Полная версия:

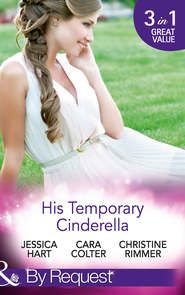

His Temporary Cinderella: Ordinary Girl in a Tiara / Kiss the Bridesmaid / A Bravo Homecoming

His Temporary Cinderella

Ordinary Girl in a Tiara

Jessica Hart

Kiss the Bridesmaid

Cara Colter

A Bravo Homecoming

Christine Rimmer

www.millsandboon.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Ordinary Girl in a Tiara

About the Author

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

Kiss the Bridesmaid

Dedication

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

A Bravo Homecoming

About the Author

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Copyright

Ordinary Girl in a Tiara

Jessica Hart

JESSICA HART was born in West Africa, and has suffered from itchy feet ever since—travelling and working around the world in a wide variety of interesting but very lowly jobs, all of which have provided inspiration on which to draw when it comes to the settings and plots of her stories. Now she lives a rather more settled existence in York, where she has been able to pursue her interest in history, although she still yearns sometimes for wider horizons. If you’d like to know more about Jessica, visit her website: www.jessicahart.co.uk.

CHAPTER ONE

To: caro.cartwright@u2.com

From: charlotte@palaisdemontvivennes.net

Subject: Internet dating

Dear Caro

What a shame about the deli folding. I know you loved that job. You must be really fed up, but your email about the personality test on that internet dating site really made me laugh—good to know you haven’t lost your sense of humour in spite of everything that skunk George did to you! All I can say is that compared to Grandmère’s matchmaking schemes, internet dating sounds the way to go. Perhaps we should swap lives??!

Lotty

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

To: charlotte@palaisdemontvivennes.net

From: caro.cartwright@u2.com

Subject: Swapping places

What a brilliant idea, Lotty! My life is a giddy whirl at the moment, what with temping at a local insurance company and trying to write profile for new dating site (personality test results too depressing on other one) but if you’d like to try it, you’re more than welcome! Of course, living your life would be tough for me—living in a palace, having (admittedly terrifying) grandmother introducing me to suitable princes and so on—but for you, Lotty, anything! Just let me know where and when and I’ll have a stab at being a princess for a change … ooh, that’s just given me an idea for my new profile. Who says fantasy isn’t good for you???

Yours unregally

Caro XXX

PRINCESS SEEKS FROG: Curvaceous, fun-loving brunette, 28, looking for that special guy for good times out and in.

‘What do you think?’ Caro read out her opening line to Stella, who was lying on the sofa and flicking through a copy of Glitz.

Stella looked up from the magazine, her expression dubious. ‘It doesn’t make sense. Princess seeks frog? What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘It means I’m looking for an ordinary guy, not a Prince Charming in disguise. I thought it was obvious,’ said Caro, disappointed.

‘No ordinary guy would ever work that out, I can tell you that much,’ said Stella. She went back to flicking. ‘You don’t want to be cryptic or clever. Men hate that.’

‘It’s all so difficult.’ Caro deleted the offending words on the screen, and chewed her bottom lip. ‘What about the curvaceous bit? I’m worried it might make me sound fat, but there’s not much point in meeting someone who’s looking for a slender goddess, is there? He’d just run away screaming the moment he laid eyes on me. Besides, I want to be honest.’

‘If you’re going to be honest, you’d better take out “fun-loving”,’ Stella offered. ‘It makes it sound as if you’re up for anything.’

‘That’s the whole point. I’m changing. Being sensible didn’t get me anywhere with George, so I’m going to be a good time girl from now on.’

She would be like Melanie, all giggles and low cut tops and flirty looks. Melanie, who had sashayed into George’s office and knocked Caro’s steady, sensible fiancé off his feet.

‘I can’t say what I’m really like or no one will want to go out with me,’ she added glumly.

‘Rubbish,’ said Stella. ‘Say you’re kind and generous and a brilliant cook—that would be honest.’

‘Guys don’t want kind, even if they say they do,’ Caro said bitterly, remembering George. ‘They want sexy and fun-loving.’

