Полная версия:

A Woman’s Fortune

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Josephine Cox 2018

Jacket design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Jacket photographs © Sandra Cunningham /Arcangel Images (background),

Magdalena Russocka /Trevillion Images (woman), Shutterstock.com (sky)

Josephine Cox asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008128234

Ebook Edition © June 2018 ISBN: 9780008128586

Version: 2018-09-21

Dedication

For my Ken – as always

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

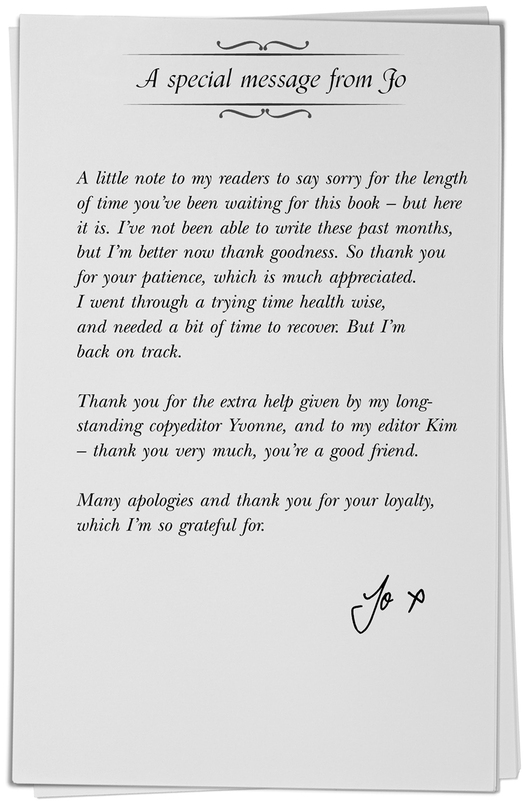

Author Note

Part One: The Leaving

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Part Two: A Turn in the Road

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Epilogue

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Josephine Cox

About the Publisher

PART ONE

The Leaving

July 1954

CHAPTER ONE

Shenty Street, Bolton, Lancashire

She’d seen him around here only a couple of times before, a scruffy-looking man with his cap pulled low and his collar raised high. He had a furtive air, not looking directly at anyone in the street and skulking in the shadows instead of greeting folk with a cheery ‘All right?’ in the usual way. Round here, everyone knew everyone else – and their business – so Evie was certain this man was a stranger. And, from his manner, he was up to no good.

The question was, what did he want with her dad?

She’d now come into the kitchen to make sure her brothers, Peter and Robert, were getting on with their homework, leaving her mum and Grandma Sue folding the dried clothes ready to be ironed. Now, standing just inside, the back door partly closed to conceal her, Evie watched her father and the stranger. The two men faced each other in the shadowy alleyway between the Carters’ house and the next row of terraces. Evie could plainly see both men in profile, her father taller, younger and more handsome than the weaselly-looking fella. The stranger was saying something in a voice too low for her to hear and then Dad, who had been smiling, no doubt laying on the charm, muttered something in return and began to look less happy. The next moment the man, his expression aggressive, was wagging a finger in Dad’s face. Evie was surprised to see her father’s shoulders slump and he no longer met the other man’s eye. She was half ashamed to be snooping and half afraid that here was bad news on the way and she ought to see if she could do something about it before her mum heard. This wouldn’t be the first time Dad had got in a bit of a tight corner, and Mum had lost a bit of her sparkle of late.

Since Evie had left school to help her mother and Grandmother Sue with the washing business she was more aware of what everyone in the family was up to. It wasn’t always bad news with Dad, but there had been some weeks when money was especially tight after he’d had a long evening at the pub, celebrating or commiserating some event with ‘the lads’, especially if the bookie’s runner had been there collecting the stake on some nag that Dad had been told was ‘a certainty’ to win and make his fortune, and which had eventually cantered in well down the field.

