Полная версия:

Sharpe’s Fortress: The Siege of Gawilghur, December 1803

SHARPE’S

FORTRESS

Richard Sharpe and the Siege

of Gawilghur, December 1803

BERNARD CORNWELL

Copyright

This novel is a work of fiction. The incidents and some of the characters portrayed in it, while based on real historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1999

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 1999

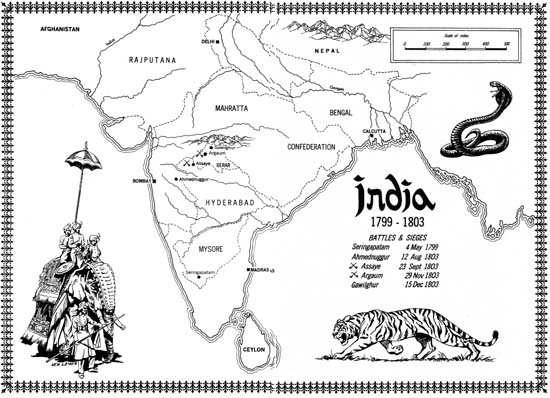

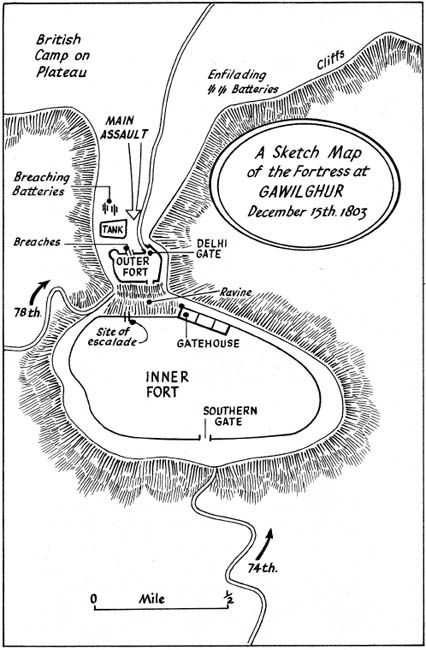

Map © Ken Lewis

Cover design by Holly Macdonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018. Cover photographs © Alamy Stock Photo

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006510314

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2010 ISBN: 9780007346806

Version: 2018-04-13

Sharpe’s Fortress is for Christine Clarke, with many thanks

‘We cheer Sharpe on. He has a kind of angry courage, an inability to stay away from a fight, and a permanent inner battle between his inclinations and his sense of duty. Wellington wound up a dangerous spring on the day he raised Sharpe from the ranks. It’s our magnificent gain’

Terry Pratchett

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Praise

Maps

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Keep Reading

Historical Note

Sharpe’s Story

About the Author

The SHARPE Series (in chronological order)

The SHARPE Series (in order of publication)

Also by Bernard Cornwell

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

Richard Sharpe wanted to be a good officer. He truly did. He wanted it above all other things, but somehow it was just too difficult, like trying to light a tinderbox in a rain-filled wind. Either the men disliked him, or they ignored him, or they were over-familiar and he was unsure how to cope with any of the three attitudes, while the battalion’s other officers plain disapproved of him. You can put a racing saddle on a carthorse, Captain Urquhart had said one night in the ragged tent which passed for the officers’ mess, but that don’t make the beast quick. He had not been talking about Sharpe, not directly, but all the other officers glanced at him.

The battalion had stopped in the middle of nowhere. It was hot as hell and no wind alleviated the sodden heat. They were surrounded by tall crops that hid everything except the sky. A cannon fired somewhere to the north, but Sharpe had no way of knowing whether it was a British gun or an enemy cannon.

A dry ditch ran through the tall crops and the men of the company sat on the ditch lip as they waited for orders. One or two lay back and slept with their mouths wide open while Sergeant Colquhoun leafed though his tattered Bible. The Sergeant was short-sighted, so had to hold the book very close to his nose from which drops of sweat fell onto the pages. Usually the Sergeant read quietly, mouthing the words and sometimes frowning when he came across a difficult name, but today he was just slowly turning the pages with a wetted finger.

‘Looking for inspiration, Sergeant?’ Sharpe asked.

‘I am not, sir,’ Colquhoun answered respectfully, but somehow managed to convey that the question was still impertinent. He dabbed a finger on his tongue and carefully turned another page.