‘Hmm, well, if you want to be sexy, you’d better do something about your clothes,’ said Stella, lowering Glitz so that she could inspect her friend’s outfit with a critical eye. ‘I know you’re into the vintage look, but a crochet top?’

‘It’s an original from the Seventies.’

‘And it was vile then, too.’

Caro made a face at her. With the top she was wearing a tartan miniskirt from the nine-teen-sixties and bright red pumps. She was the first to admit that she couldn’t always carry off the vintage look successfully, but she had been pleased with this particular outfit until Stella had started shaking her head.

Still, there was no point in arguing. She went back to her profile. ‘OK, what about Keen cook seeks fellow foodie?’

‘You’ll just get some guy who wants to tie you to the stove and expect you to have his dinner ready the moment he comes through the door. You’ve already done that for George, and look where that got you.’ Stella caught the flash of pain on her friend’s face and her voice softened. ‘I know how miserable you’ve been, Caro, but honestly, you’re well out of it. George wasn’t the right man for you.’

‘I know.’ Caro caught herself sighing and squared her shoulders. ‘It’s OK, Stella. I’m fine now. I’m moving on, aren’t I?’

Pressing the backspace key with one finger, she deleted the last sentence. ‘It’s just so depressing having to sign up to these online dating sites. I don’t remember it being this hard before. It’s like in the five years I was with George, all the single men round here have disappeared into some kind of Bermuda Triangle!’

‘Yeah, it’s called marriage,’ said Stella. She picked up Glitz again and flicked through in search of the page she wanted. ‘I don’t know why you’re looking in Ellerby, though. Why don’t you get your friend Lotty to introduce you to some rich, glamorous men who eat in Michelin starred restaurants all the time?’

Caro laughed, remembering Lotty’s email. ‘I wish! But poor Lotty never gets within spitting distance of an interesting man either. You’d think, being a princess, she’d have a fantastically glamorous time, but her grandmother totally runs her life. Apparently she’s trying to fix Lotty up with someone “suitable” right now.’ Caro hooked her fingers in the air to emphasise the inverted commas. ‘I mean, who wants a man your grandmother approves of? I think I’d rather stick with internet dating!’

‘I wouldn’t mind if he was anything like the guy Lotty’s going out with at the moment,’ said Stella. ‘I saw a picture of them just a second ago. If he was her grandmother’s choice, I’d say she’s got good taste and she can fix me up any time!’

‘Lotty’s actually going out with someone?’ Caro swivelled round from the computer and stared at Stella. ‘She didn’t say that! Who is he?’

‘Give me a sec. I’m trying to find that photo of her.’ When the flicking failed, Stella licked her finger and tried turning the pages one by one. ‘I can never get over you being friends with a real princess. I wish I’d been to a posh school like yours.’

‘You wouldn’t have liked it. It was fine if you had a title and your own pony and lots of blonde hair to toss around, but if you were only there because your mum was a teacher and your dad the handyman, they didn’t want to know.’

‘Lotty wanted to know you,’ Stella pointed out, still searching.

‘Lotty was different. We started on the same day and we were both the odd ones out, so we stuck together. We were both fat and spotty and had braces, and poor Lotty had a stammer too.’

‘She’s not fat and spotty now,’ said Stella. ‘She looked lovely in that picture … ah, here it is!’

Folding back the page, she read out the caption under one of the photographs on the Party! Party! Party! page. ‘Here we go: Princess Charlotte of Montluce arriving at the Nightingale Ball—fab dress, by the way—with Prince Philippe.

‘Philippe, the lost heir to Montluce, has only recently returned to the country,’ she read on. ‘The ball was their first public outing as a couple, but behind the scenes friends say they are “inseparable” and royal watchers are expecting them to announce their engagement this summer. Is one of Europe’s most eligible bachelors off the market already?‘

‘Let me see that!’ Caro whipped the magazine out of Stella’s hands and frowned down at the shiny page. ‘Lotty and Philippe? I don’t believe it!’

