Полная версия:

Warriors of the Storm

BERNARD CORNWELL

Warriors of the Storm

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 2015

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Cover illustration © Lee Gibbons/Tom Moon – www.leegibbons.co.uk

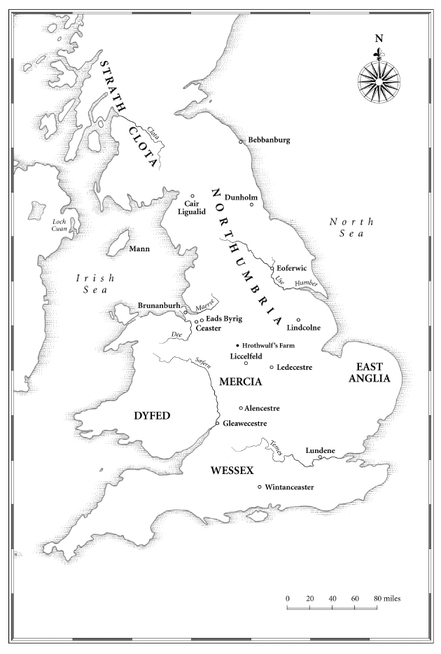

Map © John Gilkes 2015

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780007504091

Ebook Edition © 2016 ISBN: 9780007504084

Version: 2017-05-08

Dedication

Warriors of the Storm

is for

Phil and Robert

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Place Names

Part One: Flames on the River

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Part Two: The Ghost Fence

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Part Three: War of the Brothers

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Historical Note

Enjoyed Warrior of the Storm?

About the Author

Also by Bernard Cornwell

About the Publisher

PLACE NAMES

The spelling of place names in Anglo-Saxon England was an uncertain business, with no consistency and no agreement even about the name itself. Thus London was variously rendered as Lundonia, Lundenberg, Lundenne, Lundene, Lundenwic, Lundenceaster and Lundres. Doubtless some readers will prefer other versions of the names listed below, but I have usually employed whichever spelling is cited in either the Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names or the Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names for the years nearest or contained within Alfred’s reign, AD 871–899, but even that solution is not foolproof. Hayling Island, in 956, was written as both Heilincigae and Hæglingaiggæ. Nor have I been consistent myself; I have preferred the modern form Northumbria to Norðhymbralond to avoid the suggestion that the boundaries of the ancient kingdom coincide with those of the modern county. So this list, like the spellings themselves, is capricious.

Æsc’s Hill Ashdown, Berkshire Alencestre Alcester, Warwickshire Beamfleot Benfleet, Essex Bebbanburg Bamburgh Castle, Northumberland Brunanburh Bromborough, Cheshire Cair Ligualid Carlisle, Cumbria Ceaster Chester, Cheshire Cent Kent Contwaraburg Canterbury, Kent Cumbraland Cumbria Dunholm Durham, County Durham Dyflin Dublin, Eire Eads Byrig Eddisbury Hill, Cheshire Eoferwic York, Yorkshire Gleawecestre Gloucester, Gloucestershire Hedene River Eden, Cumbria Horn Hofn, Iceland Hrothwulf’s farm Rocester, Staffordshire Jorvik York, Yorkshire Ledecestre Leicester, Leicestershire Liccelfeld Lichfield, Staffordshire Lindcolne Lincoln, Lincolnshire Loch Cuan Strangford Lough, Northern Ireland Lundene London Mærse River Mersey Mann Isle of Man Sæfern River Severn Strath Clota Strathclyde, Scotland Use River Ouse Wiltunscir Wiltshire Wintanceaster Winchester, Hampshire Wirhealum The Wirral, CheshirePART ONE

Flames on the River

ONE

There was fire in the night. Fire that seared the sky and paled the stars. Fire that churned thick smoke across the land between the rivers.

Finan woke me. ‘Trouble,’ was all he said.

Eadith stirred and I pushed her away from me. ‘Stay there,’ I told her and rolled out from under the fleeces. I fumbled for a bearskin cloak and pulled it around my shoulders before following Finan into the street. There was no moon, just the flames reflecting from the great pall of smoke that drifted inland on the night wind. ‘We need more men on the walls,’ I said.

‘Done it,’ Finan said.

So all that was left for me to do was curse. I cursed.

‘It’s Brunanburh,’ Finan said bleakly and I cursed again.

Folk were gathering in Ceaster’s main street. Eadith had come from the house, wrapped in a great cloak and with her red hair shining in the light of the lanterns that burned at the church door. ‘What is it?’ she asked sleepily.

‘Brunanburh,’ Finan said grimly. Eadith made the sign of the cross. I had a glimpse of her naked body as her hand slipped from beneath the cloak to touch her forehead, then she clutched the heavy woollen cloth tight to her belly again.

