Полная версия:

1356

BERNARD CORNWELL

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2012

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 2012

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

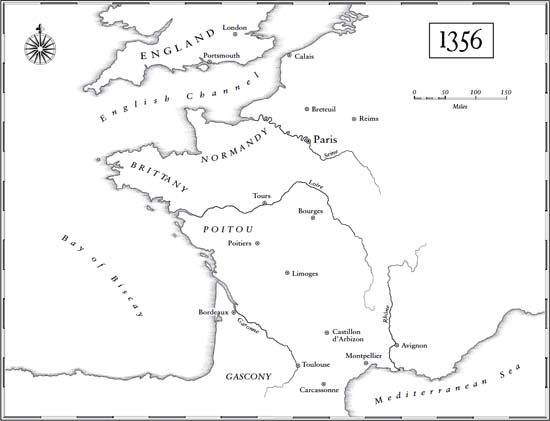

Maps © John Gilkes 2012

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Source ISBN: 9780007331840

Ebook Edition © September 2012 ISBN: 9780007331888

Version: 2017-05-05

FIRST EDITION

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

is for my grandson,

Oscar Cornwell,

with love.

‘The English are riding, no-one knows where.’

Warning sent in fourteenth-century France, quoted inA Fool and His Money by Ann Wroe

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Map

Prologue: CARCASSONNE

Part One: AVIGNON

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Part Two: MONTPELLIER

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Part Three: POITIERS

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Part Four: BATTLE

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

HISTORICAL NOTE

Two Chronicles of Poitiers

About the Author

Also by Bernard Cornwell

The Sharpe Series (in chronological order)

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

Carcassonne

He was late.

Now it was dark and he had no lantern, but the city’s flames gave a lurid glow that reached deep into the church and gave just enough light to show the stone slabs in the deep crypt where the man struck at the floor with an iron crow.

He was attacking a stone incised with a crest that showed a goblet wreathed by a buckled belt on which was written Calix Meus Inebrians. Sun rays carved into the granite gave the impression of light radiating from the cup. The carving and inscription were worn smooth by time, and the man had taken little notice of them, though he did notice the cries from the alleyways around the small church. It was a night of fire and suffering, so much screaming that it smothered the noise as he struck the stone flags at the edge of the slab to chip a small space into which he could thrust the long crow. He rammed the iron bar down, then froze as he heard laughter and footsteps in the church above. He shrank behind an archway just before two men came down into the crypt. They carried a flaming torch that lit the long, arched space and showed that there was no easy plunder in sight. The crypt’s altar was plain stone with nothing but a wooden cross for decoration, not even a candlestick, and one of the men said something in a strange language, the other laughed, and both climbed back to the nave where the flames from the streets lit the painted walls and the desecrated altars.

The man with the iron crow was cloaked and hooded in black. Beneath the heavy cloak he wore a white robe that was smeared with dirt, and the robe was girdled with a three-knotted cord. He was a Black Friar, a Dominican, though on this night that promised no protection from the army that ravaged Carcassonne. He was tall and strong, and before he had taken his vows he had been a man-at-arms. He had known how to thrust a lance, cut with a sword, or kill with an axe. He had been called Sire Ferdinand de Rodez, but now he was simply Fra Ferdinand. Once he had worn mail and plate, he had ridden in tournaments and slaughtered in battle, but for fifteen years he had been a friar and had prayed each day for his sins to be forgiven. He was old now, almost sixty, though still broad in the shoulders. He had walked to reach this city, but the rains had slowed his journey by flooding the rivers and making fords impassable and that was why he was late. Late and tired. He rammed the crow beneath the carved slab and heaved again, fearing that the iron would bend before the stone yielded, then suddenly there was a coarse grating sound and the granite lifted and then slid sideways to offer a small gap into the space beneath.

The space was dark because the devil’s flamelight from the burning city could not reach into the grave, and so the friar knelt by the dark hole and groped. He discovered wood and so he thrust the crow down again. One blow, two blows, and the wood splintered, and he prayed there was no lead coffin inside the timber casket. He thrust the crow a last time, then reached down and pulled pieces of splintered wood out of the hole.

There was no lead coffin. His fingers, reaching far down into the tomb, found cloth that crumbled when he touched it. Then he felt bones. His fingers explored a dry eye-hole, loose teeth, and discovered the curve of a rib. He lay down so he could stretch his arm deeper and he groped in the grave’s blackness and found something solid that was not bone. But it was not what he sought; it was the wrong shape. It was a crucifix. Voices were suddenly loud in the church above. A man laughed and a woman sobbed. The friar lay motionless, listening and praying. For a moment he despaired, thinking that the object he sought was not in the tomb, but then he reached as far as he could and his fingers touched something wrapped in a fine cloth that did not crumble. He fumbled in the dark, caught hold of the cloth, and tugged. Some object was wrapped inside the fine cloth, something heavy, and he inched it towards him, then caught proper hold of it and drew the object free of the bone hands that had been clutching it. He pulled the thing from the tomb and stood. He did not need to unwrap it. He knew he had found la Malice, and in thanks he turned to the simple altar at the crypt’s eastern end and made the sign of the cross. ‘Thank you, Lord,’ he said in a murmur, ‘and thank you, Saint Peter, and thank you Saint Junien. Now keep me safe.’

