Полная версия:

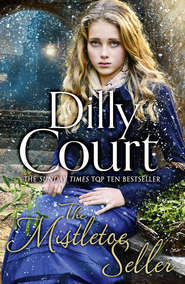

The Mistletoe Seller: A heartwarming, romantic novel for Christmas from the Sunday Times bestseller

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Dilly Court 2017

Cover photographs © Gordon Crabb/Alison Eldred (Girl); Shutterstock (background)

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Dilly Court asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008199555

Ebook Edition © November 2017 ISBN: 9780008199579

Version: 2017-08-09

Dedication

In loving memory of Harry House

2013–2016

Taken too soon but never forgotten

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Dilly Court

About the Publisher

Chapter One

St Mary Matfelon Church, Whitechapel, London – Christmas Eve 1859

‘I found her in Angel Alley, Vicar.’ The verger cradled the infant in his arms, protecting her from the falling snow. ‘She was all alone and no one else in sight.’

‘Bring her into the warmth, Fowler, before she freezes to death.’ The Reverend John Hardisty stood aside, ushering the verger into the candlelit church. The bells were ringing out to summon worshippers to midnight mass, and the first of the faithful were already starting to arrive.

‘What will we do with her, Vicar?’ Jim Fowler gazed down into the blue eyes that regarded him with an unblinking stare. ‘She must be cold and no doubt she’ll be hungry soon. Where will we find someone to care for her at this time of night, and at Christmas, too?’

‘Take her to the vestry. My wife will know what to do.’

A married man himself, with nine little Fowlers to raise, Jim carried the infant to the vestry and as he pushed the door open he was greeted by the sound of female chatter, which stopped abruptly when the assembled ladies spotted the baby.

‘Good gracious, Jim, what have you got there?’ Letitia Hardisty surged towards him, peering at the baby with undisguised distaste. ‘Not another foundling, surely?’

‘Oh, Letty, that’s not a very Christian attitude.’ Cordelia Wilding, a plump woman wearing a fur-trimmed velvet bonnet and matching cape pushed past her to snatch the infant from the verger’s arms. ‘What a beautiful child. Just look at those soft golden curls and big blue eyes. She’s a little angel.’

The third woman, Margaret Edwards, the deacon’s wife, plainly dressed in serviceable grey linsey-woolsey with an equally plain bonnet, leaned over to take a closer look at the baby. ‘A Christmas angel, to be sure. I believe she’s smiling, Cordelia.’

‘It’s probably wind.’ Letitia stood back, frowning thoughtfully. ‘If you’ll stop cooing over her, ladies, you’ll realise that we have a problem on our hands.’

Margaret touched the infant’s cheek with the tip of her finger. ‘Where did you find her, Fowler? Was there a note of any kind?’

Jim puffed out his chest, pleased to be able to tell the deacon’s wife something she did not know. Margaret Edwards was notoriously opinionated and very conscious of her husband’s standing in the community. ‘I took it to be of the female gender, ma’am. Judging by the lace dress, which must have cost a pretty penny, in my humble opinion.’ He glanced round the small group and he realised that they were unimpressed. He cleared his throat. ‘Ahem … I was taking a short cut through Angel Alley and I heard a sound. She weren’t crying, but sort of cooing, as if to call out to me.’

‘Very interesting,’ Letitia said sharply. ‘But was she on a doorstep? If so, the mother might have intended the householder to take her in. Or was she in some sort of shelter? It’s been snowing for several hours.’

Cowed by her supercilious stare and the caustic tone of her voice, he bowed his head. ‘She was left in a portmanteau, ma’am.’

‘A portmanteau?’ Margaret tapped her teeth with her fingernail, a habit that never failed to annoy Letitia.

‘I think we all know what a portmanteau is, Margaret.’ Letitia moved closer to the verger, fixing him a stern look. ‘Did you bring it with you? It might help us to identify the child. This is obviously a matter for the police.’

He shook his head. ‘It were sodden with snow, ma’am. I was too concerned about the little one to think of anything but getting her to safety.’

‘You stupid man. There might have been a clue as to who she is, if indeed it is a girl.’ Letitia cocked her head, listening. ‘The bells have stopped. It’s time for the service to begin. We can’t stay here talking all night.’

‘What will we do with the infant, Letty?’ Cordelia clasped her hands to her bosom, her grey eyes filling with tears. ‘Someone must take her in. I would, but I’m afraid Mr Wilding would object. We have visitors staying with us, important business contacts, you understand.’

‘I can’t have her,’ Margaret said firmly. ‘I must support the deacon during this busy time of the year. He has his duties to perform, as has the vicar.’

