Полная версия:

Sword Song

SWORD SONG

BERNARD CORNWELL

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2007

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 2007

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Photography by Steffan Hill © Carnival Film & Television Limited 2017

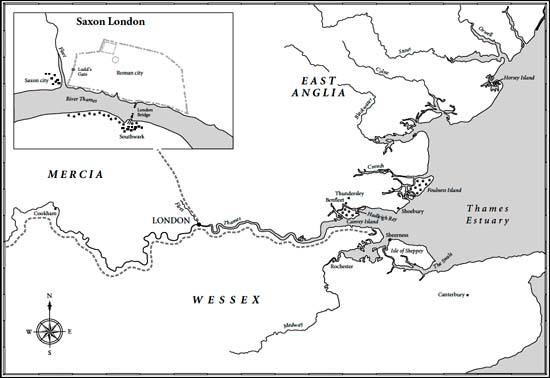

Map © John Gilkes 2007

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007219735

Ebook Edition © December 2010 ISBN: 9780007279654

Version: 2017-05-05

SWORD SONG

is voor Aukje,

mit liefde:

Er was eens …

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Place-names

Map

Prologue

Part One: THE BRIDE

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Part Two: THE CITY

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Part Three: THE SCOURING

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Historical Note

About the Author

Also by Bernard Cornwell

About the Publisher

PLACE-NAMES

The spelling of place names in Anglo Saxon England was an uncertain business, with no consistency and no agreement even about the name itself. Thus London was variously rendered as Lundonia, Lundenberg, Lundenne, Lundene, Lundenwic, Lundenceaster and Lundres. Doubtless some readers will prefer other versions of the names listed below, but I have usually employed whichever spelling is cited in either the Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names or the Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names for the years nearest or contained within Alfred’s reign, AD 871–899, but even that solution is not foolproof. Hayling Island, in 956, was written as both Heilincigae and Hæglingaiggæ. Nor have I been consistent myself; I should spell England as Englaland, and have preferred the modern form Northumbria to Norðhymbralond to avoid the suggestion that the boundaries of the ancient kingdom coincide with those of the modern county. So this list, like the spellings themselves, is capricious.

Æscengum Eashing, Surrey Arwan River Orwell, Suffolk Beamfleot Benfleet, Essex Bebbanburg Bamburgh, Northumberland Berrocscire Berkshire Cair Ligualid Carlisle, Cumbria Caninga Canvey Island, Essex Cent Kent Cippanhamm Chippenham, Wiltshire Cirrenceastre Cirencester, Gloucestershire Cisseceastre Chichester, Sussex Coccham Cookham, Berkshire Colaun, River River Colne, Essex Contwaraburg Canterbury, Kent Cornwalum Cornwall Cracgelad Cricklade, Wiltshire Dunastopol Dunstable (Roman name Durocobrivis), Bedfordshire Dunholm Durham, County Durham Eoferwic York, Yorkshire Ethandun Edington, Wiltshire Exanceaster Exeter, Devon Fleot River Fleet, London Frankia Germany Fughelness Foulness Island, Essex Grantaceaster Cambridge, Cambridgeshire Gyruum Jarrow, County Durham Hastengas Hastings, Sussex Horseg Horsey Island, Essex Hothlege River Hadleigh, Essex Hrofeceastre Rochester, Kent Hwealf River Crouch, Essex Lundene London Mæides Stana Maidstone, Kent Medwæg River Medway, Kent Oxnaforda Oxford, Oxfordshire Padintune Paddington, Greater London Pant River Blackwater, Essex Scaepege Isle of Sheppey, Kent Sceaftes Eye Sashes Island (at Coccham) Sceobyrig Shoebury, Essex Scerhnesse Sheerness, Kent Sture River Stour, Essex Sutherge Surrey Suthriganaweorc Southwark, Greater London Swealwe River Swale, Kent Temes River Thames Thunresleam Thundersley, Essex Wæced Watchet, Somerset Wæclingastræt Watling Street Welengaford Wallingford, Oxfordshire Werham Wareham, Dorset Wiltunscir Wiltshire Wintanceaster Winchester, Hampshire Wocca’s Dun South Ockenden, Essex Wodenes Eye Odney Island (at Coccham)

PROLOGUE

Darkness. Winter. A night of frost and no moon.