So much for that bloody conversation, Sharpe thought. Somewhere ahead, beyond the tall plants that grew higher than a man, another cannon fired. The discharge was muffled by the thick stems. A horse neighed, but Sharpe could not see the beast. He could see nothing through the high crops.

‘Are you going to read us a story, Sergeant?’ Corporal McCallum asked. He spoke in English instead of Gaelic, which meant that he wanted Sharpe to hear.

‘I am not, John. I am not.’

‘Go on, Sergeant,’ McCallum said. ‘Read us one of those dirty tales about tits.’

The men laughed, glancing at Sharpe to see if he was offended. One of the sleeping men jerked awake and looked about him, startled, then muttered a curse, slapped at a fly and lay back. The other soldiers of the company dangled their boots towards the ditch’s crazed mud bed that was decorated with a filigree of dried green scum. A dead lizard lay in one of the dry fissures. Sharpe wondered how the carrion birds had missed it.

‘The laughter of fools, John McCallum,’ Sergeant Colquhoun said, ‘is like the crackling of thorns under the pot.’

‘Away with you, Sergeant!’ McCallum said. ‘I heard it in the kirk once, when I was a wee kid, all about a woman whose tits were like bunches of grapes.’ McCallum twisted to look at Sharpe. ‘Have you ever seen tits like grapes, Mister Sharpe?’

‘I never met your mother, Corporal,’ Sharpe said.

The men laughed again. McCallum scowled. Sergeant Colquhoun lowered his Bible and peered at the Corporal. ‘The Song of Solomon, John McCallum,’ Colquhoun said, ‘likens a woman’s bosom to clusters of grapes, and I have no doubt it refers to the garments that modest women wore in the Holy Land. Perhaps their bodices possessed balls of knotted wool as decoration? I cannot see it is a matter for your merriment.’ Another cannon fired, and this time a round shot whipped through the tall plants close to the ditch. The stems twitched violently, discharging a cloud of dust and small birds into the cloudless sky. The birds flew about in panic for a few seconds, then returned to the swaying seedheads.

‘I knew a woman who had lumpy tits,’ Private Hollister said. He was a dark-jawed, violent man who spoke rarely. ‘Lumpy like a coal sack, they were.’ He frowned at the memory, then shook his head. ‘She died.’

‘This conversation is not seemly,’ Colquhoun said quietly, and the men shrugged and fell silent.

Sharpe wanted to ask the Sergeant about the clusters of grapes, but he knew such an enquiry would only cause ribaldry among the men and, as an officer, Sharpe could not risk being made to look a fool. All the same, it sounded odd to him. Why would anyone say a woman had tits like a bunch of grapes? Grapes made him think of grapeshot and he wondered if the bastards up ahead were equipped with canister. Well, of course they were, but there was no point in wasting canister on a field of bulrushes. Were they bulrushes? It seemed a strange thing for a farmer to grow, but India was full of oddities. There were naked sods who claimed to be holy men, snake-charmers who whistled up hooded horrors, dancing bears draped in tinkling bells, and contortionists draped in bugger all, a right bloody circus. And the clowns ahead would have canister. They would wait till they saw the redcoats, then load up the tin cans that burst like duckshot from the gun barrels. For what we are about to receive among the bulrushes, Sharpe thought, may the Lord make us truly thankful.

‘I’ve found it,’ Colquhoun said gravely.

‘Found what?’ Sharpe asked.

‘I was fairly sure in my mind, sir, that the good book mentioned millet. And so it does. Ezekiel, the fourth chapter and the ninth verse.’ The Sergeant held the book close to his eyes, squinting at the text. He had a round face, afflicted with wens, like a suet pudding studded with currants. ‘“Take thou also unto thee wheat, and barley,”’ he read laboriously, ‘“and beans, and lentils, and millet, and fitches, and put them in one vessel, and make thee bread thereof.”’ Colquhoun carefully closed his Bible, wrapped it in a scrap of tarred canvas and stowed it in his pouch. ‘It pleases me, sir,’ he explained, ‘if I can find everyday things in the scriptures. I like to see things, sir, and imagine my Lord and Saviour seeing the selfsame things.’

‘But why millet?’ Sharpe asked.

‘These crops, sir,’ Colquhoun said, pointing to the tall stems that surrounded them, ‘are millet. The natives call it jowari, but our name is millet.’ He cuffed the sweat from his face with his sleeve. The red dye of his coat had faded to a dull purple. ‘This, of course,’ he went on, ‘is pearl millet, but I doubt the scriptures mention pearl millet. Not specifically.’

