Полная версия:

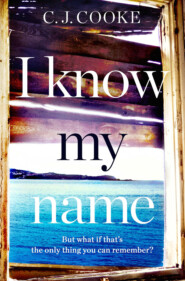

I Know My Name: An addictive thriller with a chilling twist

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © C.J. Cooke 2017

Cover design by Heike Schüssler © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover Photograph © Josephine Pugh / Arcangel Images

C.J. Cooke asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008237530

Ebook Edition © June 2017 ISBN: 9780008237547

Version: 2017-04-24

Dedication

For Summer

Little lover of horses

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

The Girl on the Beach

17 March 2015

17 March 2015

17 March 2015

18 March 2015

18 March 2015

18 March 2015

19 March 2015

18 March 2015

20 March 2015

18 March 2015

11 April 1983

23 March 2015

23 March 2015

24 March 2015

24 March 2015

24 March 2015

25 March 2015

21 January 1986

28 March 2015

27 March 2015

29 March 2015

29 March 2015

Red Wool

14 November 1988

31 March 2015

31 March 2015

1 April 2015

24 April 1990

2 April 2015

2 April 2015

31 March 2015

2 April 2015

1 April 2015

2 April 2015

1 April 2015

2 April 2015

2 April 2015

2 April 2015

2 April 2015

2 April 2015

2 April 2015

The Light That Moves Inward and Outward

3 April 2015

3 May 2015

25 June 2015

Three Years Later, 17 October 2018

Afterword

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

17 March 2015

Komméno Island, 8.4 miles northwest of Crete

I’m woken by the sounds of feet shuffling by my ears and voices knitting together in panic.

Is she dead? What should we do? Joe! You know CPR, don’t you?

A weight presses down against my lips. The bitter smell of cigarettes rushes up to my nostrils. Hot breath inflates my cheeks. A push downward on my chest. Another. I jerk upright, vomiting what feels like gallons of disgusting salty liquid. Someone rubs my back and says, Take it easy, sweetie. That’s it.

I twist to one side and lower my forehead to the ground, coughing, choking. My hair is wet, my clothes are soaking and I’m shaking with cold. Someone helps me to my feet and pulls my right arm limply across a broad set of shoulders. A yellow splodge on the floor comes into focus: it’s a life jacket. Mine? The man holding me upright lowers me gently into a chair. I hear their voices as they observe me, instructing each other on how to care for me.

Is that blood in her hair?

Joe, have a look. Has the bleeding stopped?

It looks quite deep, but I think it’s stopped. I’ve got some antiseptic swabs upstairs.

My head starts to throb, a dull pain towards the right. A cup of coffee materialises on the table in front of me. The smell winds upwards and sharpens my vision, bringing the people in the room into view. There’s a man nearby, panting from effort. Another man with black square glasses. Two others, both women. One of them leans over me and says, You OK, hun? I nod, dumbly. She comes into focus. Kind eyes. Well, Joe, she says. Looks like you saved her life.

I don’t recognise any of these people. I don’t know where I am. Whitewashed stone walls and a pretty stone floor. A kitchen, I think. Copper pots and pans hang from ceiling hooks, an old-fashioned black range oven visible at my right. I feel as though all energy has been sucked out of me, but the woman who gave me coffee urges me to keep awake. We need to check you over, sweetie. There’s an American lilt in her voice. I don’t think I noticed that before. She says, You’ve been unconscious for a while.

The younger man with black glasses tells me he’s going to check out my head. He steps behind me and all of a sudden I feel something cold and stinging on my scalp. I gasp in pain. Someone squeezes my hand and tells me he’s cleaning the wound. He looks over a spot above my eyebrow and cleans it, too, though he tells me it’s only a scratch.

The man who hoisted me into the chair sits opposite. Bald, heavy-set. Mid to late forties. Cockney. He takes a cigarette from a packet, plops it into his mouth and lights it.

You come from the main island?

Main island? I say, my voice a croak.

From there to here on her own? the younger man says. There’s no way she’d have managed in that storm.

I think that’s the point, Joe, the bald guy says. She’s lucky her boat didn’t capsize before it hit the beach.

The woman who served me coffee brings a chair and sits at my right.

I’m Sariah, she says. Good to meet you. Then, to the others in the room, Well, she’s awake now. Why don’t we stop being rude and introduce ourselves?

The guy with glasses gives a wave.

Joe.

George, says the bald man. I’m the one who found you.