We floated on the River Temes, and beyond the boat’s high bow I could see the stars reflected on the shimmering water. The river was in spate as melted snow fed it from countless hills. The winterbournes were flowing from the chalk uplands of Wessex. In summer those streams would be dry, but now they foamed down the long green hills and filled the river and flowed to the distant sea.

Our boat, which had no name, lay close to the Wessex bank. North across the river lay Mercia. Our bows pointed upstream. We were hidden beneath the leafless, bending branches of three willow trees, held there against the current by a leather mooring rope tied to one of those branches.

There were thirty-eight of us in that nameless boat, which was a trading ship that worked the upper reaches of the Temes. The ship’s master was called Ralla and he stood beside me with one hand on the steering-oar. I could hardly see him in the darkness, but knew he wore a leather jerkin and had a sword at his side. The rest of us were in leather and mail, had helmets and carried shields, axes, swords or spears. Tonight we would kill.

Sihtric, my servant, squatted beside me and stroked a whetstone along the blade of his short-sword. ‘She says she loves me,’ he told me.

‘Of course she says that,’ I said.

He paused, and when he spoke again his voice had brightened, as though he had been encouraged by my words. ‘And I must be nineteen by now, lord! Maybe even twenty?’

‘Eighteen?’ I suggested.

‘I could have been married four years ago, lord!’

We spoke almost in whispers. The night was full of noises. The water rippled, the bare branches clattered in the wind, a night creature splashed into the river, a vixen howled like a dying soul, and somewhere an owl hooted. The boat creaked. Sihtric’s stone hissed and scraped on the steel. A shield thumped against a rower’s bench. I dared not speak louder, despite the night’s noises, because the enemy ship was upstream of us and the men who had gone ashore from that ship would have left sentries on board. Those sentries might have seen us as we slipped downstream on the Mercian bank, but by now they would surely have thought we were long gone towards Lundene.

‘But why marry a whore?’ I asked Sihtric.

‘She’s …’ Sihtric began.

‘She’s old,’ I snarled, ‘maybe thirty. And she’s addled. Ealhswith only has to see a man and her thighs fly apart! If you lined up every man who’d tupped that whore you’d have an army big enough to conquer all Britain.’ Beside me Ralla sniggered. ‘You’d be in that army, Ralla?’ I asked.

‘Twenty times over, lord,’ the shipmaster said.

‘She loves me,’ Sihtric spoke sullenly.

‘She loves your silver,’ I said, ‘and besides, why put a new sword in an old scabbard?’

It is strange what men talk about before battle. Anything except what faces them. I have stood in a shield wall, staring at an enemy bright with blades and dark with menace, and heard two of my men argue furiously about which tavern brewed the best ale. Fear hovers in the air like a cloud and we talk of nothing to pretend that the cloud is not there.

‘Look for something ripe and young,’ I advised Sihtric. ‘That potter’s daughter is ready to wed. She must be thirteen.’

‘She’s stupid,’ Sihtric objected.

‘And what are you, then?’ I demanded. ‘I give you silver and you pour it into the nearest open hole! Last time I saw her she was wearing an arm ring I gave you.’

He sniffed, said nothing. His father had been Kjartan the Cruel, a Dane who had whelped Sihtric on one of his Saxon slaves. Yet Sihtric was a good boy, though in truth he was no longer a boy. He was a man who had stood in the shield wall. A man who had killed. A man who would kill again tonight. ‘I’ll find you a wife,’ I promised him.

It was then we heard the screaming. It was faint because it came from very far off, a mere scratching noise in the darkness that told of pain and death to our south. There were screams and shouting. Women were screaming and doubtless men were dying.

‘God damn them,’ Ralla said bitterly.

‘That’s our job,’ I said curtly.

‘We should …’ Ralla started, then thought better of speaking. I knew what he was going to say, that we should have gone to the village and protected it, but he knew what I would have answered.

I would have told him that we did not know which village the Danes were going to attack, and even if I had known I would not have protected it. We might have shielded the place if we had known where the attackers were going. I could have placed all my household troops in the small houses and, the moment the raiders came, erupted into the street with sword, axe and spear, and we would have killed some of them, but in the dark many more would have escaped and I did not want one to escape. I wanted every Dane, every Norseman, every raider dead. All of them, except one, and that one I would send eastwards to tell the Viking camps on the banks of the Temes that Uhtred of Bebbanburg was waiting for them.

