Полная версия:

Sharpe’s Havoc: The Northern Portugal Campaign, Spring 1809

SHARPE’S

HAVOC

Richard Sharpe and the campaign in northern Portugal, Spring 1809

BERNARD CORNWELL

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2003

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 2003

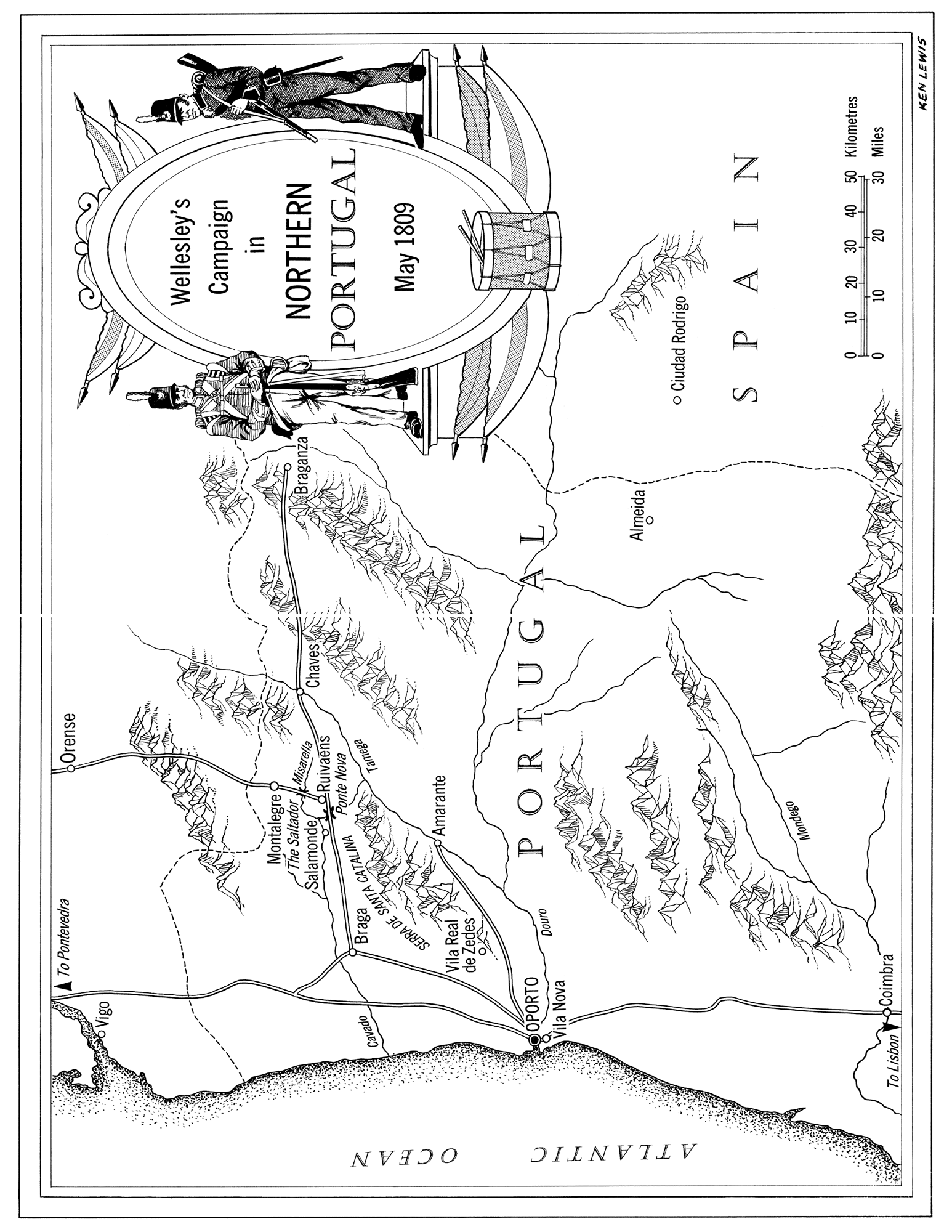

Map © Ken Lewis

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Ebook Edition © July 2009 ISBN: 9780007338689

Version: 2017-05-06

This novel is a work of fiction.

