скачать книгу бесплатно

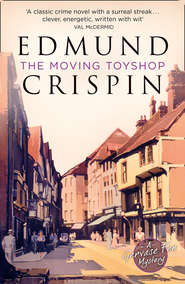

The Moving Toyshop

Edmund Crispin

As inventive as Agatha Christie, as hilarious as P.G. Wodehouse - discover the delightful detective stories of Edmund Crispin. Crime fiction at its quirkiest and best.Richard Cadogan, poet and would-be bon vivant, arrives for what he thinks will be a relaxing holiday in the city of dreaming spires. Late one night, however, he discovers the dead body of an elderly woman lying in a toyshop and is coshed on the head. When he comes to, he finds that the toyshop has disappeared and been replaced with a grocery store. The police are understandably skeptical of this tale but Richard's former schoolmate, Gervase Fen (Oxford professor and amateur detective), knows that truth is stranger than fiction (in fiction, at least). Soon the intrepid duo are careening around town in hot pursuit of clues but just when they think they understand what has happened, the disappearing-toyshop mystery takes a sharp turn…Erudite, eccentric and entirely delightful – Before Morse, Oxford's murders were solved by Gervase Fen, the most unpredictable detective in classic crime fiction.

EDMUND CRISPIN

The Moving Toyshop

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by

Victor Gollancz 1946

Copyright © Rights Limited,

1946. All rights reserved

Edmund Crispin has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover image © Shutterstock.com

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008124120

Ebook Edition © June 2015 ISBN: 9780008124137

Version: 2017-10-27

For Philip Larkin in friendship and esteem

Contents

Cover (#u54ff471e-8413-58c9-8b49-61b8a4492188)

Title Page (#u6b84451b-d3d9-52db-a980-ca6065490890)

Copyright (#u66a5ea29-f77a-51ac-a165-f2360014c548)

Dedication (#u78686cfa-4cd0-5989-a780-3efd2834e33f)

Note (#ud47e8833-e827-56a4-a856-7645d62adabc)

Map (#u5e7a5487-2dab-528c-9e09-45fb45252911)

Chapter 1: The Episode of the Prowling Poet (#u725fbdc2-b7cb-59da-9242-bc0e27f48dd0)

Chapter 2: The Episode of the Dubious Don (#u24af4404-9f46-5e70-84cd-5e6e5337c7d9)

Chapter 3: The Episode of the Candid Solicitor (#ua4880796-600d-513b-aac7-0f9fd394039e)

Chapter 4: The Episode of the Indignant Janeite (#ud819081f-370a-5f53-a826-9c334fe86a39)

Chapter 5: The Episode of the Immaterial Witness (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6: The Episode of the Worthy Carman (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7: The Episode of the Nice Young Lady (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8: The Episode of the Eccentric Millionairess (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9: The Episode of the Malevolent Medium (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10: The Episode of the Interrupted Seminar (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11: The Episode of the Neurotic Physician (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12: The Episode of the Missing Link (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13: The Episode of the Rotating Professor (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14: The Episode of the Prescient Satirist (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also in This Series (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

Note (#u6c4ce3a2-0ccc-5d2d-9eab-0d47445ddb38)

None but the most blindly credulous will imagine the characters and events in this story to be anything but fictitious. It is true that the ancient and noble city of Oxford is, of all the towns of England, the likeliest progenitor of unlikely events and persons. But there are limits

E.C.

Key

A. Toyshop (second position)

B. St Christopher’s

C. St John’s

D. Balliol

E. Trinity

F. Lennox’s

G. The Mace and Sceptre

H. Sheldonian

I. Rosseter’s office

J. Market

K. Police Station

L. Toyshop (first position)

1 (#u6c4ce3a2-0ccc-5d2d-9eab-0d47445ddb38)

The Episode of the Prowling Poet (#u6c4ce3a2-0ccc-5d2d-9eab-0d47445ddb38)

Richard Cadogan raised his revolver, took careful aim and pulled the trigger. The explosion rent the small garden and, like the widening circles which surrounded a pebble dropped into the water, created alarms and disturbances of diminishing intensity throughout the suburb of St John’s Wood. From the sooty trees, their leaves brown and gold in the autumn sunlight, rose flights of startled birds. In the distance a dog began to howl. Richard Cadogan went up to the target and inspected it in a dispirited sort of way. It bore no mark of any kind.

‘I missed it,’ he said thoughtfully. ‘Extraordinary.’

