Полная версия:

Battle Flag

Bernard Cornwell

BATTLE FLAG

THE NATHANIEL STARBUCK CHRONICLES

BOOK THREE

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.harpercollins.co.uk

This book is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents, and dialogue are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

The right of Bernard Cornwell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

BATTLE FLAG. Copyright © 2006 by Bernard Cornwell. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

EPub Edition © JULY 2009 ISBN: 9780007339495

06 07 08 09 10

Version: 2017-05-08

Praise for Bernard Cornwell’s THE NATHANIEL STARBUCK CHRONICLES

“The most entertaining military historical novels…. Always based on fact, always interesting…always entertaining.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“[A] wonderful series…believable, three-dimensional characters…. A rollicking treat for Cornwell’s many fans.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Highly successful.”

—The Times (London)

“Fast-paced and exciting…. Cornwell—and Starbuck—don’t disappoint.”

—Birmingham News

“A top-class read by a master of historical drama. Nate Starbuck is on the march, and on his way to fame.”

—Irish Press

Battle Flag is for my father, with love

CONTENTS

COVER PAGE

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

PRAISE

DEDICATION

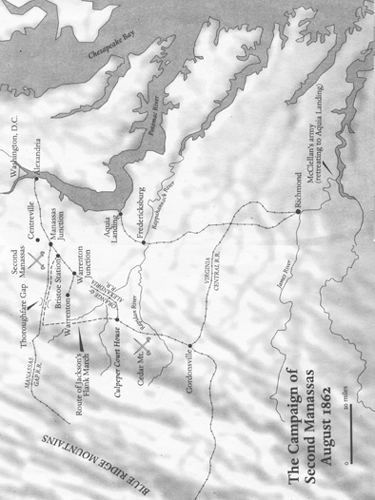

MAP

PART ONE

CAPTAIN NATHANIEL STARBUCK FIRST SAW HIS NEW

THE YANKEE CAVALRY PATROL REACHED GENERAL

IT’S GOD’S WILL, BANKS! GOD’S WILL!” THE REVEREND

SATURDAY MORNING, THE DAY AFTER BATTLE, AGAIN

PART TWO

JACKSON, LIKE A SNAKE THAT HAD STRUCK, HURT, BUT

THERE WERE TIMES WHEN GENERAL WASHINGTON

THE YANKEES’ SPRING OFFENSIVE MIGHT HAVE FAILED,

GENERAL STUART’S AIDE REACHED LEE’S HEADQUARTERS

THEY MARCHED LIKE THEY HAD NEVER MARCHED IN

THE LEGION MARCHED INTO BRISTOE JUST AS THE TRAIN

ALL DAY THE YANKEES TRIED TO MAKE SENSE OF

AT MANASSAS, ON FRIDAY AUGUST 29, 1862, THE

THE LAST NORTHERN ATTACK OF THE DAY WAS BY FAR

THE FIRST ATTACK OF THE SATURDAY MORNING WAS AN

HISTORICAL NOTE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

OTHER BOOKS BY BERNARD CORNWELL

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Map

CAPTAIN NATHANIEL STARBUCK FIRST SAW HIS NEW commanding general when the Faulconer Legion forded the Rapidan. Thomas Jackson was on the river’s northern bank, where he appeared to be in a trance, for he was motionless in his saddle with his left hand held high in the air while his eyes, blue and resentful, stared into the river’s vacant and murky depths. His glum stillness was so uncanny that the marching column edged to the far margin of the ford rather than pass near a man whose stance so presaged death. The General’s physical appearance was equally disturbing. Jackson had a ragged beard, a plain coat, and a dirty cap, while his horse looked as if it should have been taken to a slaughterhouse long before. It was hard to credit that this was the South’s most controversial general, the man who gave the North sleepless nights and nervous days, but Lieutenant Franklin Coffman, sixteen years old and newly arrived in the Faulconer Legion, asserted that the odd-looking figure was indeed the famous Stonewall Jackson. Coffman had once been taught by Professor Thomas Jackson. “Mind you,” Lieutenant Coffman confided in Starbuck, “I don’t believe generals make any real difference to battles.”

“Such wisdom in one so young,” said Starbuck, who was twenty-two years old.

