Полная версия:

Death of Kings

DEATH OF KINGS

BERNARD CORNWELL

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 2011

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 2011

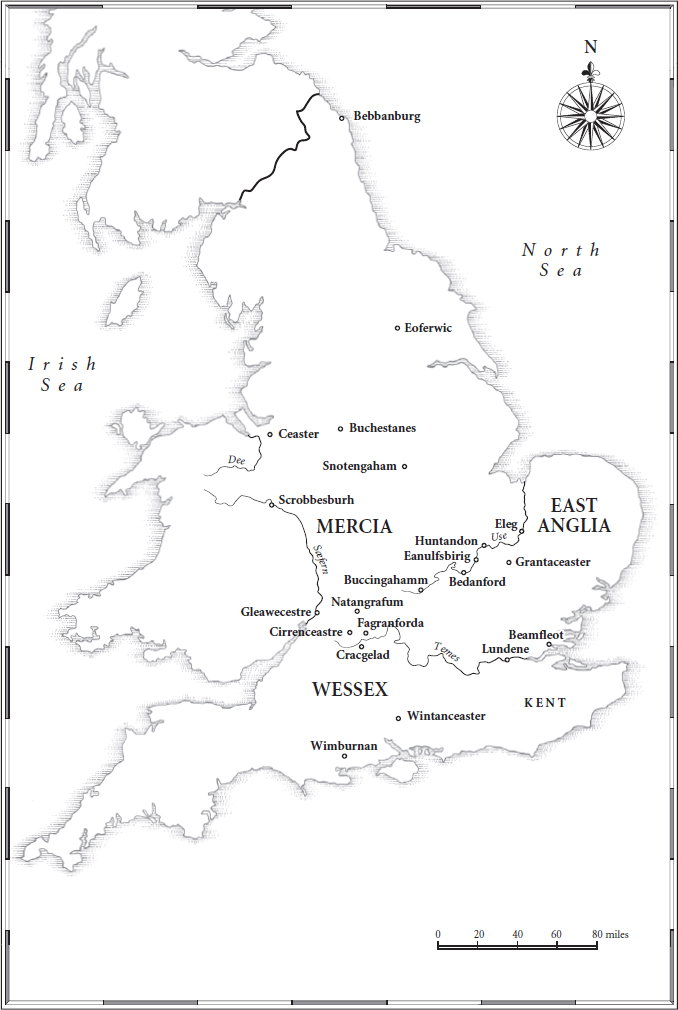

Map © John Gilkes 2011

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007331802

Ebook Edition © September 2011 ISBN: 9780007331826

Version: 2017-05-05

DEATH OF KINGS

is for Anne LeClaire,

Novelist and Friend,

who supplied the first line.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

