast semi-circular niche with flanking walls of blind arcades, the whole being approached by a double ramp ascending in terraces. Although the full plan was never realized, enough was built to set a classical mark on the largely medieval Vatican Palace. The façade of the Belvedere villa was remodelled, and the gallery on the east side built—the other had to wait fifty years. Julius decorated the gallery’s open colonnades with frescoes representing the chief Italian cities—another example of his feeling for Italy as a whole—and in the courtyard of the Belvedere villa displayed his Apollo, the Laocoön and other works of classical sculpture.

The culmination of Julius’s life both as Pope and patron was the rebuilding of St Peter’s. The idea of a great new basilica, which had been shelved since the death of Nicholas V, naturally appealed to Julius. Not only was the old basilica decrepit, but on men who had come to appreciate the best imperial monuments, its style jarred, notably the vast atrium separating the entrance from the basilica proper, and the crude roof of open timber. Julius wanted a building which would, as he worded it in a bull, ‘embody the greatness of the present and the future’. This could be achieved of course only by turning to the greatness of the past.

‘The dome of the Pantheon over the vault of the Temple of Peace’, is how Bramante described his concept of the new St Peter’s. Like the humanists of Florence, Bramante considered a centrally-planned church most suited to express the perfection of God, and his first design took the form of a Greek cross. However, in order to retain the tomb of St Peter under the dome—Julius would not hear of it being moved—he found that the arms of the cross would have to be shortened unduly. He then submitted a quite different project. Inside, it called for a traditional nave and aisles, outside for a portico entrance derived from the Pantheon, a dome marked with concentric rings like those on the Pantheon also, and four secondary domes at the intersection of the arms. While numerous towers gave the impression of complexity, unity was maintained by heavy cornices extending throughout on the same level.

Julius was not easy to please. He had already turned down plans by Sangallo and Rossellino. But he liked Bramante’s new design, approved it in October 1505, commissioned Caradosso to strike a medal depicting its elevation, and ordered work to begin. The soil was marshy, and workmen had to dig down 25 feet before striking solid tufa. On Low Sunday 1506 Julius climbed down to that level to bless and set in place the white marble foundation stone—twelve inches by six by one and a half—inscribed: ‘Pope Julius II of Liguria in the year 1506 restored this basilica, which had fallen into decay.’

Thereafter not a moment was lost. Julius proclaimed an indulgence within Italy in order to raise money for the cartloads of honey-coloured travertine which workmen carted from the Tivoli region, marble from Carrara, puzzolane from around Rome, lime from Montecello. Henry VIII sent tin for the roof and Julius, who knew his man, thanked him with barrels of wine and hundreds of Parmesan cheeses. Costabili of Ferrara wrote on 12 April 1507: ‘Today the Pope went to St Peter’s to inspect work. I was there too. The Pope brought Bramante with him, and said smilingly to me, “Bramante tells me that he has 2500 men on the job; one might hold a review of such an army.”’

A single misjudgmcnt marred the great undertaking. Bramante was so fervent a classicist that he found no beauty in Constantine’s basilica. He had the medieval candelabra, icons and mosaics destroyed, though fortunately Giotto’s Navicella escaped his workmen’s hammers. He earned the title of ‘il Ruinante, and a lampoon pictures the architect arriving at the gates of heaven, where St Peter reproaches him with destroying his church and tells him to wait outside until it is rebuilt; Bramante coolly replies that he intends to spend his time replacing the narrow path to heaven by a well-paved Roman highway.

By the end of his reign Julius had spent 70,653 ducats on St Peter’s. Four great piers rose to the level of the dome and the arcades which were to bear the dome were partly finished. The walls of the projecting choir were also complete, and vaulting begun on the south transept. Building would continue through many reigns, and modifications would be made to Bramante’s designs, but to Julius must go the honour of having chosen so grand a plan and in a mere seven years carried the work so far.

It is difficult to believe that Julius crowded so much action and activity into a pontificate of less than, ten years. It was exhausting work for a man in his late sixties to launch out into so many new schemes, and in Raphael’s portrait, probably of 1512, the Pope’s eyes are downcast and tired, and his powers seem beginning to fail. In the following February he was prevented by illness from attending the fifth session of the Lateran Council. He lay in the room Raphael had decorated for him, close to the new Belvedere, close also to the Sistine Chapel. He could claim to have fulfilled his task of reasserting papal authority and proclaiming Christianity in contemporary terms through the techniques that had most advanced in his day: sculpture, painting and architecture. Indeed the new Christian Rome could now compare favourably with the classical, hence the title of Albertini’s little book, published in 1510: The Marvels of Modern and Ancient Rome. Only the great tomb was not ready. Julius left 10,000 ducats for its completion, and finally, thirty-one years later, in a much reduced form, it was to hold his mortal remains, not, as he would have liked, in St Peter’s, but in S. Pietro in Vincoli.

