Полная версия:

Sharpe’s Trafalgar: The Battle of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805

SHARPE’S

TRAFALGAR

Richard Sharpe and the Battle

of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805

BERNARD CORNWELL

Copyright

This novel is a work of fiction. The incidents and some of the characters portrayed in it, while based on real historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2000

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 2000

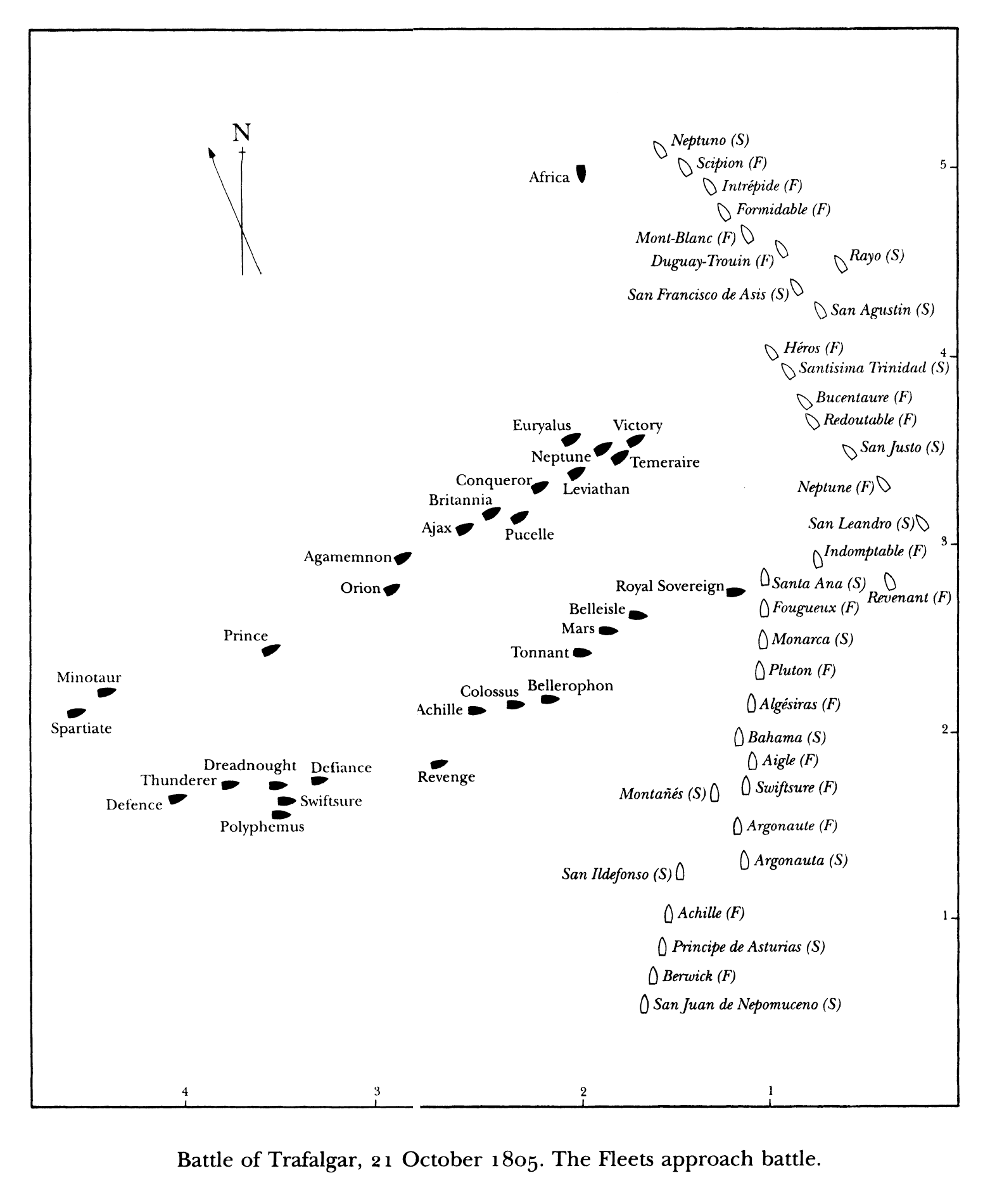

Map © Ken Lewis

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed or included in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007235162

