Полная версия:

Rebel

BERNARD CORNWELL

The Starbuck Chronicles

Rebel

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1993

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 1993

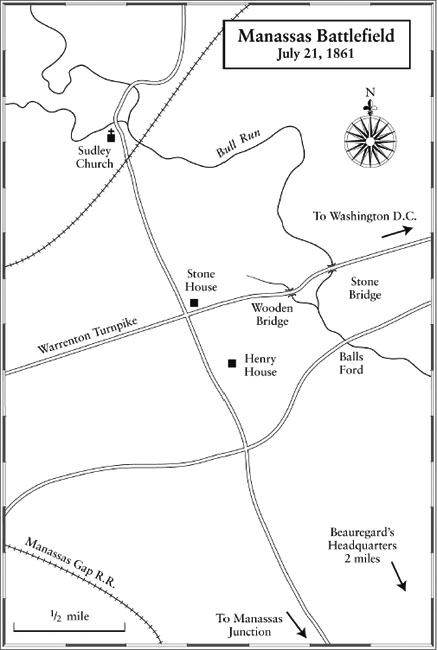

Map © John Gilkes 2013

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007497966

Ebook Edition © September 2013 ISBN: 9780007339471

Version: 2017-05-08

REBEL

is for Alex and Kathy de Jonge,

who introduced me to the Old Dominion

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Part Two

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Part Three

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Historical Note

About the Author

Also by Bernard Cornwell

About the Publisher

ONE

THE YOUNG MAN was trapped at the top end of Shockoe Slip where a crowd had gathered in Cary Street. The young man had smelt the trouble in the air and had tried to avoid it by ducking into an alleyway behind Kerr’s Tobacco Warehouse, but a chained guard dog had lunged at him and so driven him back to the steep cobbled slip where the crowd had engulfed him.

‘You going somewhere, mister?’ a man accosted him.

The young man nodded, but said nothing. He was young, tall and lean, with long black hair and a clean-shaven face of flat planes and harsh angles, though at present his handsome looks were soured by sleeplessness. His skin was sallow, accentuating his eyes, which were the same gray as the fog-wrapped sea around Nantucket, where his ancestors had lived. In one hand he was carrying a stack of books tied with hemp rope, while in his other was a carpetbag with a broken handle. His clothes were of good quality, but frayed and dirty like those of a man well down on his luck. He betrayed no apprehension of the crowd, but instead seemed resigned to their hostility as just another cross he had to bear.

‘You heard the news, mister?’ The crowd’s spokesman was a bald man in a filthy apron that stank of a tannery.

Again the young man nodded. He had no need to ask what news, for there was only one event that could have sparked this excitement in Richmond’s streets. Fort Sumter had fallen, and the news, hopes and fears of civil war were whipping across the American states.

‘So where are you from?’ the bald man demanded, seizing the young man’s sleeve as though to force an answer.

‘Take your hands off me!’ The tall young man had a temper.

‘I asked you civil,’ the bald man said, but nevertheless let go of the younger man’s sleeve.

The young man tried to turn away, but the crowd pressed around him too thickly and he was forced back across the street toward the Columbian Hotel where an older man dressed in respectable though disheveled clothes had been tied to the cast-iron palings that protected the hotel’s lower windows. The young man was still not the crowd’s prisoner, but neither was he free unless he could somehow satisfy their curiosity.

‘You got papers?’ another man shouted in his ear.

‘Lost your voice, son?’ The breath of his questioners was fetid with whiskey and tobacco. The young man made another effort to push against his persecutors, but there were too many of them and he was unable to prevent them from trapping him against a hitching post on the hotel’s sidewalk. It was mid-morning on a warm spring day. The sky was cloudless, though the dark smoke from the Tredegar Iron Works and the Gallegoe Mills and the Asa Snyder Stove Factory and the tobacco factories and Talbott’s Foundry and the City Gas Works all combined to make a rank veil that haloed the sun. A Negro teamster, driving an empty wagon up from the wharves of Samson and Pae’s Foundry, watched expressionless from atop his wagon’s box. The crowd had stopped the carter from turning his horses out of Shockoe Slip, but the man was too wise to make any protest.