“It’s the men who win battles, not generals,” Coffman said, ignoring his Captain’s sarcasm. Lieutenant Coffman had received one year’s schooling at the Virginia Military Institute, where Thomas Jackson had ineffectively lectured him in artillery drill and Natural Philosophy. Now Coffman looked at the rigid figure sitting motionless in the shabby saddle. “I can’t imagine old Square Box as a general,” Coffman said scornfully. “He couldn’t keep a schoolroom in order, let alone an army.”

“Square Box?” Starbuck asked. General Jackson had many nicknames. The newspapers called him Stonewall, his soldiers called him Old Jack or even Old Mad Jack, while many of Old Jack’s former students liked to refer to him as Tom Fool Jack, but Square Box was a name new to Starbuck.

“He’s got the biggest feet in the world,” Coffman explained. “Really huge! And the only shoes that ever fitted him were like boxes.”

“What a fount of useful information you are, Lieutenant,” Starbuck said casually. The Legion was still too far from the river for Starbuck to see the General’s feet, but he made a mental note to look at these prodigies when he did finally reach the Rapidan. The Legion was presently not moving at all, its progress halted by the reluctance of the men ahead to march straight through the ford without first removing their tattered boots. Mad Jack Stonewall Square Box Jackson was reputed to detest such delays, but he seemed oblivious to this holdup. Instead he just sat, hand in the air and eyes on the river, while right in front of him the column bunched and halted. The men behind the obstruction were grateful for the enforced halt, for the day was blistering hot, the air motionless, and the heat as damp as steam. “You were remarking, Coffman, on the ineffectiveness of generals?” Starbuck prompted his new junior officer.

“If you think about it, sir,” Coffman said with a youthful passion, “we haven’t got any real generals, not like the Yankees, but we still win battles. I reckon that’s because the Southerner is unbeatable.”

“What about Robert Lee?” Starbuck asked. “Isn’t he a real general?”

“Lee’s old! He’s antediluvian!” Coffman said, shocked that Starbuck should even have suggested the name of the new commander of the Army of Northern Virginia. “He must be fifty-five, at least!”

“Jackson’s not old,” Starbuck pointed out. “He isn’t even forty yet.”

“But he’s mad, sir. Honest! We used to call him Tom Fool.”

“He must be mad then,” Starbuck teased Coffman. “So why do we win battles despite having mad generals, ancient generals, or no generals at all?”

“Because fighting is in the Southern blood, sir. It really is.” Coffman was an eager young man who was determined to be a hero. His father had died of consumption, leaving his mother with four young sons and two small daughters. His father’s death had forced Coffman to leave the Virginia Military Institute after his first year, but that one year’s military schooling had equipped him with a wealth of martial theories. “Northerners,” he now explained to Starbuck, “have diluted blood. There are too many immigrants in the North, sir. But the South has pure blood, sir. Real American blood.”

“You mean the Yankees are an inferior race?”

“It’s an acknowledged fact, sir. They’ve lost the thoroughbred strain, sir.”

“You do know I’m a Yankee, Coffman, don’t you?” Starbuck asked.

Coffman immediately looked confused, though before he could frame any response he was interrupted by Colonel Thaddeus Bird, the Faulconer Legion’s commanding officer, who came striding long-legged from the rear of the stalled column. “Is that really Jackson?” Bird asked, gazing across the river.

“Lieutenant Coffman informs me that the General’s real name is Old Mad Tom Fool Square Box Jackson, and that is indeed the man himself,” Starbuck answered.

“Ah, Coffman,” Bird said, peering down at the small Lieutenant as though Coffman was some curious specimen of scientific interest, “I remember when you were nothing but a chirruping infant imbibing the lesser jewels of my glittering wisdom.” Bird, before he became a soldier, had been the schoolmaster in Faulconer Court House, where Coffman’s family lived.

“Lieutenant Coffman has not ceased to imbibe wisdom,” Starbuck solemnly informed Colonel Bird, “nor indeed to impart it, for he has just informed me that we Yankees are an inferior breed, our blood being soured, tainted, and thinned by the immigrant strain.”

“Quite right, too!” Bird said energetically; then the Colonel draped a thin arm around the diminutive Coffman’s shoulders. “I could a tale unfold, young Coffman, whose lightest word would harrow up thy soul, freeze thy young blood, and make thy two eyes, like stars, start from their spheres.” He spoke even more closely into the ear of the astonished Lieutenant. “Did you know, Coffman, that the very moment an immigrant boat docks in Boston all the Beacon Hill families send their wives down to the harbor to be impregnated? Is that not the undeniable truth, Starbuck?”

