скачать книгу бесплатно

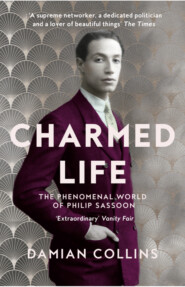

Arriving for his first term, the thirteen-year-old Philip Sassoon was an exotic figure to those English schoolboys. He had a dark complexion, as a result of his eastern heritage, and a French accent from the great deal of time he had spent with his mother’s family. In particular he rolled his ‘r’s and at first introduced himself with the French pronunciation of his name: ‘Pheeleep’. Philip had a slight build which did not mark him out as a future Captain of Boats or star of the football field; Eton was a school which idolized its sportsmen, and they filled the ranks of Pop, the elite club of senior boys. For Philip, just being Jewish made him unusual enough in the more conservative elements of society, as it aroused suspicion as a ‘foreign’ religion.

While it was well known that Philip’s family had great wealth, this was not something that would necessarily impress the other boys, particularly when it was new money. Any sense of self-importance was also strictly taboo, and likely to lead only to ridicule. To be accepted, Philip would need to master that great English deceit of false modesty.

He was placed in the boarding house run by Herbert Tatham, a Cambridge classicist who had been a member of one of the university’s secret societies of intellectuals, the Young Apostles. The house accommodation was spartan, and certainly bore no comparison with Philip’s life in Park Lane and the Avenue de Marigny. Lawrence Jones, a contemporary at Eton, where his friends called him ‘Jonah’, remembered that in his house:

no fires might be lit in boys’ rooms till four o’clock, however hard the frost outside, and since the wearing of great coats was something not ‘done’ except by boys who had house colours or Upper Boats, we shook and shivered from early school till dinner at two o’clock … we snuffled and snivelled through the winter halves … If there is anything more bleak than to return to your room on a winter’s morning, with snow on the ground to find the door and window open, the chairs on the table and the maid scrubbing the linoleum floor, I have not met it.

Unlike many other English boarding schools of the time, boys at Eton had a room to themselves from the start, which gave them a place to escape to and a space which they could make their own. This was one definite advantage and Jones recalled that ‘For sheer cosiness, there is nothing to beat cooking sausages over a coal fire in a tiny room, with shabby red curtains drawn, and the brown tea-pot steaming on the table.’

There were dangers too in these cramped old boarding houses, and in Philip’s first year at the school a terrible fire would destroy one of them, killing two junior boys.

One of the senior boys in Philip’s house was the popular Captain of the School, Denys Hatton, who took him under his wing when he started. Denys would not allow Philip to be bullied, and in return he received overwhelming displays of gratitude and admiration which at times clearly disturbed him. On one occasion when Denys was laid up in the school infirmary with a knee injury, Philip rushed to his side with lavish gifts including a pair of diamond cufflinks and ruby shirt studs. Denys received them with disgust, throwing them on to the floor, but he later made sure to retrieve them.

Philip remembered Denys’s kindness, and when he had himself risen through the school’s ranks he was similarly considerate to the junior boys. At Eton it was the tradition for the juniors to act as servants or ‘fags’ for senior students. Osbert Sitwell, the future writer and poet, fulfilled this role for Philip and they remained friends thereafter. Sitwell remembered that Philip was ‘very grown up for his age, at times exuberant, at others melancholy and preoccupied, but always unlike anyone else … And extremely considerate and kind in all his dealings.’

Among Eton’s unwritten rules was that, to become one of the club, you first had to become clubbable. Philip sought to gain favour with his contemporaries by throwing generous tea parties in his room, with the help of Mrs Skey, the house matron.

There he would amuse his guests with his great gift as a mimic and storyteller, making full use of London gossip from his parents’ social circle. He was an enthusiast of the energetic cross-country sport of beagling, he rowed for his house, and he enjoyed tennis and the school’s traditional handball game, Eton Fives. In his last year Philip would also receive the social distinction of rowing on the Monarch boat in the river pageant for the school’s annual celebrations on 4 June, in honour of the birthday of Eton’s great patron King George III.

Later in life Osbert Sitwell would state in his entry in Who’s Who that he was educated during the Eton school holidays. The education of English gentlemen at that time was traditional, limited in its curriculum and designed to mould and shape, rather than to inspire and encourage. Senior Eton masters responded to such occasional criticism by pointing out that the school regularly produced brilliant and inspirational young men, so it couldn’t be all bad. In the early 1900s, the Eton classrooms were even older and more basic than the boys’ accommodation. The future leaders of the Empire were educated in facilities that any school inspector would today close down on sight without a moment’s hesitation. Junior boys were taught in a dark, low-ceilinged, gas-lit schoolroom, with the view of the master interrupted by blackened oak pillars. It was not heated in winter, and was airless in summer. Their small wooden desks were too narrow to write at, and were carved with innumerable names of generations of boys.

The main subjects in the curriculum were Latin and Greek, with the boys required to spend many hours each week learning off by heart great tracts from Ovid and Horace, Virgil and Homer. History and maths were taught well, but science was limited and any kind of study of English poetry and literature was rare before the students’ final year. For most boys French was largely taught as a dead language, with the students undertaking written translation but not speaking French. Philip, though, was already bilingual and would twice win the school’s King’s Prize for French. As such he was included in the special conversational French classes for exceptional students, given by Monsieur Hua, a bald-headed Frenchman with a black beard who had also been called to Windsor Castle to teach King Edward VII’s grandsons.