But there was Lotty, looking serene, and there, next to her, was indeed His Serene Highness Prince Philippe Xavier Charles de Montvivennes.

She recognised him instantly. That summer he had been seventeen, just a boy, but with a dark, reckless edge to his glamorous looks that had terrified her at the time. Thirteen years on, he looked taller, broader, but still lean, still dangerous. He had the same coolly arrogant stare for the camera, the same sardonic smile that made Caro feel fifteen again: breathless, awkward, painfully aware that she didn’t belong.

Stella sat up excitedly. ‘You know him?’

‘Not really. I spent part of a summer holiday in France with Lotty once, and he was part of a whole crowd that used to hang around the villa. It was just before Dad died and, to be honest, I don’t remember much about that time now. I know I felt completely out of place, but I do remember Philippe,’ Caro said slowly. ‘I was totally intimidated by him.’

She had a picture of Philippe lounging around the spectacular infinity pool, looking utterly cool and faintly disreputable. There had always been some girl wrapped round him, sleek and slender in a minuscule bikini while Caro had skulked in the shade with Lotty, too shy to swim in her dowdy one-piece while they were there.

‘He and the others used to go out every night and make trouble,’ she told Stella. ‘There were always huge rows about it, and one or other of them would be sent home on some private plane in disgrace for a while.’

‘God, it sounds so glamorous,’ said Stella enviously. ‘Did you get to go trouble-making too?’

‘Are you kidding?’ Caro hooted with laughter. ‘Lotty and I would never have had the nerve to go with them. Anyway, I’m quite sure Philippe didn’t even realise we were there most of the time. Although, actually, now I think about it, he was nice to me when I heard Dad was in hospital,’ she remembered. ‘He said he was sorry and asked if I wanted to go out with the rest of them that night. I’d forgotten that.’

Caro looked down at the magazine again, trying to fit the angular boy she remembered into the picture of the man. How funny that she should remember that moment of brusque kindness now. She’d been so distressed about her father that she had wiped almost everything else about that time from her mind.

‘Did you go?’

‘No, I was too worried about Dad and, anyway, I’d have been terrified. They were all wild, that lot. And Philippe was the wildest of them all. He had a terrible reputation then.

‘He had this older brother, Etienne, who was supposed to be really nice, and Philippe was the hellraiser everyone shook their heads about. Then Etienne was killed in a freak waterskiing accident, and after that we never heard any more about Philippe. I think Lotty told me he’d cut off all contact with his father and gone off to South America. Nobody knew then that his father would end up as Crown Prince of Montluce, but I’m surprised he hasn’t come back before. Probably been too busy hellraising and squandering his trust fund!’

‘You’ve got to admit it sounds more fun than your average blind date in Ellerby,’ Stella pointed out. ‘You said you wanted to have fun, and he’s obviously the kind of guy who knows how to do that. You should get Lotty to fix you up with one of his cool friends.’

Caro rolled her eyes. ‘Do you really see me hanging around with the jet set?’

‘I see what you mean.’ Pursing her lips, Stella studied her friend. ‘You’d definitely have to lose the crochet top!’

‘Not to mention about six stone,’ said Caro.

She tossed the magazine back to Stella. ‘Anyway, I can’t think of anything worse than going out with someone like Philippe. You’d have to look perfect all the time. And then, when you were doing all those exciting glamorous things, you wouldn’t be able to look as if you were enjoying it, because that’s not cool. And you’d have to be stick-thin, which would mean you’d never be able to eat. It would be awful!’

‘Lotty doesn’t look as if she minds,’ said Stella with another glance at the photo. ‘And I don’t blame her!’

‘You never know what Lotty’s really thinking. She’s been trained to always smile, always look as if she’s enjoying herself, even if she’s bored or sick or fed up. Being a princess doesn’t sound any fun to me,’ said Caro. ‘Lotty’s been a good girl all her life, and she’s never had the chance to be herself or meet someone who’ll bother to get to know her rather than the perfect princess she has to be all the time.’

A faint line between her brows, she turned back to the computer and opened Lotty’s last email message. Why hadn’t Lotty said anything about Philippe then?