“Indeed it is, sir, and they send their daughters as well if the boat arrives on the Sabbath.”

“Boston is a libidinous town, Coffman,” Bird said very sternly as he stepped away from the wide-eyed Lieutenant, “and if I am to give you just one piece of advice in this sad bad world, then let it be to avoid the place. Shun it, Coffman! Regard Boston as you might regard Sodom or Gomorrah. Remove it from your catalog of destinations. Do you understand me, Coffman?”

“Yes, sir,” Coffman said very seriously.

Starbuck laughed at the look on his Lieutenant’s face. Coffman had arrived the day before with a draft of conscripted men to replace the casualties of Gaines’ Mill and Malvern Hill. The conscripts had mostly been culled from the alleys of Richmond and, to Starbuck, appeared to be a scrawny, unhealthy, and shifty-looking crew of dubious reliability, but Franklin Coffman, like the original members of the Legion, was a volunteer from Faulconer County and full of enthusiasm for the Southern cause.

Colonel Bird now abandoned his teasing of the Lieutenant and plucked at Starbuck’s sleeve. “Nate,” he said, “a word.” The two men walked away from the road, crossing a shallow ditch into a meadow that was wan and brown from the summer’s heat wave. Starbuck limped, not because he was wounded, but because the sole of his right boot was becoming detached from its uppers. “Is it me?” Bird asked as the two men paced across the dry grass. “Am I getting wiser or is it that the young are becoming progressively more stupid? And young Coffman, believe it if you will, was brighter than most of the infants it was my misfortune to teach. I remember he mastered the theory of gerunds in a single morning!”

“I’m not sure I ever mastered gerunds,” Starbuck said.

“Hardly difficult,” Bird said, “so long as you remember that they are nouns which provide—”

“And I’m not sure I ever want to master the damn things,” Starbuck interrupted.

“Wallow in your ignorance, then,” Bird said grandly. “But you’re also to look after young Coffman. I couldn’t bear to write to his mother and tell her he’s dead, and I have a horrid feeling that he’s likely to prove stupidly brave. He’s like a puppy. Tail up, nose wet, and can’t wait to play battles with Yankees.”

“I’ll look after him, Pecker.”

“But you’re also to look after yourself,” Bird said meaningfully. He stopped and looked into Starbuck’s eyes. “There’s a rumor, only a rumor, and God knows I do not like passing on rumors, but this one has an unpleasant ring to it. Swynyard was heard to say that you won’t survive the next battle.”

Starbuck dismissed the prediction with a grin. “Swynyard’s a drunk, not a prophet.” Nevertheless he felt a shudder of fear. He had been a soldier long enough to become inordinately superstitious, and no man liked to hear a presentiment of his own death.

“Suppose,” Bird said, taking two cigars from inside his hatband, “that Swynyard has decided to arrange it?”

Starbuck stared incredulously at his Colonel. “Arrange my death?” he finally asked.

Bird scratched a lucifer match alight and stooped over its flame. “Colonel Swynyard,” he announced dramatically when his cigar was drawing properly, “is a drunken swine, a beast, a cream-faced loon, a slave of nature, and a son of hell, but he is also, Nate, a most cunning rogue, and when he is not in his cups he must realize that he is losing the confidence of our great and revered leader. Which is why he must now try to do something which will please our esteemed lord and master. Get rid of you.” The last four words were delivered brutally.

Starbuck laughed them off. “You think Swynyard will shoot me in the back?”

Bird gave Starbuck the lit cigar. “I don’t know how he’ll kill you. All I know is that he’d like to kill you, and that Faulconer would like him to kill you, and for all I know our esteemed General is prepared to award Swynyard a healthy cash bonus if he succeeds in killing you. So be careful, Nate, or else join another regiment.”