Silence. Joe turns to the thin woman at his right, expectant. She seems nervous. Hazel, she says, her voice no more than an exhalation.

You got a name? George asks me.

My mind is blank. I look over the faces of the others, fitting their faces to these names, and yet my own won’t come. I feel physically weak and battered, but I’m lucid and able to think clearly.

It’s OK, sweetie, Sariah is saying, rubbing my shoulders. You’ve had a rough time. Take it easy. It’ll come.

You holidaying on the main island? George asks again.

My head feels like someone is pounding it with a hammer. I’m sorry … what is the main island?

Crete, Sariah answers. Whereabouts were you staying?

You staying with family? A group of girlfriends? the guy with glasses asks. Hey, she might have come from one of the other islands. Antikythera?

I don’t think so, offers the tiny woman with red curly hair – Hazel – in a low voice. The currents between here and Antikythera are worse than travelling to Crete. And Antikythera is further.

I’m sorry, I say. Did someone say I’m in Crete?

See? George says.

No, no, I try to say, but Joe cuts me off.

She asked if she’s in Crete, Joe answers. This is Komméno, not Crete.

Well, we’ll need to let whoever you’ve left behind know that you’re still in one piece, George says. You got a number I can ring?

He pulls a small black phone from a pocket and extends an antenna from the top. Crete. Was I staying there?

I can’t remember, I say finally. Sorry, I don’t know.

The kind woman, Sariah, is holding my hand. We’ll call the police on Crete the second we get a signal on the satellite phone. Don’t worry, sweetie.

The big guy – George – is still watching me, his eyes narrowed. Where are you from, then?

I’m light-headed and nauseous, but I think I should know this. It’s ridiculous, but I can’t even call it to mind. Why can’t I remember it? I try to think of faces of my family, people I love – but there’s a complete blankness in whatever part of my brain holds that information.

George is leaning on one hand, taking slow, thoughtful drags from a fresh cigarette, studying me. The others are halfway through cups of tea. I have no recollection of anyone putting cups out or boiling a kettle. Time lurches and stalls. I rise from my chair and almost fall over. My legs are jelly. Sariah moves to hold me up.

Easy now.

The large window at the other side of the kitchen frames a round moon in a purple sky, its glow bleaching fields and hills. A burst of light crackles across the ocean, lighting up the room. A few moments later thunder pounds the roof, rattling all the pots and pans. I am disoriented and weak. I begin to shake again, but this time it’s from shock.

Sariah wraps an arm around me. We’re going to move you into the other room, OK? Deep breaths.

But before we have a chance to move, I hear a deep voice say, Maybe she’s a refugee.

Sariah hisses, George!

He gives a loud bellow of laughter. It makes me jump.

I’m joking, aren’t I?

Pressure builds and builds in my head until I’m gasping for air and clawing at my throat. The two women lean forward and tell me to breathe, and I’m trying. They ask me to tell them what’s wrong but I can’t speak. Someone says,

We need to think about getting her to a hospital.

17 March 2015

George Street, Edinburgh

Lochlan: I’m having afternoon tea with a client at The Dome when my phone rings. It’s an important meeting – Mr Coyle is interested in setting up a venture capital fund to invest in some new technological companies – and so I pull it out of my pocket and hit ‘cancel’.

‘Sorry about that.’

Mr Coyle arches an eyebrow. ‘Your wife?’

It was, actually. Right before I hit ‘cancel’ I saw her name appear on the screen.

‘No, no. Anyway, what were we saying?’

‘Google glass?’

I pour us both some red. ‘Ah, yes. This company’s creating something similar, only better. It integrates seamlessly with new social media platforms and user trials have rated it at five stars. The first product is scheduled to retail for around five hundred pounds in September.’

My phone rings again. This time Mr Coyle gives a noise of irritation. ‘ELOÏSE’ appears in white letters on the screen. I make to hit ‘cancel’ again, but Mr Coyle gives a shooing gesture with his hand and says, ‘Answer it. Tell her we’re busy.’

I stand up and walk to the nearest window.

‘El, what is it? I’m in a meeting …’

‘Lochlan? Is that you, dear?’

The woman at the other end of the line is not my wife. She continues talking, and it takes a few moments for me to place the voice.

‘Mrs Shahjalal?’

It’s the Yorkshirewoman who lives opposite us.

‘… and I thought I’d best check. So when I opened the door I was surprised to see – are you still there?’

From the corner of my eye I see Mr Coyle hailing a waitress.

‘Mrs Shahjalal, is everything all right? Where’s Eloïse?’