‘Loki,’ I spoke the name aloud. He is the god of fire, whatever the Christians might tell you. And Loki is the most slippery of all the gods, a trickster who deceives, charms, betrays and hurts us. Fire is his two-edged weapon that can warm us, cook for us, scorch us, or kill us. I touched Thor’s hammer that hung from my neck. ‘Æthelstan’s there,’ I said.

‘If he lives,’ Finan said.

There was nothing to be done in the darkness. The journey to Brunanburh took at least two hours on horseback and would take longer in this dark night, when we would be stumbling through woods and possibly riding into an ambush set by the men who had fired the distant burh. All I could do was watch from Ceaster’s walls in case an attack burst from the dawn.

I did not fear such an attack. Ceaster had been built by the Romans and it was as tough a fortress as any in Britain. The Northmen would need to cross a flooded ditch and put ladders against the high stone walls, and Northmen have ever been reluctant to attack fortresses. But Brunanburh was aflame, so who knew what unlikely things the dawn might bring? Brunanburh was our newest burh, built by Æthelflaed who ruled over Mercia, and it guarded the River Mærse, which offered the Northmen’s boats an easy route into central Britain. In years past the Mærse had been busy, the oars dipping and pulling, and the dragon-headed boats surging against the river’s current to bring new warriors to the unending struggle between the Northmen and the Saxons, but Brunanburh had stopped that traffic. We kept a fleet of twelve ships there, their crews protected by Brunanburh’s thick timber walls, and the Northmen had learned to fear those ships. Now, if they landed on Britain’s west coast, they went to Wales or else to Cumbraland, which was the fierce wild country north of the Mærse.

Except tonight. Tonight there were flames by the Mærse.

‘Get dressed,’ I told Eadith. There would be no more sleep this night.

She touched the emerald encrusted cross at her neck. ‘Æthelstan,’ she said softly as if she prayed for him while fingering the cross. She had become fond of Æthelstan.

‘He either lives or is dead,’ I said curtly, ‘and we won’t know till the dawn.’

We rode just before the dawn, rode north in the wolf-light, following the paved road through the shadowed cemetery of Roman dead. I took sixty men, all mounted on fast light horses so that if we ran into an army of howling Northmen we could flee. I sent scouts ahead, but we were in a hurry so there was no time for our normal precaution, which was to wait for the scouts’ reports before we rode on. Our warning this time would be the death of the scouts. We left the Roman road to follow the track we had made through the woods. Clouds had come from the west and a drizzle was falling, but still the smoke rose ahead of us. Rain might extinguish Loki’s fire, but not drizzle, and the smoke mocked and beckoned us.

Then we came from the woods to where the fields turned into mudflats and the mudflats merged with the river, and there, far to our west on that wide stretch of silver-grey water, was a fleet. Twenty, thirty ships, maybe more, it was impossible to tell because they were moored so close together, but even from far away I could see that their prows were decorated with the Northmen’s beasts; with eagles, dragons, serpents, and wolves. ‘Sweet God,’ Finan said, appalled.

We hurried now, following a cattle track that meandered along higher ground on the river’s southern bank. The wind was in our faces, gusting suddenly to send ripples scurrying across the Mærse. We still could not see Brunanburh because the fort lay beyond a wooded rise, but a sudden movement at the wood’s edge betrayed the presence of men, and my two scouts turned their horses and galloped back towards us. Whoever had alarmed them vanished into the thick spring leaves and a moment later a horn sounded, the noise mournful in the grey damp dawn.

‘It’s not the fort burning,’ Finan said uncertainly.

Instead of answering I swerved inland off the track onto the lush pasture. The two scouts came close, their horses’ hooves hurling up clods of damp turf. ‘There are men in the trees, lord!’ one shouted. ‘At least a score, probably more!’

‘And ready for a fight,’ the other reported.

‘Ready for a fight?’ Finan asked.

‘Shields, helmets, weapons,’ the second man explained.

I led my sixty men southwards. The belt of young woodland stood like a barrier between us and Brunanburh, and if an enemy waited then they would surely be barring the track. If we followed the track we could ride straight into their shield wall hidden among the trees, but by cutting inland I would force them to move, to lose their order, and so I quickened the pace, kicking my horse into a canter. My son rode up on my left side. ‘It’s not the fort burning!’ he shouted.

The smoke was thinning. It still rose beyond the trees, a smear of grey that melted into the low clouds. It seemed to be coming from the river, and I suspected Finan and my son were right, that it was not the fort burning, but rather the ships. Our ships. But how had an enemy reached those ships? If they had come by daylight they would have been seen and the fort’s defenders would have manned the boats and challenged the enemy, while coming by night seemed impossible. The Mærse was shallow and barred with mudbanks, and no shipmaster could hope to bring a vessel this far inland in the dark of a moonless night.

