Полная версия:

Stonehenge: A Novel of 2000 BC

BERNARD CORNWELL

Stonehenge

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1999

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 1999

Illustrations by Rex Nicholls

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007550890

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2011 ISBN: 9780007338771

Version: 2017-05-06

Dedication

In memory of

BILL MOIR

1943–1998

‘The Druid’s groves are gone – so much the better:

Stonehenge is not – but what the Devil is it?’

Lord Byron, Don Juan

Canto XI, verse XXV.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One: The Sky Temple

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Part Two: The Temple of Shadows

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Part Three: The Temple of the Dead

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Historical Note

Chapter 21

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by Bernard Cornwell

About the Publisher

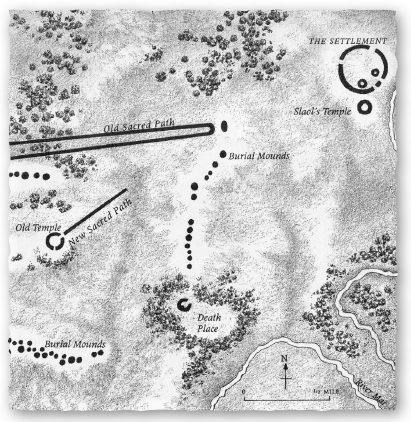

Map of the settlement and temples of Ratharryn, c. 2000 BC

The gods talk by signs. It may be a leaf falling in summer, the cry of a dying beast or the ripple of wind on calm water. It might be smoke lying close to the ground, a rift in the clouds or the flight of a bird.

But on that day the gods sent a storm. It was a great storm, a storm that would be remembered, though folk did not name the year by that storm. Instead they called it the Year the Stranger Came.

For a stranger came to Ratharryn on the day of the storm. It was a summer’s day, the same day that Saban was almost murdered by his half-brother.

The gods were not talking that day. They were screaming.

Saban, like all children, went naked in summer. He was six years younger than his half-brother, Lengar, and, because he had not yet passed the trials of manhood, he bore no tribal scars or killing marks. But his time of trial was only a year away, and their father had instructed Lengar to take Saban into the forest and teach him where the stags could be found, where the wild boars lurked and where the wolves had their dens. Lengar had resented the duty and so, instead of teaching his brother, he dragged Saban through thickets of thorn so that the boy’s sun-darkened skin was bleeding. ‘You’ll never become a man,’ Lengar jeered.

Saban, sensibly, said nothing.

Lengar had been a man for five years and had the blue scars of the tribe on his chest and the marks of a hunter and a warrior on his arms. He carried a longbow made of yew, tipped with horn, strung with sinew and polished with pork fat. His tunic was of wolfskin and his long black hair was braided and tied with a strip of fox’s fur. He was tall, had a narrow face and was reckoned one of the tribe’s great hunters. His name meant Wolf Eyes, for his gaze had a yellowish tinge. He had been given another name at birth, but like many in the tribe he had taken a new name at manhood.

Saban was also tall and had long black hair. His name meant Favoured One, and many in the tribe thought it apt for, even at a mere twelve summers, Saban promised to be handsome. He was strong and lithe, he worked hard and he smiled often. Lengar rarely smiled. ‘He has a cloud in his face,’ the women said of him, but not within his hearing, for Lengar was likely to be the tribe’s next chief. Lengar and Saban were sons of Hengall, and Hengall was chief of the people of Ratharryn.

All that long day Lengar led Saban through the forest. They met no deer, no boars, no wolves, no aurochs and no bears. They just walked and in the afternoon they came to the edge of the high ground and saw that all the land to the west was shadowed by a mass of black cloud. Lightning flickered the dark cloud pale, twisted to the far forest and left the sky burned. Lengar squatted, one hand on his polished bow, and watched the approaching storm. He should have started for home, but he wanted to worry Saban and so he pretended he did not care about the storm god’s threat.

It was while they watched the storm that the stranger came.