‘Millet, eh?’ Sharpe said. So the tall plants were not bulrushes, after all. They looked like bulrushes, except they were taller. Nine or ten feet high. ‘Must be a bastard to harvest,’ he said, but got no response. Sergeant Colquhoun always tried to ignore swear words.

‘What are fitches?’ McCallum asked.

‘A crop grown in the Holy Land,’ Colquhoun answered. He plainly did not know.

‘Sounds like a disease, Sergeant,’ McCallum said. ‘A bad dose of the fitches. Leads to a course of mercury.’ One or two men sniggered at the reference to syphilis, but Colquhoun ignored the levity.

‘Do you grow millet in Scotland?’ Sharpe asked the Sergeant.

‘Not that I am aware of, sir,’ Colquhoun said ponderously, after reflecting on the question for a few seconds, ‘though I daresay it might be found in the Lowlands. They grow strange things there. English things.’ He turned pointedly away.

And sod you too, Sharpe thought. And where the hell was Captain Urquhart? Where the hell was anybody for that matter? The battalion had marched long before dawn, and at midday they had expected to make camp, but then came a rumour that the enemy was waiting ahead and so General Sir Arthur Wellesley had ordered the baggage to be piled and the advance to continue. The King’s 74th had plunged into the millet, then ten minutes later the battalion was ordered to halt beside the dry ditch while Captain Urquhart rode ahead to speak with the battalion commander, and Sharpe had been left to sweat and wait with the company.

Where he had damn all to do except sweat. Damn all. It was a good company, and it did not need Sharpe. Urquhart ran it well, Colquhoun was a magnificent sergeant, the men were as content as soldiers ever were, and the last thing the company needed was a brand new officer, an Englishman at that, who, just two months before, had been a sergeant.

The men were talking in Gaelic and Sharpe, as ever, wondered if they were discussing him. Probably not. Most likely they were talking about the dancing girls in Ferdapoor, where there had been no mere clusters of grapes, but bloody great naked melons. It had been some sort of festival and the battalion had marched one way and the half-naked girls had writhed in the opposite direction and Sergeant Colquhoun had blushed as scarlet as an unfaded coat and shouted at the men to keep their eyes front. Which had been a pointless order, when a score of undressed bibbis were bobbling down the highway with silver bells tied to their wrists and even the officers were staring at them like starving men seeing a plate of roast beef. And if the men were not discussing women, they were probably grumbling about all the marching they had done in the last weeks, criss-crossing the Mahratta countryside under a blazing sun without a sight or smell of the enemy. But whatever they were talking about they were making damn sure that Ensign Richard Sharpe was left out.

Which was fair enough, Sharpe reckoned. He had marched in the ranks long enough to know that you did not talk to officers, not unless you were spoken to or unless you were a slick-bellied crawling bastard looking for favours. Officers were different, except Sharpe did not feel different. He just felt excluded. I should have stayed a sergeant, he thought. He had increasingly thought that in the last few weeks, wishing he was back in the Seringapatam armoury with Major Stokes. That had been the life! And Simone Joubert, the Frenchwoman who had clung to Sharpe after the battle at Assaye, had gone back to Seringapatam to wait for him. Better to be there as a sergeant, he reckoned, than here as an unwanted officer.

No guns had fired for a while. Perhaps the enemy had packed up and gone? Perhaps they had hitched their painted cannon to their ox teams, stowed the canister in its limbers and buggered off northwards? In which case it would be a quick about-turn, back to the village where the baggage was stored, then another awkward evening in the officers’ mess. Lieutenant Cahill would watch Sharpe like a hawk, adding tuppence to Sharpe’s mess bill for every glass of wine, and Sharpe, as the junior officer, would have to propose the loyal toast and pretend not to see when half the bastards wafted their mugs over their canteens. King over the water. Toasting a dead Stuart pretender to the throne who had died in Roman exile. Jacobites who pretended George III was not the proper King. Not that any of them were truly disloyal, and the secret gesture of passing the wine over the water was not even a real secret, but rather was intended to goad Sharpe into English indignation. Except Sharpe did not give a fig. Old King Cole could have been King of Britain for all Sharpe cared.

