скачать книгу бесплатно

3 (#ulink_adea76f2-1547-5e1f-9272-bf283c0d17b9)

They talk to each other as if I’m not here, and I continue looking at the video playing on my phone. I continue waiting for something to happen.

I’m more than four minutes into it and can’t pause or save it. Every key I touch, every icon and menu is nonfunctional and the recording rolls on but nothing changes. The only movement I’ve detected so far are the subtle shifts of light from the edges of the closed slatted blinds.

It was a sunny day but there must have been clouds or the light would be steady. It’s as if the dorm room is on a dimmer switch, bright then not as bright. Clouds moving across the sun I deduce as Hyde and the trooper hover near the mahogany staircase, loudly voicing opinions, making comments and gossiping as if they think I’m obtuse or as dead as the woman on the floor.

“If she asks I don’t think we tell her.” Hyde has stayed on the subject of Amanda Gilbert’s anticipated arrival in Boston. “The air being turned off is a detail we want to keep away from her and for sure keep out of the media.”

“It’s the only thing weird about this. You know that gives me a bad feeling.”

It’s certainly not the only thing weird about this, I think but don’t verbalize.

“That’s right and it starts a shit storm of rumors and conspiracy theories that end up all over the Internet.”

“Except sometimes perps turn off the air-conditioning, turn on the heat, do whatever to make a place hot so they can speed up decomp. To disguise the correct time of death so they can create an alibi and screw up evidence, isn’t that true, Doc?” The state trooper with his Massachusetts accent addresses me directly, his r’s sounding like w’s when he’s not coughing.

“Heat escalates decomposition,” I reply without looking up. “Cold slows it down,” I add as I realize what it means that the dorm room walls in the video are eggshell white.

When Lucy first started staying at Washington Dorm the walls in her room were beige. Later they were repainted. I recalculate my timeline. The video was taken in 1996. Maybe 1997.

“Dunkin’s got pretty good breakfast sandwiches. Would you like something to eat, ma’am?” The trooper in his blue and gray is talking to me again, sixtyish with a belly and he doesn’t look well, his face wasted with dark circles under his eyes.

I have no idea what he’s doing at the scene, what useful purpose he might possibly serve. Besides that he sounds quite ill. But it wasn’t up to me who to invite, and I glance down at Chanel Gilbert’s battered dead face, at her bloody nude body with its greenish discoloration and bloating in the abdominal area from bacteria and gases proliferating in her gut due to putrefaction.

The housekeeper told the police she didn’t touch the body or even get close, and I don’t doubt that Chanel Gilbert is exactly as she was found, her black silk bathrobe open, her breasts and genitals exposed. I’ve long since lost the impulse to cover a dead person’s nudity unless the scene is in a public place. I won’t change anything about the position of the body until I’m certain everyone is done with photographs and it’s time to pouch it and transport it to the CFC. That will be soon enough. Very soon as a matter of fact.

I’m sorry, I wish I could say to her as I scan puddles of blood that are a viscous dark red and drying black around the edges. Something urgent has come up. I have to leave but I’ll be back, I’d tell her if I could, and I’m vaguely aware of how loud the flies have gotten inside the foyer. With doors opening and shutting as cops come in and out of the house, flies have invaded, shimmering like drops of gasoline, alighting and crawling, looking for wounds and other orifices to lay their eggs.

My attention snaps back to the display of my phone. The image is the same. Lucy’s empty dorm room as seconds tick by. Two hundred and eighty-nine. Three hundred and ten. Now almost six minutes and there must be something coming. Who sent this to me? Not my niece. There would be no reason on earth. And why would she do it now? Why after so many years? I have a feeling I know the answer. I don’t want it to be true.

Dear God don’t let me be right. But I am. I’d have to be in total denial not to put two and two together.

“They have vegetarian sandwiches if that’s your thing,” one of the cops is saying to me.

“No thanks.” I keep waiting as I watch, and then I sense something else.

Hyde is pointing his phone at me. He’s taking a photograph.

“You’re not going to do something with that,” I say without looking up.

“I thought I’d tweet it after I Facebook it and post it on Instagram. Just kidding. You checking out a movie on your phone?”