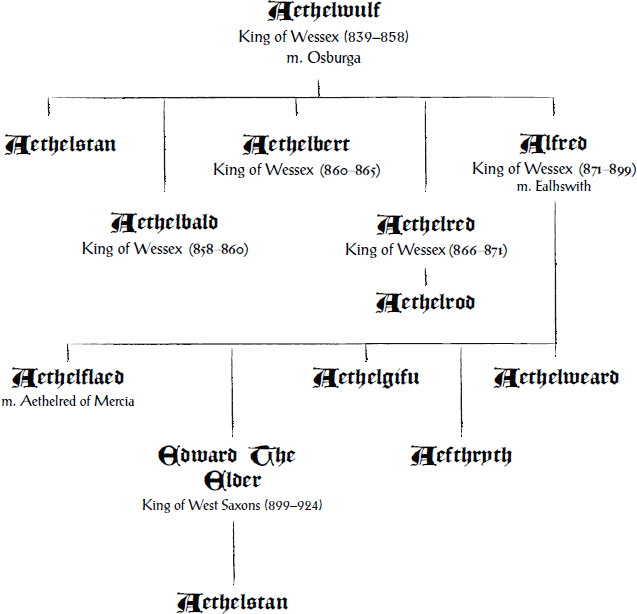

The Royal Family of Wessex

Place Names

Part One: THE SORCERESS

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Two: DEATH OF A KING

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Part Three: ANGELS

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Part Four: DEATH IN WINTER

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Historical Note

About the Author

Also by Bernard Cornwell

About the Publisher

The Royal Family of Wessex

PLACE NAMES

The spelling of place names in Anglo-Saxon England was an uncertain business, with no consistency and no agreement even about the name itself. Thus London was variously rendered as Lundonia, Lundenberg, Lundenne, Lundene, Lundenwic, Lundenceaster and Lundres. Doubtless some readers will prefer other versions of the names listed below, but I have usually employed whichever spelling is cited in either the Oxford or the Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names for the years nearest to AD 900, but even that solution is not foolproof. Hayling Island, in 956, was written as both Heilincigae and Hæglingaiggæ. Nor have I been consistent myself; I should spell England as Englaland, and have preferred the modern form Northumbria to Norðhymbralond to avoid the suggestion that the boundaries of the ancient kingdom coincide with those of the modern county. So this list, like the spellings themselves, is capricious.

Baddan Byrig Badbury Rings, Dorset Beamfleot Benfleet, Essex Bebbanburg Bamburgh, Northumberland Bedanford Bedford, Bedfordshire Blaneford Blandford Forum, Dorset Buccingahamm Buckingham, Bucks Buchestanes Buxton, Derbyshire Ceaster Chester, Cheshire Cent County of Kent Cippanhamm Chippenham, Wiltshire Cirrenceastre Cirencester, Gloucestershire Contwaraburg Canterbury, Kent Cyninges Tun Kingston upon Thames, Greater London Cracgelad Cricklade, Wiltshire Cumbraland Cumberland Cytringan Kettering, Northants Dumnoc Dunwich, Suffolk Dunholm Durham, County Durham Eanulfsbirig St Neot, Cambridgeshire Eleg Ely, Cambridgeshire Eoferwic York, Yorkshire (called Jorvik by the Danes) Exanceaster Exeter, Devon Fagranforda Fairford, Gloucestershire Fearnhamme Farnham, Surrey Fifhidan Fyfield, Wiltshire Fughelness Foulness Island, Essex Gegnesburh Gainsborough, Lincolnshire Gleawecestre Gloucester, Gloucestershire Grantaceaster Cambridge, Cambridgeshire Hothlege, River Hadleigh Ray, Essex Hrofeceastre Rochester, Kent Humbre, River River Humber Huntandon Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire Liccelfeld Lichfield, Staffordshire Lindisfarena Lindisfarne (Holy Island), Northumberland Lundene London Medwæg, River River Medway, Kent Natangrafum Notgrove, Gloucestershire Oxnaforda Oxford, Oxfordshire Ratumacos Rouen, Normandy, France Rochecestre Wroxeter, Shropshire Sarisberie Salisbury, Wiltshire Sæfern River Severn Sceaftesburi Shaftesbury, Dorset Sceobyrig Shoebury, Essex Scrobbesburh Shrewsbury, Shropshire Snotengaham Nottingham, Nottinghamshire Sumorsæte Somerset Temes, River River Thames Thornsæta Dorset Tofeceaster Towcester, Northamptonshire Trente, River River Trent Turcandene Turkdean, Gloucestershire Tweoxnam Christchurch, Dorset Westune Whitchurch, Shropshire Wiltunscir Wiltshire Wimburnan Wimborne, Dorset Wintanceaster Winchester, Hampshire Wygraceaster Worcester, WorcestershirePART ONE

The Sorceress

One

‘Every day is ordinary,’ Father Willibald said, ‘until it isn’t.’ He smiled happily, as though he had just said something he thought I would find significant, then looked disappointed when I said nothing. ‘Every day,’ he started again.

‘I heard your drivelling,’ I snarled.

‘Until it isn’t,’ he finished weakly. I liked Willibald, even if he was a priest. He had been one of my childhood tutors and now I counted him as a friend. He was gentle, earnest, and if the meek ever do inherit the earth then Willibald will be rich beyond measure.

