Полная версия:

Vagabond

VAGABOND

BERNARD CORNWELL

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2002

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 2002

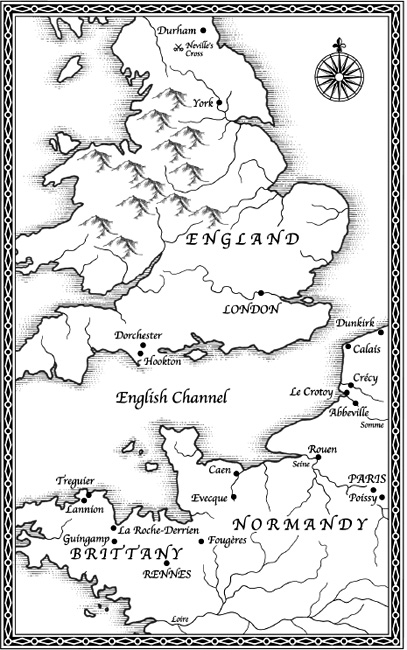

Map © John Gilkes 2013

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007310319

Ebook Edition © JULY 2009 ISBN: 9780007338795

Version: 2018-08-16

VAGABOND

is for June and Eddie Bell

in friendship and gratitude

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Part One: ARROWS ON THE HILL

It was October …

A rush of …

Thomas, Father Hobbe …

Sir William Douglas …

Part Two: THE WINTER SIEGE

It was dark …

It was the …

A single short …

The English had …

Part Three: THE KING’S CUPBEARER

Jeanette Chenier, Comtesse …

Lodewijk – he insisted …

Thomas lay shivering …

The first stone …

Richard Totesham watched …

Historical Note

Keep Reading

About the Author

Praise

Also by Bernard Cornwell

About the Publisher

PART ONE

England, October 1346

Arrows on the Hill

It was October, the time of the year’s dying when cattle were being slaughtered before winter and when the northern winds brought a promise of ice. The chestnut leaves had turned golden, the beeches were trees of flame and the oaks were made from bronze. Thomas of Hookton, with his woman, Eleanor, and his friend, Father Hobbe, came to the upland farm at dusk and the farmer refused to open his door, but shouted through the wood that the travellers could sleep in the byre. Rain rattled on the mouldering thatch. Thomas led their one horse under the roof that they shared with a woodpile, six pigs in a stout timber pen and a scattering of feathers where a hen had been plucked. The feathers reminded Father Hobbe that it was St Gallus’s day and he told Eleanor how the blessed saint, coming home in a winter’s night, had found a bear stealing his dinner. ‘He told the animal off!’ Father Hobbe said. ‘He gave it a right talking-to, he did, and then he made it fetch his firewood.’

‘I’ve seen a picture of that,’ Eleanor said. ‘Didn’t the bear become his servant?’

‘That’s because Gallus was a holy man,’ Father Hobbe explained. ‘Bears wouldn’t fetch firewood for just anyone! Only for a holy man.’

‘A holy man,’ Thomas put in, ‘who is the patron saint of hens.’ Thomas knew all about the saints, more indeed than Father Hobbe. ‘Why would a chicken want a saint?’ he enquired sarcastically.

‘Gallus is the patron of hens?’ Eleanor asked, confused by Thomas’s tone. ‘Not bears?’

‘Of hens,’ Father Hobbe confirmed. ‘Indeed of all poultry.’

‘But why?’ Eleanor wanted to know.

‘Because he once expelled a wicked demon from a young girl.’ Father Hobbe, broad-faced, hair like a stickleback’s spines, peasant-born, stocky, young and eager, liked to tell stories of the blessed saints. ‘A whole bundle of bishops had tried to drive the demon out,’ he went on, ‘and they had all failed, but the blessed Gallus came along and he cursed the demon. He cursed it! And it screeched in terror’ – Father Hobbe waved his hands in the air to imitate the evil spirit’s panic – ‘and then it fled from her body, it did, and it looked just like a black hen – a pullet. A black pullet.’

‘I’ve never seen a picture of that,’ Eleanor remarked in her accented English, then, gazing out through the byre door, ‘but I’d like to see a real bear carrying firewood,’ she added wistfully.