Ebook Edition © JULY 2009 ISBN: 9780007338740

Version: 2017-05-06

Sharpe’s Trafalgar is for Wanda Pan, Anne Knowles, Janet Eastham, Elinor and Rosemary Davenhill, and Maureen Shettle

‘Amid the thunder of cannon and the crack of the lash, Sharpe faces all kinds of perils – but always survives another day. Another rollicking instalment for Cornwell’s Sharpe fans’

The Times

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Map

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Keep Reading

Historical Note

Sharpe’s Story

About the Author

The SHARPE Series (in chronological order)

The SHARPE Series (in order of publication)

Also by Bernard Cornwell

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

‘A hundred and fifteen rupees,’ Ensign Richard Sharpe said, counting the money onto the table.

Nana Rao hissed in disapproval, rattled some beads along the wire bars of his abacus and shook his head. ‘A hundred and thirty-eight rupees, sahib.’

‘One hundred and bloody fifteen!’ Sharpe insisted. ‘It were fourteen pounds, seven shillings and threepence ha’penny.’

Nana Rao examined his customer, gauging whether to continue the argument. He saw a young officer, a mere ensign of no importance, but this lowly Englishman had a very hard face, a scar on his right cheek and showed no apprehension of the two hulking bodyguards who protected Nana Rao and his warehouse. ‘A hundred and fifteen, as you say,’ the merchant conceded, scooping the coins into a large black cash box. He offered Sharpe an apologetic shrug. ‘I get older, sahib, and find I cannot count!’

‘You can count, all right,’ Sharpe said, ‘but you reckon I can’t.’

‘But you will be very happy with your purchases,’ Nana Rao said, for Sharpe had just become the possessor of a hanging bed, two blankets, a teak travelling chest, a lantern and a box of candles, a hogshead of arrack, a wooden bucket, a box of soap, another of tobacco, and a brass and elmwood filtering machine which he had been assured would render water from the filthiest barrels stored in the bottom-most part of a ship’s hold into the sweetest and most palatable liquid.

Nana Rao had demonstrated the filtering machine which he claimed had been brought out from London as part of the baggage of a director of the East India Company who had insisted on only the finest equipment. ‘You put the water here, see?’ The merchant had poured a pint or so of turbid water into the brass upper chamber. ‘And then you allow the water to settle, Mister Sharpe. In five minutes it will be as clear as glass. You observe?’ He lifted the upper container to show water dripping from the packed muslin layers of the filter. ‘I have myself cleaned the filter, Mister Sharpe, and I will warrant the item’s efficiency. It would be a miserable pity to die of mud blockage in the bowel because you would not buy this thing.’

So Sharpe had bought it. He had refused to purchase a chair, bookcase, sofa or washstand, all pieces of furniture that had been used by passengers outward bound from London to Bombay, but he had paid for the filtering machine and all the other goods because otherwise his voyage home would be excruciatingly uncomfortable. Passengers on the great merchantmen of the East India Company were expected to supply their own furniture. ‘Unless you would be liking to sleep on the deck, sahib? Very hard! Very hard!’ Nana Rao had laughed. He was a plump and seemingly friendly man with a large black moustache and a quick smile. His business was to purchase the furniture of incoming passengers which he then sold to those folk who were going home. ‘You will leave the goods here,’ he told Sharpe, ‘and on the day of your embarkation my cousin will deliver them to your ship. Which ship is that?’

‘The Calliope,’ Sharpe said.

‘Ah! The Calliope! Captain Cromwell. Alas, the Calliope is anchored in the roads, so the goods will need to be carried out by boat, but my cousin charges very little for such a service, Mister Sharpe, very little, and when you are happily arrived in London you can sell the items for much profit!’

