Полная версия:

War of the Wolf

WAR OF THE WOLF

BERNARD CORNWELL

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 2018

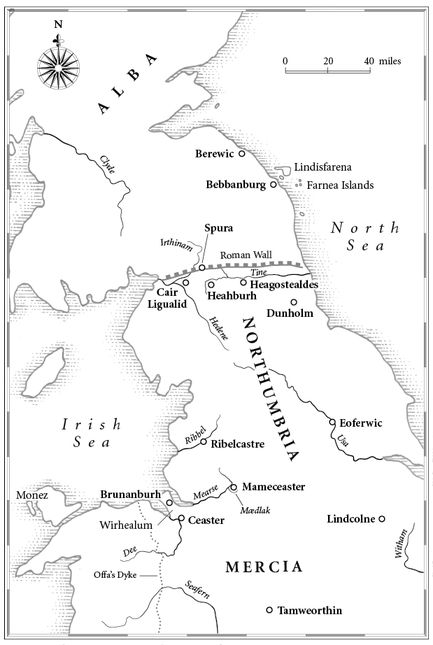

Map © John Gilkes 2018

Plan of the Roman fort adapted from a drawing by Thomas Sopwith

Jacket design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Jacket photography © CollaborationJS

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008183837

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2018 ISBN: 9780008183851

Version 2018-08-02

Dedication

War of the Wolf

is dedicated to the memory of

Toby Eady,

my agent and dear friend.

1941–2017

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Place Names

Part One: The Wild Lands

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Two: Eostre’s Feast

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Part Three: Fortress of the Eagles

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Historical Note

About the Author

Also by Bernard Cornwell

About the Publisher

PLACE NAMES

The spelling of place names in ninth- and tenth-century Britain was an uncertain business, with no consistency and no agreement even about the name itself. Thus London was variously rendered as Lundonia, Lundenberg, Lundenne, Lundene, Lundenwic, Lundenceaster and Lundres. Doubtless some readers will prefer other versions of the names listed below, but I have usually employed whichever spelling is cited in either the Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names or the Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names for the years nearest or contained within Alfred’s reign, AD 871–899, but even that solution is not foolproof. Hayling Island, in 956, was written as both Heilincigae and Hæglingaiggæ. Nor have I been consistent myself; I have preferred the modern form Northumbria to Norðhymbralond to avoid the suggestion that the boundaries of the ancient kingdom coincide with those of the modern county. So this list, like the spellings themselves, is capricious.

Bebbanburg — Bamburgh, Northumberland

Berewic — Berwick on Tweed, Northumberland

Brunanburh — Bromborough, Cheshire

Cair Ligualid — Carlisle, Cumbria

Ceaster — Chester, Cheshire

Cent — Kent

Contwaraburg — Canterbury, Kent

Dunholm — Durham, County Durham

Dyflin — Dublin, Eire

Eoferwic — York, Yorkshire (Saxon name)

Fagranforda — Fairford, Gloucestershire

Farnea Islands — Farne Islands, Northumberland

Gleawecestre — Gloucester, Gloucestershire

Heagostealdes — Hexham, Northumberland

Heahburh — Whitley Castle, Alston, Cumbria

(fictional name)

Hedene — River Eden, Cumbria

Huntandun — Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire

Hwite — Whitchurch, Shropshire

Irthinam — River Irthing

Jorvik — York, Yorkshire (Danish/Norse name)

Lindcolne — Lincoln, Lincolnshire

Lindisfarena — Lindisfarne (Holy Island), Northumberland

Lundene — London

Mædlak — River Medlock, Lancashire

Mærse — River Mersey

Mameceaster — Manchester

Monez — Anglesey, Wales

Ribbel — River Ribble, Lancashire

Ribelcastre — Ribchester, Lancashire

Snæland — Iceland

Spura — Birdoswald Roman fort, Cumbria (fictional name)

Sumorsæte — Somerset

Tamweorthin — Tamworth, Staffordshire

Temes — River Thames

Tine — River Tyne

Usa — River Ouse, Yorkshire

Wevere — River Weaver, Cheshire

Wiltunscir — Wiltshire

Wintanceaster — Winchester, Hampshire

Wirhealum — The Wirral, Cheshire

PART ONE

The Wild Lands

One

I did not go to Æthelflaed’s funeral.