‘Poor souls,’ Ralla muttered. To the south, through the tangle of black branches, I could see a red glow that betrayed burning thatch. The glow spread and grew brighter to lighten the winter sky beyond a row of coppiced trees. The glow reflected off my men’s helmets, giving their metal a sheen of red, and I called for them to take the helmets off in case the enemy sentries in the large ship ahead saw the reflected glimmer.

I took off my own helmet with its silver wolf crest.

I am Uhtred, Lord of Bebbanburg, and in those days I was a lord of war. I stood there in mail and leather, cloaked and armed, young and strong. I had half my household troops in Ralla’s ship while the other half were somewhere to the west, mounted on horses and under Finan’s command.

Or I hoped they were waiting in the night-shrouded west. We in the ship had enjoyed the easier task, for we had slid down the dark river to find the enemy, while Finan had been forced to lead his men across night-black country. But I trusted Finan. He would be there, fidgeting, grimacing, waiting to unleash his sword.

This was not our first attempt in that long wet winter to set an ambush on the Temes, but it was the first that promised success. Twice before I had been told that Vikings had come through the gap in Lundene’s broken bridge to raid the soft, plump villages of Wessex, and both times we had come downriver and found nothing. But this time we had trapped the wolves. I touched the hilt of Serpent-Breath, my sword, then touched the amulet of Thor’s hammer that hung around my neck.

Kill them all, I prayed to Thor, kill them all but one.

It must have been cold in that long night. Ice skimmed the dips in the fields where the river had flooded, but I do not remember the cold. I remember the anticipation. I touched Serpent-Breath again and it seemed to me that she quivered. I sometimes thought that blade sang. It was a thin, half-heard song, a keening noise, the song of the blade wanting blood; the sword song.

We waited and, afterwards, when it was all over, Ralla told me I had never stopped smiling.

I thought our ambush would fail, for the raiders did not return to their ship till dawn blazed light across the east. Their sentries, I thought, must surely see us, but they did not. The drooping willow boughs served as a flimsy screen, or perhaps the rising winter sun dazzled them because no one saw us.

We saw them. We saw the mail-clad men herding a crowd of women and children across a rain-flooded pasture. I guessed there were fifty raiders and they had as many captives. The women would be the young ones from the burned village, and they had been taken for the raiders’ pleasure. The children would go to the slave market in Lundene and from there across the sea to Frankia or even beyond. The women, once they had been used, would also be sold. We were not so close that we could hear the prisoners sobbing, but I imagined it. To the south, where low green hills swelled from the river’s plain, a great drift of smoke dirtied the clear winter sky to mark where the raiders had burned the village.

Ralla stirred. ‘Wait,’ I murmured, and Ralla went still. He was a grizzled man, ten years older than I, with eyes reduced to slits from the long years of staring across sun-reflecting seas. He was a shipmaster, soldier and friend. ‘Not yet,’ I said softly, and touched Serpent-Breath and felt the quiver in the steel.

Men’s voices were loud, relaxed and laughing. They shouted as they pushed their prisoners into the ship. They forced them to crouch in the cold flooded bilge so that the overloaded craft would be stable for its voyage through the downriver shallows, where the Temes raced across stone ledges and only the best and bravest shipmasters knew the channel. Then the warriors clambered aboard themselves. They took their plunder with them, the spits and cauldrons and ard-blades and knives and whatever else could be sold or melted or used. Their laughter was raucous. They were men who had slaughtered, and who would become rich on their prisoners and they were in a cheerful, careless mood.

And Serpent-Breath sang soft in her scabbard.

I heard the clatter from the other ship as the oars were thrust into their rowlocks. A voice called out a command. ‘Push off!’

The great beak of the enemy ship, crowned with a monster’s painted head, turned out into the river. Men shoved oar-blades against the bank, pushing the boat farther out. The ship was already moving, carried towards us by the spate-driven current. Ralla looked at me.

‘Now,’ I said. ‘Cut the line!’ I called, and Cerdic, in our bows, slashed through the leather rope tethering us to the willow. We were only using twelve oars and those now bit into the river as I pushed my way forward between the rowers’ benches. ‘We kill them all!’ I shouted. ‘We kill them all!’