“No,” Starbuck said immediately. The Faulconer Legion was his home. He was a Bostonian, a Northerner, a stranger in a strange land who had found in the Legion a refuge from his exile. The Legion provided Starbuck with casual kindnesses and a hive of friends, and those bonds of affection were far stronger than the distant enmity of Washington Faulconer. That enmity had grown worse when Faulconer’s son Adam had deserted from the Southern army to fight for the Yankees, a defection for which Brigadier General Faulconer blamed Captain Starbuck, but not even the disparity in their ranks could persuade Starbuck to abandon his fight against the man who had founded the Legion and who now commanded the five regiments, including the Legion, that made up the Faulconer Brigade. “I’ve got no need to run away,” he now told Bird. “Faulconer won’t last any longer than Swynyard. Faulconer’s a coward and Swynyard’s a drunk, and before this summer’s out, Pecker, you’ll be Brigade commander and I’ll be in command of the Legion.”

Bird hooted with delight. “You are incorrigibly conceited, Nate. You! Commanding the Legion? I imagine Major Hinton and the dozen other men senior to you might have a different opinion.”

“They might be senior, but I’m the best.”

“Ah, you still suffer from the delusion that merit is rewarded in this world? I suppose you contracted that opinion with all the other nonsense they crammed into you when Yale was failing to give you mastery of the gerund?” Bird, achieving this lick at Starbuck’s alma mater, laughed gleefully. His head jerked back and forth as he laughed, the odd jerking motion explaining his nickname: Pecker. Starbuck joined in the laughter, for he, like just about everyone else in the Legion, liked Bird enormously. The schoolmaster was eccentric, opinionated, contrary, and one of the kindest men alive. He had also proved to possess an unexpected talent for soldiering. “We move at last,” Bird now said, gesturing at the stalled column that had begun edging toward the ford where the solitary, strange figure of Jackson waited motionless on his mangy horse. “You owe me two dollars,” Bird suddenly remarked as he led Starbuck back to the road.

“Two dollars!”

“Major Hinton’s fiftieth birthday approaches. Lieutenant Pine assures me he can procure a ham, and I shall prevail on our beloved leader for some wine. We are paying for a feast.”

“Is Hinton really that old?” Starbuck asked.

“He is indeed, and if you live that long we shall doubtless give you a drunken dinner as a reward. Have you got two bucks?”

“I haven’t got two cents,” Starbuck said. He had some money in Richmond, but that money represented his cushion against disaster and was not for frittering away on ham and wine.

“I shall lend you the money,” Bird said with a rather despairing sigh. Most of the Legion’s officers had private means, but Colonel Bird, like Starbuck, was forced to live on the small wages of a Confederate officer.

The men of Company H stood as Starbuck and Bird approached the road, though one of the newly arrived conscripts stayed prone on the grass verge and complained he could not march another step. His reward was a kick in the ribs from Sergeant Truslow. “You can’t do that to me!” the man protested, scrabbling sideways to escape the Sergeant.

Truslow grabbed the man’s jacket and pulled his face close in to his own. “Listen, you son of a poxed bitch, I can slit your slumbelly guts wide open and sell them to the Yankees for hog food if I want, and not because I’m a sergeant and you’re a private, but because I’m a mean son of a bitch and you’re a lily-livered louse. Now get the hell up and march.”

“What comfortable words the good Sergeant speaks,” Bird said as he jumped back across the dry ditch. He drew on his cigar. “So I can’t persuade you to join another regiment, Nate?”

“No, sir.”

Pecker Bird shook his head ruefully. “I think you’re a fool, Nate, but for God’s sake be a careful fool. For some odd reason I’d be sorry to lose you.”

“Fall in!” Truslow shouted.

“I’ll take care,” Starbuck promised as he rejoined his company. His thirty-six veterans were lean, tanned, and ragged. Their boots were falling to pieces, their gray jackets were patched with common brown cloth, and their worldly possessions were reduced to what a man could carry suspended from his rope belt or sling in a rolled blanket across his shoulder. The twenty conscripts made an awkward contrast in their new uniforms, clumsy leather brogans, and stiff knapsacks. Their faces were pale and their rifle muzzles unblackened by firing. They knew this northward march through the central counties of Virginia probably meant an imminent battle, but what that battle would bring was a mystery, while the veterans knew only too well that a fight would mean screaming and blood and hurt and pain and thirst, but maybe, too, a cache of plundered Yankee dollars or a bag of real coffee taken from a festering, maggot-riddled Northern corpse. “March on!” Starbuck shouted, and fell in beside Lieutenant Franklin Coffman at the head of the company.

“You see if I’m not right, sir,” Coffman said. “Old Mad Jack’s got feet bigger than a plowhorse.”