She was buried in Gleawecestre in the same vault as her husband, whom she had hated.

Her brother, King Edward of Wessex, was chief mourner and, when the rites were done and Æthelflaed’s corpse had been walled up, he stayed in Gleawecestre. His sister’s strange banner of the holy goose was lowered over the palace, and the dragon of Wessex was hoisted in its place. The message could not have been plainer. Mercia no longer existed. In all the British lands south of Northumbria and east of Wales there was only one kingdom and one king. Edward sent me a summons, demanding I travel to Gleawecestre and swear fealty to him for the lands I owned in what had been Mercia, and the summons bore his name followed by the words Anglorum Saxonum Rex. King of the Angles and the Saxons. I ignored the document.

Within a year a second document reached me, this one signed and sealed in Wintanceaster. By the grace of God, it told me, the lands granted to me by Æthelflaed of Mercia were now forfeited to the bishopric of Hereford, which, the parchment assured me, would employ said lands to the furtherance of God’s glory. ‘Meaning Bishop Wulfheard will have more silver to spend on his whores,’ I told Eadith.

‘Maybe you should have gone to Gleawecestre?’ she suggested.

‘And swear loyalty to Edward?’ I spat the name. ‘Never. I don’t need Wessex and Wessex doesn’t need me.’

‘So what will you do about the estates?’ she asked.

‘Nothing,’ I said. What could I do? Go to war against Wessex? It annoyed me that Bishop Wulfheard, an old enemy, had taken the land, but I had no need of Mercian lands. I owned Bebbanburg. I was a Northumbrian lord, and owned all that I wanted. ‘Why should I do anything?’ I growled at Eadith. ‘I’m old and I don’t need trouble.’

‘You’re not old,’ she said loyally.

‘I’m old,’ I insisted. I was over sixty, I was ancient.

‘You don’t look old.’

‘So Wulfheard can plough his whores and let me die in peace. I don’t care if I never see Wessex or Mercia ever again.’

Yet a year later I was in Mercia, mounted on Tintreg, my fiercest stallion, and wearing a helmet and mail, and with Serpent-Breath, my sword, slung at my left hip. Rorik, my servant, carried my heavy iron-rimmed shield, and behind us were ninety men, all armed, and all mounted on war horses.

‘Sweet Jesus,’ Finan said beside me. He was gazing at the enemy in the valley beneath us. ‘Four hundred of the bastards?’ he paused. ‘At least four hundred. Maybe five?’

I said nothing.

It was late on a winter’s afternoon, and bitterly cold. The horses’ breath misted among the leafless trees that crowned the gentle ridge from where we watched our enemy. The sun was sinking and hidden by clouds, which meant no betraying sparks of light could be reflected from our mail or weapons. Away to my right, to the west, the River Dee lay flat and grey as it widened towards the sea. On the lower ground in front of us was the enemy and, beyond them, Ceaster.

‘Five hundred,’ Finan decided.

‘I never thought I’d see this place again,’ I said. ‘Never wanted to see it again.’

‘They broke the bridge,’ Finan said, peering far to the south.

‘Wouldn’t you, in their place?’

The place was Ceaster, and our enemy was besieging the city. Most of that enemy was to the east of the city, but smoking campfires betrayed plenty to the city’s north. The River Dee flowed just south of the city walls, then turned north towards its widening estuary, and by breaking the central span of the ancient Roman bridge, the enemy had ensured that no relief force could come from the south. If the city’s small garrison was to fight its way out of the trap they would need to come north or east where the enemy was strongest. And that garrison was small. I had been told, though it was nothing more than a guess, that fewer than a hundred men held the city.

Finan must have been thinking the same thing. ‘And five hundred men couldn’t take the city?’ he said derisively.