A long pause. ‘That’s what I’m telling you, dear. I don’t know.’

‘What do you mean, you don’t know?’

‘It’s like I said: the man from the UPS van brought the parcel over to me and asked if I’d take it as nobody was in. And I thought that was strange, because I was sure I’d seen little Max’s face at the window only a moment before. So I took the parcel, and then an hour or so later I saw Max again, and I thought I’d best go over and see if everything was all right. Max was able to stand on a chair and let me in.’

I’m struggling to put this all together in my mind. Mr Coyle is rising from his chair, putting on his jacket. I turn and raise a hand to let him know I’ll be just a second, but he grimaces.

‘OK, so Max let you in to our house. What happened when you went inside?’

‘Well, Eloïse still isn’t here. I’ve been here since three o’clock and the little one’s mad for a feed. I found Eloïse’s mobile phone on the coffee table and pressed a button, and luckily enough it dialled your number.’

The rustling and mewling noises in the background grow louder, and I realise Mrs Shahjalal must be holding Cressida, my daughter. She’s twelve weeks old. Eloïse is still breastfeeding her.

‘So … Eloïse isn’t in the house. She’s not there at all?’ It’s a stupid thing to say, but I can’t quite fathom it. Where else would she be?

Mr Coyle glowers from the table. He straightens his tie before turning to walk out, and I lower the phone and call after him.

‘Mr Coyle!’

He doesn’t acknowledge me.

‘I’ll send the fact sheet by email!’

Mrs Shahjalal is still talking. ‘It’s very odd, Lochlan. Max is dreadfully upset and doesn’t seem to know where she’s gone. I don’t know what to do.’

I walk back to the table and gather up my briefcase. The brass clock on the chimneybreast reads quarter past four. I could catch the four thirty to London if I manage to get a taxi on time, but it’s a four-and-a-half-hour train ride from here and then another cab ride from King’s Cross to Twickenham. I’ll not be home until after ten.

‘I’m heading back right now,’ I tell Mrs Shahjalal.

‘Are you in the city, dear?’

‘I’m in Edinburgh.’

‘Edinburgh? Scotland?’

Outside, the street is busy with traffic and people. I’m agitated, trying to think fast, and almost get knocked over by a double-decker bus driving close to the kerb. I jump back, gasping at the narrow escape. A group of school kids on a school trip meander across the pavement in single file. I wave at a black taxi and manage to get him to stop.

‘To Waverley, please.’

I ask Mrs Shahjalal if she can stay with Max and Cressida until I get back. To my relief she says she will, though I can barely hear her now over Cressida’s screams.

‘She needs to be fed, Mrs Shahjalal.’

‘Well, I know that, dear, but my days of being able to nurse a baby are over.’

‘If you go into the fridge, there might be some breast milk in a plastic container on the top shelf. It’ll be labelled. I think Eloïse keeps baby bottles in one of the cupboards near the toaster. Make sure you put the bottle into the steriliser in the microwave for four minutes before you use it. Make sure there’s water in the bottom.’

‘Sterilise the breast milk?’

I can hear Max in the background now, shouting, ‘Is that Daddy? Daddy, is that you?’ I ask Mrs Shahjalal to put him on.

‘Max, Maxie boy?’

‘Hi, Daddy. Can I have some chocolate, please?’

‘I’ll buy you as much chocolate as you can eat if you tell me where Mummy is.’

‘As much chocolate as I can eat? All of it?’

‘Where is Mummy, Max?’

‘Can I have a Kinder egg, please?’

‘Did Mummy go out this morning? Did someone come to the house?’

‘I think she went to the Natural History Museum, Daddy, ’cos she likes the dinosaurs there and the big one that’s very long is called Dippy, he’s called Dippy ’cos he’s a Diplodocus, Daddy.’

I’m getting nowhere. I ask him to put me back on to Mrs Shahjalal, who is still wondering how she is to sterilise the breast milk, and all the while Cressida is drilling holes in my head by screaming down the phone.

Finally, I’m on the train, posting on Facebook.

I don’t usually do this but … anyone know where Eloïse is? She doesn’t seem to be at home …

Night falls like a black sheath. The taxi pulls into Potter’s Lane. We live in a charming Edwardian semi in the quiet suburb of Twickenham, close to all the nice parks and the part of the river inhabited by swans, frogs and ducks, and close enough to London for Saturday-afternoon visits to the National History Museum and Kew Gardens. A few lights are on in the houses near us, but our neighbours are either retired or hard-working professionals, and so nights are placid round here.