‘It’s not the fort!’ Uhtred called to me again. He made it sound like good news, but my fear was that the fort had fallen and its stout timber walls now protected a horde of Northmen. Why should they burn what they could easily defend?

The ground was rising. I could see no enemy in the trees. That did not mean they were not there. How many enemy? Thirty ships? That could easily be a thousand men, and those men must have known that we would ride from Ceaster. If I had been the enemy’s leader I would be waiting just beyond the trees, and that suggested I should slow our advance and send the scouts ahead again, but instead I kicked the horse. My shield was on my back and I left it there, just loosening Serpent-Breath in her scabbard. I was angry and I was careless, but instinct told me that no enemy waited just beyond the woodland. They might have been waiting on the track, but by swerving inland I had given them little time to reform a shield wall on the higher ground. The belt of trees still hid what lay beyond, and I turned the horse and rode west again. I plunged into the leaves, ducked under a branch, let the horse pick its own way through the wood, and then I was through the trees, and I hauled on the reins, slowing, watching, stopping.

No enemy.

My men crashed through the undergrowth and stopped behind me.

‘Thank Christ,’ Finan said.

The fort had not been taken. The white horse of Mercia still flew above the ramparts and with it was Æthelflaed’s goose flag. A third banner hung from the walls, a new banner I had ordered made by the women of Ceaster. It showed the dragon of Wessex, and the dragon was holding a lightning bolt in one raised claw. It was Prince Æthelstan’s symbol. The boy had asked to have a Christian cross on his flag, but I had ordered the lightning bolt embroidered there instead.

I called Æthelstan a boy, but he was a young man now. He had grown tall, and his boyish mischief had been tempered by experience. There were men who wanted Æthelstan dead, and he knew it, and so his eyes had become watchful. He was handsome too, or so Eadith told me, those watchful grey eyes set in a strong-boned face beneath hair black as a raven’s wing. I called him Prince Æthelstan, while those men who wanted him dead called him a bastard.

And many folk believed their lies. Æthelstan had been born to a pretty Centish girl who had died whelping him, but his father was Edward, son of King Alfred and now king of Wessex himself. Edward had since married a West Saxon girl and fathered another son, which made Æthelstan an inconvenience, especially as it was rumoured that in truth he was not a bastard at all because Edward had secretly married the girl from Cent. True or not, and I had good cause to know the story of the first marriage was entirely true, it did not matter because to many in his father’s kingdom Æthelstan was the unwanted son. He had not been raised in Wintanceaster like Edward’s other children, but sent to Mercia. Edward professed to like the boy, but ignored him, and in truth Æthelstan was an embarrassment. He was the king’s eldest son, the ætheling, but he had a younger half-brother whose vengeful mother wanted Æthelstan dead because he stood between her son and the throne of Wessex. But I liked Æthelstan. I liked him enough to want him to reach the throne that was his birthright, but to be king he first needed to learn a man’s responsibilities, and so I had given him command of the fort and of the fleet at Brunanburh.

And now the fleet was gone. It was burned. The hulls were smoking beside the charred remnants of the pier we had spent a year building. We had driven elm pilings deep into the foreshore and thrust the walkway out past the low water mark to make a wharf where a battle fleet could be ever ready. Now the wharf was gone, along with the sleek high-prowed ships. Four of those ships had been stranded above the tide mark and were still smouldering, the rest were just blackened ribs in the shallow water, while, at the pier’s end, three dragon-headed ships lay moored against the scorched pilings. Five more ships lay just beyond, using their oars to hold the hulls against the river’s current and the ebbing tide. The rest of the enemy fleet was a half mile upriver.

And ashore, between us and the burned wharf, were men. Men in mail, men with shields and helmets, men with spears and swords. There were perhaps two hundred of them, and they had herded what few cattle they could find and were pushing the beasts towards the river bank where they were being slaughtered so the flesh could be carried away. I glanced at the fort. Æthelstan commanded a hundred and fifty men there, and I could see them thick on the ramparts, but he was making no attempt to impede the enemy’s retreat. ‘Let’s kill some of the bastards,’ I said.

‘Lord?’ Finan asked, wary of the enemy’s greater number.

‘They’ll run,’ I said. ‘They want the safety of their ships, they don’t want a fight on land.’

I drew Serpent-Breath. The Norsemen who had come ashore were all on foot, and they were scattered. Most were close to the burned wharf’s landward end where they could quickly form a shield wall, but dozens of others were struggling with the cattle. I aimed for those men.