Colquhoun suddenly barked orders in Gaelic and the men picked up their muskets, jumped into the irrigation ditch where they formed into four ranks and began trudging northwards. Sharpe, taken by surprise, meekly followed. He supposed he should have asked Colquhoun what was happening, but he did not like to display ignorance, and then he saw that the rest of the battalion was also marching, so plainly Colquhoun had decided number six company should advance as well. The Sergeant had made no pretence of asking Sharpe for permission to move. Why should he? Even if Sharpe did give an order the men automatically looked for Colquhoun’s nod before they obeyed. That was how the company worked; Urquhart commanded, Colquhoun came next, and Ensign Sharpe tagged along like one of the scruffy dogs adopted by the men.

Captain Urquhart spurred his horse back down the ditch. ‘Well done, Sergeant,’ he told Colquhoun, who ignored the praise. The Captain turned the horse, its hooves breaking through the ditch’s crust to churn up clots of dried mud. ‘The rascals are waiting ahead,’ Urquhart told Sharpe.

‘I thought they might have gone,’ Sharpe said.

‘They’re formed and ready,’ Urquhart said, ‘formed and ready.’ The Captain was a fine-looking man with a stern face, straight back and steady nerve. The men trusted him. In other days Sharpe would have been proud to serve a man like Urquhart, but the Captain seemed irritated by Sharpe’s presence. ‘We’ll be wheeling to the right soon,’ Urquhart called to Colquhoun, ‘forming line on the right in two ranks.’

‘Aye, sir.’

Urquhart glanced up at the sky. ‘Three hours of daylight left?’ he guessed. ‘Enough to do the job. You’ll take the left files, Ensign.’

‘Yes, sir,’ Sharpe said, and knew that he would have nothing to do there. The men understood their duty, the corporals would close the files and Sharpe would simply walk behind them like a dog tied to a cart.

There was a sudden crash of guns as a whole battery of enemy cannon opened fire. Sharpe heard the round shots whipping through the millet, but none of the missiles came near the 74th. The battalion’s pipers had started playing and the men picked up their feet and hefted their muskets in preparation for the grim work ahead. Two more guns fired, and this time Sharpe saw a wisp of smoke above the seedheads and he knew that a shell had gone overhead. The smoke trail from the burning fuse wavered in the windless heat as Sharpe waited for the explosion, but none sounded.

‘Cut his fuse too long,’ Urquhart said. His horse was nervous, or perhaps it disliked the treacherous footing in the bottom of the ditch. Urquhart spurred the horse up the bank where it trampled the millet. ‘What is this stuff?’ he asked Sharpe. ‘Maize?’

‘Colquhoun says it’s millet,’ Sharpe said, ‘pearl millet.’

Urquhart grunted, then kicked his horse on towards the front of the company. Sharpe cuffed sweat from his eyes. He wore an officer’s red tail coat with the white facings of the 74th. The coat had belonged to a Lieutenant Blaine who had died at Assaye and Sharpe had purchased the coat for a shilling in the auction of dead officers’ effects, then he had clumsily sewn up the bullet hole in the left breast, but no amount of scrubbing had rid the coat of Blaine’s blood which stained the faded red weave black. He wore his old trousers, the ones issued to him when he was a sergeant, red leather riding boots that he had taken from an Arab corpse in Ahmednuggur, and a tasselled red officer’s sash that he had pulled off a corpse at Assaye. For a sword he wore a light cavalry sabre, the same weapon he had used to save Wellesley’s life at the battle of Assaye. He did not like the sabre much. It was clumsy, and the curved blade was never where you thought it was. You struck with the sword, and just when you thought it would bite home, you found that the blade still had six inches to travel. The other officers carried claymores, big, straight-bladed, heavy and lethal, and Sharpe should have equipped himself with one, but he had baulked at the auction prices.

He could have bought every claymore in the auction if he had wished, but he had not wanted to give the impression of being wealthy. Which he was. But a man like Sharpe was not supposed to have money. He was up from the ranks, a common soldier, gutter-born and gutter-bred, but he had hacked down a half-dozen men to save Wellesley’s life and the General had rewarded Sergeant Sharpe by making him into an officer, and Ensign Sharpe was too canny to let his new battalion know that he possessed a king’s fortune. A dead king’s fortune: the jewels he had taken from the Tippoo Sultan in the blood and smoke-stinking Water Gate at Seringapatam.

