Полная версия:

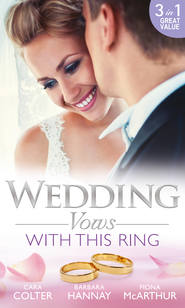

Wedding Vows: With This Ring: Rescued in a Wedding Dress / Bridesmaid Says, 'I Do!' / The Doctor's Surprise Bride

Unexpected weddings!

CARA COLTER

BARBARA HANNAY

FIONA MCARTHUR

Wedding

Vows With This Ring

Rescued in a Wedding Dress

Cara Colter

Bridesmaid Says, ‘I Do!’

Barbara Hannay

The Doctor’s Surprise Bride

Fiona McArthur

www.millsandboon.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Rescued in a Wedding Dress

About the Author

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Epilogue

Bridesmaid Says, ‘I Do!’

About the Author

Dedication

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

The Doctor’s Surprise Bride

About the Author

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

Copyright

Rescued in a Wedding Dress

Cara Colter

CARA COLTER lives in British Columbia with her partner, Rob, and eleven horses. She has three grown children and a grandson. She is a recent recipient of an RT Book Reviews Career Achievement Award in the Love and Laughter category. Cara loves to hear from readers and you can contact her or learn more about her through her website: www.cara-colter.com.

Chapter One

MOLLY MICHAELS stared at the contents of the large rectangular box that had been set haphazardly on top of the clutter on her desk. The box contained a wedding gown.

Over the weekend donations that were intended for one of the three New York City secondhand clothing shops that were owned and operated by Second Chances Charity Inc—and that provided the funding for their community programs—often ended up here, stacked outside the doorstep of their main office.

It did seem like a cruel irony, though, that this donation would end up on her desk.

“Sworn off love,” Molly told herself, firmly, and shut the box. “Allergic to amour. Lessons learned. Doors closed.”

She turned and hung up her coat in the closet of her tiny office, then returned to her desk. She snuck the box lid open, just a crack, then opened it just a little more. The dress was a confection. It looked like it had been spun out of dreams and silk.

“Pained by passion,” Molly reminded herself, but even as she did, her hand stole into the box, and her fingers touched the delicate delight of the gloriously rich fabric.

What would it hurt to look? It could even be a good exercise for her. Her relationship with Chuck, her broken engagement, was six months in the past. The dress was probably ridiculous. Looking at it, and feeling nothing, better yet judging it, would be a good test of the new her.

Molly Michaels was one hundred percent career woman now, absolutely dedicated to her work here as the project manager at Second Chances. It was her job to select, implement and maintain the programs the charity funded that helped people in some of New York’s most challenged neighborhoods.

“Love my career. Totally satisfied,” she muttered. “Completely fulfilled!”

She slipped the pure white dress out of the box, felt the sensuous slide of the fabric across her palms as she shook it out.

The dress was ridiculous. And the total embodiment of romance. Ethereal as a puff of smoke, soft as a whisper, the layers and layers of ruffles glittered with hundreds of hand-sewn pearls and tiny silk flowers. The designer label attested to the fact that someone had spent a fortune on it.

And the fact it had shown up here was a reminder that all those romantic dreams had a treacherous tendency to go sideways. Who sent their dress, their most poignant reminder of their special day, to a charity that specialized in secondhand sales, if things had gone well?

So, it wasn’t just her who had been burned by love. Au contraire! It was the way of the world.

Still, despite her efforts to talk sense to herself, there was no denying the little twist of wistfulness in her tummy as Molly looked at the dress, felt all a dress like that could stand for. Love. Souls joined. Laughter shared. Long conversations. Lonely no more.

Molly was disappointed in herself for entertaining the hopelessly naive thoughts, even briefly. She wanted to kill that renegade longing that stirred in her. The logical way to do that would be to put the dress back in the box, and have the receptionist, Tish, send it off to the best of Second Chances stores, Wow and Then, on the Upper West Side. That store specialized in high-end gently used fashions. Everything with a designer label in it ended up there.

But, sadly, Molly had never been logical. Sadly, she had not missed the fact the dress was exactly her size.

On impulse, she decided the best way to face her shattered dreams head-on would be to put on the dress. She would face the bride she was never going to be in the mirror. She would regain her power over those ever so foolish and hopelessly old-fashioned dreams of ever after.

How could she, of all people, believe such nonsense? Why was it that the constant squabbling of her parents, the eventual dissolution of her family, her mother remarrying often, had not prepared Molly for real life? No, rather than making her put aside her belief in love, her dreams of a family, her disappointment-filled childhood had instead made her yearn for those things.