He rode a small dun horse that was white with sweat. His saddle was a folded woollen blanket and his reins were lines of woven nettle fibre, though he hardly needed them for he was wounded and seemed tired, letting the small horse pick its own way up the track which climbed the steep escarpment. The stranger’s head was bowed and his heels hung almost to the ground. He wore a woollen cloak dyed blue and in his right hand was a bow while on his left shoulder there hung a leather quiver filled with arrows fledged with the feathers of seagulls and crows. His short beard was black, while the tribal marks scarred into his cheeks were grey.

Lengar hissed at Saban to stay silent, then tracked the stranger eastwards. Lengar had an arrow on his bowstring, but the stranger never once turned to see if he was being followed and Lengar was content to let the arrow rest on its string. Saban wondered if the horseman even lived, for he seemed like a dead man slumped inert on his horse’s back.

The stranger was an Outlander. Even Saban knew that, for only the Outfolk rode the small shaggy horses and had grey scars on their faces. The Outfolk were enemy, yet still Lengar did not release his arrow. He just followed the horseman and Saban followed Lengar until at last the Outlander came to the edge of the trees where bracken grew. There the stranger stopped his horse and raised his head to stare across the gently rising land while Lengar and Saban crouched unseen behind him.

The stranger saw bracken and, beyond it, where the soil was thin above the underlying chalk, grassland. There were grave mounds dotted on the grassland’s low crest. Pigs rooted in the bracken while white cattle grazed the pastureland. The sun still shone here. The stranger stayed a long while at the wood’s edge, looking for enemies, but seeing none. Off to his north, a long way off, there were wheatfields fenced with thorn over which the first clouds, outriders of the storm, were chasing their shadows, but all ahead of him was sunlit. There was life ahead, darkness behind, and the small horse, unbidden, suddenly jolted into the bracken. The rider let it carry him.

The horse climbed the gentle slope to the grave mounds. Lengar and Saban waited until the stranger had disappeared over the skyline, then followed and, once at the crest, they crouched in a grave’s ditch and saw that the rider had stopped beside the Old Temple.

A grumble of thunder sounded and another gust of wind flattened the grass where the cattle grazed. The stranger slid from his horse’s back, crossed the overgrown ditch of the Old Temple and disappeared into the hazel shrub that grew so thick within the sacred circle. Saban guessed the man was seeking sanctuary.

But Lengar was behind the Outlander, and Lengar was not given to mercy.

The abandoned horse, frightened by the thunder and by the big cattle, trotted west towards the forest. Lengar waited until the horse had gone back into the trees, then rose from the ditch and ran towards the hazels where the stranger had gone.

Saban followed, going to where he had never been in all his twelve years.

To the Old Temple.

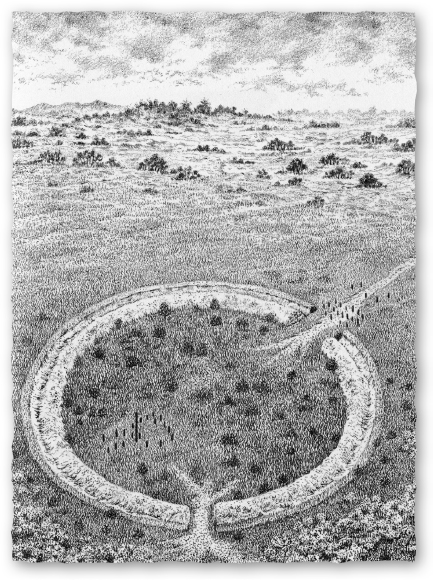

Once, many years before, so long before that no one alive could remember those times, the Old Temple had been the greatest shrine of the heartland. In those days, when men had come from far off to dance the temple’s rings, the high bank of chalk that encircled the shrine had been so white that it seemed to shine in the moonlight. From one side of the shining ring to the other was a hundred paces, and in the old days that sacred space had been beaten bare by the feet of the dancers as they girdled the death house that had been made from three rings of trimmed oak trunks. The smooth bare trunks had been oiled with animal fat and hung with boughs of holly and ivy.