As Starbuck marched into the ford, he looked at the General’s feet. They were indeed enormous. So were Jackson’s hands. But what was most extraordinary of all was why the General still held his left hand in midair like a child begging permission to leave a schoolroom. Starbuck was about to ask Coffman for an explanation when, astonishingly, the General stirred. He looked up from the water, and his gaze focused on Starbuck’s company. “Coffman!” he called in an abrupt, high-pitched voice. “Come here, boy.”

Coffman stumbled out of the ford and half ran to the General’s side. “Sir?”

The ragged-bearded Jackson frowned down from his saddle. “Do you remember me, Coffman?”

“Yes, sir, of course I do, sir.”

Jackson lowered his left hand very gently, as though he feared he might damage the arm if he moved it fast. “I was sorry you had to leave the Institute early, Coffman. It was after your plebe year, was it not?”

“Yes, sir. It was, sir.”

“Because your father died?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And your mother, Coffman? She’s well?”

“Indeed, sir. Yes, sir, thank you, sir.”

“Bereavement is a terrible affliction, Coffman,” the General observed, then slowly unbent his rigid posture to lean toward the slim, fair-haired Lieutenant, “especially for those who are not in a state of grace. Are you in a state of grace, Coffman?”

Coffman blushed, frowned, then managed to nod. “Yes, sir. I think I am, sir.”

Jackson straightened again into his poker-backed stance and, as slowly as he had lowered his left hand, raised it once more into midair. He lifted his eyes from Coffman to stare into the heat-hazed distance. “You will find it a very hard thing to meet your Maker if you are unsure of His grace,” the General said in a kindly voice, “so study your scriptures and recite your prayers, boy.”

“Yes, sir, I will, sir,” Coffman said. He stood awkward and uncertain, waiting for the General to speak further, but Jackson seemed in his trance once again, and so the Lieutenant turned and walked back to Starbuck’s side. The Legion marched on, and the Lieutenant remained silent as the road climbed between small pastures and straggling woods and beside modest farms. It was a good two miles before Coffman at last broke his silence. “He’s a great man,” the Lieutenant said, “isn’t he, sir? Isn’t he a great man?”

“Tom Fool?” Starbuck teased Coffman.

“A great man, sir,” Coffman chided Starbuck.

“If you say so,” Starbuck said, though all he knew about Jackson was that Old Mad Jack had a great reputation for marching, and that when Old Mad Jack went marching, men died. And they were marching now, marching north, and going north meant one thing only: Yankees ahead. Which meant there would be a battle soon, and a field of graves after the battle, and this time, if Pecker was right, Starbuck’s enemies would not just be in front of him but behind as well. Starbuck marched on. A fool going to battle.

The midday train stopped at Manassas Junction amidst a clash of cars, the hissing of steam, and the clangor of the locomotive’s bell. Sergeants’ voices rose over the mechanical din, urging troops out of the cars and onto the strip of dirt that lay between the rails and the warehouses. The soldiers jumped down, glad to be free of the cramped cars and excited to be in Virginia. Manassas Junction might not be the fighting front, but it was still a part of a rebel state, and so they peered about themselves as though the landscape was as wondrous and strange as the misty hills of mysterious Japan or far Cathay.

The arriving troops were mostly seventeen- and eighteen-year-old boys come from New Jersey and Wisconsin, from Maine and Illinois, from Rhode Island and Vermont. They were volunteers, newly uniformed and eager to join this latest assault on the Confederacy. They boasted of hanging Jeff Davis from an apple tree, and bragged of how they would march through Richmond and roust the rebels out of their nests like rats from a granary. They were young and indestructible, full of confidence, but also awed by the savagery of this strange destination.

For Manassas Junction was not an inviting place. It had been sacked once by Northern troops, destroyed again by retreating Confederates, then hastily rebuilt by Northern contractors, so that now there were acres of gaunt, raw-timbered warehouses standing between rail sidings and weed-filled meadows that were crammed with guns and limbers and caissons and portable forges and ambulances and wagons. More stores and weapons arrived every hour, for this was the supply depot that would fuel the summer campaign of 1862 that would end the rebellion and so restore a United States of America. The great spread of buildings was shadowed by an ever-present pall of greasy smoke that came from blacksmiths’ shops and locomotive repair sheds and the fireboxes of the locomotives that dragged in their goods wagons and passenger cars.