The incidents and some of the characters portrayed in it, while based on real historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Sharpe’s Havoc is for William T. Oughtred who knows why

‘This book has the same combination of thorough research and narrative drive that distinguished its predecessors. A gripping read’

Independent

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Map

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Historical Note

Sharpe’s Story

About the Author

The SHARPE Series (in chronological order)

The SHARPE Series (in order of publication)

Also by Bernard Cornwell

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

Miss Savage was missing.

And the French were coming.

The approach of the French was the more urgent crisis. The splintering noise of sustained musket fire was sounding just outside the city and in the last ten minutes five or six cannonballs had battered through the roofs of the houses high on the river’s northern bank. The Savage house was a few yards down the slope and for the moment was protected from errant French cannon fire, but already the warm spring air hummed with spent musket balls that sometimes struck the thick roof tiles with a loud crack or else ripped through the dark glossy pines to shower needles over the garden. It was a large house, built of white-painted stone and with dark-green shutters closed over the windows. The front porch was crowned with a wooden board on which were gilded letters spelling out the name House Beautiful in English. It seemed an odd name for a building high on the steep hillside where the city of Oporto overlooked the River Douro in northern Portugal, especially as the big square house was not beautiful at all, but quite stark and ugly and angular, even if its harsh lines were softened by dark cedars which would offer welcome shade in summer. A bird was making a nest in one of the cedars and whenever a musket ball tore through the branches it would squawk in alarm and fly a small loop before returning to its work. Scores of fugitives were fleeing past the House Beautiful, running down the hill towards the ferries and the pontoon bridge that would take them safe across the Douro. Some of the refugees drove pigs, goats and cattle, others pushed handcarts precariously loaded with furniture, and more than one carried a grandparent on his back.

Richard Sharpe, Lieutenant in the second battalion of His Majesty’s 95th Rifles, unbuttoned his breeches and pissed on the narcissi in the House Beautiful’s front flower bed. The ground was soaked because there had been a storm the previous night. Lightning had flickered above the city, thunder had billowed across the sky and the heavens had opened so that the flower beds now steamed gently as the hot sun drew out the night’s moisture. An howitzer shell arched overhead, sounding like a ponderous barrel rolling swiftly over attic floorboards. It left a small grey trace of smoke from its burning fuse. Sharpe looked up at the smoke tendril, judging from its curve where the howitzer had to be emplaced. ‘They’re getting too bloody close,’ he said to no one in particular.

‘You’ll be drowning those poor bloody flowers, so you will,’ Sergeant Harper said, then added a hasty ‘sir’ when he saw Sharpe’s face.

The howitzer shell exploded somewhere above the tangle of alleys close to the river and a heartbeat later the French cannonade rose to a sustained thunder, but the thunder had a crisp, clear, staccato timbre, suggesting that some of the guns were very close. A new battery, Sharpe thought. It must have unlimbered just outside the city, maybe half a mile away from Sharpe, and was probably whacking the big northern redoubt in the flank, and the musketry that had been sounding like the burning of a dry thorn bush now faded to an intermittent crackle, suggesting that the defending infantry was retreating. Some, indeed, were running and Sharpe could hardly blame them. A large and disorganized Portuguese force, led by the Bishop of Oporto, was trying to stop Marshal Soult’s army from capturing the city, the second largest in Portugal, and the French were winning. The Portuguese road to safety led past the front garden of the House Beautiful and the bishop’s blue-coated soldiers were bolting down the hill as fast as their legs could take them, except that when they saw the green-jacketed British riflemen they slowed to a walk as if to prove that they were not panicking. And that, Sharpe reckoned, was a good sign. The Portuguese evidently had pride, and troops with pride would fight well given another chance, though not all the Portuguese troops showed such spirit. The men from the ordenança kept running, but that was hardly surprising. The ordenança was an enthusiastic but unskilled army of volunteers raised to defend the homeland and the battle-hardened French troops were tearing them to shreds.

Meanwhile Miss Savage was still missing.