I glance up long enough to catch him staring at me. He has that glint in his eyes, the same mischievous gleam he gets when he’s about to spitball another lamebrain quip.

“I don’t blame you for entertaining yourself,” he says. “It’s kinda dead in here.”

“I can’t do that. I’m too old-school,” the trooper says. “I need a decent size screen if I’m watching a movie.”

“My wife reads books on her phone.”

“Me too. But only when I’m driving.”

“Ha-ha. You’re a real comedian, Hyde.”

“Do you think it’s worth stringing in here? Hey Doc?”

I realize another Cambridge cop has appeared. He starts in about how to handle the blood evidence. I don’t know his name. Thinning gray hair, a mustache, short and squat, what they call a fireplug build. He doesn’t work for investigations but I’ve seen him on the Ivy League streets of Cambridge pulling people, writing tickets. One more nonessential who shouldn’t be here but it’s not for me to order cops off the scene. The body and any associated biological evidence are my jurisdiction but nothing else is. Technically.

Yes technically. Because in the main I decide what are my business and my responsibility. It’s rare I get an argument. Overall my working relationship with law enforcement is collaborative and most times they’re more than happy for me to take care of whatever I want. They almost never question me. Or at least they didn’t used to second-guess hardly anything I decided. That might be different now. I might be getting a taste of how things have changed in two short months.

“In this blood spatter class I went to they said you should string everything because you’re going to get asked in court,” the cop with thinning gray hair is saying. “If you testify that you didn’t bother with it? It looks bad to the jury. What they call the list of NO questions. The defense attorney goes through all these questions he’s sure you’ll answer no to, and it makes you look like you didn’t do your job. It makes you look incompetent.”

“Especially if the jurors watch CSI.”

“No shit.”

“What’s wrong with CSI? You don’t got a magic box in that field case of yours?”

This continues and I barely listen. I let them know that stringing would be a waste of time.

“I figured as much. Marino doesn’t see the point,” one of the cops replies.

I’m so glad Marino says it. That must make it true.

“We could bring in the total station if you want. Just reminding you we have that capability,” the trooper says to me, and then he goes on to explain about TSTs, about electronic theodolites with electronic distance meters although he doesn’t use words like that.

I know your capabilities better than you do and have handled more death scenes than you’ll ever dream of.

“Thanks but it’s not necessary,” I answer without so much as a glance at the hieroglyphics of dark bloodstains under and around the body.

I’ve already translated what I’m seeing, and using segments of string or sophisticated surveying instruments to map and connect blood streaks, swipes, sprays, splashes and droplets would offer nothing new. The area of impact is the floor under and around the body plain and simple. Chanel Gilbert wasn’t upright when she received her fatal head injuries plain and simple. She died where she is now plain and simple.

This doesn’t mean there was no foul play, far from it. I haven’t examined her for sexual assault. I haven’t done a 3-D CT scan of her body or autopsied it yet, and I go through my differential about what I’m seeing as I ask what was in her bathroom, on her bedside table.

“I’m interested in any prescription bottles for drugs. Any drugs including medications such as lenalidomide, in other words long-term nonsteroidal therapy that is immunomodulatory,” I explain. “A recent course of antibiotics also could have contributed to bacteria growth, and if it turns out she’s positive for clostridium, for example, that could help explain a rapid onset of decomposition.”

I inform them I’ve had several cases of that due to a gas-producing bacteria like clostridium where literally I saw postmortem artifacts similar to these at only twelve hours. All the while I’m going into this with the police I keep my eyes on the display of my phone.

“You talking about C. diff?” The trooper raises his voice and almost strangles on his next fit of coughing.

“It’s on my list.”

“She wouldn’t have been in the hospital for that?”

“Not necessarily if she had a mild form. Did you see antibiotics, anything back in her bedroom or bathroom that might indicate she was having a problem with diarrhea, with an infection?” I ask them.

“Gee I’m not sure I saw any prescription bottles but I did see weed.”

“What worries me is if she had something contagious,” the gray-haired Cambridge cop offers reluctantly. “I sure as hell don’t want C. diff.”