Mr Spode, of Spode, Nutling, and Orlick, publishers of high-class literature, jingled the money in his trousers pocket – presumably to gain attention. ‘Five per cent on the first thousand,’ he remarked. ‘Seven and a half on the second thousand. We shan’t sell more than that. No advance.’ He coughed uncertainly.

Cadogan returned to his former position, inspecting the revolver with a slight frown. ‘One shouldn’t aim them, of course,’ he said. ‘One should fire them from the hip.’ He was lean, with sharp features, supercilious eyebrows, and hard dark eyes. This Calvinistic appearance belied him, for he was a matter of fact a friendly, unexacting, romantic person.

‘That will suit you, I suppose?’ Mr Spode continued. ‘It’s the usual thing.’ Again he gave his nervous little cough. Mr Spode hated talking about money.

Bent double, Cadogan was reading from a book which lay on the dry, scrubby grass at his feet. ‘“In all pistol shooting,”’ he enunciated, ‘“the shooter looks at the object aimed at and not at the pistol.” No. I want an advance. Fifty pounds at least.’

‘Why have you developed this mania for pistols?’

Cadogan straightened up with a faint sigh. He felt every month of his thirty-seven years. ‘Look,’ he said. ‘It will be better if we both talk about the same subject at the same time. This isn’t a Chekhov play. Besides, you’re being evasive. I asked for an advance on the book – fifty pounds.’

‘Nutling…Orlick…’ Mr Spode gestured uncomfortably.

‘Both Nutling and Orlick are quite legendary and fabulous.’ Richard Cadogan was firm. ‘They’re scapegoats you’ve invented to take the blame for your own meanness and philistinism. Here am I, by common consent one of the three most eminent of living poets, with three books written about me (all terrible, but never mind that), lengthily eulogized in all accounts of twentieth-century literature…’

‘Yes, yes.’ Mr Spode held up his hand, like one trying to stop a bus. ‘Of course, you’re very well known indeed. Yes.’ He coughed nervously. ‘But unhappily that doesn’t mean that many people buy your books. The public is quite uncultured, and the firm isn’t so rich that we can afford—’

‘I’m going on a holiday, and I need money.’ Cadogan waved away a mosquito which was circling round his head.

‘Yes, of course. But surely…some more dance lyrics?’

‘Let me inform you, my dear Erwin’ – here Cadogan tapped his publisher monitorily on the chest – ‘that I’ve been held up for two months over a dance lyric because I can’t think of a rhyme for “British”…’

‘“Skittish,”’ suggested Mr Spode feebly.

Cadogan gazed at him contemptuously. ‘Besides which,’ he pursued. ‘I am sick and tired of earning my living from dance lyrics. I may have an aged publisher to support’ – he tapped Mr Spode again on the chest – ‘but there are limits.’

Mr Spode wiped his face with a handkerchief. His profile was almost a pure semicircle – the brow high, and receding towards his bald head, the nose curving inward in a hook, and the chin nestling back, weak and pitiful, into his neck.

‘Perhaps,’ he ventured, ‘twenty-five pounds…?’

‘Twenty-five pounds! Twenty-five pounds!’ Cadogan waggled his revolver menacingly. ‘How can I have a holiday on twenty-five pounds? I’m getting stale, my good Erwin. I’m sick to death of St John’s Wood. I have no fresh ideas. I need a change of scene – new people, excitement adventures. Like the later Wordsworth. I’m living on my spiritual capital.’

‘The later Wordsworth.’ Mr Spode giggled, and then, suspecting he had committed an impropriety, fell abruptly silent.

But Cadogan pursued his homiletic regardless. ‘I crave, in fact, for romance. That is why I’m learning to shoot with a revolver. That is also why I shall probably shoot you with it, if you don’t give me fifty pounds.’ Mr Spode stepped back alarmedly. ‘I’m becoming a vegetable. I’m growing old before my time. The gods themselves grew old, when Freia was snatched from tending the golden apples. You, my dear Erwin, should be financing a luxurious holiday for me, instead of quibbling in this paltry fashion over fifty pounds.’

‘Perhaps you’d like to stay with me for a few days at Caxton’s Folly?’

‘Can you give me adventure, excitement, lovely women?’