And every day is ordinary until something changes, and that cold Sunday morning had seemed as ordinary as any until the fools tried to kill me. It was so cold. There had been rain during the week, but on that morning the puddles froze and a hard frost whitened the grass. Father Willibald had arrived soon after sunrise and discovered me in the meadow. ‘We couldn’t find your estate last night,’ he explained his early appearance, shivering, ‘so we stayed at Saint Rumwold’s monastery,’ he gestured vaguely southwards. ‘It was cold there,’ he added.

‘They’re mean bastards, those monks,’ I said. I was supposed to deliver a weekly cartload of firewood to Saint Rumwold’s, but that was a duty I ignored. The monks could cut their own timber. ‘Who was Rumwold?’ I asked Willibald. I knew the answer, but wanted to drag Willibald through the thorns.

‘He was a very pious child, lord,’ he said.

‘A child?’

‘A baby,’ he said, sighing as he saw where the conversation was leading, ‘a mere three days old when he died.’

‘A three-day-old baby is a saint?’

Willibald flapped his hands. ‘Miracles happen, lord,’ he said, ‘they really do. They say little Rumwold sang God’s praises whenever he suckled.’

‘I feel much the same when I get hold of a tit,’ I said, ‘so does that make me a saint?’

Willibald shuddered, then sensibly changed the subject. ‘I’ve brought you a message from the ætheling,’ he said, meaning King Alfred’s eldest son, Edward.

‘So tell me.’

‘He’s the King of Cent now,’ Willibald said happily.

‘He sent you all this way to tell me that?’

‘No, no. I thought perhaps you hadn’t heard.’

‘Of course I heard,’ I said. Alfred, King of Wessex, had made his eldest son King of Cent, which meant Edward could practise being a king without doing too much damage because Cent, after all, was a part of Wessex. ‘Has he ruined Cent yet?’

‘Of course not,’ Willibald said, ‘though…’ he stopped abruptly.

‘Though what?’

‘Oh it’s nothing,’ he said airily and pretended to take an interest in the sheep. ‘How many black sheep do you have?’ he asked.

‘I could hold you by the ankles and shake you till the news drops out,’ I suggested.

‘It’s just that Edward, well,’ he hesitated, then decided he had better tell me in case I did shake him by the ankles, ‘it’s just that he wanted to marry a girl in Cent and his father wouldn’t agree. But really that isn’t important!’

I laughed. So young Edward was not quite the perfect heir after all. ‘Edward’s on the rampage, is he?’

‘No, no! Merely a youthful fancy and it’s all history now. His father’s forgiven him.’

I asked nothing more, though I should have paid much more attention to that sliver of gossip. ‘So what is young Edward’s message?’ I asked. We were standing in the lower meadow of my estate in Buccingahamm, which lay in eastern Mercia. It was really Æthelflaed’s land, but she had granted me the food-rents, and the estate was large enough to support thirty household warriors, most of whom were in church that morning. ‘And why aren’t you at church?’ I asked Willibald before he could answer my first question, ‘it’s a feast day, isn’t it?’

‘Saint Alnoth’s Day,’ he said as though that was a special treat, ‘but I wanted to find you!’ He sounded excited. ‘I have King Edward’s news for you. Every day is ordinary…’

‘Until it isn’t,’ I said brusquely.

‘Yes, lord,’ he said lamely, then frowned in puzzlement, ‘but what are you doing?’

‘I’m looking at sheep,’ I said, and that was true. I was looking at two hundred or more sheep that looked back at me and bleated pathetically.

Willibald turned to stare at the flock again. ‘Fine animals,’ he said as if he knew what he was talking about.

‘Just mutton and wool,’ I said, ‘and I’m choosing which ones live and which ones die.’ It was the killing time of the year, the grey days when our animals are slaughtered. We keep a few alive to breed in the spring, but most have to die because there is not enough fodder to keep whole flocks and herds alive through the winter. ‘Watch their backs,’ I told Willibald, ‘because the frost melts fastest off the fleece of the healthiest beasts. So those are the ones you keep alive.’ I lifted his woollen hat and ruffled his hair, which was going grey. ‘No frost on you,’ I said cheerfully, ‘otherwise I’d have to slit your throat.’ I pointed to a ewe with a broken horn, ‘Keep that one!’