Now the bank was thick with grass and choked by weeds. Small hazels grew in the ditch and more hazels had invaded the wide space inside the circular bank so that, from a distance, the temple looked like a grove of small shrubs. Birds nested where men had once danced. One oak pole of the death house still showed above the tangled hazels, but the pole was leaning now and its once smooth wood was pitted, black and thick with fungi.

The temple had been abandoned, yet the gods do not forget their shrines. Sometimes, on still days when a mist lay on the pasture, or when the swollen moon hung motionless above the chalk ring, the hazel leaves shivered as though a wind passed through them. The dancers were gone, but the power remained.

And now the Outlander had gone to the temple.

The gods were screaming.

Cloud shadow swallowed the pasture as Lengar and Saban ran towards the Old Temple. Saban was cold and he was scared. Lengar was also frightened, but the Outfolk were famous for their wealth, and Lengar’s greed overcame his fear of entering the temple.

The stranger had clambered through the ditch and up the bank, but Lengar went to the old southern entrance where a narrow causeway led into the overgrown interior. Once across the causeway Lengar dropped onto all fours and crawled through the hazels. Saban followed reluctantly, not wanting to be left alone in the pasture when the storm god’s anger broke.

To Lengar’s surprise the Old Temple was not entirely overgrown for there was a cleared space where the death house had stood. Someone in the tribe must still visit the Old Temple, for the weeds had been cleared, the grass cut with a knife and a single ox-skull lay in the death house where the stranger now sat with his back against the one remaining temple post. The man’s face was pale and his eyes were closed, but his chest rose and fell with his laboured breathing. He wore a strip of dark stone inside his left wrist, fastened there by leather laces. There was blood on his woollen trews. The man had dropped his short bow and his quiver of arrows beside the ox-skull, and now clutched a leather bag to his wounded belly. He had been ambushed in the forest three days before. He had not seen his attackers, just felt the sudden hot pain of the thrown spear, then kicked his horse and let it carry him out of danger.

‘I’ll fetch father,’ Saban whispered.

‘You won’t,’ Lengar hissed, and the wounded man must have heard them for he opened his eyes and grimaced as he leaned forward to pick up his bow. But the stranger was slowed by pain, and Lengar was much faster. He dropped his longbow, scrambled from his hiding place and ran across the death house, scooping up the stranger’s bow with one hand and his quiver with the other. In his hurry he spilled the arrows so that there was only one left in the leather quiver.

A murmur of thunder sounded from the west. Saban shivered, fearing that the sound would swell to fill the air with the god’s rage, but the thunder faded, leaving the sky deathly still.

‘Sannas,’ the stranger said, then added some words in a tongue that neither Lengar nor Saban spoke.

‘Sannas?’ Lengar asked.

‘Sannas,’ the man repeated eagerly. Sannas was the great sorceress of Cathallo, famous throughout the land, and Saban presumed the stranger wanted to be healed by her.

Lengar smiled. ‘Sannas is not of our people,’ he said. ‘Sannas lives north of here.’

The stranger did not understand what Lengar said. ‘Erek,’ he said, and Saban, still watching from the undergrowth, wondered if that was the stranger’s name, or perhaps the name of his god. ‘Erek,’ the wounded man said more firmly, but the word meant nothing to Lengar who had taken the one arrow from the stranger’s quiver and fitted it onto the short bow. The bow was made of strips of wood and antler, glued together and bound with sinew, and Lengar’s people had never used such a weapon. They favoured the longer bow carved from the yew tree, but Lengar was curious about the odd weapon. He stretched the string, testing its strength.

‘Erek!’ the stranger cried loudly.

‘You’re Outfolk,’ Lengar said. ‘You have no business here.’ He stretched the bow again, surprised by the tension in the short weapon.

‘Bring me a healer. Bring me Sannas,’ the stranger said in his own tongue.

‘If Sannas were here,’ Lengar said, recognizing only that name, ‘I would kill her first.’ He spat. ‘That is what I think of Sannas. She is a shrivelled old bitch-cow, a husk of evil, toad-dung made flesh.’ He spat again.