The friar would need heavenly help to be safe. For a moment he considered hiding in the crypt till the invading army left Carcassonne, but that might take days and, besides, once the soldiers had plundered everything easy they would open the crypt’s tombs to search for rings, crucifixes, or anything else that might fetch a coin. The crypt had sheltered la Malice for a century and a half, but the friar knew it would offer him no safety beyond a few hours.

Fra Ferdinand abandoned the crow and climbed the stairs. La Malice was as long as his arm and surprisingly heavy. She had been equipped with a handle once, but only the thin metal tang remained and he held her by that crude grip. She was still wrapped in what he thought was silk.

The church nave was lit by the houses that burned in the small square outside. There were three men inside the church, and one called a challenge to the dark-cloaked figure who appeared from the crypt steps. The three were archers, their long bow staves were propped against the altar, but despite the challenge they were not really interested in the stranger, only in the woman they had spreadeagled on the altar steps. For a heartbeat Fra Ferdinand was tempted to rescue the woman, but then four or five new men came through a side door and whooped when they saw the naked body stretched on the steps. They had brought another girl with them, a girl who screamed and struggled, and the friar shuddered at the sound of her distress. He heard her clothes tearing, heard her wail, and he remembered all his own sins. He made the sign of the cross, ‘Forgive me, Christ Jesus,’ he whispered and, unable to help the girls, he stepped through the church door and into the small square outside. Flames were consuming thatched roofs that flared bright, spewing wild sparks into the night wind. Smoke writhed above the city. A soldier wearing the red cross of Saint George was being sick on the church steps and a dog ran to lap up the vomit. The friar turned towards the river, hoping to cross the bridge and climb to the Cité. He thought that Carcassonne’s double walls, towers and crenellations would protect him because he doubted that this rampaging army would have the patience to conduct a siege. They had captured the bourg, the commercial district that lay west of the river, but that had never been defensible. Most of the town’s businesses were in the bourg, the leather shops and silversmiths and armourers and poulterers and cloth merchants, yet only an earth wall had surrounded those riches, and the army had swarmed over that puny barrier like a flood. Carcassonne’s Cité, though, was a fortress, one of the greatest in France, a bastion ringed by vast stone turrets and towering walls. He would be safe there. He would find a place to hide la Malice and wait until he could return it to its owner.

He edged into a street that had not been fired. Men were breaking into houses, using hammers or axes to splinter doors. Most of the citizens had fled to the Cité, but a few foolish souls had remained, perhaps hoping to protect their properties. The army had arrived so swiftly that there had been no time to take every valuable across the bridge and up to the monstrous gates that protected the hilltop citadel. Two bodies lay in the central gutter. They wore the four lions of Armagnac, crossbowmen killed in the hopeless defence of the bourg.

Fra Ferdinand did not know the city. Now he tried to find a hidden way to the river, using shadowed alleys and narrow passages. God, he thought, was with him, for he met no enemies as he hurried eastwards, but then he came to a wider street, lit bright by flames, and he saw the long bridge, and beyond it, high on the hill, the fire-reflecting walls of the Cité. The stones of the wall were reddened by the fires blazing in the bourg. The walls of hell, the friar thought, and then a gust of the night wind swirled a great mask of smoke down to shroud his view of the walls, but not the bridge, and on the bridge, guarding its western end, were archers. English archers with their red-crossed tunics and their long deadly bows. Two horsemen, mailed and helmeted, were with the archers.

No way to cross, he thought. No way to reach the safety of the Cité. He crouched, thinking, then headed back into the alleys. He would go north.

He had to cross a major street lit by newly set fires. A chain, one of the many that had been strung across the roadway to hold up the invaders, lay in the gutter where a cat lapped at blood. Fra Ferdinand ran through the firelight, dodged into another alley, and kept running. God was still with him. The stars were obscured by smoke in which sparks flew. He crossed a square, was baulked by a dead-end alley, retraced his steps, and headed north again. A cow bellowed in a burning building, a dog ran across his path with something black and dripping in its teeth. He passed a tanner’s shop, jumping over the hides that were strewn on the cobbles, and there ahead was the risible earth bank that was the bourg’s only defence, and he climbed it, then heard a shout and glanced behind to see three men pursuing him.