Thomas sat beside her and stared into the wet dusk, which was hazed by a small mist. He was not sure it really was St Gallus’s day for he had lost his reckoning while they travelled. Perhaps it was already St Audrey’s day? It was October, he knew that, and he knew that one thousand, three hundred and forty-six years had passed since Christ had been born, but he was not sure which day it was. It was easy to lose count. His father had once recited all the Sunday services on a Saturday and he had had to do them again the next day. Thomas surreptitiously made the sign of the cross. He was a priest’s bastard and that was said to bring bad luck. He shivered. There was a heaviness in the air that owed nothing to the setting sun nor to the rain clouds nor to the mist. God help us, he thought, but there was an evil in this dusk and he made the sign of the cross again and said a silent prayer to St Gallus and his obedient bear. There had been a dancing bear in London, its teeth nothing but rotted yellow stumps and its brown flanks matted with blood from its owner’s goad. The street dogs had snarled at it, slunk about it and shrank back when the bear swung on them.

‘How far to Durham?’ Eleanor asked, this time speaking French, her native language.

‘Tomorrow, I think,’ Thomas answered, still gazing north to where the heavy dark was shrouding the land. ‘She asked,’ he explained in English to Father Hobbe, ‘when we would reach Durham.’

‘Tomorrow, pray God,’ the priest said.

‘Tomorrow you can rest,’ Thomas promised Eleanor in French. She was pregnant with a child that, God willing, would be born in the springtime. Thomas was not sure how he felt about being a father. It seemed too early for him to become responsible, but Eleanor was happy and he liked to please her and so he told her he was happy as well. Some of the time, that was even true.

‘And tomorrow,’ Father Hobbe said, ‘we shall fetch our answers.’

‘Tomorrow,’ Thomas corrected him, ‘we shall ask our questions.’

‘God will not let us come this far to be disappointed,’ Father Hobbe said, and then, to keep Thomas from arguing, he laid out their meagre supper. ‘That’s all that’s left of the bread,’ he said, ‘and we should save some of the cheese and an apple for breakfast.’ He made the sign of the cross over the food, blessing it, then broke the hard bread into three pieces. ‘We should eat before nightfall.’

Darkness brought a brittle cold. A brief shower passed and after it the wind dropped. Thomas slept closest to the byre door and sometime after the wind died he woke because there was a light in the northern sky.

He rolled over, sat up and he forgot that he was cold, forgot his hunger, forgot all the small nagging discomforts of life, for he could see the Grail. The Holy Grail, the most precious of all Christ’s bequests to man, lost these thousand years and more, and he could see it glowing in the sky like shining blood and about it, bright as the glittering crown of a saint, rays of dazzling shimmer filled the heaven.

Thomas wanted to believe. He wanted the Grail to exist. He thought that if the Grail were to be found then all the world’s evil would be drained into its depths. He so wanted to believe and that October night he saw the Grail like a great burning cup in the north and his eyes filled with tears so that the image blurred, yet he could see it still, and it seemed to him that a vapour boiled from the holy vessel. Beyond it, in ranks rising to the heights of the air, were rows of angels, their wings touched by fire. All the northern sky was smoke and gold and scarlet, glowing in the night as a sign to doubting Thomas. ‘Oh, Lord,’ he said aloud and he threw off his blanket and knelt in the byre’s cold doorway, ‘oh, Lord.’

‘Thomas?’ Eleanor, beside him had awoken. She sat up and stared into the night. ‘Fire,’ she said in French, ‘c’est un grand incendie.’ Her voice was awed.

‘C’est un incendie?’ Thomas asked, then came fully awake and saw there was indeed a great fire on the horizon from where the flames boiled up to light a cup-shaped chasm in the clouds.

‘There is an army there,’ Eleanor whispered in French. ‘Look!’ She pointed to another glow, farther off. They had seen such lights in the sky in France, flamelight reflected from cloud where England’s army blazed its way across Normandy and Picardy.

Thomas still gazed north, but now in disappointment. It was an army? Not the Grail?

‘Thomas?’ Eleanor was worried.