‘Where are you from, boy?’ The bald tanner thrust his face close to the young man’s. ‘What’s your name?’

‘None of your business.’ The tone was defiant.

‘So we’ll find out!’ The bald man seized the bundle of books and tried to pull them away. For a moment there was a fruitless tug of war, then the frayed rope holding the books parted and the volumes spilt across the cobbles. The bald man laughed at the accident and the young man hit him. It was a good hard blow and it caught the bald man off his balance so that he rocked backward and almost fell.

Someone cheered the young man, admiring his spirit. There were about two hundred people in the crowd with some fifty more onlookers who half hung back from the proceedings and half encouraged them. The crowd itself was mischievous rather than ugly, like children given an unexpected vacation from school. Most of them were in working clothes, betraying that they had used the news of Fort Sumter’s fall as an excuse to leave their benches and lathes and presses. They wanted some excitement, and errant Northerners caught in the city’s streets would be this day’s best providers of that excitement.

The bald man rubbed his face. He had lost dignity in front of his friends and wanted revenge. ‘I asked you a question, boy.’

‘And I said it was not your business.’ The young man was trying to pick up his books, though two or three had already been snatched away. The prisoner already tied to the hotel’s window bars watched in silence.

‘So where are you from, boy?’ a tall man asked, but in a conciliatory voice, as though he was offering the young man a chance to make a dignified escape.

‘Faulconer Court House.’ The young man heard and accepted the note of conciliation. He guessed that other strangers had been accosted by this mob, then questioned and released, and that if he kept his head then he too might be spared whatever fate awaited the middle-aged man already secured to the railings.

‘Faulconer Court House?’ the tall man asked.

‘Yes.’

‘Your name?’

‘Baskerville.’ He had just read the name on a fascia board of a shop across the street; ‘Bacon and Baskerville,’ the board read, and the young man snatched the name in relief. ‘Nathaniel Baskerville.’ He embellished the lie with his real Christian name.

‘You don’t sound like a Virginian, Baskerville,’ the tall man said.

‘Only by adoption.’ His vocabulary, like the books he had been carrying, betrayed that the young man was educated.

‘So what do you do in Faulconer County, boy?’ another man asked.

‘I work for Washington Faulconer.’ Again the young man spoke defiantly, hoping the name would serve as a talisman for his protection.

‘Best let him go, Don!’ a man called.

‘Let him be!’ a woman intervened. She did not care that the boy was claiming the protection of one of Virginia’s wealthiest landowners; rather she was touched by the misery in his eyes as well as by the unmistakable fact that the crowd’s captive was very good-looking. Women had always been quick to notice Nathaniel, though he himself was too inexperienced to realize their interest.

‘You’re a Yankee, boy, aren’t you?’ the taller man challenged.

‘Not any longer.’

‘So how long have you been in Faulconer County?’ That was the tanner again.

‘Long enough.’ The lie was already losing its cohesion. Nathaniel had never visited Faulconer County, though he had met the county’s richest inhabitant, Washington Faulconer, whose son was his closest friend.

‘So what town lies halfway between here and Faulconer Court House?’ the tanner, still wanting revenge, demanded of him.

‘Answer him!’ the tall man snapped.

Nathaniel was silent, betraying his ignorance.

‘He’s a spy!’ a woman whooped.

‘Bastard!’ The tanner moved in fast, trying to kick Nathaniel, but the young man saw the kick coming and stepped to one side. He slapped a fist at the bald man, clipping an ear, then drove his other hand at the man’s ribs. It was like hitting a hog carcass for all the good it did. Then a dozen hands were mauling and hitting Nathaniel; a fist smacked into his eye and another bloodied his nose to hurl him back hard against the hotel’s wall. His carpetbag was stolen, his books were finally gone, and now a man tore open his coat and ripped his pocket book free. Nathaniel tried to stop that theft, but he was overwhelmed and helpless. His nose was bleeding and his eye swelling. The Negro teamster watched expressionless and did not even betray any reaction when a dozen men commandeered his wagon and insisted he jump down from the box. The men clambered aboard the vehicle and shouted they were going to Franklin Street where a gang was mending the road. The crowd parted to let the wagon turn while the carter, unregarded, edged his way to the crowd’s fringe before running free.