The stranger leaned forward and laboriously scooped up the arrows that had spilled from his quiver and formed them into a small sheaf that he held like a knife as though to defend himself. ‘Bring me a healer,’ he pleaded in his own language. Thunder growled to the west, and the hazel leaves shuddered as a breath of cold wind gusted ahead of the approaching storm. The stranger looked again into Lengar’s eyes and saw no pity there. There was only the delight that Lengar took from death. ‘No,’ he said, ‘no, please, no.’

Lengar loosed the arrow. He was only five paces from the stranger and the small arrow struck its target with a sickening force, lurching the man onto his side. The arrow sank deep, leaving only a hand’s-breadth of its black-and-white feathered shaft showing at the left side of the stranger’s chest. Saban thought the Outlander must be dead because he did not move for a long time, but then the carefully made sheaf of arrows spilled from his hand as, slowly, very slowly, he pushed himself back upright. ‘Please,’ he said quietly.

‘Lengar!’ Saban scrambled from the hazels. ‘Let me fetch father!’

‘Quiet!’ Lengar had taken one of his own black-feathered arrows from its quiver and placed it on the short bowstring. He walked towards Saban, aiming the bow at him and grinning when he saw the terror on his half-brother’s face.

The stranger also stared at Saban, seeing a tall good-looking boy with tangled black hair and bright anxious eyes. ‘Sannas,’ the stranger begged Saban, ‘take me to Sannas.’

‘Sannas doesn’t live here,’ Saban said, understanding only the sorceress’s name.

‘We live here,’ Lengar announced, now pointing his arrow at the stranger, ‘and you’re an Outlander and you steal our cattle, enslave our women and cheat our traders.’ He let the second arrow loose and, like the first, it thumped into the stranger’s chest, though this time into the ribs on his right side. Again the man was jerked aside, but once again he forced himself upright as though his spirit refused to leave his wounded body.

‘I can give you power,’ he said, as a trickle of bubbly pink blood spilled from his mouth and into his short beard. ‘Power,’ he whispered.

But Lengar did not understand the man’s tongue. He had shot two arrows and still the man refused to die, so Lengar picked up his own longbow, laid an arrow on its string, and faced the stranger. He drew the huge bow back.

The stranger shook his head, but he knew his fate now and he stared Lengar in the eyes to show he was not afraid to die. He cursed his killer, though he doubted the gods would listen to him for he was a thief and a fugitive.

Lengar loosed the string and the black-feathered arrow struck deep into the stranger’s heart. He must have died in an instant, yet he still thrust his body up as though to fend off the flint arrow-head and then he fell back, shuddered for a few heartbeats, and was still.

Lengar spat on his right hand and rubbed the spittle against the inside of his left wrist where the stranger’s bowstring had lashed and stung the skin; Saban, watching his half-brother, understood then why the stranger wore the strip of stone against his forearm. Lengar danced a few steps, celebrating his kill, but he was nervous. Indeed, he was not certain that the man really was dead for he approached the body very cautiously and prodded it with one horn-tipped end of his bow before leaping back in case the corpse came to life and sprang at him, but the stranger did not move.

Lengar edged forward again, snatched the bag from the stranger’s dead hand and scuttled away from the body. For a moment or two he stared into the corpse’s ashen face, then, confident the man’s spirit was truly gone, he tore the lace that secured the bag’s neck. He peered inside, was motionless for a heartbeat, then screamed for joy. He had been given power.

Saban, terrified by his brother’s scream, shrank back, then edged forward again as Lengar emptied the bag’s contents onto the grass beside the whitened ox-skull. To Saban it looked as though a stream of sunlight tumbled from the leather bag.

There were dozens of small lozenge-shaped gold ornaments, each about the size of a man’s thumbnail, and four great lozenge plaques that were as big as a man’s hand. The lozenges, both big and small, had tiny holes drilled through their narrower points so they could be strung on a sinew or sewn to a garment, and all were made of very thin gold sheets incised with straight lines, though their pattern meant nothing to Lengar who snatched back one of the small lozenges that Saban had dared pick up from the grass. Lengar gathered the lozenges, great and small, into a pile. ‘You know what this is?’ he asked his younger brother, gesturing at the heap.