Michael Carter was never down for long and, with his irrepressible high spirits, would shrug off his setbacks and carry on regardless, sweeping aside any difficulties as if they weren’t happening. But Mum was sometimes impatient with him these days, and the older she got the more Evie could see Mum’s point of view. Somehow Dad’s jokes weren’t as funny as they used to be, and Evie understood why her mother was beginning to look worn down and her smile had grown, like herself, thin. You couldn’t live on laughs, after all.

What was that word Mary had used when Evie had once confided how annoying Dad’s charm could be when you recognised how he worked it on you? Exasperating. Mary Sullivan, Evie’s best friend, was clever. She always had her head in a book and knew a whole dictionary of good words. She even had a dictionary, so Evie reckoned ‘exasperating’ was probably exactly the right word for her father.

Evie glanced to where her brothers were labouring over their schoolwork at the kitchen table. Their heads were down in concentration so she risked opening the door a fraction wider and craned her neck through the gap. The two men were talking intently but their voices remained low. Then the stranger, with another jab of his pointed finger, turned and disappeared from view. Evie waited a minute, then made a show of opening the back door wide and treading heavily up the alleyway to greet her father where he had moved to stand in the open in front of the house. The summer’s evening sun was low between the rows of back-to-back houses and for a moment a golden beam shone through the sooty air directly onto his face, showing his furrowed brow and his tired eyes with a fine trace of lines she had never noticed before. He was standing with his hands in his pockets, facing into the sun with his eyes closed, almost as if he were praying. Suddenly Evie saw that her handsome dad looked older than his years.

Michael Carter looked up at his daughter’s approach and turned to her, his smile instantly back in place.

‘You all right, Evie?’

‘Just taking a rest before I tackle a pile of ironing. Grandma’s got a bit of mending to do so I said I’d iron. She’s really feeling the heat today.’

‘Well, your gran’s got her own insulation,’ he said, winking. ‘It’s certainly hot work for a July evening.’

‘It is that. But Gran will be taking the good stuff back early tomorrow, so we need to get on.’

‘Oh, leave it, lass. Don’t be beating yourself up. It’ll wait for you.’

‘That’s what I’m afraid of, Dad. There’ll be more tomorrow and I’ll not have Mum or Gran doing my share. Gran’s complaining about her feet, and I don’t blame her. She’s been on them since seven this morning.’

‘She’s a tough old bird, and a good ’un. Don’t tell her I said so, mind.’

Evie and her father exchanged smiles.

Michael called across to Marie Sullivan, who lived in the house opposite and was sweeping dust off her doorstep. ‘All right, Marie? Tell Brendan I’ll see him for a drink later.’

‘I’ll tell him.’

He waved to old Mrs Marsh, who lived next door to the Sullivans, and who was out rubbing Brasso onto her doorknocker. Mrs Marsh was known to be house-proud. ‘Evening, Dora. That’s looking good. I’ll find you a job at ours, if you like.’

‘Give over with your cheek, Michael Carter,’ she grinned.

Evie laughed along with her father. This street was home. She knew no other, and nor did she want to. But the question remained, who was that man with the creeping manner who had caused her father’s smile to slip? She took a breath and decided to plunge in.

‘Dad … who was that man?’

‘What man?’

‘Here, a few minutes ago. In the ginnel.’

‘Here, you say?’

‘Ah, come on, Dad. Talking to you. Just now.’

‘Oh, that man …’

‘Yes, that man. I don’t think he lives round here. Is he a friend of yours?’

‘Well, I wouldn’t exactly call him a friend, love …’

‘What then?’

‘What?’

‘Oh, for goodness’ sake, Dad, do you have to be so exasperating? Who is he and what does he want, lurking round here? Is everything all right? Only you didn’t look too pleased and it set me wondering.’

Michael turned the full beam of his smile on Evie, but she noticed that it didn’t quite reach his eyes. ‘It’s a bit of business, that’s all, love. Nothing for you to worry about.’