Nathaniel had been thrust against the window bars. His hands were jerked down hard across the bar’s spiked tops and tied with rope to the iron cage. He watched as one of his books was kicked into the gutter, its spine broken and its pages fluttering free. The crowd tore apart his carpetbag, but found little of value except a razor and two more books.

‘Where are you from?’ The middle-aged man who was Nathaniel’s fellow prisoner must have been a very dignified figure before the jeering crowd had dragged him to the railings. He was a portly man, balding, and wearing an expensive broadcloth coat.

‘I come from Boston.’ Nathaniel tried to ignore a drunken woman who pranced mockingly in front of him, brandishing her bottle. ‘And you, sir?’

‘Philadelphia. I only planned to be here for a few hours. I left my traps at the railroad depot and thought I’d look around the city. I have an interest in church architecture, you see, and wanted to see St. Paul’s Episcopal.’ The man shook his head sorrowfully, then flinched as he looked at Nathaniel again. ‘Is your nose broken?’

‘I don’t think so.’ The blood from his nostrils was salty on Nathaniel’s lips.

‘You’ll have a rare black eye, son. But I enjoyed seeing you fight. Might I ask your profession?’

‘I’m a student, sir. At Yale College. Or I was.’

‘My name is Doctor Morley Burroughs. I’m a dentist.’

‘Starbuck, Nathaniel Starbuck.’ Nathaniel Starbuck saw no need to hide his name from his fellow captive.

‘Starbuck!’ The dentist repeated the name in a tone that implied recognition. ‘Are you related?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then I pray they don’t discover it,’ the dentist said grimly.

‘What are they going to do to us?’ Starbuck could not believe he was in real danger. He was in the plumb center of an American town in broad daylight! There were constables nearby, magistrates, churches, schools! This was America, not Mexico or Cathay.

The dentist pulled at his bonds, relaxed, pulled again. ‘From what they’re saying about road menders, son, my guess is tar and feathers, but if they find out you’re a Starbuck?’ The dentist sounded half-hopeful, as though the crowd’s animosity might be entirely diverted onto Starbuck, thus leaving him unscathed.

The drunken woman’s bottle smashed on the roadway. Two other women were dividing Starbuck’s grimy shirts between them while a small bespectacled man was leafing through the papers in Starbuck’s pocket book. There had been little money there, just four dollars, but Starbuck did not fear the loss of his money. Instead he feared the discovery of his name, which was written on a dozen letters in the pocket book. The small man had found one of the letters, which he now opened, read, turned over, then read again. There was nothing private in the letter, it merely confirmed the time of a train on the Penn Central Road, but Starbuck’s name was written in block letters on the letter’s cover and the small man had spotted it. He looked up at Starbuck, then back to the letter, then up at Starbuck yet again. ‘Is your name Starbuck?’ he asked loudly.

Starbuck said nothing.

The crowd smelled excitement and turned back to the prisoners. A bearded man, red-faced, burly and even taller than Starbuck, took up the interrogation. ‘Is your name Starbuck?’

Starbuck looked around, but there was no help in sight. The constables were leaving this mob well alone, and though some respectable-looking people were watching from the high windows of the houses on the far side of Cary Street, none was moving to stop the persecution. A few women looked sympathetically at Starbuck, but they were powerless to help. There was a minister in a frock coat and Geneva bands hovering at the crowd’s edge, but the street was too fired with whiskey and political passion for a man of God to achieve any good, and so the minister was contenting himself with making small ineffective cries of protest that were easily drowned by the raucous celebrants.

‘You’re being asked a question, boy!’ The red-faced man had taken hold of Starbuck’s tie and was twisting it so that the double loop around Starbuck’s throat tightened horribly. ‘Is your name Starbuck?’ He shouted the question, spraying Starbuck’s face with spittle laced with drink and tobacco.

‘Yes.’ There was no point in denying it. The letter was addressed to him, and a score of other pieces of paper in his luggage bore the name, just as his shirts had the fatal name sewn into their neckbands.