Which might or, more probably, might not have been true, but was irrelevant because that same night, just two days before Sharpe was to embark, Nana Rao’s godown was burned to the ground and all the goods: the beds, bookcases, lanterns, water filters, blankets, boxes, tables and chairs, the arrack, soap, tobacco, brandy and wine were supposedly consumed with the warehouse. In the morning there was nothing but ashes, smoke and a group of shrieking mourners who wailed that the kindly Nana Rao had died in the conflagration. Happily another godown, not three hundred yards from Nana Rao’s ruined business, was well supplied with all the necessities for the voyage, and that second warehouse did a fine trade as disgruntled passengers replaced their vanished goods at prices that were almost double those that Nana Rao had charged.

Richard Sharpe did not buy anything from the second warehouse. He had been in Bombay for five months, much of that time spent sweating and shivering in the castle hospital, but when the fever had passed, and while he was waiting for the annual convoy to arrive from Britain with the ship that would carry him home, he had explored the city, from the wealthy houses in the Malabar hills to the pestilential alleys by the waterfront. He had found companionship in the alleyways and it was one of those acquaintances who, in return for a golden guinea, gave Sharpe a scrap of information which the ensign reckoned was worth far more than a guinea. It was, indeed, worth a hundred and fifteen rupees which was why, at nightfall, Sharpe was in another alley on the eastern outskirts of the city. He wore his uniform, though over it he had donned a swathing cloak made of cheap sacking which was thickly impregnated with mud and filth. He limped and shuffled, his body bent over with a hand outstretched as though he were begging. He muttered to himself and twitched, and sometimes turned and snarled at some innocent soul for no apparent reason. He went utterly unnoticed.

He found the house he wanted and squatted by its wall. A score of beggars, some horribly maimed, were gathered by the gate along with almost a hundred petitioners who waited for the house’s owner, a wealthy merchant, to return from his place of business. The merchant came after nightfall, riding in a curtained palanquin that was carried by eight men, while another dozen men whacked the beggars out of the way with long staves, but, once the merchant’s palanquin was safe inside the courtyard, the gates were left open so that the petitioners and beggars could follow. The beggars, Sharpe among them, were pushed to one side of the yard while the petitioners gathered at the foot of the broad steps that climbed to the house door. Lanterns hung from the coconut palms that arched over the yard, while from inside the big house yellow candlelight glimmered behind filigree shutters. Sharpe pushed as close to the house as he could, staying in the shadow of the palm trunks. Under the greasy cloak he had his cavalry sabre and a loaded pistol, though he hoped he would need neither weapon.

The merchant was called Panjit and he kept the petitioners and beggars waiting until he had eaten his evening meal, but then the house door was thrown open and Panjit, resplendent in a long robe of embroidered yellow silk, appeared on the top step. The petitioners called aloud while the beggars shuffled forward until they were driven back by the staves of the bodyguards. The merchant smiled then rang a small handbell to attract the attention of a brightly painted god who sat in a niche of the courtyard wall. Panjit bowed to the god, and then, in answer to Sharpe’s prayers, a second man, this one dressed in a red silk robe, emerged from the house door.

That second man was Nana Rao. He had a wide smile, and no wonder, for he was quite untouched by fire and, as Sharpe’s guinea had discovered, he was also first cousin of Panjit who was the merchant who had profited so greatly by owning the second warehouse that had replaced the goods supposedly destroyed in Nana Rao’s calamitous fire. It had been a slick deception, enabling the cousins to sell the same goods twice, and tonight, replete with their swollen profits, they were choosing which men would be given the lucrative job of rowing the passengers and their belongings out to the great ships that lay in the anchorage. The chosen men would be required to pay for the privilege, thus enriching Panjit and Nana Rao even more, and the two cousins, aware of their good fortune, planned to propitiate the gods by distributing some petty coins to the beggars. Sharpe was reckoning that he could reach Nana Rao in the guise of a supplicant, then throw off the filthy cloak and shame the man into returning his money. The competent-looking bodyguards at the foot of the steps suggested that his skimpy plan might prove more complicated than he envisaged, but Sharpe guessed Nana Rao would not want his deception revealed and so would probably be happy to pay him off.