I pay the driver and jump out on to the pavement. Eloïse’s white Qashquai is parked in the driveway in front of my Mercedes, and my hearts leaps. I’ve been on and off the phone to Mrs Shahjalal during the train ride from Edinburgh, checking in on the kids and trying to work out what the hell to do about the situation. Mrs Shahjalal is very old and forgetful. More than once El has climbed through the window to open the front door because she locked her keys inside. In all likelihood this is a big mistake; I’ve lost a client while El’s been upstairs having a shower or something. I ran out of battery on my phone some time ago and all the power points on the train were broken. Mrs Shahjalal hasn’t been able to contact me. But the Qashquai’s here. Eloïse must have arrived back already.

I turn my key in the door and step inside to quietness and darkness.

‘El?’

I head into the playroom and see the figure of old Mrs Shahjalal sitting on the edge of the sofa, rocking the Moses basket where Cressida is lying, arms raised at right angles by her tiny head.

‘Hi,’ I whisper. ‘Where is she?’

Mrs Shahjalal shakes her head.

‘But … she’s here,’ I say. ‘Her car is outside. Where is she?’

‘She isn’t here.’

‘But—’

Mrs Shahjalal raises a finger to her lips and looks down at Cressida in a manner that suggests it has taken a long time to settle her to sleep. Cressida gives a little shuddered breath, the kind she gives after a long paroxysm of wailing.

‘Max is upstairs, in his bed,’ Mrs Shahjalal says in a low voice.

‘But what about El’s car? The white one in the driveway?’

‘It’s been here all the time. She didn’t take it.’

I race upstairs and check the bedrooms, the bathrooms, the attic, then switch on all the lights downstairs and sift the rooms for my wife. When that proves fruitless I head out into the garden and stare into the darkness. In that moment a daunting impossibility yawns wide. I barely know Mrs Shahjalal, save a few neighbourly waves across the street, and now she’s in my living room, gently rocking my daughter and telling me that my wife has vanished into thin air.

I take out my phone and begin to dial.

17 March 2015

Komméno Island, Greece

Somehow I find myself in a rocking chair with a thick orange blanket around me, next to a crackling fire. My right sleeve is rolled up and someone’s tied a belt tight around my bicep. The tall skinny bloke with glasses, Joe, is standing next to me with a cold instrument pressed to my wrist. The room smells funny – like seaweed. Or maybe that’s me.

‘Only a couple more seconds,’ he says.

‘What are you doing?’ I say, though it comes out as a strangled whine. The inside of my mouth feels like sandpaper.

‘Checking your blood pressure.’

There’s a heated discussion going on amongst the others in the room and I sense it’s about me. I still feel queasy and limp.

Eventually he removes the belt from my arm. ‘Hmmm. Your blood pressure is a bit low for my liking. How about the tightness in your chest?’

I tell him that it seems OK but that I’m weak as dishwater. He reaches forward and gently presses his thumbs on my cheeks to inspect my eyes.

‘You’re in shock. Little wonder, given that you rowed across the Aegean in a full-blown storm. Let’s get your feet raised up. And some more water.’

The woman – Sariah – lifts my feet and supports them on a stack of cushions.

‘How’s your head?’ she asks.

‘Sore,’ I say weakly.

‘You don’t feel like you’re going to pass out again?’ Joe asks, and I give a small shake of my head. It’s enough to make the pain ratchet up to an agony that leaves me breathless.

‘It’s after midnight, so getting you to a hospital has proved a little tricky,’ Sariah says, folding her arms. I notice she has a different accent than the others. American, or maybe Canadian. ‘There’s no hospital or doctors anywhere here,’ she says. ‘George has contacted the police in Heraklion and Chania.’

‘Did anyone report me as missing?’

‘I’m afraid not.’

She must see how this unnerves me because she lowers on her haunches and rubs my hand, as though I’m a child. ‘Hey, don’t worry,’ she says. ‘We’ll call again first thing in the morning.’

Nothing about this place feels familiar. It feels like I’m seeing everything here for the first time.

‘Do I live here? Do I know any of you?’ I ask her.

‘We saved you,’ George says flatly. I can’t see him, but sense his presence behind me.

‘There was a storm,’ Joe adds, though something in his voice sounds uncertain, hesitant. ‘Big sandstorm coming across from Africa, no doubt. George and I went out to check that our boat hadn’t come loose from its moorings. And then we saw you.’