“Can you catch it from a dead body?”

“I don’t recommend contact with her feces,” I reply.

“It’s a good thing you told me.” Sarcastically.

“Keep protective clothing on. I’ll check for any meds myself and would rather see them in situ anyway. And when you get back from Dunkin’ Donuts?” I add without looking up. “Remember we don’t eat or drink in here.”

“No worries about that.”

“There’s a table in the backyard,” Hyde says. “I thought we could set up a break area out there as long as we do it before the rain comes. We got a couple of hours before the big storm they’re predicting rolls in.”

“And we know nothing happened in the backyard?” I ask him pointedly. “We know that’s not part of the scene and therefore it’s okay for us to eat and drink back there?”

“Come on, Doc. Don’t you think it’s pretty obvious she fell off a ladder here in the foyer and that’s what killed her?”

“I don’t arrive at a scene supposing anything is obvious.” I barely glance up at the three of them.

“Well I think what happened here is obvious to be honest. Of course what killed her is your department and not ours, ma’am.” The trooper chimes in like a defense attorney. Ma’am this and Mrs. that. So the jurors forget I’m a doctor, a lawyer, a chief.

“No eating, drinking, smoking or borrowing the bathrooms.” I direct this at Hyde, and I’m giving him an order. “No dropping cigarette butts or gum wrappers or tossing fast-food bags, coffee cups, anything at all into the trash. Don’t assume this isn’t a crime scene.”

“But you don’t really think it is.”

“I’m working it like one and so should you,” I answer. “Because I won’t know what really happened here until I have more information. There was a lot of tissue response, a lot of bleeding, several liters I estimate. Her scalp is boggy. There may be more than one fracture. She has postmortem changes that I wouldn’t expect. I will tell you that much but I won’t know for a fact what we’ve got here until I get her to my office. And the air-conditioning turned off during a heat wave in August? I definitely don’t like that. Let’s not be so quick to blame her death on marijuana. You know what they say.”

“About what?” The trooper looks perplexed and worried, and he and the others have backed up several more steps.

“Better to be around potheads than drunks. Booze gives you dangerous impulses like climbing ladders or driving a car or getting into fights. Weed isn’t quite so motivating. It isn’t generally known for causing aggression or risk taking. Usually it’s quite the opposite.”

“It depends on the person and what they’re smoking, right? And maybe what other meds they’re on?”

“In general that’s true.”

“So let me ask you this. Would you expect someone who fell off a ladder to bleed this much?”

“It depends on what the injuries are,” I reply.

“So if they’re worse than you think and she’s negative for drugs and alcohol, that might be a big problem is what you’re saying.”

“Whatever happened is already a big problem you ask me.” It’s the trooper again between coughs.

“Certainly it was for her. When’s the last time you had a tetanus shot?” I ask him.

“Why?”

“Because a DTaP vaccination protects against tetanus but also pertussis. And I’m concerned you might have whooping cough.”

“I thought only kids got that.”

“Not true. How did your symptoms start?”

“Just a cold. Runny nose, sneezing about two weeks ago. Then this cough. I get fits and can hardly breathe. I don’t remember the last time I had a tetanus shot to be honest.”

“You need to see your doctor. I’d hate for you to get pneumonia or collapse a lung,” I say to the trooper.

Then he and the other officers finally leave me alone.

4 (#ulink_2f1b454d-cb7e-55f5-bc4b-b4e0cddfd583)

Eight minutes into the video and all I see is Lucy’s empty dorm room. I again try to save the file or pause it. I can’t. It just keeps playing like life passing by with nothing to show for it.

Now nine minutes into the clip and the dorm room is exactly the same, empty and quiet, but in the background the firing ranges are busy. Gunshots pop and I can see glaring light seeping around the edges of the white blinds closed the wrong way. The sun is directly in the windows and I remember Lucy’s room faced west. It’s late afternoon.

Pop-Pop. Pop-Pop.