Sharpe was close to the house now. He had noticed that the empty palanquin had been carried down a narrow and dark passage that led alongside the building, evidently giving access to a courtyard at the rear of the house, and he was considering going down the passage and coming back through the building to approach Nana Rao from the rear, but any of the beggars who ventured near the passage were beaten back by the bodyguards. The petitioners were being allowed onto the steps in small groups, but the beggars were expected to wait until the main business of the evening was over.

Sharpe suspected it would be a long night, but he was content to wait with his cloak hood pulled over his face. He squatted against the wall, watching for an opportunity to dash into the passageway beside the house, but then a servant who had been guarding the outer gate pushed through the crowd and spoke in Panjit’s ear. For an instant the merchant looked alarmed and a silence fell over the courtyard, but then he whispered to Nana Rao who just shrugged. Panjit clapped his hands and shouted at the bodyguards who energetically drove the petitioners back to form an open passage between the gate and the steps. Someone was plainly coming to the house and Nana Rao, nervous of their appearance, stepped into the black shadow at the back of the porch.

The way was clear now for Sharpe to go down the passage beside the house, but curiosity held him in place. There was a commotion in the alley, sounding like the jeers and scramble that always accompanied a band of constables marching through the lesser streets of London, then the outer gate was pushed fully open and Sharpe could only stare in astonishment.

A group of British sailors stood in the gate, led by a naval captain, a post captain no less, who was immaculate in cocked hat, blue frock coat, silk breeches and stockings, silver-buckled shoes and slim sword. The lantern light reflected from the heavy gold bullion of his twin epaulettes. He took off his hat, revealing thick blond hair, smiled and bowed. ‘Do I have the honour,’ he asked, ‘of coming to the house of Panjit Lashti?’

Panjit nodded cautiously. ‘This is the house,’ he said in English.

The naval captain put on his cocked hat. ‘I have come,’ he announced in a friendly voice that had a distinct Devonshire accent, ‘for Nana Rao.’

‘He is not here,’ Panjit answered.

The captain glanced at the red-robed figure in the porch shadows. ‘His ghost will do very well.’

‘I have answered you,’ Panjit said, defiance now making his voice angry. ‘He is not here. He is dead.’

The captain smiled. ‘My name is Chase,’ he said courteously, ‘Captain Joel Chase of His Britannic Majesty’s navy, and I would be obliged if Nana Rao would come with me.’

‘His body was burned,’ Panjit declared fiercely, ‘and his ashes have gone to the river. Why do you not seek him there?’

‘He’s no more dead than you or I,’ Chase said, then waved his men forward. He had brought a dozen seamen, all identically dressed in white duck trousers, red and white hooped shirts and straw hats stiffened with pitch and circled with red and white ribbons. They wore long pigtails and carried thick staves which Sharpe guessed were capstan bars. Their leader was a huge man whose bare forearms were thick with tattoos, while beside him was a Negro, every bit as tall, who carried his capstan bar as though it were a hazel wand. ‘Nana Rao’ – Chase abandoned the pretence that the merchant was dead – ‘you owe me a deal of money and I have come to collect it.’

‘What is your authority to be here?’ Panjit demanded. The crowd, most of whom did not understand English, watched the sailors nervously, but Panjit’s bodyguards, who outnumbered Chase’s men and were just as well armed, seemed eager to be loosed on the seamen.

‘My authority,’ Chase said grandly, ‘is my empty purse.’ He smiled. ‘You surely do not wish me to use force?’

‘Use force, Captain Chase,’ Panjit answered just as grandly, ‘and I shall have you in front of a magistrate by dawn.’

‘I shall happily appear in court,’ Chase said, ‘so long as Nana Rao is beside me.’

Panjit shook his hands as if he was shooing Chase and his men away from his courtyard. ‘You will leave, Captain. You will leave my house now.’

‘I think not,’ Chase said.

‘Go! Or I will summon authority!’ Panjit insisted.

Chase turned to the huge tattooed man. ‘Nana Rao’s the bugger with the moustache and the red silk robe, Bosun. Get him.’