‘Pull!’ Ralla roared, and the twelve men heaved on their oars to fight the river’s power.

‘We kill every last bastard!’ I shouted as I climbed onto the small bow platform where my shield waited. ‘Kill them all! Kill them all!’ I put on my helmet, then pushed my left forearm through the shield loops, hefted the heavy wood, and slid Serpent-Breath from her fleece-lined scabbard. She did not sing now. She screamed.

‘Kill!’ I shouted. ‘Kill, kill, kill!’ and the oars bit in time to my shouting. Ahead of us the enemy ship slewed in the river as panicked men missed their stroke. They were shouting, looking for shields, scrambling over the benches where a few men still tried to row. Women screamed and men tripped each other.

‘Pull!’ Ralla shouted. Our nameless ship surged into the current as the enemy was swept towards us. Her monster’s head had a tongue painted red, white eyes, teeth like daggers.

‘Now!’ I called to Cerdic and he threw the grapnel with its chain so that it caught on the enemy ship’s bow and he hauled on the chain to sink the grapnel’s teeth into the ship’s timber and so draw her closer.

‘Now kill!’ I shouted, and leaped across the gap.

Oh the joy of being young. Of being twenty-eight years old, of being strong, of being a lord of war. All gone now, just memory is left, and memories fade. But the joy is bedded in the memory.

Serpent-Breath’s first stroke was a back-cut. I made it as I landed on the enemy’s bow platform where a man was trying to tug the grapnel free, and Serpent-Breath took him in the throat with a cut so fast and hard that it half severed his head. His whole skull flopped backwards as blood brightened the winter day. Blood splashed on my face. I was death come from the morning, blood-spattered death in mail and black cloak and wolf-crested helmet.

I am old now. So old. My sight fades, my muscles are weak, my piss dribbles, my bones ache and I sit in the sun and fall asleep to wake tired. But I remember those fights, those old fights. My newest wife, as pious a piece of stupid woman who ever whined, flinches when I tell the stories, but what else do the old have, but stories? She protested once, saying she did not want to know about heads flopping backwards in bright spraying blood, but how else are we to prepare our young for the wars they must fight? I have fought all my life. That was my fate, the fate of us all. Alfred wanted peace, but peace fled from him and the Danes came and the Norsemen came, and he had no choice but to fight. And when Alfred was dead and his kingdom was powerful, more Danes came, and more Norsemen, and the Britons came from Wales and the Scots howled down from the north, and what can a man do but fight for his land, his family, his home and his country? I look at my children and at their children and at their children’s children and I know they will have to fight, and that so long as there is a family named Uhtred, and so long as there is a kingdom on this windswept island, there will be war. So we cannot flinch from war. We cannot hide from its cruelty, its blood, its stench, its vileness or its joy, because war will come to us whether we want it or not. War is fate, and wyrd bið ful ãræd. Fate is inescapable.

So I tell these stories so that my children’s children will know their fate. My wife whimpers, but I make her listen. I tell her how our ship crashed into the enemy’s outside flank, and how the impact drove that other ship’s bows towards the southern bank. That was what I had wanted, and Ralla had achieved it perfectly. Now he scraped his ship down the enemy’s hull, our impetus snapping the Dane’s forward oars as my men jumped aboard, swords and axes swinging. I had staggered after that first cut, but the dead man had fallen off the platform to impede two others trying to reach me, and I shouted a challenge as I leaped down to face them. Serpent-Breath was lethal. She was, she is, a lovely blade, forged in the north by a Saxon smith who had known his trade. He had taken seven rods, four of iron and three of steel, and he had heated them and hammered them into one long two-edged blade with a leaf-shaped point. The four softer iron rods had been twisted in the fire and those twists survived in the blade as ghostly wisps of pattern that looked like the curling flame-breath of a dragon, and that was how Serpent-Breath had gained her name.

A bristle-bearded man swung an axe at me that I met with my out-thrust shield and slid the dragon-wisps into his belly. I gave a fierce twist with my right hand so that his dying flesh and guts did not grip the blade, then I yanked her out, more blood flying, and dragged the axe-impaled shield across my body to parry a sword cut. Sihtric was beside me, driving his short-sword up into my newest attacker’s groin. The man screamed. I think I was shouting. More and more of my men were aboard now, swords and axes glinting. Children cried, women wailed, raiders died.