‘And for that reason I cannot have her either,’ Letitia added, nodding. ‘Besides which, the child needs a wet nurse.’ She turned to Jim. ‘You have a large family, Fowler. Surely one more would make little difference, and I seem to remember that your youngest is only a few months old.’

Jim took a step backwards, holding up his hands. ‘My Florrie has enough to do, ma’am. We can barely feed and clothe the young ’uns as it is. Maybe the Foundling Hospital would take her in, or else it will be the workhouse.’

‘Send for a constable,’ Letitia said hurriedly. ‘The police station in Leman Street is the best place for the child. They’re used to handling such matters, and you, Fowler, must go to Angel Alley right away and fetch the case in which you found the baby. It might prove to be vital evidence for the police to find and apprehend the mother who committed the crime of abandonment.’

‘Oh, no, Letty,’ Cordelia said tearfully. ‘The poor creature needs sympathy. Where is your compassion? It is Christmas Eve, after all. Remember the babe that was born in the stable.’

‘The stable in Bethlehem is not Angel Alley in Whitechapel, Cordelia.’ Letitia shooed the verger out of the room. ‘You had best stay with the child, Cordelia, since she seems to be taken with you. Come, Margaret, the service has started.’ She left the vestry with the deacon’s wife following in her wake.

Cordelia sank down on one of the upright wooden chairs – comfort was not the main purpose of the vestry furniture. She unfolded the woollen shawl, which was new and of the best quality. The flannel nightdress was trimmed with lace and the yoke embroidered with tiny pink rosebuds. Someone, perhaps the expectant mother, had put time and effort into making the garment. Cordelia was not the most imaginative of people, but it seemed unlikely that someone who had taken such trouble over a simple nightgown would desert a much-wanted infant. The baby had not uttered a sound, and that in itself was unnerving and seemed unnatural. Cordelia had long ago given up hope of having a child of her own, and although part of her longed to take the little one home and give her the love and attention she deserved, a small voice in her head warned her against such folly. Her husband, Joseph Willard Wilding, was a successful businessman who had bought a failing brewery and turned its fortune around. They entertained regularly and she was expected to be the perfect hostess. A child would not fit in with their way of life.

‘You are a beautiful little girl. If you were mine I would christen you Angel, because that’s what you are.’

The baby gurgled and a tiny hand grasped Cordelia’s finger with surprising strength. She felt a tug at her heartstrings and an ache in her empty womb.

How long Cordelia sat there she did not know, but she felt a bond growing with the child and the sweet, milky, baby smell filled her with unacknowledged longing. Then, just as Angel was becoming restive and beginning to whimper, the door burst open and Jim entered, carrying a large portmanteau. He was followed by a police constable. The last words of ‘Come All Ye Faithful’ echoed around the vestry as the policeman closed the door.

‘This is the infant, Constable Miller,’ Jim said importantly. ‘The one I found in Angel Alley, lying in this here case as if she was a piece of left luggage. I don’t know what the world is coming to.’

Constable Miller took the portmanteau from him and proceeded to examine it in the light of a candle sconce. ‘There doesn’t seem to be a note of any kind, Mr Fowler.’ He raised his head, giving Cordelia a questioning look. ‘Was there a note pinned to the baby’s shawl, ma’am? The child’s name, maybe?’

Cordelia shook her head. ‘Nothing, Constable. The baby is well cared for and clean, and her garments are of good quality.’

Constable Miller ran his hands around the lining of the case. ‘Aha. As I thought. There is generally something personal to the mother left with foundlings.’ He held up a gold ring set with two heart-shaped rubies. ‘This might be valuable,’ he said thoughtfully, ‘but I’m not an expert in jewellery. Anyway, it might help us to find the mother, or it’s possible she will have second thoughts and return to the place where she abandoned her baby. Women do strange things in such cases.’

‘What will happen to the child now?’ Cordelia asked anxiously. ‘You won’t lock her in a cell overnight, will you?’

A wry smile creased Constable Miller’s face into even deeper lines. ‘I doubt if the other occupants of the lock-up would appreciate a nipper howling its head off, ma’am. I’ll have to report back to the station, but I expect she’ll end up in the workhouse if the Foundling Hospital can’t take her.’

Jim backed towards the door. ‘I’ve got to go, Constable. The service has ended and I’ll be needed to tidy up ready for the Christmas Day services.’ He let himself into the body of the church, closing the door behind him.

‘Busy for all of us,’ Constable Miller said drily. ‘No doubt we’ll be scooping the drunks off the streets and arresting the pros—’ He broke off, his face flushing brick red. ‘I’m sorry, ma’am. I mean we’ll be keeping the streets as free from crime as possible in this part of the East End.’ He reached out to take the baby, but Cordelia tightened her hold on the tiny body.

‘I don’t like to think of Angel in such a place, Constable. Or in the workhouse, if it comes to that.’