On 20 February 1513 Julius II died. He was described by the Florentine historian Guicciardini, no lover of the Papacy, as ‘worthier than any of his predecessors to be honoured and held in illustrious remembrance.’ The Romans agreed. ‘I have lived forty years in this city,’ wrote Paris de Grassis, his master of ceremonies, ‘but never yet have I seen such a vast throng at a Pope’s funeral. The guards could not control the crowds as they forced their way through to kiss the dead man’s feet…. Many even to whom the death of Julius might have been supposed welcome for various reasons burst into tears, declaring that this Pope had delivered them and Italy and Christendom from the yoke of the French barbarians.’

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_2943fa45-46aa-5b47-8039-56c0c5ab585d)

After Caesar, Augustus (#ulink_2943fa45-46aa-5b47-8039-56c0c5ab585d)

I HAVE THREE SONS,’ Lorenzo de’ Medici used to say, ‘one foolish, one good and one clever.’ The clever son was born in the Palazzo Medici on 11 December 1475 and christened Giovanni Romolo Damaso. He was ‘brought up in a library’—the phrase is his own—learning Latin and Greek from Poliziano, imbibing the broad-minded philosophical ideas of Pico and Ficino, laughing at Pulci’s burlesque Morgante, watching Michelangelo shape a block of marble in the Palazzo garden. Destined by Lorenzo for a career that would bring Florentine principles to the capital of Christendom, at seven he received minor orders, at twelve the abbey of Monte Cassino, at seventeen a Cardinal’s hat. He studied canon law at the University of Pisa but before he could graduate or learn theology Charles VIII rode in. With his ‘foolish’ brother Piero he was driven from Florence and spent an unhappy period wandering in Germany and France. In 1497 he returned to Rome and three times served as Legate, on the last occasion being captured by the French at the Battle of Ravenna. He was imprisoned in a pigeon-cote from which, however, he escaped hidden in a basket. He attended the conclave on a litter, suffering from an anal fistula, which between scrutinies his doctor lanced. In a long, commendably unsimoniacal election, during which the sacred college was reduced to a vegetable diet, he was chosen in preference to Raffaello Riario—whom Lorenzo had saved from lynching at the time of the Pazzi plot—mainly by the younger cardinals, who did not want a second nephew of Sixtus IV. He took his name in evident allusion to Leo the Great, who had kept the Hun from Rome—but by diplomacy, not arms. He was still in minor orders and was ordained priest four days after his election.

The new Pope was above middle height, broad-shouldered and portly. His head was set on a short neck, and the cheeks were puffy. He was short-sighted—hence the magnifying-glass in Raphael’s portrait, and his enemies’ quip: ‘Blind cardinals have chosen a blind Pope.’ He had shapely white hands and liked to show them off, as the fashion was, with diamond rings. He perspired easily and during long ceremonies would be seen mopping his face and hands. He also suffered from the cold, and in severe weather would wear gloves, even to say Mass.

Though he was not robust, Leo was a happy man who liked to make others happy. He was generous to a fault and whenever he could grant a favour did so. He had inherited Lorenzo’s easy, tactful manner, but not his daring. In politics, for instance, Leo moved cautiously—hence the nickname given him by Julius: ‘Your Circumspection’; and once when fire broke out in the Vatican his alarm was judged excessive. Otherwise he had plenty of self-control. He fasted twice a week, and his name was never associated with any woman. He took his religious duties seriously, said his office every day, and once, on ascending the Scala Sancta, was heard to beg God’s indulgence for not climbing it on bended knee like the poor women of Rome. As his papal motto he chose the first verse of Psalm 119: ‘Happy those who are irreproachable in their life, who walk in the way of the Lord.’ The linking of happiness and virtue is typical of the man.

Soon after his election Leo is reported to have said to his brother, ‘Let us enjoy the Papacy since God has given it to us.’ Though first recorded by a Venetian two years after the event, the mot may well be authentic; if so, it is much less ingenuous than it sounds. Leo had been raised in a civic-minded and civilized Republican family, and enjoyment for him meant extending through patronage the principles of Christian humanism. His ambition as Pope was to renew Christianity through learning, literature and the arts. Rome in particular he intended to become a great civilized city, a worthy successor to the Rome of Virgil and Horace. The humanists understood this when they hailed Leo on the morrow of his election with the phrase: ‘After Caesar, Augustus.’