‘And are you any relation?’ The man’s face was broken-veined. He had milky eyes and no front teeth. A dribble of tobacco juice ran down his chin and into his brown beard. He tightened the grip on Starbuck’s neck. ‘Any relation, cuffee?’

Again it could not be denied. There was a letter from Starbuck’s father in the pocket book and the letter must be found soon, and so Starbuck did not wait for the revelation, but just nodded assent. ‘I’m his son.’

The man let go of Starbuck’s tie and yelped like a stage red Indian. ‘It’s Starbuck’s son!’ He screamed his victory to the mob. ‘We got ourselves Starbuck’s son!’

‘Oh, Christ in his holy heaven,’ the dentist muttered, ‘but you are in trouble.’

And Starbuck was in trouble, for there were few names more calculated to incense a Southern mob. Abraham Lincoln’s name would have done it well enough, and John Brown’s and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s would have sufficed to inflame a crowd, but lacking those luminaries the name of the Reverend Elial Joseph Starbuck was next best calculated to ignite a blaze of Southern rage.

For the Reverend Elial Starbuck was a famous enemy of Southern aspirations. He had devoted his life to the extirpation of slavery, and his sermons, like his editorials, ruthlessly savaged the South’s slavocracy: mocking its pretensions, flaying its morals, and scorning its arguments. The Reverend Elial’s eloquence in the cause of Negro liberty had made his name famous, not just in America, but wherever Christian men read their journals and prayed to their God, and now, on a day when the news of Fort Sumter’s capture had so inspired the South, a mob in Richmond, Virginia, had taken hold of one of the Reverend Elial Starbuck’s sons.

In truth Nathaniel Starbuck detested his father. He wanted nothing more to do with his father ever again, but the crowd could not know that, nor would they have believed Starbuck if he had told them. This crowd’s mood had turned dark as they demanded revenge on the Reverend Elial Starbuck. They were screaming for that revenge, baying for it. The crowd was also growing as people in the city heard the news about Fort Sumter’s fall and came to join the commotion that celebrated Southern liberty and triumph.

‘String him up!’ a man called.

‘He’s a spy!’

‘Nigger lover!’ A hunk of horse dung sailed toward the prisoners, missing Starbuck, but hitting the dentist on the shoulder.

‘Why couldn’t you have stayed in Boston?’ the dentist complained.

The crowd surged toward the prisoners, then checked, uncertain exactly what they wanted of their captives. A handful of ringleaders had emerged from the crowd’s anonymity, and those ringleaders now shouted for the crowd to be patient. The commandeered wagon had gone to fetch the road menders’ tar, the crowd was assured, and in the meantime a sack of feathers had been fetched from a mattress factory in nearby Virginia Street. ‘We’re going to teach you gennelmen a lesson!’ the big bearded man crowed to the two prisoners. ‘You Yankees think you’re better than us southrons, isn’t that what you think?’ He took a handful of the feathers and scattered them in the dentist’s face. ‘All high and mighty, are you?’

‘I am a mere dentist, sir, who has been practicing my trade in Petersburg.’ Burroughs tried to plead his case with dignity.

‘He’s a dentist!’ the big man shouted delightedly.

‘Pull his teeth out!’

Another cheer announced the return of the borrowed wagon, which now bore on its bed a great black steaming vat of tar. The wagon clattered to a halt close to the two prisoners, and the stench of its tar even overwhelmed the smell of tobacco, which permeated the whole city.

‘Starbuck’s whelp first!’ someone shouted, but it seemed the ceremonies were to be conducted in the order of capture, or else the ringleaders wanted to save the best till last, for Morley Burroughs, the Philadelphia dentist, was the first to be cut free of the bars and dragged toward the wagon. He struggled, but he was no match for the sinewy men who pulled him onto the wagon bed that would now serve as a makeshift stage.

‘Your turn next, Yankee.’ The small bespectacled man who had first discovered Starbuck’s identity had come to stand beside the Bostoner. ‘So what are you doing here?’

The man’s tone had almost been friendly, so Starbuck, thinking he might have found an ally, answered him with the truth. ‘I escorted a lady here.’