‘It’s just rumour,’ he said. He was a priest’s bastard and he had been raised on the sacred scriptures and in Matthew’s Gospel it had been promised that at the end of time there would be battles and rumours of battles. The scriptures promised that the world would come to its finish in a welter of war and blood, and in the last village, where the folk had watched them suspiciously, a sullen priest had accused them of being Scottish spies. Father Hobbe had bridled at that, threatening to box his fellow priest’s ears, but Thomas had calmed both men down, and then spoken with a shepherd who said he had seen smoke in the northern hills. The Scots, the shepherd said, were marching south, though the priest’s woman scoffed at the tale, claiming that the Scottish troops were nothing but cattle raiders. ‘Bar your door at night,’ she advised, ‘and they’ll leave you alone.’

The far light subsided. It was not the Grail.

‘Thomas?’ Eleanor frowned at him.

‘I had a dream,’ he said, ‘just a dream.’

‘I felt the child move,’ she said, and she touched his shoulder. ‘Will you and I be married?’

‘In Durham,’ he promised her. He was a bastard and he wanted no child of his to carry the same taint. ‘We shall reach the city tomorrow,’ he reassured Eleanor, ‘and you and I will marry in a church and then we shall ask our questions.’ And, he prayed, let one of the answers be that the Grail did not exist. Let it be a dream, a mere trick of fire and cloud in a night sky, for else Thomas feared it would lead to madness. He wanted to abandon this search; he wanted to give up the Grail and return to being what he was and what he wanted to be: an archer of England.

Bernard de Taillebourg, Frenchman, Dominican friar and Inquisitor, spent the autumn night in a pig pen and when dawn came thick and white with fog, he went to his knees and thanked God for the privilege of sleeping in fouled straw. Then, mindful of his high task, he said a prayer to St Dominic, begging the saint to intercede with God to make this day’s work good. ‘As the flame in thy mouth lights us to truth’ – he spoke aloud – ‘so let it light our path to success.’ He rocked forward in the intensity of his emotion and his head struck against a rough stone pillar that supported one corner of the pen. Pain jabbed through his skull and he invited more by forcing his forehead back against the stone, grinding the skin until he felt the blood trickle down to his nose. ‘Blessed Dominic,’ he cried, ‘blessed Dominic! God be thanked for thy glory! Light our way!’ The blood was on his lips now and he licked it and reflected on all the pain that the saints and martyrs had endured for the Church. His hands were clasped and there was a smile on his haggard face.

Soldiers who, the night before, had burned much of the village to ash and raped the women who failed to escape and killed the men who tried to protect the women, now watched the priest drive his head repeatedly against the blood-spattered stone. ‘Dominic,’ Bernard de Taillebourg gasped, ‘oh, Dominic!’ Some of the soldiers made the sign of the cross for they recognized a holy man when they saw one. One or two even knelt, though it was awkward in their mail coats, but most just watched the priest warily, or else watched his servant who, sitting outside the sty, returned their gaze.

The servant, like Bernard de Taillebourg, was a Frenchman, but something in the younger man’s appearance suggested a more exotic birth. His skin was sallow, almost as dark as a Moor’s, and his long hair was sleekly black which, with his narrow face, gave him a feral look. He wore mail and a sword and, though he was nothing but a priest’s servant, he carried himself with confidence and dignity. His dress was elegant, something strange in this ragged army. No one knew his name. No one even wanted to ask, just as no one wanted to ask why he never ate or chatted with the other servants, but kept himself fastidiously apart. Now the mysterious servant watched the soldiers and in his left hand he held a knife with a very long and thin blade, and once he knew enough men were looking at him, he balanced the knife on an outstretched finger. The knife was poised on its sharp tip, which was prevented from piercing the servant’s skin by the cut-off finger of a mail glove that he wore like a sheath. Then he jerked the finger and the knife span in the air, blade glittering, to come down, tip first, to balance on his finger again. The servant had not looked at the knife once, but kept his dark-eyed gaze fixed on the soldiers. The priest, oblivious to the display, was howling prayers, his thin cheeks laced with blood. ‘Dominic! Dominic! Light our path!’ The knife span again, its wicked blade catching the foggy morning’s small light. ‘Dominic! Guide us! Guide us!’