That yearning had been drastic enough to make her ignore every warning sign Chuck had given her. And there had been plenty of them! Not at first, of course. At first, it had been all delight and devotion. But then, Molly had caught her intended in increasingly frequent insults: little white lies, lateness, dates not kept.

She had forgiven him, allowing herself to believe that a loving heart overlooked the small slights, the inconsiderations, the occasional surliness, the lack of enthusiasm for the things she liked to do. She had managed to minimize the fact that the engagement ring had been embarrassingly tiny, and efforts to address setting a date had been rebuffed.

In other words, Molly had been so engrossed in her fantasy about love, had been so focused on a day and a dress just like this one, that she had excused and tolerated and dismissed behavior that, in retrospect, had been humiliatingly unacceptable.

Now she was anxious to prove to herself that a dress like this one had no power over her at all. None! Her days of being a hopeless dreamer, of being naive, of being romantic to the point of being pathetic, were over.

Over and done. Molly Michaels was a new woman, one who could put on a dress like this and scoff at the beliefs it represented. Round-faced babies, a bassinet beside the bed, seaside holidays, chasing children through the sand, cuddling around a roaring fire with him, the dream man, beside you singing songs and toasting marshmallows.

“Dream man is right,” she scolded herself. “Because that’s where such a man exists. In dreams.”

The dress proved harder to get on than Molly could have imagined, which should have made her give it up. Instead, it made her more determined, which formed an unfortunate parallel to her past relationship.

The harder it had been with Chuck, the more she had tried to make it work.

That desperate-for-love woman was being left behind her, and putting on this dress was going to be one more step in helping her do it!

But first she got tangled in the sewn-in lining, and spent a few helpless moments lost in the voluminous sea of white fabric. When her head finally popped out the correct opening, her hair was caught hard in one of the pearls that encrusted the neckline. After she had got free of that, fate made one more last-ditch effort to get her to stop this nonsense. The back of the dress was not designed to be done up single-handedly.

Still, having come this far, with much determination and contortion, Molly somehow managed to get every single fastener closed, though it felt as if she had pulled the muscle in her left shoulder in the process.

Now she took a deep breath, girded her cynical loins, and turned slowly to look at herself in the full-length mirror hung on the back of her office door.

She closed her eyes. Goodbye, romantic fool. Then she took a deep breath and opened them.

Molly felt her attempt at cynicism dissolve with all the resistance of instant coffee granules meeting hot water. In fact everything dissolved: the clutter around her, the files that needed to be dealt with, the colorful sounds of the East Village awaking outside her open transom window, something called out harshly in Polish or Ukrainian, the sound of a delivery truck stopped nearby, a horn honking.

Molly stared at herself in the mirror. She had fully expected to see her romantic fantasy debunked. It would just be her, too tall, too skinny, redheaded and pale-faced Molly Michaels, in a fancy dress. Not changed by it. Certainly not completed by it.

Instead, a princess looked solemnly back at her. Her red hair, pulled out of its very professional upsweep by the entrapment inside the dress and the brief fray with the pearl, was stirred up, hissing with static, fiery and free. Her pale skin looked not washed out as she had thought it would against the sea of white but flawless, like porcelain. And her eyes shimmered green as Irish fields in springtime.

The cut of the dress had seemed virginal before she put it on. Now she could see the neckline was sinful and the rich fabric was designed to cling to every curve, making her look sensuous, red-hot and somehow ready.

“This is not the lesson I was hoping for,” she told herself, the stern tone doing nothing to help her drag her eyes away from the vision in the mirror. She ordered herself to take off the dress, in that same easily ignored stern tone. Instead, she did an experimental pose, and then another.

“I would have made a beautiful bride!” she cried mournfully.

Annoyed with herself, and with her weakness—eager to get away from all the feelings of loss for dreams not fulfilled that this dress was stirring up in her—she reached back to undo the fastener that held the zipper shut. It was stuck fast.

And much as she did not like what she had just discovered about herself—romantic notions apparently hopelessly engrained in her character—she could not bring herself to damage the dress in order to get it off.

Molly tried to pull it over her head without the benefit of the zipper, but it was too tight to slip off and when she lowered it again, all she had accomplished was her hair caught hard in the seed pearls that encrusted the neckline of the dress again.

It was as if the dress—and her romantic notions—were letting her know their hold on her was not going to be so easily dismissed!

Her phone rang; the two distinct beeps of Vivian Saint Pierre, known to one and all as Miss Viv, beloved founder of Second Chances. Miss Viv and Molly were always the first two into the office in the morning.

Instead of answering the phone, Molly headed out of her own office and down the hall to her boss’s office to be rescued.