‘Who are you?’ one shouted.

‘Stop!’ another bellowed.

The friar ignored them. He ran down the slope, heading towards the dark countryside that lay beyond the huddle of cottages built outside the earthen bank, as an arrow hissed past him, missing him by the grace of God and the width of a finger, and he twisted aside into a passage between two of the small houses. A steaming manure heap stank there. He ran past the dung and saw the passage ended in a wall, and turned back to see the three men barring his path. They were grinning.

‘What have you got?’ one of them asked.

‘Je suis Gascon,’ Fra Ferdinand said. He knew the city’s invaders were both Gascons and English, and he spoke no English. ‘Je suis Gascon!’ he said again, walking towards them.

‘He’s a Black Friar,’ one of the men said.

‘But why did the goddamned bastard run?’ another of the Englishmen asked. ‘Got something to hide, have you?’

‘Give it here,’ the third man said, holding out his hand. He was the only one with a strung bow; the other two had their bows slung on their backs and were holding swords. ‘Come on, arseface, give it me.’ The man reached for la Malice.

The three men were half the friar’s age, and, because they were archers, probably twice as strong, but Fra Ferdinand had been a great man-at-arms and the skills of the sword had never deserted him. And he was angry. Angry because of the suffering he had seen and the cruelties he had heard, and that anger made him savage. ‘In the name of God,’ he said, and whipped la Malice upwards. She was still wrapped in silk, but her blade cut hard into the archer’s outstretched wrist, severing the tendons and breaking bone. Fra Ferdinand was holding her by the tang, which offered a perilous grip, but she seemed alive to him. The wounded man recoiled, bleeding, as his companions roared with anger and stabbed their blades forward, and the friar parried both with one cut and lunged forward, and la Malice, though she had been in a tomb for over a hundred and fifty years, proved as sharp as a newly honed blade and her fore-edge skewered through the padded haubergeon of the nearest man and opened his ribs and ripped into a lung, and before the man even knew he had been wounded Fra Ferdinand had swept the blade sideways to take the third man’s eyes and blood brightened the alleyway and all three men were retreating now, but the Black Friar gave them no chance to escape. The blinded man tripped backwards onto the manure pile, his companion hacked his blade in desperation, and la Malice met it and the English sword broke in two and the friar flicked the silk-wrapped blade to cut that man’s gullet and felt the blood splash on his face. So warm, he thought, and God forgive me. A bird shrieked in the darkness, and the flames roared up from the bourg.

He killed all three archers, then used the silk wrapping to clean la Malice’s blade. He thought of saying a brief prayer for the men he had just killed, then decided he did not want to share heaven with such brutes. Instead he kissed la Malice, then searched the three bodies and found some coins, a lump of cheese, four bowstrings, and a knife.

The city of Carcassonne burned and filled the winter night with smoke.

And the Black Friar walked north. He was going home, home to the tower.

He carried la Malice and the fate of Christendom.

And he vanished into darkness.

The men came to the tower four days after Carcassonne had been sacked.

There were sixteen of them, all cloaked in fine, thick wool and all mounted on good horses. Fifteen of the men wore mail and had swords at their waists, while the remaining rider was a priest who carried a hooded hawk on his wrist.

The wind came harsh down the mountain pass, ruffling the hawk’s feathers, rattling the pines and whipping the smoke from the small cottages of the village that lay beneath the tower. It was cold. This part of France rarely saw snow, but the priest, glancing from beneath the black hood of his cloak, thought there might be flakes in the wind.

There were ruined walls about the tower, evidence that this had once been a stronghold, but all that was left of the old castle was the tower itself and a low thatched building where perhaps servants lived. Chickens scratched in the dust, a tethered goat stared at the horses, while a cat ignored the newcomers. What had once been a fine small fortress, guarding the road into the mountains, was now a farmstead, though the priest noticed that the tower was still in good repair, and the small village in the hollow beneath the old fortress looked prosperous enough.

A man scurried from the thatched hut and bowed low to the horsemen. He did not bow because he recognised them, but because men with swords command respect. ‘Lords?’ the man asked anxiously.

‘Shelter the horses,’ the priest demanded.

‘Walk them first,’ one of the mailed men added, ‘walk them, rub them down, don’t let them eat too much.’

‘Lord,’ the man said, bowing again.

‘This is Mouthoumet?’ the priest asked as he dismounted.

‘Yes, father.’

‘And you serve the Sire of Mouthoumet?’ the priest asked.

‘The Count of Mouthoumet, yes, lord.’

‘He lives?’

‘Praise be to God, father, he lives.’