‘On your horses! Mount up! Move yourselves!’ A grey-haired man, a big shield slung from his left shoulder, pushed through the onlookers. ‘We’ve not got all day! What in the name of the devil are you all gawking at? Jesus Christ on His goddamn cross, what is this, Eskdale bloody fair? For Christ’s sake, move! Move!’ The shield on his shoulder was blazoned with the badge of a red heart, but the paint was so faded and the shield’s leather cover so scarred that the badge was hard to distinguish. ‘Oh, suffering Christ!’ The man had spotted the Dominican and his servant. ‘Father! We’re going now. Right now! And I don’t wait for prayers.’ He turned back to his men. ‘Mount up! Move your bones! There’s devil’s work to be done!’

‘Douglas!’ the Dominican snapped.

The grey-haired man turned back fast. ‘My name, priest, is Sir William, and you’ll do well to remember it.’

The priest blinked. He seemed to be suffering a momentary confusion, still caught up in the ecstasy of his pain-driven prayer, then he gave a perfunctory bow as if acknowledging his fault in using Sir William’s surname. ‘I was talking to the blessed Dominic,’ he explained.

‘Aye, well, I hope you asked him to shift this damn fog?’

‘And he will lead us today! He will guide us!’

‘Then he’d best get his damn boots on,’ Sir William Douglas, Knight of Liddesdale, growled at the priest, ‘for we’re leaving whether your saint is ready or not.’ Sir William’s chain mail was battle-torn and patched with newer rings. Rust showed at the hem and at the elbows. His faded shield, like his weather-beaten face, was scarred. He was forty-six now and he reckoned he had a sword, arrow or spear scar for each of those years that had turned his hair and short beard white. Now he pulled open the sty’s heavy gate. ‘On your trotters, father. I’ve a horse for you.’

‘I shall walk,’ Bernard de Taillebourg said, picking up a stout staff with a leather thong threaded through its tip, ‘as our Lord walked.’

‘Then you’ll not get wet crossing the streams, eh, is that it?’ Sir William chuckled. ‘You’ll walk on water will you, father? You and your servant?’ Alone among his men he did not seem impressed by the French priest or wary of the priest’s well-armed servant, but Sir William Douglas was famously unafraid of any man. He was a border chieftain who employed murder, fire, sword and lance to protect his land and some fierce priest from Paris was hardly likely to impress him. Sir William, indeed, was not overfond of priests, but his King had ordered him to take Bernard de Taillebourg on this morning’s raid and Sir William had grudgingly consented.

All around him soldiers pulled themselves into their saddles. They were lightly armed for they expected to meet no enemies. A few, like Sir William, carried shields, but most were content with just a sword. Bernard de Taillebourg, his friar’s robes mud-spattered and damp, hurried alongside Sir William. ‘Will you go into the city?’

‘Of course I’ll not go into the bloody city. There’s a truce, remember?’

‘But if there’s a truce …’

‘If there’s a bloody truce then we leave them be.’

The French priest’s English was good, but it took him a few moments to work out what Sir William’s last three words had meant. ‘There’ll be no fighting?’

‘Not between us and the city, no. And there’s no goddamned English army within a hundred miles so there’ll be no fighting. All we’re doing is looking for food and forage, father, food and forage. Feed your men and feed your animals and that’s the way to win your wars.’ Sir William, as he spoke, climbed onto his horse, which was held by a squire. He pushed his boots into the stirrups, plucked the skirts of his mail coat from under his thighs and gathered the reins. ‘I’ll get you close to the city, father, but after that you’ll have to shift for yourself.’

‘Shift?’ Bernard de Taillebourg asked, but Sir William had already turned away and spurred his horse down a muddy lane that ran between low stone walls. Two hundred mounted men-at-arms, grim and grey on this foggy morning, streamed after him, and the priest, buffeted by their big dirty horses, struggled to keep up. The servant followed with apparent unconcern. He was evidently accustomed to being among soldiers and showed no apprehension, indeed his demeanour suggested he might be better with his weapons than most of the men who rode behind Sir William.