Captain Hogan appeared on the front porch of the House Beautiful. He carefully closed the door behind him and then looked up to heaven and swore fluently and impressively. Sharpe buttoned his breeches and his two dozen riflemen inspected their weapons as though they had never seen such things before. Captain Hogan added a few more carefully chosen words, then spat as a French round shot trundled overhead. ‘What it is, Richard,’ he said when the cannon shot had passed, ‘is a shambles. A bloody, goddamned miserable poxed bollocks of an agglomerated halfwitted shambles.’ The round shot landed somewhere in the lower town and precipitated the splintering crash of a collapsing roof. Captain Hogan took out his snuff box and inhaled a mighty pinch.

‘Bless you,’ Sergeant Harper said.

Captain Hogan sneezed and Harper smiled.

‘Her name,’ Hogan said, ignoring Harper, ‘is Katherine or, rather, Kate. Kate Savage, nineteen years old and in need, my God, how she is in need, of a thrashing! A hiding! A damned good smacking, that’s what she needs, Richard. A copper-sheathed, goddamned bloody good walloping.’

‘So where the hell is she?’ Sharpe asked.

‘Her mother thinks she might have gone to Vila Real de Zedes,’ Captain Hogan said, ‘wherever in God’s holy hell that might be. But the family has an estate there. A place where they go to escape the summer heat.’ He rolled his eyes in exasperation.

‘So why would she go there, sir?’ Sergeant Harper asked.

‘Because she’s a fatherless nineteen-year-old girl,’ Hogan said, ‘who insists on having her own way. Because she’s fallen out with her mother. Because she’s a bloody idiot who deserves a ruddy good hiding. Because, oh I don’t know why! Because she’s young and knows everything, that’s why.’ Hogan was a stocky, middle-aged Irishman, a Royal Engineer, with a shrewd face, a soft brogue, greying hair and a charitable disposition. ‘Because she’s a bloody halfwit, that’s why,’ he finished.

‘This Vila Real de whatever,’ Sharpe said, ‘is it far? Why don’t we just fetch her?’

‘Which is precisely what I’ve told the mother you will do, Richard. You will go to Vila Real de Zedes, you will find the wretched girl and you will get her across the river. We’ll wait for you in Vila Nova and if the damned French capture Vila Nova then we’ll wait for you in Coimbra.’ He paused as he pencilled these instructions on a scrap of paper. ‘And if the Frogs take Coimbra we’ll wait for you in Lisbon, and if the bastards take Lisbon we’ll be pissing our breeches in London and you’ll be God knows where. Don’t fall in love with her,’ he went on, handing Sharpe the piece of paper, ‘don’t get the silly girl pregnant, don’t give her the thrashing she bloody well deserves and don’t, for the love of Christ, lose her, and don’t lose Colonel Christopher either. Am I plain?’

‘Colonel Christopher is coming with us?’ Sharpe asked, appalled.

‘Didn’t I just tell you that?’ Hogan enquired innocently, then turned as a clatter of hooves announced the appearance of the widow Savage’s travelling coach from the stable yard at the rear of the house. The coach was heaped with baggage and there was even some furniture and two rolled carpets lashed onto the rear rack where a coachman, precariously poised between a half-dozen gilded chairs, was leading Hogan’s black mare by the reins. The Captain took the horse and used the coach’s mounting step to hoist himself into the saddle. ‘You’ll be back with us in a couple of days,’ he assured Sharpe. ‘Say six, seven hours to Vila Real de Zedes? The same back to the ferry at Barca d’Avintas and then a quiet stroll home. You know where Barca d’Avintas is?’

‘No, sir.’

‘That way.’ Hogan pointed eastwards. ‘Four country miles.’ He pushed his right boot into its stirrup, then lifted his body to flick out the tails of his blue coat. ‘With luck you may even rejoin us tomorrow night.’