The British seamen charged forward, relishing the chance of a scrap, but Panjit’s bodyguards were no less eager and the two groups met in the courtyard’s centre with a sickening crash of staves, skulls and fists. The seamen had the best of it at first, for they had charged with a ferocity that drove the bodyguards back to the foot of the steps, but Panjit’s men were both more numerous and more accustomed to fighting with the long clubs. They rallied at the steps, then used their staves like spears to tangle the sailors’ legs and, one by one, the pigtailed men were tripped and beaten down. The bosun and the Negro were the last to fall. They tried to protect their captain who was using his fists handily, but the British sailors had woefully underestimated the opposition and were doomed.

Sharpe sidled towards the steps, elbowing the beggars aside. The crowd was jeering at the defeated British seamen, Panjit and Nana Rao were laughing, while the petitioners, emboldened by the success of the bodyguards, jostled each other for a chance to kick the fallen men. Some of the bodyguards were wearing the sailors’ tarred hats while another pranced in triumph with Chase’s cocked hat on his head. The captain was a prisoner, his arms pinioned by two men.

One of the bodyguards had stayed with Panjit and saw Sharpe edging towards the steps. He came down fast, shouting that Sharpe should go back, and when the cloaked beggar did not obey he aimed a kick at him. Sharpe grabbed the man’s foot and kept it swinging upwards so that the bodyguard fell on his back and his head struck the bottom step with a sickening thump that went unnoticed in the noisy celebration of the British defeat. Panjit was shouting for quiet, holding his hands aloft. Nana Rao was laughing, his shoulders heaving with merriment, while Sharpe was in the shadow of the bushes at the side of the steps.

The victorious bodyguards pushed the petitioners and beggars away from the bruised and bloodied sailors who, disarmed, could only watch as their dishevelled captain was ignominiously hustled to the bottom of the steps. Panjit shook his head in mock sadness. ‘What am I to do with you, Captain?’

Chase shook his hands free. His fair hair was darkened by blood that trickled down his cheek, but he was still defiant. ‘I suggest,’ he said, ‘that you give me Nana Rao and pray to whatever god you trust that I do not bring you before the magistrates.’

Panjit looked pained. ‘It is you, Captain, who will be in court,’ he said, ‘and how will that look? Captain Chase of His Britannic Majesty’s navy, convicted of forcing his way into a private house and there brawling like a drunkard? I think, Captain Chase, that you and I had better discuss what terms we can agree to avoid that fate.’ Panjit waited, but Chase said nothing. He was beaten. Panjit frowned at the bodyguard who had the captain’s hat and ordered the man to give it back, then smiled. ‘I do not want a scandal any more than you, Captain, but I shall survive any scandal that this sad affair starts, and you will not, so I think you had better make me an offer.’

A loud click interrupted Panjit. It was not a single click, but more like a loud metallic scratching that ended in the solid sound of a pistol being cocked, and Panjit turned to see that a red-coated British officer with black hair and a scarred face was standing beside his cousin, holding a blackened pistol muzzle at Nana Rao’s temple.

The bodyguards glanced at Panjit, saw his uncertainty, and some of them hefted their staves and moved towards the steps, but Sharpe gripped Nana Rao’s hair with his left hand and kicked him in the back of the knees so that the merchant dropped hard down with a cry of hurt surprise. The sudden brutality and Sharpe’s evident readiness to pull the trigger checked the bodyguards. ‘I think you’d better make me an offer,’ Sharpe said to Panjit, ‘because this dead cousin of yours owes me fourteen pounds, seven shillings and threepence ha’penny.’

‘Put the pistol away,’ Panjit said, waving his bodyguards back. He was nervous. Dealing with a courteous naval captain who was an obvious gentleman was one thing, but the red-coated ensign looked wild, and the pistol’s muzzle was grinding into Nana Rao’s skull so that the merchant whimpered with pain. ‘Just put the pistol away,’ Panjit said soothingly.

‘You think I’m daft?’ Sharpe sneered. ‘Besides, the magistrates can’t do anything to me if I shoot your cousin. He’s already dead! You said so yourself. He’s nothing but ashes in the river.’ He twisted Nana Rao’s hair, making the kneeling man gasp. ‘Fourteen pounds,’ Sharpe said, ‘seven shillings and threepence ha’penny.’