‘Gold,’ Saban said.

‘Power,’ Lengar said. He glanced at the dead man. ‘Do you know what you can do with gold?’

‘Wear it?’ Saban suggested.

‘Fool! You buy men with it.’ Lengar rocked back on his heels. The cloud shadows were dark now, and the hazels were tossing in the freshening wind. ‘You buy spearmen,’ he said, ‘you buy archers and warriors! You buy power!’

Saban grabbed one of the small lozenges, then dodged out of the way when Lengar tried to take it back. The boy retreated across the small cleared space and, when it appeared that Lengar would not chase him, he squatted and peered at the scrap of gold. It seemed an odd thing with which to buy power. Saban could imagine men working for food or for pots, for flints or for slaves, or for bronze that could be hammered into knives, axes, swords and spearheads, but for this bright metal? It could not cut, it just was, yet even on that clouded day Saban could see how the metal shone. It shone as though a piece of the sun was trapped within the metal and he suddenly shivered, not because he was naked, but because he had never touched gold before; he had never held a scrap of the almighty sun in his hand. ‘We must take it to father,’ he said reverently.

‘So the old fool can add it to his hoard?’ Lengar asked scornfully. He went back to the body and folded the cloak back over the stumps of the arrows to reveal that the dead man’s trews were held up by a belt buckled with a great lump of heavy gold while more of the small lozenges hung on a sinew about his neck.

Lengar glanced at his younger brother, licked his lips, then picked up one of the arrows that had fallen from the stranger’s hand. He was still carrying his longbow and now he placed the black-and-white fledged arrow onto the string. He was gazing into the hazel undergrowth, deliberately avoiding his half-brother’s gaze, but Saban suddenly understood what was in Lengar’s mind. If Saban lived to tell their father of this Outfolk treasure then Lengar would lose it, or would at least have to fight for it, but if Saban were discovered dead, with an Outfolk’s black-and-white feathered arrow in his ribs, then no one would ever suspect that Lengar had done the killing, nor that Lengar had taken a great treasure for his own use. Thunder swelled in the west and the cold wind flattened the tops of the hazel trees. Lengar was drawing back the bow, though still he did not look at Saban. ‘Look at this!’ Saban suddenly cried, holding up the small lozenge. ‘Look!’

Lengar relaxed the bowstring’s pressure as he peered, and at that instant the boy took off like a hare sprung from grass. He burst through the hazels and sprinted across the wide causeway of the Old Temple’s entrance of the sun. There were more rotted posts there, just like the ones around the death house. He had to swerve to negotiate their stumps and, just as he twisted through them, Lengar’s arrow whirred past his ear.

Thunder tore the sky to shreds as the first rain fell. The drops were huge. A stab of lightning flashed down to the opposite hillside. Saban ran, twisting and turning, not daring to look back and see if Lengar pursued him. The rain fell harder and harder, filling the air with its malevolent roar, but making a screen to hide the boy as he ran north and east towards the settlement. He screamed as he ran, hoping that some herdsman might still be on the pastureland, but he saw no one until he had passed the grave mounds at the brow of the hill and was running down the muddy path between the small fields of wheat that were being battered by the drenching rain.

Galeth, Saban’s uncle, and five other men had been returning to the settlement when they heard the boy’s shouts. They turned back up the hill, and Saban ran through the rain to clutch at his uncle’s deerskin jerkin. ‘What is it, boy?’ Galeth asked.

Saban clung to his uncle. ‘He tried to kill me!’ he gasped. ‘He tried to kill me!’

‘Who?’ Galeth asked. He was the youngest brother of Saban’s father, tall, thick-bearded and famous for his feats of strength. Galeth, it was said, had once raised a whole temple pole, and not one of the small ones either, but a big trimmed trunk that jutted high above the other poles. Like his companions, Galeth was carrying a heavy bronze-bladed axe for he had been felling trees when the storm came. ‘Who tried to kill you?’ Galeth asked.