And I was angry. I commanded the garrison at Ceaster, and Brunanburh was a part of that garrison. It was an outlying fort and it had been surprised and its ships had been burned and I was angry. I wanted blood in the dawn. I kissed Serpent-Breath’s hilt then struck back with my spurs, and we went down that shallow slope at the full gallop, our swords drawn and spears reaching. I wished I had brought a spear, but it was too late for regrets. The cattle herders saw us and tried to run, but they were on the mudflats and the cattle were panicking and our hooves were loud on the dew-wet turf. The largest group of enemy was making a shield wall where the charred remains of the pier reached dry land, but I had no intention of fighting them. ‘I want prisoners!’ I bellowed at my men, ‘I want prisoners!’

One of the Northmen’s ships started for the beach, either to reinforce the men ashore or to offer them an escape. A thousand white birds rose from the grey water, calling and shrieking, circling above the pasture where the shield wall had formed. I saw a banner raised above the locked shields, but I had no time to look at that standard because my horse thundered across the track, down the bank and onto the foreshore. ‘Prisoners!’ I shouted again. I passed a slaughtered bullock, its blood thick and black on the mud. The men had started to butcher it, but had fled, and then I was among those fugitives and I used the flat of Serpent-Breath’s blade to knock one man down. I turned. My horse slipped in the mud, reared, and as he came down I used his weight to drive Serpent-Breath into a second man’s chest. The blade pierced his shoulder, drove deep, blood bubbled at his mouth and I kicked the stallion so he would drag the heavy blade free of the dying man. Finan went past me, then my son galloped by, holding his sword Raven-Beak low and bending from the saddle to plunge it into a running man’s back. A wild-eyed Norseman swung an axe at me, which I avoided easily, then Berg Skallagrimmrson’s spear blade went through the man’s spine, through his guts, and showed bright and blood-streaked at his belly. Berg was riding bare-headed, his fair hair, long as a woman’s, was hung with knuckle bones and ribbons. He grinned at me as he let go of the spear’s ash pole and drew his sword. ‘I ruined his mail, lord!’

‘I want prisoners, Berg!’

‘I kill some bastards first, yes?’ He spurred away, still grinning. He was a Norse warrior, maybe eighteen or nineteen summers old, but he had already rowed a ship to Horn on the island of fire and ice that lay far off in the Atlantic, and he had fought in Ireland, in Scotland, and in Wales, and he had stories of rowing inland through forests of birch trees, which, he claimed, grew east of the Norsemen’s land. There were frost giants there, he told me, and wolves the size of stallions. ‘I should have died a thousand times, lord,’ he told me, but he was only alive now because I had saved his life. He had become my man, sworn to me, and in my service he took the head from a fugitive with one swing of his sword. ‘Yah!’ he bellowed back to me, ‘I sharpen the blade good!’

Finan was close to the water’s edge, close enough that a man on the approaching ship hurled a spear at him. The weapon stuck in the mud, and Finan contemptuously bent from the saddle to seize the shaft and spurred to where a man lay fallen and bleeding in the mud. He looked back to the ship, making sure he was being watched, then raised the spear ready to plunge the blade into the wounded man’s belly. Then he paused and, to my surprise, tossed the spear away. He dismounted and knelt by the wounded man, talked for a moment and then stood. ‘Prisoners,’ he shouted, ‘we need prisoners!’

A horn sounded from the fort and I turned to see men pouring out of Brunanburh’s gate. They came with shields, spears, and swords, ready to make a wall that would drive the enemy’s shield wall into the river, but those invaders were already leaving and needed no help from us. They were wading past the charred pilings, and edging around the smoking boats to clamber aboard the nearest ships. The approaching ship paused, churning the shallows with its oars, reluctant to face my men, who called insults to them and waited at the river’s edge with drawn swords and bloodied spears. More of the enemy waded out towards the dragon-headed boats. ‘Let them be!’ I shouted. I had wanted blood in the dawn, but there was no advantage in slaughtering a handful of men in the Mærse’s shallows and losing maybe a dozen myself. The enemy’s main fleet, which had to contain hundreds more men, was already rowing upriver. To weaken it I needed to kill those hundreds, not just a few.

The crews of the nearer ships were jeering at us. I watched as men were hauled aboard, and I wondered where this fleet had come from. It had been years since I had seen so many northern ships. I kicked my horse to the water’s edge. A man hurled a spear, but it fell short, and I deliberately sheathed Serpent-Breath to show the enemy I accepted that the fight was over, and I saw a grey-bearded man strike the elbow of a youth who wanted to throw another spear. I nodded to the greybeard, who raised a hand in acknowledgement.