‘Nearer six hundred?’ I suggested mildly. It was hard to estimate the enemy because many of the folk in the besiegers’ encampment were women and children, but I thought Finan’s guess was low. Tintreg lowered his head and snorted. I patted his neck, then touched Serpent-Breath’s hilt for luck. ‘I wouldn’t want to assault those walls,’ I said. Ceaster’s stone walls had been built by the Romans, and the Romans had built well. And the city’s small garrison, I thought, had been well led. They had repelled the early assaults, and so the enemy had settled down to starve them out.

‘So, what do we do?’ Finan asked.

‘Well, we’ve come a long way,’ I said.

‘So?’

‘So it seems a pity not to fight.’ I gazed at the city. ‘If what we were told is true, then the poor bastards in the city will be eating rats by now. And that lot?’ I nodded down to the campfires. ‘They’re cold, they’re bored, and they’ve been here too long. They got bloodied when they attacked the walls, so now they’re just waiting.’

I could see the thick barricades that the besiegers had made outside Ceaster’s northern and eastern gates. Those barricades would be guarded by the enemy’s best troops, posted there to stop the garrison sallying out or trying to escape. ‘They’re cold,’ I said again, ‘they’re bored, and they’re useless.’

Finan smiled. ‘Useless?’

‘They’re mostly from the fyrd,’ I said. The fyrd is an army raised from field labourers, shepherds, common men. They might be brave, but a trained house-warrior, like the ninety who followed me, was far more lethal. ‘Useless,’ I said again, ‘and stupid.’

‘Stupid?’ Berg, mounted on his stallion behind me, asked.

‘No sentries out here! They should never have let us get this close. They have no idea we’re here. And stupidity gets you killed.’

‘I like that they’re stupid,’ Berg said. He was a Norseman, young and savage, frightened of nothing except the disapproval of his young Saxon wife.

‘Three hours to sunset?’ Finan suggested.

‘Let’s not waste them.’

I turned Tintreg, going back through the trees to the road that led to Ceaster from the ford of the Mærse. The road brought back memories of riding to face Ragnall, and of Haesten’s death, and now the road was leading me towards another fight.

Though we looked anything but threatening as we rode down the long, gentle slope. We did not hurry. We came like men who were finishing a long journey, which was true, and we kept our swords in their scabbards and our spears bundled on the packhorses led by our servants. The enemy must have seen us almost as soon as we emerged from the wooded ridge, but we were few and they were many, and our ambling approach suggested we came in peace. The high stone wall of the city was in shadow, but I could make out the banners hanging from the ramparts. They showed Christian crosses, and I remembered Bishop Leofstan, a holy fool and a good man, who had been chosen as Ceaster’s bishop by Æthelflaed. She had strengthened and garrisoned the city-fort as a bulwark against the Norse and Danes who crossed the Irish Sea to hunt for slaves in the Saxon lands.

Æthelflaed, Alfred’s daughter, and ruler of Mercia. Dead now. Her corpse was decaying in a cold stone vault. I imagined her dead hands clutching a crucifix in the grave’s foul darkness, and remembered those same hands clawing my spine as she writhed beneath me. ‘God forgive me,’ she would say, ‘don’t stop!’

And now she had brought me back to Ceaster.

And Serpent-Breath was about to kill again.

Æthelflaed’s brother ruled Wessex. He had been content to let his sister rule Mercia, but on her death he had marched West Saxon troops north across the Temes. They came, he said, to honour his sister at her funeral, but they stayed to impose Edward’s rule on his sister’s realm. Edward, Anglorum Saxonum Rex.

Those Mercian lords who bent their knee were rewarded, but some, a few, resented the West Saxons. Mercia was a proud land. There had been a time when the King of Mercia was the most powerful ruler of Britain, when the kings of Wessex and of East Anglia and the chieftains of Wales had sent tribute, when Mercia was the largest of all the British kingdoms. Then the Danes had come, and Mercia had fallen, and it had been Æthelflaed who had fought back, who had driven the pagans northwards and built the burhs that protected her frontier. And she was dead, mouldering, and her brother’s troops now guarded the burh walls, and the King of Wessex called himself king of all the Saxons, and he demanded silver to pay for the garrisons, and he took land from the resentful lords and gave it to his own men, or to the church. Always to the church, because it was the priests who preached to the Mercian folk that it was their nailed god’s will that Edward of Wessex be king in their land, and that to oppose the king was to oppose their god.