Would he be more popular if it was known he was rich? He doubted it. Wealth did not give respectability, not unless it was inherited. Besides, it was not poverty that excluded Sharpe from both the officers’ mess and the ranks alike, but rather that he was a stranger. The 74th had taken a beating at Assaye. Not an officer had been left unwounded, and companies that had paraded seventy or eighty strong before the battle now had only forty to fifty men. The battalion had been ripped through hell and back, and its survivors now clung to each other. Sharpe might have been at Assaye, he might even have distinguished himself on the battlefield, but he had not been through the murderous ordeal of the 74th and so he was an outsider.

‘Line to the right!’ Sergeant Colquhoun shouted, and the company wheeled right and shook itself into a line of two ranks. The ditch had emerged from the millet to join a wide, dry riverbed, and Sharpe looked northwards to see a rill of dirty white gunsmoke on the horizon. Mahratta guns. But a long way away. Now that the battalion was free of the tall crops Sharpe could just detect a small wind. It was not strong enough to cool the heat, but it would waft the gunsmoke slowly away.

‘Halt!’ Urquhart called. ‘Face front!’

The enemy cannon might be far off, but it seemed that the battalion would march straight up the riverbed into the mouths of those guns. But at least the 74th was not alone. The 78th, another Highland battalion, was on their right, and on either side of those two Scottish battalions were long lines of Madrassi sepoys.

Urquhart rode back to Sharpe. ‘Stevenson’s joined.’ The Captain spoke loud enough for the rest of the company to hear. Urquhart was encouraging them by letting them know that the two small British armies had combined. General Wellesley commanded both, though for most of the time he split his forces into two parts, the smaller under Colonel Stevenson, but today the two small parts had combined so that twelve thousand infantry could attack together. But against how many? Sharpe could not see the Mahratta army beyond their guns, but doubtless the bastards were there in force.

‘Which means the 94th’s off to our left somewhere,’ Urquhart added loudly, and some of the men muttered their approval of the news. The 94th was another Scottish regiment, so today there were three Scottish battalions attacking the Mahrattas. Three Scottish and ten sepoy battalions, and most of the Scots reckoned that they could have done the job by themselves. Sharpe reckoned they could too. They may not have liked him much, but he knew they were good soldiers. Tough bastards. He sometimes tried to imagine what it must be like for the Mahrattas to fight against the Scots. Hell, he guessed. Absolute hell. ‘The thing is,’ Colonel McCandless had once told Sharpe, ‘it takes twice as much to kill a Scot as it does to finish off an Englishman.’

Poor McCandless. He had been finished off, shot in the dying moments of Assaye. Any of the enemy might have killed the Colonel, but Sharpe had convinced himself that the traitorous Englishman, William Dodd, had fired the fatal shot. And Dodd was still free, still fighting for the Mahrattas, and Sharpe had sworn over McCandless’s grave that he would take vengeance on the Scotsman’s behalf. He had made the oath as he had dug the Colonel’s grave, getting blisters as he had hacked into the dry soil. McCandless had been a good friend to Sharpe and now, with the Colonel deep buried so that no bird or beast could feast on his corpse, Sharpe felt friendless in this army.

‘Guns!’ A shout sounded behind the 74th. ‘Make way!’

Two batteries of six-pounder galloper guns were being hauled up the dry riverbed to form an artillery line ahead of the infantry. The guns were called gallopers because they were light and were usually hauled by horses, but now they were all harnessed to teams of ten oxen so they plodded rather than galloped. The oxen had painted horns and some had bells about their necks. The heavy guns were all back on the road somewhere, so far back that they would probably be too late to join this day’s party.

The land was more open now. There were a few patches of tall millet ahead, but off to the east there were arable fields and Sharpe watched as the guns headed for that dry grassland. The enemy was watching too, and the first round shots bounced on the grass and ricocheted over the British guns.

‘A few minutes before the gunners bother themselves with us, I fancy,’ Urquhart said, then kicked his right foot out of its stirrup and slid down beside Sharpe. ‘Jock!’ He called a soldier. ‘Hold onto my horse, will you?’ The soldier led the horse off to a patch of grass, and Urquhart jerked his head, inviting Sharpe to follow him out of the company’s earshot. The Captain seemed embarrassed, as was Sharpe, who was not accustomed to such intimacy with Urquhart. ‘D’you use a cigar, Sharpe?’ the Captain asked.