‘A lady now! What kind of lady?’ the small man asked. A whore, Starbuck thought bitterly, a cheat, a liar and a bitch, but God, how he had fallen in love with her, and how he had worshiped her, and how he had let her twist him about her little finger and thus ruin his life so that now he was bereft, impoverished and homeless in Richmond. ‘I asked you a question,’ the man insisted.

‘A lady from Louisiana,’ Starbuck answered mildly, ‘who wanted to be escorted from the North.’

‘You’d better pray she comes and saves you quick!’ the bespectacled man laughed, ‘before Sam Pearce gets his hands on you.’

Sam Pearce was evidently the red-faced bearded man who had become the master of ceremonies and who now supervised the stripping away of the dentist’s coat, vest, trousers, shoes, shirt and undershirt, leaving Morley Burroughs humiliated in the sunlight and wearing only his socks and a pair of long drawers, which had been left to him in deference to the modesty of the watching ladies. Sam Pearce now dipped a long-handled ladle into the vat and brought it up dripping with hot treacly tar. The crowd cheered. ‘Give it him, Sam!’

‘Give it him good!’

‘Teach the Yankee a lesson, Sam!’

Pearce plunged the ladle back in the vat and gave the tar a slow stir before lifting the ladle out with its deep bowl heaped high with the smoking, black, treacly substance. The dentist tried to pull away, but two men dragged him toward the vat and bent him over its steaming mouth so that his plump, white, naked back was exposed to the grinning Pearce, who moved the glistening, hot mass of tar over his victim.

The expectant crowd fell silent. The tar hesitated, then flowed off the ladle to strike the back of the dentist‘s balding head. The dentist screamed as the hot thick tar scalded him. He jerked away, but was pulled back, and the crowd, its tension released by his scream, cheered.

Starbuck watched, smelling the thick rank stench of the viscous tar that oozed past the dentist’s ears onto his fat white shoulders. It steamed in the warm spring air. The dentist was crying, whether at the ignominy or for the pain it was impossible to tell, but the crowd didn’t care; all they knew was that a Northerner was suffering, and that gave them pleasure.

Pearce scooped another heavy lump of tar from the vat. The crowd screamed for it to be poured on, the dentist’s knees buckled and Starbuck shivered.

‘You next, boy.’ The tanner had moved to stand beside Starbuck. ‘You next.’ He suddenly swung his fist, burying it in Starbuck’s belly to drive the air explosively out of his lungs and making the young man jerk forward against his bonds. The tanner laughed. ‘You’ll suffer, cuffee, you’ll suffer.’

The dentist screamed again. A second man had leaped onto the wagon to help Pearce apply the tar. The new man used a short-handled spade to heave a mass of thick black tar out of the vat. ‘Save some for Starbuck!’ the tanner shouted.

‘There’s plenty more here, boys!’ The new tormentor slathered his spadeful of tar onto the dentist’s back. The dentist twitched and howled, then was dragged up from his knees as yet more tar was poured down his chest so that it dripped off his belly onto his clean white drawers. Trickles of the viscous substance were dribbling down the sides of his head, down his face and down his back and thighs. His mouth was open and distorted, as though he was crying, but no sound came from him now. The crowd was ribald at the sight of him. One woman was doubled over, helpless with mirth.

‘Where are the feathers?’ another woman called.

‘Make him a chicken, Sam!’

More tar was poured on till the whole of the dentist’s upper body was smothered in the gleaming black substance. His captors had released him, but he was too stricken to try and escape now. Besides, his stockinged feet were stuck in puddles of tar, and all he could do for himself was to try and paw the filthy mess away from his eyes and mouth while his tormentors finished their work. A woman filled her apron with feathers and climbed up to the wagon’s bed where, to huge cheers, the feathers were sprinkled over the humiliated dentist. He stood there, black-draped, feathered, steaming, mouth agape, pathetic, and around him the mob howled and jeered and hooted. Some Negroes on the far sidewalk were convulsed in laughter, while even the minister who had been so pathetically protesting the scene was finding it hard not to smile at the ridiculous spectacle. Sam Pearce, the chief ringleader, released one last handful of feathers to stick in the congealing, cooling tar then stepped back and flourished a proud hand toward the dentist. The crowd cheered again.