To civilize Rome was no small ambition. Despite Julius’s building, the city was still an inhumane and bloodthirsty place. Within memory a Pope’s son had been stabbed to death, and when someone who had seen the body being thrown into the Tiber was asked by the magistrates why he had not revealed the fact, he replied that murder was an everyday occurrence and it had never dawned on him to go to the authorities. With advances in medicine poison was now being increasingly and more subtly used; indeed it was a Florentine cardinal, Ferdinando Ponzetti, who in 1521 published the first handbook on poisons. Leo himself was to be the object of a plot headed by Alfonso Petrucci, who disapproved of papal policy in Siena, and five other cardinals. They planned that Leo’s fistula should be treated with ointment containing poison. Through an intercepted letter the plot was discovered and quashed, but the incident puts into relief the ambitious nature of Leo’s programme.

As an essential condition for civilizing Rome, Leo had to preserve the peace won for Italy by Julius II’s wars. Under their ambitious young king, François I, the French again crossed the Alps in 1515, while the election of Charles V as Emperor in 1519 united in a formidable coalition Spanish with German strength. Applying Lorenzo’s principle of the balance of power, Leo skilfully got the Emperor to expel François from Milan and thereafter played off the two rulers against each other. He also forestalled any future French schism by the Concordat of 1516. This laid down that the Pope and the King of France were jointly to appoint bishops; it made the King to a certain extent overlord of the French Church, but also at the same time its natural protector. For three hundred years Leo’s Concordat was to ensure that French kings would, if only from self-interest, remain loyal to Rome.

Leo began his work of civilizing Rome by refounding the Sapienza, which because of war had been inoperative for thirty years. He did so on a lavish scale. He appointed no less than 88 professors at salaries totalling 14,490 ducats, part of which, in case of sickness, was payable to their dependants. With his usual broad-mindedness he increased the range of faculties: civil law was the largest—Leo lifted the ban on clerics studying this subject—then came rhetoric, philosophy and theology, medicine, canon law, Greek, mathematics, astronomy and botany. Leo rejected the chauvinism implicit in Pomponius Laetus’s boast that he declined to learn Greek for fear of spoiling his Latin accent; the new Pope summoned Giovanni Lascaris, Lorenzo’s former librarian, to strengthen the Greek faculty, and subsidized Varino Favorino, who had once taught him Greek, in his task of composing an important Greek lexicon. Leo also founded a Greek press, attached to the Sapienza, which published scholarly editions of Didymus’s Commentaries on Homer, Porphyry’s Homeric Questions, and the Scholia of Sophocles’s tragedies. He encouraged Cardinal Ximenes in his five-language edition of the Bible, and shipped to him in Toledo boxes of precious Greek manuscripts chained and padlocked. Hebrew studies Leo also promoted by founding a chair of Hebrew and a Hebrew press. When the German scholar Johann Reuchlin was denounced to Rome by the Dominicans for advocating the study of all Hebrew books, even those hostile to Christianity, Leo dropped the case, a gesture which German humanists interpreted as a blessing on free enquiry.

Leo’s most imaginative scheme concerns the Latin language. In common with most of his educated contemporaries Leo had a great personal liking for classical Latin and spoke it fluently, but where others saw Latin only as a means of penetrating the admired world of Cicero and Virgil, Leo saw it as a means of attaining through a study of origins to a deeper self-consciousness. With this in mind he decreed that every meeting of the Conservators—the municipal Council of Rome—should open with a speech in Latin by a native Roman about distinguished Roman citizens of past ages. But this was only one half of Leo’s plan for Latin. He wished also to make the language of Cicero the universal language of educated men, and as such, an instrument of civilization and peace. Just as the Roman Emperors used Latin to unite their Empire—Latin, claimed Valla, had more power than all the legions combined—so he would use it to unite Christendom. The very first thing Leo did on leaving the conclave was to appoint as his domestic secretaries the two most elegant Latin stylists alive—Jacopo Sadoleto of Modena and Pietro Bembo of Venice—with instructions to draft all the Pope’s official correspondence, within and without Italy, in Ciceronian Latin.

With the same aim in mind Leo encouraged the writing and improvisation of Latin verse. At meals he liked to swap impromptu repartee with Camillo Querno, a prolific versifier with long flowing hair, known as ‘the archpoet’:

Querno: Archipoeta facit versus pro mille poetis.