‘What I don’t understand …’ Sharpe began, then paused because the front door of the house had been thrown open and Mrs Savage, widow and mother of the missing daughter, came into the sunlight. She was a good-looking woman in her forties: dark-haired, tall and slender with a pale face and high arched eyebrows. She hurried down the steps as a cannonball rumbled overhead and then there was a smattering of musket fire alarmingly close, so close that Sharpe climbed the porch steps to stare at the crest of the hill where the Braga road disappeared between a large tavern and a handsome church. A Portuguese six-pounder gun had just been deployed by the church and was now firing at the invisible enemy. The bishop’s forces had dug new redoubts on the crest and patched the old medieval wall with hastily erected palisades and earthworks, but the sight of the small gun firing from its makeshift position in the centre of the road suggested that those defences were crumbling fast.

Mrs Savage sobbed that her baby daughter was lost, then Captain Hogan managed to persuade the widow into the carriage. Two servants laden with bags stuffed with clothes followed their mistress into the vehicle. ‘You will find Kate?’ Mrs Savage pushed open the door and enquired of Captain Hogan.

‘The precious darling will be with you very soon,’ Hogan said reassuringly. ‘Mister Sharpe will see to that,’ he added, then used his foot to close the coach door on Mrs Savage, who was the widow of one of the many British wine merchants who lived and worked in the city of Oporto. She was rich, Sharpe presumed, certainly rich enough to own a fine carriage and the lavish House Beautiful, but she was also foolish for she should have left the city two or three days before, but she had stayed because she had evidently believed the bishop’s assurance that he could repel Marshal Soult’s army. Colonel Christopher, who had once lodged in the strangely named House Beautiful, had appealed to the British forces south of the river to send men to escort Mrs Savage safely away and Captain Hogan had been the closest officer and Sharpe, with his riflemen, had been protecting Hogan while the engineer mapped northern Portugal, and so Sharpe had come north across the Douro with twenty-four of his men to escort Mrs Savage and any other threatened British inhabitants of Oporto to safety. Which should have been a simple enough task, except that at dawn the widow Savage had discovered that her daughter had fled from the house.

‘What I don’t understand,’ Sharpe persevered, ‘is why she ran away.’

‘She’s probably in love,’ Hogan explained airily. ‘Nineteen-year-old girls of respectable families are dangerously susceptible to love because of all the novels they read. See you in two days, Richard, or maybe even tomorrow? Just wait for Colonel Christopher, he’ll be with you directly, and listen.’ He bent down from the saddle and lowered his voice so that no one but Sharpe could hear him. ‘Keep a close eye on the Colonel, Richard. I worry about him, I do.’

‘You should worry about me, sir.’

‘I do that too, Richard, I do indeed,’ Hogan said, then straightened up, waved farewell and spurred his horse after Mrs Savage’s carriage which had swung out of the front gate and joined the stream of fugitives going towards the Douro.

The sound of the carriage wheels faded. The sun came from behind a cloud just as a French cannonball struck a tree on the hill’s crest and exploded a cloud of reddish blossom which drifted above the city’s steep slope. Daniel Hagman stared at the airborne blossom. ‘Looks like a wedding,’ he said and then, glancing up as a musket ball ricocheted off a roof tile, brought a pair of scissors from his pocket. ‘Finish your hair, sir?’

‘Why not, Dan,’ Sharpe said. He sat on the porch steps and took off his shako.

Sergeant Harper checked that the sentinels were watching the north. A troop of Portuguese cavalry had appeared on the crest where the single cannon was firing bravely. A rattle of musketry proved that some infantry was still fighting, but more and more troops were retreating past the house and Sharpe knew it could only be a matter of minutes before the city’s defences collapsed entirely. Hagman began slicing away at Sharpe’s hair. ‘You don’t like it over the ears, ain’t that right?’

‘I like it short, Dan.’

‘Short like a good sermon, sir,’ Hagman said. ‘Now keep still, sir, just keep still.’ There was a sudden stab of pain as Hagman speared a louse with the scissors’ blade. He spat on the drop of blood that showed on Sharpe’s scalp, then wiped it away. ‘So the Crapauds will get the city, sir?’

‘Looks like it,’ Sharpe said.

‘And they’ll march on Lisbon next?’ Hagman asked, cutting away.

‘Long way to Lisbon,’ Sharpe said.