Evie fixed him with a hard stare. ‘If you’re sure, Dad,’ she said doubtfully.

‘As I say, sweetheart, nothing to bother yourself over. Or your mum.’ He looked at her meaningfully until she nodded. ‘Now why don’t you go and look in the pantry where I think you’ll mebbe find a bottle or two of cold tea cooling in a bucket on the slab. That’ll help that ironing along, d’you reckon?’

Evie knew there was no point pursuing the matter of the stranger so she shrugged off her anxiety as Michael took her arm with exaggerated gallantry.

‘C’mon, let’s see if the boys have abandoned their homework yet. Your cold tea and ironing await, your ladyship,’ he grinned.

‘Too kind, your lordship,’ Evie beamed, and, their noses in the air in a pantomime of the gentry, they spurned the alleyway and the back door, and let themselves in through the front, laughing.

‘I don’t know what you two have got to be so cheerful about,’ Grandma Sue said, easing a swollen foot out of a worn and misshapen slipper. ‘My ankles are plumped up like cushions in this weather. It’s that airless I can hardly catch my breath.’ She slumped down on one of the spindle-back kitchen chairs and began to massage her foot.

‘Here you are, Gran, a cup of cold tea,’ said Evie, emerging from the pantry and putting Gran’s precious bone-china cup and saucer down on the kitchen table beside her. Sue had been given the china as a present when she left her job as a lady’s maid to get married. No one else in the family would even think of borrowing it, knowing that the crockery was doubly precious to Sue because it had not only survived the war, it had outlasted Granddad Albert, too.

‘Here you are, Mum … boys.’ Evie placed mugs of the tea, which was no longer particularly cold, in front of her mother, Jeanie, and her younger brothers. Peter and Robert were frowning over their school homework, applying themselves to it with much effort and ill grace.

‘Thanks, Sis,’ Peter smiled on her. ‘I’ll just get this down me and then I’m off out to play football with Paddy.’

‘Football, in this heat?’ Sue shook her head and smiled. ‘You’re a tough one, an’ no mistake.’

‘Lazy one, more like,’ said Jeanie, taking off her pinny. ‘What have I said about not going out to play until you’ve done your homework?’ She sat easing her back, then removed the turban she wore when she was working to try to prevent the steam from the copper frizzing her hair. As her mother raised her arms and pushed up her flattened curls, Evie noticed how sore her hands were. Mum liked to look nice but it was difficult in this heat, with all the steam and hard work. In winter it was even worse, though.

‘It’s too hot to do schoolwork. It’s the play next week and no one’s bothered about doing sums when there’s the play to rehearse.’

‘But you’re not even in the play, are you, Pete? Isn’t it just the little ’uns that are doing the acting?’

‘I’m in the choir and I’m playing the whistle,’ said Peter. ‘You can’t have a play without music.’

‘That’s right,’ Robert had his say as always. ‘Pete’s got a solo.’

‘Two solos,’ Peter corrected. ‘Anyway, it’s only one more year before I’m fourteen and then I can leave school. I can read and write already – what more do I need when I’m going to be a musician?’

‘A musician, is it now?’ smiled Sue. ‘I don’t know where you get such fancy ideas.’

‘Fifteen,’ Michael corrected, coming out of the pantry with a second bottle of cold tea. ‘You can’t leave until you’re fifteen.’

‘But that’s not fair. Evie left at fourteen. Why can’t I?’

‘Evie left to help Mum and Grandma Sue with the washing,’ Michael reminded his elder son, not for the first time. ‘The authorities turn a blind eye if you’ve got a family business to go into, especially when it’s the best in Bolton.’ He beamed at Jeanie and she rolled her eyes at his nonsense.

‘And if I don’t get on with that last pile of ironing I might as well have stayed at school,’ Evie said, getting up and moving to the ironing board, beside which was a pile of pretty but rather worn blouses.