‘She has a name, ma’am?’

Cordelia blushed rosily. ‘I’ve been calling her Angel because she was found in Angel Alley and because it’s Christmas, and she looks like an angel.’

‘I don’t suppose you’d like to take care of her for a couple of days, would you, ma’am? It would make my life easier and you obviously have some feelings for the little mite. Which,’ he added hastily, ‘I can understand, being the father of five. I’d take her myself, but for the fact that my wife is sick in bed and the nippers are having to look after themselves.’

‘I wish I could, Constable,’ Cordelia said with genuine regret, ‘but my husband wouldn’t agree, and anyway, she needs a wet nurse.’

‘Give her to me then, ma’am. I’m sure the sergeant at the station will know of some woman who’d like to earn a few pence for her labours.’

Cordelia hesitated. ‘I suppose that means some slattern who might be disease ridden and most certainly of low morals.’

‘That I can’t say, ma’am.’ Constable Miller kept his tone moderate but he was tired and coming to the end of his shift. His only wish was to take the tiresome infant to the station and see it safely settled before he went home to his family, left in the care of his eldest daughter, a child of ten. Whether or not they were asleep in bed was something he would discover when he opened the door of their two-up, two-down terraced house. No doubt they would have searched the cupboards for their presents, such as they were, but all he could afford on a constable’s pay were wooden toys made from offcuts by the carpenter who lived at number six, and rag dolls that his wife had spent many evenings sewing by the light of a single candle.

Cordelia rose to her feet, still clutching Angel, who was growing restive and her whimpering was rapidly growing in volume. ‘I must come with you, Constable. I have to make certain that this child is placed in safe hands.’ Cordelia turned her head as the door opened to admit Letitia, the vicar and Joseph Wilding, and judging by the expressions on their faces she realised that her decision was going to attract strong opposition. She explained hastily, but Joseph barely allowed her to finish speaking.

‘It’s ridiculous, Cordelia. The child has been deserted by her mother and goodness knows where it came from. The thing might be riddled with disease and you have a delicate constitution. Come away and leave the matter to the authorities.’

‘Yes, my dear,’ Letitia said smoothly. ‘Your caring attitude is admirable, but misplaced. There are institutions that care for this type of child.’

‘And what type is that?’ Cordelia demanded angrily. ‘Angel is an innocent, just like the Child whose birth we are supposed to be celebrating at Christmas.’

Shocked, Letitia stared at her wide-eyed. ‘That is blasphemous, Cordelia.’ She turned to her husband. ‘Pretend you didn’t hear that, John. Cordelia is obviously beside herself, and it’s very late. Time we were all tucked up in our beds so that we can be ready for tomorrow – or rather, later on today. Go home, Cordelia, and leave the matter in the hands of the police.’

Cordelia held the child closer as she rose to her feet. Rebellion was not in her nature and she would normally have complied with her husband’s wishes, but this was different. ‘No,’ she said firmly.

‘No?’ Letitia and Joseph spoke in unison.

‘It’s all right, ma’am,’ Constable Miller said hastily. ‘I will make certain that the child is well cared for.’

Cordelia shot a sideways look at her husband. ‘I am not abandoning this infant. I intend to accompany Constable Miller to the police station, and I will stay with Angel until I am satisfied that appropriate arrangements have been made for her care.’

‘Cordelia, I forbid you—’ Joseph broke off mid-sentence. The stubborn set of his wife’s normally soft jawline and the martial gleam in her large grey eyes both startled and confused him. Used as he was to commanding his army of workers at the brewery and generally getting his own way by simple force of his domineering nature, he was suddenly at a loss.

‘I am going with her,’ Cordelia said simply. ‘It’s Christmas Day and my little winter angel needs the comfort of loving arms. I will never know the joy of holding my own child, so please allow me this one small thing, Joseph.’

John Hardisty cleared his throat, touched to the core by the simple request of a childless woman. ‘I will accompany you, my dear Mrs Wilding. If Joseph feels he must tend to your guests then please allow me to be of assistance.’

‘That won’t be necessary, Vicar.’ Joseph moved to his wife’s side. ‘I’m sure my friends will understand. I don’t agree with what you’re doing, Cordelia, but I am prepared to humour you – just this once.’

She met his gaze with a steady look. For the first time in the twenty-five years of their marriage she knew that she was in control, and it was a good feeling. She said nothing as she followed the constable out of the church, wrapping her cape around the baby to protect her from the heavily falling snow.

‘Get into the carriage, Cordelia,’ Joseph said sternly. ‘Might I offer you a lift, Constable?’

‘I’m supposed to be walking my beat, sir.’ Constable Miller squinted up into the swirling mass of feathery snow. ‘But I suppose under the circumstances it would be appropriate.’