Yet fear of the nailed god did not prevent a revolt, and so the fighting had begun. Saxon against Saxon, Christian against Christian, Mercian against Mercian, and Mercian against West Saxon. The rebels fought under Æthelflaed’s flag, declaring that it had been her will that her daughter, Ælfwynn, succeed her. Ælfwynn, Queen of Mercia! I liked Ælfwynn, but she could no more have ruled a kingdom than she could have speared a charging boar. She was flighty, frivolous, pretty, and petty. Edward, knowing his niece had been named to the throne, took care to have her shut away in a convent, along with his discarded wife, but still the rebels flaunted her mother’s flag and fought in her name.

They were led by Cynlæf Haraldson, a West Saxon warrior whom Æthelflaed had wanted as a husband for Ælfwynn. The truth, of course, was that Cynlæf wanted to be King of Mercia himself. He was young, he was handsome, he was brave in battle, and, to my mind, stupid. His ambition was to defeat the West Saxons, rescue his bride from her convent, and be crowned.

But first he must capture Ceaster. And he had failed.

‘It feels like snow,’ Finan said as we rode south towards the city.

‘It’s too late in the year for snow,’ I said confidently.

‘I can feel it in my bones,’ he said, shivering. ‘It’ll come by nightfall.’

I scoffed at that. ‘Two shillings says it won’t.’

He laughed. ‘God send me more fools with silver! My bones are never wrong.’ Finan was Irish, my second-in-command, and my dearest friend. His face, framed by the steel of his helmet, looked lined and old, his beard was grey. Mine was too, I suppose. I watched as he loosened Soul-Stealer in her scabbard and as his eyes flicked across the smoke of the campfires ahead. ‘So what are we doing?’ he asked.

‘Scouring the bastards off the eastern side of the city,’ I said.

‘They’re thick there.’

I guessed that almost two thirds of the enemy were camped on Ceaster’s eastern flank. The campfires were dense there, burning between low shelters made of branches and turf. To the south of the crude shelters were a dozen lavish tents, placed close to the ruins of the old Roman arena, which, even though it had been used as a convenient quarry, still rose higher than the tents above which two flags hung motionless in the still air. ‘If Cynlæf’s still here,’ I said, ‘he’ll be in one of those tents.’

‘Let’s hope the bastard’s drunk.’

‘Or else he’s in the arena,’ I said. The arena was built just outside the city and was a vast hulk of stone. Beneath its banked stone seating were cave-like rooms that, when I had last explored them, were home to wild dogs. ‘If he had any sense,’ I went on, ‘he’d have abandoned this siege. Left men to keep the garrison starving, and gone south. That’s where the rebellion will be won or lost, not here.’

‘Does he have sense?’

‘Daft as a turnip,’ I said, and then started laughing. A group of women burdened with firewood had stepped off the road to kneel as we passed, and they looked up at me in astonishment. I waved at them. ‘We’re about to make some of them widows,’ I said, still laughing.

‘And that’s funny?’

I spurred Tintreg into a trot. ‘What’s funny,’ I said, ‘is that we’re two old men riding to war.’

‘You, maybe,’ Finan said pointedly.

‘You’re my age!’

‘I’m not a grandfather!’

‘You might be. You don’t know.’

‘Bastards don’t count.’

‘They do,’ I insisted.

‘Then you’re probably a great-grandfather by now.’

I gave him a harsh look. ‘Bastards don’t count,’ I snarled, making him laugh, then he made the sign of the cross because we had reached the Roman cemetery that stretched either side of the road. There were ghosts here, ghosts wandering between the lichen-covered stones with their fading inscriptions that only Christian priests who understood Latin could read. Years before, in a fit of zeal, a priest had started throwing down the stones, declaring they were pagan abominations. That very same day he was struck down dead and ever since the Christians had tolerated the graves, which, I thought, must be protected by the Roman gods. Bishop Leofstan had laughed when I told him that story, and had assured me that the Romans were good Christians. ‘It was our god, the one true god, who slew the priest,’ he had told me. Then Leofstan himself had died, struck down just as suddenly as the grave-hating priest. Wyrd bið ful a¯ræd.