‘I could always go and help you at the brewery until the music takes off, Dad,’ Peter went on, adding innocently, ‘I’m sure we need the money.’

‘And you wouldn’t be spending it in the pub like Dad does either,’ Robert said, unwisely. ‘Or betting on horses.’

Typical, thought Evie, in the brief silence that followed. When would Robert ever learn to keep quiet?

Jeanie, Sue and Michael all spoke at once.

‘Shut up, Bob, and get on with your homework. I won’t have you cheeking your father,’ said Jeanie.

‘I think you’re asking for a clip round the ear, my lad,’ said Sue.

‘Ah, come on, son. A man’s got a right to have some fun,’ said Michael.

Robert lowered his head and began snivelling over his exercise book while Peter got up very quietly, collected his books into a neat pile and sidled over to the door.

‘I’ll see you later,’ he muttered and left, taking his mug of tea with him.

Sue eased herself off the chair and made for the living room, where the light was better and where she kept her workbasket. ‘I’ll just finish that cuff on Mrs Russell’s blouse and you can add it to the pile. I’m that grateful for your help this evening.’

‘Oh, and I’ve found one with a missing button. Do you have a match for this?’ Evie followed her grandmother through with a spotlessly white cotton blouse and showed her where the repair was needed.

Sue turned to her button box and Evie went back to the ironing, mussing up Robert’s fair hair supportively as she passed. Robert was still sniffing over his schoolbooks, writing slowly with a blunt pencil. The distant sound of Peter’s voice drifted up the alleyway from the street, Paddy Sullivan answering, and then the dull thud of a football bouncing.

‘Right,’ said Michael, ‘I’ll be off out. See you later, love.’ He planted a kiss on the top of Jeanie’s head and was gone. Jeanie didn’t need any explanation.

She got up and took her tea into the living room to sit with her mother.

‘Let’s hope he comes back sober,’ Sue muttered under her breath.

‘He’s usually better on a weekday,’ Jeanie said loyally, ‘and it’s Thursday as well, so I reckon there isn’t much left to spend anyway.’

They each lapsed into silence with a sigh.

Evie shared the attic bedroom with her grandma. It was hot as hell that night, as if all the heat from the street and the scullery and the kitchen had wafted up into the room and lingered there still. It was dark outside, although the moon was bright in the clear sky. Sue was lying on her back on top of her bed, her head propped up high on a pillow and with the bedclothes folded neatly on the floor at its foot. She was snoring loudly. Evie thought she looked like an island – like a vast landmass such as she’d seen in the school atlas – and Sue’s swollen feet, which Evie could just see in the dark, looked enormous, being both long and very wide. Poor Gran, thought Evie, it must be a trial carrying all that weight on your bones in this weather.

It was Sue’s snoring that had woken Evie and now she was wide awake and too hot to get back to sleep. The bed seemed to be gaining heat as she lay there and the rucked-up sheet was creased and scratchy. Lying awake and uncomfortable, Evie thought of the weaselly stranger she had seen earlier, how Dad had swerved her questions and obviously didn’t want her to know anything about the man. He’d more or less admitted it was a secret from Mum, too, and therefore from Grandma.

I bet it’s about money, Evie thought.

Her dad had a job at the brewery loading drays and doing general maintenance. She had long ago realised that it wasn’t very well paid. Despite Jeanie’s scrimping and all the doing without, though, Dad didn’t seem to care. He just carried on going for a drink or three, and enjoying what he called ‘a little flutter’ on the dogs or the horses. ‘You have to place the bet to have the dream of winning,’ he had explained to Evie. ‘A few pounds is the price of the dream.’ Sometimes he did win. Mostly he didn’t.

The laundry helped to support them. For someone so old – she was sixty-three and didn’t care who knew it – Grandma Sue was full of go, always trying to think of ways to improve the little business. She offered mending and alterations, and had found new customers away from the immediate neighbourhood – people with a bit more to spend on the extra service.