To: charlotte@palaisdemontvivennes.net

From: caro.cartwright@u2.com

Subject: ?????????????

You and Philippe?????????????????????????????????

Lotty’s reply came back the next morning.

To: caro.cartwright@u2.com

From: charlotte@palaisdemontvivennes.net

Subject: Re: ?????????????

Grandmère is up to her old tricks again and this time it’s serious. I can’t tell you what it’s like here. I’m getting desperate!

Caro, remember how you said you’d do anything for me when we joked about swapping lives for a while? Well, I’ve got an idea to put to you, and I’m hoping you weren’t joking about the helping bit! I really need to explain in person, but you know how careful I have to be on the phone here, and I can’t leave Montluce just yet. Philippe is in London this week, though, so I’ve given him your number and he’s going to get in touch and explain all about it. If my plan works, it could solve our problems for all of us!

Lxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Deeply puzzled, Caro read Lotty’s message again. What plan, and what did Philippe have to do with it? She couldn’t imagine Philippe de Montvivennes solving any of her problems, that was for sure. What could he do? Make George dump Melanie and come crawling back to her on his knees? Persuade the bank that the delicatessen where she’d been working hadn’t gone bankrupt after all?

And what problems could he possibly have? Too much money in his trust fund? Too many gorgeous women hanging round him?

Philippe will explain. A real live prince, heir to the throne of Montluce, was going to ring her, Caro Cartwright. Caro nibbled her thumbnail and tried to imagine the conversation. Oh, hi, yeah, she would say casually when he called. Lotty mentioned you would ring.

She wished she knew what Lotty had told him about her. Not the truth, she hoped. Philippe would only sneer if he knew just how quiet and ordinary her life was.

Not that she cared what he thought, Caro reminded herself hastily. She loved living in Ellerby. Her dreams were ordinary ones: a place to belong, a husband to love, a job she enjoyed. A kitchen of her own, a family to feed. Was that too much to ask?

But Philippe had always lived in a different stratosphere. How could he know that she had no interest in a luxury yacht or a designer wardrobe or hobnobbing with superstars, or whatever else he’d been doing with himself for the past five years? She wouldn’t mind eating in the Michelin starred restaurants, Caro allowed, but otherwise, no, she was happy with her lot—or she would be if George hadn’t dumped her for Melanie and the deli owner hadn’t gone bankrupt.

No, Philippe would never be able to understand that. So perhaps she shouldn’t be casual after all. She could sound preoccupied instead, a high-powered businesswoman, juggling million pound contracts and persistent lovers, with barely a second to deal with a playboy prince. I’m a bit busy at the moment, she could say. Could I call you back in five minutes?

Caro rather liked the idea of startling Philippe with her transformation from gawky fifteen-year-old to assured woman of the world, but abandoned it eventually. For one thing, Philippe would never remember Lotty’s friend, plump and plain in her one-piece black swimsuit, so the startle effect was likely to be limited. And, for another, she was content with her own life and didn’t need to pretend to be anything other than what she was, right?

Right.

So why did the thought of talking to him make her so jittery?

She wished he would ring and get it over with, but the phone remained obstinately silent. Caro kept checking it to see if the battery had run out, or the signal disappeared for some reason. When it did ring, she would leap out of her skin and fumble frantically with it in her hands before she could even check who was calling. Invariably it was Stella, calling to discover if Philippe had rung yet, and Caro got quite snappy with her.

Then she was even crosser with herself for being so twitchy. It was only Philippe, for heaven’s sake. Yes, he was a prince, but what had he ever done other than go to parties and look cool? She wasn’t impressed by him, Caro told herself, and was mortified whenever she caught herself inspecting her reflection or putting on lipstick, as if he would be able to see what she looked like when he called.

Or as if he would care.

In any case, all the jitteriness was quite wasted because Philippe didn’t ring at all. By Saturday night, Caro had decided that there must have been a mistake. Lotty had misunderstood, or, more likely, Philippe couldn’t be bothered to do what Lotty had asked him to do. Fine, thought Caro grouchily. See if she cared. Lotty would call when she could and in meantime she would get on with her life.