‘Got her, lord,’ the shepherd answered. He was a gnarled little man with a beard that hid half his face. He growled at his two hounds to stay where they were, then ploughed into the flock and used his crook to haul out the ewe, then dragged her to the edge of the field and drove her to join the smaller flock at the meadow’s farther end. One of his hounds, a ragged and pelt-scarred beast, snapped at the ewe’s heels until the shepherd called the dog off. The shepherd did not need my help in selecting which animals should live and which must die. He had culled his flocks since he was a child, but a lord who orders his animals slaughtered owes them the small respect of taking some time with them.

‘The day of judgement,’ Willibald said, pulling his hat over his ears.

‘How many’s that?’ I asked the shepherd.

‘Jiggit and mumph, lord,’ he said.

‘Is that enough?’

‘It’s enough, lord.’

‘Kill the rest then,’ I said.

‘Jiggit and mumph?’ Willibald asked, still shivering.

‘Twenty and five,’ I said. ‘Yain, tain, tether, mether, mumph. It’s how shepherds count. I don’t know why. The world is full of mystery. I’m told some folk even believe that a three-day-old baby is a saint.’

‘God is not mocked, lord,’ Father Willibald said, attempting to be stern.

‘He is by me,’ I said, ‘so what does young Edward want?’

‘Oh, it’s most exciting,’ Willibald began enthusiastically, then checked because I had raised a hand.

The shepherd’s two dogs were growling. Both had flattened themselves and were facing south towards a wood. Sleet had begun to fall. I stared at the trees, but could see nothing threatening among the black winter branches or among the holly bushes. ‘Wolves?’ I asked the shepherd.

‘Haven’t seen a wolf since the year the old bridge fell, lord,’ he said.

The hair on the dogs’ necks bristled. The shepherd quietened them by clicking his tongue, then gave a short sharp whistle and one of the dogs raced away towards the wood. The other whined, wanting to be let loose, but the shepherd made a low noise and the dog went quiet again.

The running dog curved towards the trees. She was a bitch and knew her business. She leaped an ice-skimmed ditch and vanished among the holly, barked suddenly, then reappeared to jump the ditch again. For a moment she stopped, facing the trees, then began running again just as an arrow flitted from the wood’s shadows. The shepherd gave a shrill whistle and the bitch raced back towards us, the arrow falling harmlessly behind her.

‘Outlaws,’ I said.

‘Or men looking for deer,’ the shepherd said.

‘My deer,’ I said. I still gazed at the trees. Why would poachers shoot an arrow at a shepherd’s dog? They would have done better to run away. So maybe they were really stupid poachers?

The sleet was coming harder now, blown by a cold east wind. I wore a thick fur cloak, high boots and a fox-fur hat, so did not notice the cold, but Willibald, in priestly black, was shivering despite his woollen cape and hat. ‘I must get you back to the hall,’ I said. ‘At your age you shouldn’t be outdoors in winter.’

‘I wasn’t expecting rain,’ Willibald said. He sounded miserable.

‘It’ll be snow by midday,’ the shepherd said.

‘You have a hut near here?’ I asked him.

He pointed north. ‘Just beyond the copse,’ he said. He was pointing at a thick stand of trees through which a path led.

‘Does it have a fire?’

‘Yes, lord.’

‘Take us there,’ I said. I would leave Willibald beside the fire and fetch him a proper cloak and a docile horse to get him back to the hall.

We walked north and the dogs growled again. I turned to look south and suddenly there were men at the wood’s edge. A ragged line of men who were staring at us. ‘You know them?’ I asked the shepherd.

‘They’re not from around here, lord, and eddera-a-dix,’ he said, meaning there were thirteen of them, ‘that’s unlucky, lord.’ He made the sign of the cross.

‘What…’ Father Willibald began.

‘Quiet,’ I said. The shepherd’s two dogs were snarling now. ‘Outlaws,’ I guessed, still looking at the men.

‘Saint Alnoth was murdered by outlaws,’ Willibald said worriedly.