Enterprise, Mary Sullivan had called it. ‘Everyone admires your gran,’ Mary had said. ‘She doesn’t sit around being old, she gets on with it.’ Evie had to agree that Grandma Sue was amazing.

Evie looked at her now, lying on her back, snoring like billy-o, and grinned.

Getting up silently, Evie went to stand in front of the open sash window, desperate for a breath of cool fresh air. The rooftops of the houses opposite were visible but, from where she stood, there was no one in sight in the street. She lingered, breathing deeply of the hot, sooty air, leaning out and turning her head to try to catch any breeze.

Then she heard the echoing sound of approaching uneven footsteps and recognised her father coming down the street, weaving slightly, not hurrying at all, although it must be very late as he was the only person in sight. But – no, there was another man. Evie hadn’t heard him, but suddenly the man was right there, outside the house. She leaned out further to see who had waylaid her father; it was the man she’d seen earlier. In the quiet of the night their voices drifted up to her, and her heart sank. Something was not right.

‘I told Mr Hopkins what you said and he isn’t prepared to wait that long,’ growled the stranger. ‘He wants his money now.’

‘And I told you I don’t have it,’ Michael said. ‘I’ll pay him what I owe, I promise, but I need more time.’

‘Mr Hopkins says you’ve had long enough. He’ll be charging the usual rates from now.’

‘Please, I can get it all by next month. I just need a bit longer to get sorted, that’s all.’

‘I’ll be sorting you out if Mr Hopkins doesn’t see his money soon,’ snarled the man, leaning in close. Evie felt hot all over, the beginnings of panic flipping her stomach.

‘Next week, then,’ she heard her father pleading. ‘I’ll get it by the end of next week. C’mon now, I can’t say fairer than that.’ He tried for a friendly tone, a man-to-man kind of banter, but Mr Hopkins’ man was not to be charmed from his purpose.

‘Next week it is, then,’ he said, ‘but there’ll be interest, too, don’t forget. You should have paid up straight away, Carter. It’s going to cost you more now. I’ll be back to collect what you owe. All of it, and the interest. And if you don’t pay – and I mean every pound of the debt – I wouldn’t want to be in your shoes. You won’t be able to talk your way out of it with Mr Hopkins. Let this be fair warning to you.’ It was a dark warning.

The stranger seemed to melt away in the darkness, and Evie slowly sank down to the floor beside the window. She had a sense of trouble. Oh dear God, every pound. Dad owed Mr Hopkins pounds! And he had only until the end of next week to pay. And tomorrow was Friday already. How on earth had Dad got himself into that kind of mess? It couldn’t be a bad bet on the horses. That might have wiped out his wages but wouldn’t have led to such a debt, surely. Maybe this Mr Hopkins was a moneylender. Oh good grief, this was serious …

She sat numbly thinking about pounds of debt for a while, then got up stiffly and crept back to bed. Sue’s snoring had subsided, thank heaven, and she was blissfully asleep. Evie lay down and tried to work through the situation in her head. Who else knew? No one, she guessed.

Evie wished that she didn’t know, and her father’s secret was so terrible that she couldn’t unburden herself by sharing it with anyone, especially when her mum and grandma were so tired after working all hours doing laundry. She didn’t want to worry them until she knew what was going on and how bad things were. First she’d have to confront Dad and see what he had to say, though she didn’t hold out much hope of getting a straight answer. She’d already tried asking about the stranger and he’d pretended there wasn’t anything wrong. No doubt he’d try to fob her off with some tale when she questioned him about what she’d overheard …

It didn’t occur to her to leave the matter to her father to deal with alone. Now the truth was out she couldn’t sweep it under the rug and forget what she knew. That was the kind of thing he did, and look where it had got him. He needed to face facts and do something about the trouble he was in. That awful man had sounded dangerous.