My men were strung out now, not quite in single file, but close. None wanted to ride too near the road’s verges because that was where the ghosts gathered. The long, straggling line of horsemen made us vulnerable, but the enemy seemed oblivious to our threat. We passed more women, all bent beneath great burdens of firewood they had cut from spinneys north of the graves. The nearest campfires were close now. The afternoon’s light was fading, though dusk was still an hour or more away. I could see men on the northern city wall, see their spears, and knew they must be watching us. They would think we were reinforcements come to help the besiegers.

I curbed Tintreg just beyond the old Roman cemetery to let my men catch up. The sight of the graves and thinking of Bishop Leofstan had brought back memories. ‘Remember Mus?’ I asked Finan.

‘Christ! How could anyone forget her?’ He grinned. ‘Did you …’ he began.

‘Never. You?’

He shook his head. ‘Your son gave her a few good rides.’

I had left my son in command of the troops garrisoning Bebbanburg. ‘He’s a lucky boy,’ I said. Mus, her real name was Sunngifu, was small like a mouse, and had been married to Bishop Leofstan. ‘I wonder where Mus is now?’ I asked. I was still gazing at Ceaster’s northern wall, trying to estimate how many men stood guard on the ramparts. ‘More than I expected,’ I said.

‘More?’

‘Men on the wall,’ I explained. I could see at least forty men on the ramparts, and knew there must be just as many on the eastern wall, which faced the bulk of the enemy.

‘Maybe they were reinforced?’ Finan suggested.

‘Or the monk was wrong, which wouldn’t surprise me.’

A monk had come to Bebbanburg with news of Ceaster’s siege. We already knew of the Mercian rebellion, of course, and we had welcomed it. It was no secret that Edward, who now styled himself King of the Angles and Saxons, wanted to invade Northumbria and so make that arrogant title come true. Sigtryggr, my son-in-law and King of Northumbria, had been preparing for that invasion, fearing it too, and then came the news that Mercia was tearing itself apart, and that Edward, far from invading us, was fighting to hold onto his new lands. Our response was obvious; do nothing! Let Edward’s realm tear itself into shreds, because every Saxon warrior who died in Mercia was one less man to bring a sword into Northumbria.

Yet here I was, on a late winter’s afternoon beneath a darkening sky, coming to fight in Mercia. Sigtryggr had not been happy, and his wife, my daughter, even unhappier. ‘Why?’ she had demanded.

‘I took an oath,’ I had told them both, and that had stilled their protests.

Oaths are sacred. To break an oath is to invite the anger of the gods, and Sigtryggr had reluctantly agreed to let me relieve the siege of Ceaster. Not that he could have done much to stop me; I was his most powerful lord, his father-in-law, and the Lord of Bebbanburg, indeed he owed me his kingdom, but he insisted I take fewer than a hundred warriors. ‘Take more,’ he had said, ‘and the damned Scots will come over the frontier.’ I had agreed. I led just ninety men, and with those ninety I intended to save King Edward’s new kingdom.

‘You think Edward will be grateful?’ my daughter had asked, trying to find some good news in my perverse decision. She was thinking that Edward’s gratitude might persuade him to abandon his plans to invade Northumbria.

‘Edward will think I’m a fool.’

‘You are!’ Stiorra had said.

‘Besides, I hear he’s sick.’

‘Good,’ she had said vengefully. ‘Maybe his new wife has worn him out?’

Edward would not be grateful, I thought, whatever happened here. Our horses’ hooves were loud on the Roman road. We still rode slowly, showing no threat. We passed the old worn stone pillar that said it was one mile to Deva, the name the Romans had given Ceaster. By now we were among the hovels and campfires of the encampment, and folk watched us pass. They showed no alarm, there were no sentries, and no one challenged us. ‘What’s wrong with them?’ Finan growled at me.