I detect the rumbling noise of traffic driving by four floors below on J. Edgar Hoover Road, the main drag that runs through the middle of the FBI Academy. Rush hour. Classes ending for the day. Cops, agents coming in from the ranges. For an instant I imagine I smell the sharp banana odor of isoamyl acetate, of Hoppe’s gun-cleaning solvent. I smell burnt gunpowder as if it’s all around me. I feel the sultry Virginia heat and hear the static of insects where cartridge cases shine silver and gold in the sun-warmed grass. It all comes back to me powerfully, and then at last something happens.

The video has a title sequence. It begins to roll by very slowly:

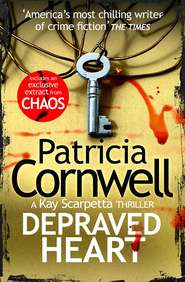

DEPRAVED HEART—SCENE 1

BY CARRIE GRETHEN

QUANTICO, VIRGINIA—JULY 11, 1997

The name is jolting. It’s infuriating to see it in bold red type going by ever so slowly, languidly, dripping down the screen pixel-by-pixel like a slow-motion bleed. Music has been added. Karen Carpenter is singing “We’ve Only Just Begun.” It’s obnoxious to score the video to that angelic voice, to those gentle Paul Williams lyrics.

Such a sweet loving song permuted into a threat, a mockery, a promise of more injury to come, of misery, harassment and possibly death. Carrie Grethen is flaunting and taunting. She’s giving me the finger. I haven’t listened to the Carpenters in years but in the old days I wore out their cassettes and CDs. I wonder if Carrie knew that. She probably did. So this is the next installment of what she must have put into the works a long time ago.

I feel the challenge and my response bubbling up like molten lava, and I’m keenly aware of my rage, of my lust to destroy the most reprehensible and treacherous female offender I’ve ever come across. For the past thirteen years I hadn’t given her a thought, not since I witnessed her die in a helicopter crash. Or I believed I did. But I was wrong. She was never in that flying machine, and when I found that out it was one of the worst things I’ve ever had to accept. It’s like being told your fatal disease is no longer in remission. Or that some horrific tragedy wasn’t just a bad dream.

So now Carrie continues what she’s started. Of course she would, and I remember my husband Benton’s recent warnings about bonding with her, about talking to her in my mind and settling into the easy belief that she doesn’t plan to finish what she started. She doesn’t want to kill me because she’s planned something worse. She doesn’t want to rid the earth of me or she would have this past June. Benton is a criminal intelligence analyst for the FBI, what people still call a profiler. He thinks I’ve identified with the aggressor. He suggests I’m suffering from Stockholm syndrome. He’s been suggesting it a lot of late. Every time he does we get into an argument.

“Doc? How we doing in here?” The approaching male voice is carried by the papery sounds of plasticized booties. “I’m ready to do the walk-through if you are.”

“Not yet,” I reply as Karen Carpenter continues to sing in my earpiece.

Workin’ together day to day, together, together …

He lumbers into the foyer. Peter Rocco Marino. Or Marino as most people refer to him, including me. Or Pete although I’ve never called him that and I’m not sure why except we didn’t start out as friends. Then there’s bastardo when he’s a jerk, and asshole when he’s one of those. About six-foot-three, at least 250 pounds with tree trunk thighs and hands as big as hubcaps, he has a massive presence that confuses my metaphors.

His face is broad and weathered with strong white teeth, an action hero jaw, a bullish neck and a chest as wide as a door. He has on a gray Harley-Davidson polo shirt, Herman Munster–size sneakers, tube socks, and khaki shorts that are baggy with bulging cargo pockets. Clipped to his belt are his badge and pistol but he doesn’t need credentials to do whatever he wants and get the respect he demands.

Marino is a cop without borders. His jurisdiction may be Cambridge but he finds ways to extend his legal reach far beyond the privileged boundaries of MIT and Harvard, beyond the luminaries who live here and the tourists who don’t. He shows up anywhere he’s invited and more often where he’s not. He has a problem with boundaries. He’s always had a problem with mine.

“Thought you’d want to know the marijuana is medical. I got no idea where she got it.” His bloodshot eyes move over the body, the bloody marble floor, and then land on my chest, his favorite place to park his attention.