‘So not everything outlaws do is bad,’ I said, ‘but these ones are idiots.’

‘Idiots?’

‘To attack us,’ I said. ‘They’ll be hunted down and ripped apart.’

‘If we are not killed first,’ Willibald said.

‘Just go!’ I pushed him towards the northern trees and touched a hand to my sword hilt before following him. I was not wearing Serpent-Breath, my great war sword, but a lesser, lighter blade that I had taken from a Dane I had killed earlier that year in Beamfleot. It was a good sword, but at that moment I wished I had Serpent-Breath strapped around my waist. I glanced back. The thirteen men were crossing the ditch to follow us. Two had bows. The rest seemed to be armed with axes, knives or spears. Willibald was slow, already panting. ‘What is it?’ he gasped.

‘Bandits?’ I suggested. ‘Vagrants? I don’t know. Run!’ I pushed him into the trees, then slid the sword from its scabbard and turned to face my pursuers, one of whom took an arrow from the bag strapped at his waist. That persuaded me to follow Willibald into the copse. The arrow slid past me and ripped through the undergrowth. I wore no mail, only the thick fur cloak that offered no protection from a hunter’s arrow. ‘Keep going,’ I shouted at Willibald, then limped up the path. I had been wounded in the right thigh at the battle of Ethandun and though I could walk and could even run slowly, I knew I would not be able to outpace the men who were now within easy bowshot behind me. I hurried up the path as a second arrow was deflected by a branch and tumbled noisily through the trees. Every day is ordinary, I thought, until it gets interesting. My pursuers could not see me among the dark trunks and thick holly bushes, but they assumed I had followed Willibald and so kept to the path while I crouched in the thick undergrowth, concealed by the glossy leaves of a holly bush and by my cloak that I had pulled over my fair hair and face. The pursuers went past my hiding place without a glance. The two archers were in front.

I let them get well ahead, then followed. I had heard them speak as they passed and knew they were Saxons and, by their accents, probably from Mercia. Robbers, I assumed. A Roman road passed through deep woods nearby and masterless men haunted the woods to ambush travellers who, to protect themselves, went in large groups. I had twice led my warriors on hunts for such bandits and thought I had persuaded them to make their living far from my estate, but I could not think who else these men could be. Yet it was not like such vagrants to invade an estate. The hair at the back of my neck still prickled.

I moved cautiously as I approached the edge of the trees, then saw the men beside the shepherd’s hut that resembled a heap of grass. He had made the hovel with branches covered by turf, leaving a hole in the centre for the smoke of his fire to escape. There was no sign of the shepherd himself, but Willibald had been captured, though so far he was unhurt, protected, perhaps, by his status as a priest. One man held him. The others must have realised I was still in the trees, because they were staring towards the copse that hid me.

Then, suddenly, the shepherd’s two dogs appeared from my left and ran howling towards the thirteen men. The dogs ran fast and lithe, circling the group and sometimes leaping towards them and snapping their teeth before sheering away. Only one man had a sword, but he was clumsy with the blade, swinging it at the bitch as she came close and missing her by an arm’s length. One of the two bowmen put a string on his cord. He hauled the arrow back, then suddenly fell backwards as if struck by an invisible hammer. He sprawled on the turf as his arrow flitted into the sky and fell harmlessly into the trees behind me. The dogs, down on their front paws now, bared their teeth and growled. The fallen archer stirred, but evidently could not stand. The other men looked scared.

The second archer raised his stave, then recoiled, dropping the bow to clap his hands to his face and I saw a spark of blood there, blood bright as the holly berries. The splash of colour showed in the winter morning, then it was gone and the man was clutching his face and bending over in pain. The hounds barked, then loped back into the trees. The sleet was falling harder, loud as it struck the bare branches. Two of the men moved towards the shepherd’s cottage, but were called back by their leader. He was younger than the others and looked more prosperous, or at least less poor. He had a thin face, darting eyes and a short fair beard. He wore a scarred leather jerkin, but beneath it I could see a mail coat. So he had either been a warrior or else had stolen the mail. ‘Lord Uhtred!’ he called.