Or, rather, her lack of life.

A summer Saturday, and she had no money to go out and no one to go out with. Caro sighed. She couldn’t even have a glass of wine as she and Stella were both on a diet and had banned alcohol from the house. It was all right for Stella, who had gone to see a film, but Caro was badly in need of distraction.

For want of anything better to do, she opened up her laptop and logged on to right4u.com. Her carefully worded profile, together with the most flattering photo she could find—taken before George had dumped her and she was two sizes thinner—had gone live the day before. Perhaps someone had left her a message, she thought hopefully. Prince Philippe might not be prepared to get in touch, but Mr Right might have fallen madly in love with her picture and be out there, longing for her to reply.

Or not.

Caro had two messages. The first turned out to be from a fifty-six-year-old who claimed to be ‘young at heart’ and boasted of having his own teeth and hair although, after one look at his photo, Caro didn’t think either were much to be proud of.

Quickly, she moved onto the next message, which was from a man who hadn’t provided a picture but who had chosen Mr Sexy as his code name. Call her cynical, but she had a feeling that might be something of a misnomer. According to the website, the likelihood of a potential match between them was a mere seven per cent. I want you to be my soulmate, Mr Sexy had written. Ring me and let’s begin the rest of our lives right now.

Caro thought not.

Depressed, she got up and went into the kitchen. She was starving. That was the trouble with diets. You were bored and hungry the whole time. How was a girl supposed to move on with her life when she only had salad for lunch?

In no time at all she found the biscuits Stella had hidden in with the cake tins, and she was on her third and wondering whether she should hope Stella wouldn’t notice or eat them all and buy a new packet when the doorbell rang. Biscuit in hand, Caro looked at the clock on wall. Nearly eight o’clock. An odd time for someone to call, at least in Ellerby. Still, whoever it was, they surely had to be more interesting than trawling through her potential matches on right4u.com.

Stuffing the rest of the biscuit into her mouth, Caro opened the door.

There, on the doorstep, stood Prince Philippe Xavier Charles de Montvivennes, looking as darkly, dangerously handsome and as coolly arrogant as he had in the pages of Glitz and so bizarrely out of place in the quiet Ellerby backstreet that Caro choked, coughed and sprayed biscuit all over his immaculate dark blue shirt.

Philippe didn’t bat an eyelid. Perhaps his smile slipped a little, but he put it quickly back in place as he picked a crumb off his shirt. ‘Caroline Cartwright?’ With those dark good looks, he should have had an accent oozing Mediterranean warmth but, like Lotty, he had been sent to school in England and, when he opened that mouth, the voice that came out was instead cool and impeccably English. As cool as the strange silver eyes that were so disconcerting against the olive skin and black hair.

Still spluttering, Caro patted her throat and blinked at him through watering eyes. ‘I’m—’ It came out as a croak, and she coughed and tried again. ‘I’m Caro,’ she managed at last.

Dear God, thought Philippe, keeping his smile in place with an effort. Caro’s lovely, Lotty had said. She’ll be perfect.

What had Lotty been thinking? There was no way this Caro could carry off what they had in mind. He’d pictured someone coolly elegant, like Lotty, but there was nothing cool and certainly nothing elegant about this girl. Built on Junoesque lines, she’d opened the door like a slap in the face, and then spat biscuit all over him. He’d had an impression of lushness, of untidy warmth. Of dark blue eyes and fierce brows and a lot of messy brown hair falling out of its clips.

And of a perfectly appalling top made of purple cheesecloth. It might possibly have been fashionable forty years earlier, although it was hard to imagine anyone ever picking it up and thinking it would look nice on. Caro Cartwright must get dressed in the dark.

Philippe was tempted to turn on his heel and get Yan to drive him back to London, but Lotty’s face swam into his mind. She had looked so desperate that day she had come to see him. She hadn’t cried, but something about the set of her mouth, about the strained look around her eyes had touched the heart Philippe had spent years hardening.