The Dominican and his servant had travelled to Scotland with a dozen other messengers sent to King David II by Philip of Valois, King of France. The embassy had been a cry for help. The English had burned their way across Normandy and Picardy, they had slaughtered the French King’s army near a village called Crécy and their archers now held a dozen fastnesses in Brittany while their savage horsemen rode from Edward of England’s ancestral possessions in Gascony. All that was bad, but even worse, and as if to show all Europe that France could be dismembered with impunity, the English King was now laying siege to the great fortress harbour of Calais. Philip of Valois was doing his best to raise the siege, but winter was coming, his nobles grumbled that their King was no warrior, and so he had appealed for aid to Scotland’s King David, son of Robert the Bruce. Invade England, the French King had pleaded, and thus force Edward to abandon the siege of Calais to protect his homeland. The Scots had pondered the invitation, then were persuaded by the French King’s embassy that England lay defenceless. How could it be otherwise? Edward of England’s army was all at Calais or else in Brittany or Gascony, and there was no one left to defend England, and that meant the old enemy was helpless, it was asking to be raped and all the riches of England were just waiting to fall into Scottish hands.

And so the Scots had come south.

It was the largest army that Scotland had ever sent across the border. The great lords were all there, the sons and grandsons of the warriors who had humbled England in the bloody slaughter about the Bannockburn, and those lords had brought their men-at-arms who had grown hard with incessant frontier battles, but this time, smelling plunder, they were accompanied by the clan chiefs from the mountains and islands: chiefs leading wild tribesmen who spoke a language of their own and fought like devils unleashed. They had come in their thousands to make themselves rich and the French messengers, their duty done, had sailed home to tell Philip of Valois that Edward of England would surely raise his siege of Calais when he learned that the Scots were ravaging his northern lands.

The French embassy had sailed for home, but Bernard de Taillebourg had stayed. He had business in northern England, but in the first days of the invasion he had experienced nothing except frustration. The Scottish army was twelve thousand strong, larger than the army with which Edward of England had defeated the French at Crécy, yet once across the frontier the great army had stopped to besiege a lonely fortress garrisoned by a mere thirty-eight men, and though the thirty-eight had all died, it had wasted four days. More time was spent negotiating with the citizens of Carlisle who had paid gold to have their city spared, and then the young Scottish King frittered away three more days pillaging the great priory of the Black Canons at Hexham. Now, ten days after they had crossed the frontier, and after wandering across the northern English moors, the Scottish army had at last reached Durham. The city had offered a thousand golden pounds if they could be spared and King David had given them two days to raise the money. Which meant that Bernard de Taillebourg had two days to find a way to enter the city, to which end, slipping in the mud and half blinded by the fog, he followed Sir William Douglas into a valley, across a stream and up a steep hill. ‘Which way is the city?’ he demanded of Sir William.

‘When the fog lifts, father, I’ll tell you.’

‘They’ll respect the truce?’

‘They’re holy men in Durham, father,’ Sir William answered wryly, ‘but better still, they’re frightened men.’ It had been the monks of the city who had negotiated the ransom and Sir William had advised against acceptance. If monks offered a thousand pounds, he reckoned, then it would have been better to have killed the monks and taken two thousand, but King David had overruled him. David the Bruce had spent much of his youth in France and so considered himself cultured, but Sir William was not thus hampered by scruples. ‘You’ll be safe if you can talk your way into the city,’ Sir William reassured the priest.

The horsemen had reached the hilltop and Sir William turned south along the ridge, still following a track that was edged with stone walls and which led, after a mile or so, to a deserted hamlet where four cottages, so low that their shaggy thatched roofs seemed to swell out of the straggling turf, clustered by a crossroads. In the centre of the crossroads, where the muddy ruts surrounded a patch of nettles and grass, a stone cross leaned southwards. Sir William curbed his horse beside the monument and stared at the carved dragon encircling the shaft. The cross was missing one arm. A dozen of his men dismounted and ducked into the low cottages, but they found no one and nothing, though in one cottage the embers of a fire still glowed and so they used the smouldering wood to fire the four thatched roofs. The thatch was reluctant to catch the fire for it was so damp that mushrooms grew on the mossy straw.