‘I’ll pay it!’ Nana Rao gasped.

‘And Captain Chase wants his money too,’ Sharpe said.

‘Two hundred and sixteen guineas,’ Chase said, brushing off his hat, ‘though I think we deserve a little more for having worked the miracle of bringing Nana Rao back to life!’

Panjit was no fool. He looked at Chase’s seamen who were picking up their capstan bars and readying themselves to continue the fight. ‘No magistrates?’ he asked Sharpe.

‘I hate magistrates,’ Sharpe said.

Panjit’s face betrayed a flicker of a smile. ‘If you were to let go of my cousin’s hair,’ he suggested, ‘then I think we can all talk business.’

Sharpe let go of Nana Rao, lowered the flint of the pistol and stepped back. He stood momentarily to attention. ‘Ensign Sharpe, sir,’ he introduced himself to Chase.

‘You are no ensign, Sharpe, but a ministering angel.’ Chase climbed the steps with an outstretched hand. Despite the blood on his face he was a good-looking man with a confidence and friendliness that seemed to come from a contented and good-natured character. ‘You are the deus ex machina, Ensign, as welcome as a whore on a gundeck or a breeze in the horse latitudes.’ He spoke lightly, but there was no doubting the fervency of his thanks and, instead of shaking Sharpe’s hand, he embraced him. ‘Thank you,’ he whispered, then stepped back. ‘Hopper!’

‘Sir?’ The huge bosun with the tattooed arms who had been laying enemies left and right before he was overwhelmed stepped forward.

‘Clear the decks, Hopper. Our enemies wish to discuss surrender terms.’

‘Aye aye, sir.’

‘And this is Ensign Sharpe, Hopper, and he is to be treated as a most honoured friend.’

‘Aye aye, sir,’ Hopper said, grinning.

‘Hopper commands my barge crew,’ Chase explained to Sharpe, ‘and those battered gentlemen are his oarsmen. This night may not go down as one of our greater victories, gentlemen’ – Chase was now addressing his bruised and bleeding men – ‘but a victory it still is, and I thank you.’

The yard was cleared, chairs were fetched from the house, and terms discussed.

It had been a guinea, Sharpe thought, exceedingly well spent.

‘I rather liked the fellows,’ Chase said.

‘Panjit and Nana Rao? They’re rogues,’ Sharpe said. ‘I liked them too.’

‘Took their defeat like gentlemen!’

‘They got off light, sir,’ Sharpe said. ‘Must have made a fortune on that fire.’

‘Oldest trick in the bag,’ Captain Chase said. ‘There used to be a fellow on the Isle of Dogs who claimed thieves had cleaned out his chandlery on the night before some foreign ship sailed, and the victims always fell for it.’ Chase chuckled and Sharpe said nothing. He had known the man Chase spoke of, and had even helped him clear the warehouse one night, but he thought it best to be silent. ‘But you and I are all right, Sharpe, other than a scratch and a bruise,’ Chase went on, ‘and that’s all that matters, eh?’

‘We’re all right, sir,’ Sharpe agreed. The two men, followed by Chase’s barge crew, were walking back through the pungent alleys of Bombay and both were carrying money. Chase had originally contracted with Rao to supply his ship with rum, brandy, wine and tobacco, and now, instead of the two hundred and sixteen guineas he had paid the merchant, he was carrying three hundred, while Sharpe had two hundred rupees, so all in all, Sharpe reckoned, it had been a good evening’s work, especially as Panjit had promised to supply Sharpe with the bed, blankets, bucket, lantern, chest, arrack, tobacco, soap and filter machine, all to be delivered to the Calliope at dawn and at no cost to Sharpe. The two Indians had been eager to placate the Englishmen once they realized that Chase and Sharpe had no intention of telling the rest of the fleeced victims that Nana Rao still lived, and so the merchants had fed their unwanted guests, plied them with arrack, paid the money, sworn eternal friendship and bid them good night. Now Chase and Sharpe groped their way through the dark city.