The desk sergeant dipped his pen into the inkwell. ‘Name, please?’

‘Cordelia Wilding.’

‘No, ma’am, the infant’s name, if it has one.’

‘Angel,’ Cordelia said firmly.

‘Angel?’ He looked up, frowning. ‘Surname?’

‘Really, Officer, is this necessary?’ Joseph leaned over the desk. ‘My wife knows nothing of this child. She’s simply caring for the infant until someone comes to take her away.’

A shaft of fear stabbed Cordelia with such ferocity that she could scarcely breathe. ‘Angel Winter. It’s the name I’ve given the poor little creature who’s been cruelly abandoned by her mother. She needs someone who can take care of her bodily needs, and a home where she will be loved.’

‘Don’t we all, ma’am?’ Sergeant Wilkes said drily.

‘I suggested the Foundling Hospital, Sergeant,’ Constable Miller took his notebook from his pocket. ‘The infant was found at approximately eleven forty-five in Angel Alley by a Mr James Fowler, the verger at St Mary’s church, and taken into the vestry where this good lady has been taking care of the said babe.’

The sergeant glanced at the clock. ‘It’s nearly half-past one in the morning, and it’s Christmas Day. I doubt if anyone would be happy to be awakened at this time.’

As if acting on cue, Angel began to cry and this time no amount of rocking or soothing words made any difference.

‘She’s hungry,’ Cordelia said apologetically. ‘A wet nurse must be found immediately.’

‘Lumpy Lil is in the cells, Constable Miller. Go and fetch her, if you please. She’s up for soliciting again.’ Sergeant Wilkes shot an apologetic glance in Cordelia’s direction. It was bad enough having a nipper howling its head off fit to bust, without the added complication of there being a lady present. He thought longingly of home and a warm fireside, a pipe of baccy and a glass of porter to finish off a long day. ‘Begging your pardon, ma’am.’

‘Lumpy Lil,’ Cordelia repeated faintly. The image this conjured up made her shudder, but Angel’s cries were becoming more urgent, and she supposed that one mother’s milk was as good as another’s, even if the woman was of questionable morals.

Joseph moved closer to her, lowering his voice. ‘Come away now, Cordelia. You’ve done your best for the infant. Let the police deal with her.’

She turned on him in a fury. ‘You make Angel sound like a criminal. I won’t abandon her, and I intend to remain here until I’m satisfied that a good home has been found for her.’

‘This is ridiculous, my dear,’ Joseph said through clenched teeth. ‘You cannot stay here all night, and possibly all day too. I won’t allow it.’

Cordelia turned away in time to see Constable Miller escorting a large, raw-boned woman along the corridor that presumably led from the cells. Lumpy Lil lived up to her name – her torn blouse was open to the waist, exposing large breasts, purple veined and threatening to burst free from the confines of tightly laced stays.

‘Good grief!’ Joseph stared at her in horror. ‘Surely not this creature.’

‘Where’s the little brat then?’ Lil’s words were slurred. It was obvious that she had been drinking and was still under the influence, but Angel was screaming by this time, and much as Cordelia hated the thought of this unwashed, drunken woman laying hands on her pure little angel, she could see that there was little alternative. She cleared her throat, meeting Lil’s aggressive glare with an attempt at a smile.

‘I know it’s a lot to ask, but would you be kind enough to give sustenance to this poor little child, Miss Lumpy?’

‘It’s Miss Heavitree to you, lady.’ Lil tossed back her shaggy mane of mouse-brown hair. ‘You never told me the queen was visiting Leman Street nick, Constable Miller.’

‘Less of your cheek, Lil. You know what’s required of you.’

‘Give us the kid, missis.’ Lil held her arms out, exposing tattoos that ran from her bony wrists to her elbows. ‘I’ll be glad to get some relief from me sore titties. My babe only lived three days, and then the cops brought me in for trying to make a living.’ She spat on the floor at Constable Miller’s feet, narrowly missing his boots. ‘I provides a valuable service, they knows that.’

‘Less of your lip, Lumpy.’ Constable Miller poked her in the back. ‘If you’re willing to take care of the nipper you can use the inspector’s office. He’s at home with his family, where we all should be, and I’m going off duty, so don’t give me any trouble.’

‘All right, I’ll see to the little thing. What’s her name?’

‘I call her Angel.’

‘There’s no accounting for taste. I dare say she’ll be as much of a brat as the rest of ’em when she’s old enough to answer back.’ Lil flung the baby over her shoulder with careless abandon. ‘Lead on, Constable. You can stay and watch if it gives you pleasure.’ She winked at him, but Constable Miller merely shrugged and gave her a push in the direction of the office.

‘It would be nothing new to me, Lil. I’ve got five of my own, but I’ll be outside the door, so don’t try to escape.’