From myself, she acknowledged wryly.

Miss Viv would look at this latest predicament Molly had gotten herself into, know instantly why Molly had been compelled to put on the dress and then as she was undoing the zip she would say something wise and comforting about Molly’s shattered romantic hopes.

Miss Viv had never liked Chuck Howard, Molly’s fiancé. When Molly had arrived at work that day six months ago with her ring finger empty, Miss Viv had nodded approvingly and said, “You’re well rid of that ne’er-do-well.”

And that was even before Molly had admitted that her bank account was as empty as her ring finger!

That was exactly the kind of pragmatic attention Molly needed when a dress like this one was trying to undo all the lessons she was determined to take from her broken engagement!

With any luck, by the end of the day her getting stuck in the dress would be nothing more than an office joke.

Determined to carry off the lighthearted laugh at herself, she burst through the door of Miss Viv’s office after a single knock, the wedding march humming across her lips.

But a look at Miss Viv, sitting behind her desk, stopped Molly in her tracks. The hum died midnote. Miss Viv did not look entertained by the theatrical entrance. She looked horrified.

And when her gaze slid away from where Molly stood in the doorway to where a chair was nearly hidden behind the open door, Molly’s breath caught and she slowly turned her head.

Despite the earliness of the hour, Miss Viv was not alone!

A man sat in the chair behind the door, the only available space for visitors in Miss Viv’s hopelessly disorganized office.

No, not just a man. The kind of man that every woman dreamed of walking down the aisle toward.

The man sitting in Miss Viv’s office was not just handsome, he was breathtaking. In a glance, Molly saw neat hair as rich as dark chocolate, firm lips, a strong chin with the faintest hint of a cleft, a nose saved from perfection—but made unreasonably more attractive—by the slight crook of an old break and a thin scar running across the bridge of it.

The aura of confidence, of success, was underscored by how exquisitely he was dressed. He was in a suit of coal-gray, obviously custom tailored. He had on an ivory shirt, a silk tie also in shades of gray. The ensemble would have been totally conservative had it not been for how it all matched the gray shades of his eyes. The cut of the clothes emphasized rather than hid the pure power of his build.

The power was underscored in the lines of his face.

And especially in the light in his eyes. The surprise that widened them did not cover the fact he radiated a kind of self-certainty, a cool confidence, that despite the veneer of civilization he wore so well, reminded Molly of a gunslinger.

In fact, that was the color of those eyes, exactly, gunmetal-gray, something in them watchful, waiting. She shivered with awareness. Despite the custom suit, the Berluti shoes, the Rolex that glinted at his wrist, he was the kind of man who sat with his back to the wall, always facing the door.

The man radiated power and the set of his shoulders telegraphed the fact that, unlike Chuck, this man was pure strength. The word excuse would not appear in his vocabulary.

No, Molly could tell by the fire in his eyes that if the ship was going down, or the building was on fire—if the town needed saving and he had just ridden in on his horse—he was the one you would follow, he was the one you would rely on to save you.

An aggravating conclusion since she was so newly committed to relying on herself, her career and her coworkers to save her from a disastrous life of unremitting loneliness. The little featherless budgie she had at home—the latest in a long list of loving strays that had populated her life—also helped.

The little swish of attraction she felt for the stranger made her current situation even more annoying. It didn’t matter how much he looked like the perfect person to cast in the center of a romantic fantasy! She had given up on such twaddle! She was well on her way to becoming one of those women perfectly comfortable sitting at an outdoor café, alone, sipping a fine glass of wine and reading a book. Not even slipping a look at the male passers-by!

Of course, this handsome devil appearing without warning in her boss’s office on a Monday morning was a test, just like the dress. It was a test of her commitment to the new and independent Molly Michaels, a test of her ability to separate her imaginings from reality.

Look at her deciding he was the one you would follow in a catastrophe when she knew absolutely nothing about him except that he had an exceedingly handsome face. Molly reminded herself, extra sternly, that all the catastrophes in her life had been of her own making. Besides, with the kind of image he portrayed—all easy self-assurance and leashed sexuality—probably more than one woman had built fantasies of hope and forever around him. He was of an age where if he wanted to be taken he would be. And if his ring finger—and the expression on his face as he looked at the dress—was any indication, he was not!

“Sorry,” Molly said to Miss Viv, “I thought you were alone.” She gave a quick, curt nod of acknowledgment to the stranger, making sure to strip any remaining hopeless dreamer from herself before she met his eyes.

“But, Molly, when I rang your office, I wanted you to come, and you must have wanted something?” Miss Viv asked her before she made her escape.