‘These picaresque fancies,’ said Mr Spode. ‘Of course, there’s my wife…’ He would not have been wholly unwilling to sacrifice his wife to the regeneration of an eminent poet, or, for the matter of that, to anyone for any reason. Elsie could be very trying at times. ‘Then,’ he proceeded hopefully, ‘there’s this American lecture tour…’

‘I’ve told you, Erwin, that that must not be mentioned again. I can’t lecture, in any case.’ Cadogan began to stride up and down the lawn. Mr Spode noticed sadly that a small bald patch was beginning to show in his close-cropped, dark hair. ‘I have no wish to lecture. I decline to lecture. It’s not America I want; it’s Poictesme or Logres. I repeat – I am getting old and stale. I act with calculation. I take heed for the morrow. This morning I caught myself paying a bill as soon as it came in. This must all be stopped. In another age I should have devoured the living hearts of children to bring back my lost youth. As it is’ – he stopped by Mr Spode and slapped him on the back with such enthusiasm that the unfortunate man nearly fell over – ‘I shall go to Oxford.’

‘Oxford. Ah.’ Mr Spode recovered himself. He was glad of this temporary reprieve from the embarrassing claims of business. ‘A very good idea. I sometimes regret moving my business into Town, even after a year. One can’t have lived there as long as I did without feeling occasionally homesick.’ Complacently he patted the rather doggy petunia waistcoat which corseted his plump little form, as though this sentiment somehow redounded to his own credit.

‘And well you may be.’ Cadogan wrinkled his patrician features into a grimace of great severity. ‘Oxford, flower of cities all. Or was that London? It doesn’t matter, anyway.’

Mr Spode scratched the tip of his nose dubiously.

‘Oxford,’ Cadogan went on rhapsodically, ‘city of dream-spires, cuckoo-echoing, bell-swarmed (to the point of distraction), charmed with larks, racked with rooks, and rounded with rivers. Have you ever thought how much of Hopkins’s genius consisted of putting things in the wrong order? Oxford – nursery of blooming youth. No, that was Cambridge, but it makes no odds. Of course’ – Cadogan waved his revolver didactically beneath Mr Spode’s horrified eyes – ‘I hated it when I was up there as an undergraduate: I found it mean, childish, petty, and immature. But I shall forget all that. I shall return with an eyeful of retrospective dampness and a mouth sentimentally agape. For all of which’ – his tone became accusing – ‘I shall need money.’ Mr Spode’s heart sank. ‘Fifty pounds.’

Mr Spode coughed. ‘I really don’t think…’

‘Nag Nutling. Oust Orlick,’ said Cadogan with enthusiasm. He seized Mr Spode by the arm. ‘We’ll go inside and talk it over with a drink to steady our nerves. God, I will pack, and take a train, and get me to Oxford once again…’

They talked it over. Mr Spode was rather susceptible to alcohol, and he loathed arguing about money. When at last he went away, the counterfoil of his cheque-book showed the sum of fifty pounds, payee Richard Cadogan Esquire. So the poet got the better of that affair, as anyone not wholly blinded by prejudice would have expected.

When his publisher had departed, Cadogan piled some things into a case, issued peremptory instructions to his servant, and set out for Oxford without delay, despite the fact that it was already half past eight in the evening. Since he could not afford to keep a car, he travelled on the Tube to Paddington, and there, after consuming several pints of beer in the bar, boarded an Oxford-bound train.

It was not a fast train, but he did not mind. He was happy in the fact that for a while he was escaping the worrying and loathsome incursion of middle-age, the dullness of his life in St John’s Wood, the boredom of literary parties, the inane chatter of acquaintances. Despite his literary fame, he had led a lonely and, it sometimes seemed to him, inhuman existence. Of course, he was not sanguine enough to believe, in his heart of hearts, that this holiday, its pleasures and vexations, would be unlike any other he had ever had. But he was pleased to find that he was not so far gone in wisdom and disillusion as to be wholly immune to the sweet lures of change and novelty. Fand still beckoned to him from the white combs of the ocean; beyond the distant mountains there still lay the rose-beds of the Hesperides, and the flower-maidens singing in Klingor’s enchanted garden. So he laughed cheerfully to himself, at which his travelling companions regarded him warily, and, when the compartment emptied, sang and conducted imaginary orchestras.

At Didcot a porter walked down beside the train, shouting, ‘All change!’ So he got out. It was now nearly midnight, but there was a pale moon with a few ragged clouds drifting over it. After some inquiry he learned that there would be a connection for Oxford shortly. A few other passengers were held up in the same way as himself. They tramped up and down the platform, talking in low voices, as though they were in a church, or huddled in the wooden seats. Cadogan sat on a pile of mail-bags until a porter came and turned him off. The night was warm and very quiet.