‘Maybe, sir, but there’s an awful lot of them, sir, and precious few of us.’

‘But they say Wellesley’s coming here,’ Sharpe said.

‘As you keep telling us, sir,’ Hagman said, ‘but is he really a miracle worker?’

‘You fought at Copenhagen, Dan,’ Sharpe said, ‘and down the coast here.’ He meant the battles at Rolica and Vimeiro. ‘You could see for yourself.’

‘From the skirmish line, sir, all generals are the same,’ Hagman said, ‘and who knows if Sir Arthur’s really coming?’ It was, after all, only a rumour that Sir Arthur Wellesley was taking over from General Cradock and not everyone believed it. Many thought the British would withdraw, ought to withdraw, that they should give up the game and let the French have Portugal. ‘Turn your head to the right,’ Hagman said. The scissors clicked busily, not even pausing as a round shot buried itself in the church at the hill’s top. A mist of dust showed beside the whitewashed bell tower down which a crack had suddenly appeared. The Portuguese cavalry had been swallowed by the gun smoke and a trumpet called far away. There was a burst of musketry, then silence. A building must have been burning beyond the crest for there was a great smear of smoke drifting westwards. ‘Why would someone call their home the House Beautiful?’ Hagman wondered.

‘Didn’t know you could read, Dan,’ Sharpe said.

‘I can’t, sir, but Isaiah read it to me.’

‘Tongue!’ Sharpe called. ‘Why would someone call their home House Beautiful?’

Isaiah Tongue, long and thin and dark and educated, who had joined the army because he was a drunk and thereby lost his respectable job, grinned. ‘Because he’s a good Protestant, sir.’

‘Because he’s a bloody what?’

‘It’s from a book by John Bunyan,’ Tongue explained, ‘called Pilgrim’s Progress.’

‘I’ve heard of that,’ Sharpe said.

‘Some folk consider it essential reading,’ Tongue said airily, ‘the story of a soul’s journey from sin to salvation, sir.’

‘Just the thing to keep you burning the candles at night,’ Sharpe said.

‘And the hero, Christian, calls at the House Beautiful, sir,’ – Tongue ignored Sharpe’s sarcasm – ‘where he talks with four virgins.’

Hagman laughed. ‘Let’s get inside now, sir.’

‘You’re too old for a virgin, Dan,’ Sharpe said.

‘Discretion,’ Tongue said, ‘Piety, Prudence and Charity.’

‘What about them?’ Sharpe asked.

‘Those were the names of the virgins, sir,’ Tongue said.

‘Bloody hell,’ Sharpe said.

‘Charity’s mine,’ Hagman said. ‘Pull your collar down, sir, that’s the way.’ He snipped at the black hair. ‘He sounds like he was a tedious old man, Mister Savage, if it was him what named the house.’ Hagman stooped to manoeuvre the scissors over Sharpe’s high collar. ‘So why did the Captain leave us here, sir?’ he asked.

‘He wants us to look after Colonel Christopher,’ Sharpe said.

‘To look after Colonel Christopher,’ Hagman repeated, making his disapproval evident by the slowness with which he said the words. Hagman was the oldest man in Sharpe’s troop of riflemen, a poacher from Cheshire who was a deadly shot with his Baker rifle. ‘So Colonel Christopher can’t look after himself now?’

‘Captain Hogan left us here, Dan,’ Sharpe said, ‘so he must think the Colonel needs us.’

‘And the Captain’s a good man, sir,’ Hagman said. ‘You can let the collar go. Almost done.’

But why had Captain Hogan left Sharpe and his riflemen behind? Sharpe wondered about that as Hagman tidied up his work. And had there been any significance in Hogan’s final injunction to keep a close eye on the Colonel? Sharpe had only met the Colonel once. Hogan had been mapping the upper reaches of the River Cavado and the Colonel and his servant had ridden out of the hills and shared a bivouac with the riflemen. Sharpe had not liked Christopher who had been supercilious and even scornful of Hogan’s work. ‘You map the country, Hogan,’ the Colonel had said, ‘but I map their minds. A very complicated thing, the human mind, not simple like hills and rivers and bridges.’ Beyond that statement he had not explained his presence, but just ridden on next morning. He had revealed that he was based in Oporto which, presumably, was how he had met Mrs Savage and her daughter, and Sharpe wondered why Colonel Christopher had not persuaded the widow to leave Oporto much sooner.