Usually imaginative, Molly drew a blank for explaining away her attire and she could think of not a single reason to be here except the truth.

“The zip is stuck, but I can manage. Really. Excuse me.” She was trying to slide back out the door when his eyes narrowed on her.

“Is your hair caught in the dress?”

His voice was at least as sensual as the silk where the dress caressed her naked skin.

Molly could feel her cheeks turning a shade of red that was probably going to put her hair to shame.

“A little,” she said proudly. “It’s nothing. Excuse me.” She tried to lift her chin, to prove how nothing it was, but her hair was caught hard enough that she could not, and she also could not prevent a little wince of pain as the movement caused the stuck hair to yank at her tender scalp.

“That looks painful,” he said quietly, getting to his feet with that casual grace one associated with athletes, the kind of ease of movement that disguised how swift they really were. But he was swift, because he was standing in front of her before she could gather her wits and make good her escape.

The smart thing to do would be to step back as he took that final step toward her. But she was astounded to find herself rooted to the spot, paralyzed, helpless to move away from him.

The world went very still. It seemed as if all the busy activity on the street outside ceased, the noises faded, the background and Miss Viv melted into a fuzzy kaleidoscope as the stranger leaned in close to her.

With the ease born of supreme confidence in himself—as if he performed this kind of rescue on a daily basis—he lifted the pressure of the dress up off her shoulder with one hand, and with the other, he carefully unwound her hair from the pearls they were caught in.

Given that outlaw remoteness in his eyes, he was unbelievably gentle, his fingers unhurried in her hair.

Molly’s awareness of him was nothing less than shocking, his nearness tingling along her skin, his touch melting parts of her that she had hoped were turned to ice permanently.

The moment took way too long. And not nearly long enough. His concentration was complete, the intensity of his steely-gray gaze as he dealt with her tangled hair, his unsettling nearness, the graze of his fingers along her neck, stealing her breath.

At least Molly didn’t feel as if she was breathing, but then she realized she must, indeed, be pulling air in and out, because she could smell him.

His scent was wonderful, bitingly masculine, good aftershave, expensive soap, freshly pressed linen.

Molly gazed helplessly into his face, unwillingly marveling at the chiseled perfection of his features, the intrigue of the faint crook in his nose, the white line of that scar, the brilliance of his eyes. He, however, was pure focus, as if the only task that mattered to him was freeing her hair from the remaining pearl that held it captive.

Apparently he was not marveling at the circumstances that had brought his hands to her hair and the soft place on her neck just below her ear, apparently he was not swamped by their scents mingling nor was he fighting a deep awareness that a move of a mere half inch would bring them together, full frontal contact, the swell of her breast pressing into the hard line of his chest…

The dress, suddenly freed, fell back onto her shoulder. He actually smiled then, the faintest quirk of a gorgeous mouth, and she felt herself floundering in the depths of stormy sea eyes, the chill gray suddenly illuminated by the sun.

“Did you say the zipper was stuck as well?” he asked.

Oh, God. Had she said that? She could not prolong this encounter! It was much more of a test of the new confidently-sitting-at-the-café-alone her than she was ready for!

But mutely, caught in a spell, she turned her back to him and stood stock-still, waiting. She shivered at the thought of a wedding night, what this moment meant, and at the same time that unwanted thought seeped warmly into her brain, he touched her.

She felt the slight brush of his hand, again, on delicate skin, this time at the back of her neck. Her senses were so intensely engaged that she heard the faint pop of the hook parting from the eye. She registered the feel of his hand, felt astounded by the hard, unyielding texture of his skin.

He looked like he was pure business, a banker maybe, a wealthy benefactor, but there was nothing soft about his hand that suggested a life behind a desk, his tools a phone and a computer. For some reason it occurred to her that hands like that belonged to people who handled ropes…range riders, mountain climbers. Pirates. Ah, yes, pirates with all that mysterious charm.

He dispensed with the hook at the top of the zipper in a split second, a man who had dispensed with such delicate items many times? And then he paused, apparently realizing the height of the zipper would make it nearly impossible for her to manage the rest by herself—she hoped he would not consider how much determination it had taken her to get it up in the first place—and then slid the zipper down a sensuous inch or two.

With that same altered sense of alertness Molly could feel cool air on that small area of her newly exposed naked back, and then, though she did not glance back, she could feel heat. His gaze? Her own jumbled thoughts?

Molly fought the chicken in her that just wanted to bolt out the open door. Instead, she turned and faced him.

“There you go,” he said mildly, rocking back on his heels. The heat must have come from her own badly rattled thoughts, because his eyes were cool, something veiled in their intriguing silver depths.