‘Praise be to God indeed,’ the priest said carelessly, then strode to the tower door, which stood at the top of a brief flight of stone steps. He called for two of the mailed men to accompany him and ordered the rest to wait in the yard, then he pushed open the door to find himself in a wide, round room used to store firewood. Hams and bunches of herbs hung from the beams. A stair led around one half of the wall, and the priest, not bothering to announce himself or wait for an attendant to greet him, took the stairs to the upper floor where a hearth was built into the wall. A fire burned there, though much of its smoke swirled about the circular room, driven back through the vent by the cold wind. The ancient wooden floorboards were covered in threadbare rugs; there were two wooden chests on which candles burned because, though it was daylight outside, the room’s two windows had been hung with blankets to block the draughts. There was a table on which lay two books, some parchments, an ink bottle, a sheaf of quills, a knife, and an old rusted breastplate that served as a bowl for three wrinkled apples. A chair stood by the table while the Count of Mouthoumet, lord of this lonely tower, lay in a bed close to the smouldering fire. A grey-haired priest sat beside him, and two elderly women knelt at the bed’s foot. ‘Leave,’ the newly arrived priest ordered the three. The two mailed men came up the stairs behind him and seemed to fill the room with their baleful presence.

‘Who are you?’ the grey-haired priest asked nervously.

‘I said leave, so leave.’

‘He’s dying!’

‘Go!’

The old priest, a scapular about his neck, abandoned the sacraments and followed the two women down the stairs. The dying man watched the newcomers, but said nothing. His hair was long and white, his beard untrimmed, and his eyes sunken. He saw the priest place the hawk on the table, where the bird’s talons made scratching noises. ‘She is une calade,’ the priest explained.

‘Une calade?’ the count asked, his voice very low. He stared at the bird’s slate-grey feathers and pale streaked breast. ‘It is too late for a calade.’

‘You must have faith,’ the priest said.

‘I have lived over eighty years,’ the count said, ‘and I have more faith than I have time.’

‘You have enough time for this,’ the priest said grimly. The two mailed men stood at the stairhead and said nothing. The calade made a mewing noise, but when the priest snapped his fingers the hooded bird went still and quiet. ‘You were given the sacrament?’ the priest asked.

‘Father Jacques was about to give it to me,’ the dying man said.

‘I will do it,’ the priest said.

‘Who are you?’

‘I come from Avignon.’

‘From the Pope?’

‘Who else?’ the priest asked. He walked about the room, examining it, and the old man watched him. He saw a tall, hard-faced man, his priest’s robes finely tailored. When the visitor lifted a hand to touch the crucifix hanging on the wall his sleeve fell open to reveal a lining of red silk. The old man knew this kind of priest, hard and ambitious, rich and clever, the kind who did not minister to the poor, but climbed the ladder of clerical power into the company of the rich and privileged. The priest turned and gazed at the old man with hard green eyes. ‘Tell me,’ he said, ‘where is la Malice?’

The old man hesitated a second too long. ‘La Malice?’

‘Tell me where she is,’ the priest demanded and, when the old man said nothing, added, ‘I come from the Holy Father. I order you to tell me.’

‘I don’t know the answer,’ the old man whispered, ‘so how can I tell you?’

A log crackled in the fire, spewing sparks. ‘The Black Friars,’ the priest said, ‘have been spreading heresies.’

‘God forbid,’ the old man said.

‘You have heard them?’

The count shook his head. ‘I hear little these days, father.’

The priest reached into a pouch that hung at his waist and brought out a scrap of parchment. ‘The Seven Dark Lords possessed it,’ he read aloud, ‘and they are cursed. He who must rule us will find it, and he shall be blessed.’

‘Is that heresy?’ the count asked.

‘It is a verse the Black Friars are telling all over France. All over Europe! There is only one man to rule us, and that is the Holy Father. If la Malice exists then it is your Christian duty to tell me what you know. She must be given to the church! A man who thinks otherwise is a heretic.’

‘I am no heretic,’ the old man said.

‘Your father was a Dark Lord.’

The count shuddered. ‘The sins of the father are not mine.’

‘And the Dark Lords possessed la Malice.’

‘They say many things about the Dark Lords,’ the count said.

‘They protected the treasures of the Cathar heretics,’ the priest said, ‘and when, by the grace of God, those heretics were burned from the land, the Dark Lords took their treasures and hid them.’

‘I have heard that.’ The count’s voice was scarce above a whisper.

The priest reached out and stroked the hawk’s back. ‘La Malice,’ he said, ‘has been lost these many years, but the Black Friars say she can be found. And she must be found! She is a treasure of the church, a thing of power! A weapon to bring Christ’s kingdom to earth, and you conceal it!’

‘I do not!’ the old man protested.

The priest sat on the bed and leaned close to the count. ‘Where is la Malice?’ he asked.