‘You’re done, sir,’ Hagman said, wrapping his scissors in a piece of calfskin, ‘and you’ll be feeling the cold wind now, sir, like a newly shorn sheep.’

‘You should get your own hair cut, Dan,’ Sharpe said.

‘Weakens a man, sir, weakens him something dreadful.’ Hagman frowned up the hill as two round shots bounced on the crest of the road, one of them taking off the leg of a Portuguese gunner. Sharpe’s men watched expressionless as the round shot bounded on, spraying blood like a Catherine wheel, to finally bang and stop against a garden wall across the road. Hagman chuckled. ‘Fancy calling a girl Discretion! It ain’t a natural name, sir. Ain’t kind to call a girl Discretion.’

‘It’s in a book, Dan,’ Sharpe said, ‘so it isn’t supposed to be natural.’ He climbed to the porch and shoved hard on the front door, but found it locked. So where the hell was Colonel Christopher? More Portuguese retreated down the slope and these men were so frightened that they did not pause when they saw the British troops, but just kept running. The Portuguese cannon was being attached to its limber and spent musket balls were tearing at the cedars and rattling against the tiles, shutters and stones of the House Beautiful. Sharpe hammered on the locked door, but there was no answer.

‘Sir?’ Sergeant Patrick Harper called a warning to him. ‘Sir?’ Harper jerked his head towards the side of the house and Sharpe backed away from the door to see Lieutenant Colonel Christopher riding from the stable yard. The Colonel, who was armed with a sabre and a brace of pistols, was cleaning his teeth with a wooden pick, something he did frequently, evidently because he was proud of his even white smile. He was accompanied by his Portuguese servant who, mounted on his master’s spare horse, was carrying an enormous valise that was so stuffed with lace, silk and satins that the bag could not be closed.

Colonel Christopher curbed his horse, took the toothpick from his mouth, and stared in astonishment at Sharpe. ‘What on earth are you doing here, Lieutenant?’

‘Ordered to stay with you, sir,’ Sharpe answered. He glanced again at the valise. Had Christopher been looting the House Beautiful?

The Colonel saw where Sharpe was looking and snarled at his servant, ‘Close it, damn you, close it.’ Christopher, even though his servant spoke good English, used his own fluent Portuguese, then looked back to Sharpe. ‘Captain Hogan ordered you to stay with me. Is that what you’re trying to convey?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘And how the devil are you supposed to do that, eh? I have a horse, Sharpe, and you do not. You and your men intend to run, perhaps?’

‘Captain Hogan gave me an order, sir,’ Sharpe answered woodenly. He had learned as a sergeant how to deal with difficult senior officers. Say little, say it tonelessly, then say it all again if necessary.

‘An order to do what?’ Christopher enquired patiently.

‘Stay with you, sir. Help you find Miss Savage.’

Colonel Christopher sighed. He was a black-haired man in his forties, but still youthfully handsome with just a distinguished touch of grey at his temples. He wore black boots, plain black riding breeches, a black cocked hat and a red coat with black facings. Those black facings had prompted Sharpe, on his previous meeting with the Colonel, to ask whether Christopher served in the Dirty Half Hundred, the 50th regiment, but the Colonel had treated the question as an impertinence. ‘All you need to know, Lieutenant, is that I serve on General Cradock’s staff. You have heard of the General?’ Cradock was the General in command of the British forces in southern Portugal and if Soult kept marching then Cradock must face him. Sharpe had stayed silent after Christopher’s response, but Hogan had later suggested that the Colonel was probably a ‘political’ soldier, meaning he was no soldier at all, but rather a man who found life more convenient if he was in uniform. ‘I’ve no doubt he was a soldier once,’ Hogan had said, ‘but now? I think Cradock got him from Whitehall.’