In the evenings he would invite small groups of the boys to his rooms where they would learn to talk and gossip in French.

If the French language was a gift from his mother, so was Philip’s passion for art. Art education at Eton was generally limited to the lower boys taking drawing lessons with old Sam Evans, who would direct the pupils to sketch copies of plaster casts of classical figures. Philip took up these classes but was more fortunate to come to the attention of Henry Luxmoore, the ‘grand old man’ among Eton’s masters and a ‘lone standard bearer for aesthetics’.

Philip would join small groups of boys for Sunday teas with Luxmoore in the famous garden he had created at Eton, where they would discuss art. These informal sessions for students whom Luxmoore regarded as potential kindred spirits was the only education the boys had in the works of the great artists. Philip could contribute with knowledge acquired from his family’s extensive collection, and of course drop into conversation the news that John Singer Sargent was painting his mother’s portrait.

Having grown up around beautiful things it is not surprising that he should have developed a strong appreciation of the value of art for its own sake. At Eton, Luxmoore would help to develop Philip’s intellectual curiosity in the attempts of great artists to understand and capture beauty. Luxmoore’s own particular interest was in the works of the seventeenth-century Spanish painter Bartolomé Murillo, whose realist portraits of everyday life, including flower girls, street urchins and beggars, may have influenced Philip’s own later interest in the English ‘conversation piece’ paintings of Gainsborough and Zoffany, depicting the details of life in the eighteenth century. Murillo’s work also showed that real beauty could be found anywhere, not just in great cathedrals and palaces. Luxmoore’s passion for the art of gardening was something else that Philip would share in adult life, with both men appreciating its power to define space and create an experience of beauty.

When Luxmoore died in 1926, the Spectator magazine recalled that ‘his knowledge and sense of art and architecture made him an arbiter of taste. But his most abiding mark will be on the characters of innumerable boys and, we venture to say, of masters too. He inspired high motives and principles by expecting them. No one with a mean thought in his heart could come before Mr Luxmoore’s eye and not feel ashamed.’

Philip Sassoon’s education in aesthetics was energetic rather than passive. He developed not just an appreciation of art, but an idealized vision for life. He believed, as Oscar Wilde did, that ‘by beautifying the outward aspects of life, one would beautify the inner ones’, and that an artistic renaissance represented ‘a sort of rebirth of the spirit of man’.

Eton suited Philip Sassoon, because despite the strictures of Edwardian English society it was a place where ‘you could think and love what you liked; only in external matters, in clothes or in deportment, need you to do as others did’.

Philip was not one of Eton’s star scholars; those prizes were taken by boys like Ronald Knox and Patrick Shaw Stewart, who would go on to scale the academic heights at Oxford. He sat the examination for Balliol College, which had something of a reputation as an academic hothouse, but was not awarded one of the closed scholarships that were at Eton’s disposal. Instead he took the traditional path to Christ Church, to read Modern History.

Leading statesmen like William Gladstone and the Marquess of Salisbury had previously made the journey from Eton to Christ Church, but it also had a reputation as the home of Oxford’s more creative students. It had been the college of Lewis Carroll and of the great Victorian art critic John Ruskin; and Evelyn Waugh would later choose Christ Church’s Meadow Building, constructed in the Venetian Gothic style, as the setting for Lord Sebastian Flyte’s rooms in Brideshead Revisited, published in 1945. Fortunate students living in the beautiful eighteenth-century Peckwater Quad could have a fine set of high-ceilinged rooms in which to live and entertain with style.

Life at Oxford in those seven years before the First World War is now seen as the high summer of the British Empire, coloured by the glorious flowering of a lost generation. It is a view inevitably shaped by the immense sense of loss at the deaths of so many brave and brilliant young men in battle. Oxford was still governed, though, by a pre-First World War social conservatism and, as at Eton, Philip could not help being somewhat ‘other’. It was less than forty years since the university had first accepted students who were not members of the Church of England, and he was one of no more than twenty-five undergraduates of the Jewish faith, out of a total of three thousand at the university.

Philip had grown in confidence and stature since his early Eton days. He was sleek, athletic and always immaculately attired in clothes tailored in Savile Row. He continued to enjoy robust outdoor pursuits like beagling and was an avid swimmer and tennis player. He went out hunting with the Heythrop and Bicester, and members recalled that he always ‘looked like a fashion plate even in the mud’.

Philip was not a varsity sportsman, so would not earn the Oxford Blue that would guarantee acceptance into Vincent’s Club, but he was invited to join the renowned dining club, the Bullingdon, which was then popular with Old Etonian undergraduates who hunted.

At Oxford he also enjoyed the independence of having his own allowance to spend, and his own rooms to live in. He arranged for furniture from his parents’ Park Lane mansion to decorate his quarters at Christ Church, and once gave a seven-course dinner party with the food specially brought up by train in heated containers from a restaurant in London. Despite his father’s hope that Philip would start to mark out a future for himself in politics, he did not trouble the debaters at the Oxford Union Society, the training ground for generations of would-be leaders of nations. Although a confident performer in private company he remained a nervous public speaker and could not hope to compete with the Union’s leading lights, such as fellow Old Etonian Ronald Knox.

At Oxford, Philip’s circle of friends was drawn not from his own college, but mainly from his Old Etonian contemporaries at Balliol, men like Charles Lister, Patrick Shaw Stewart, Edward Horner and Julian Grenfell. Apart from Horner, they did not fit the mould of the traditional English gentleman, whose place and role in the world was certain. Lister had caused a stir at Eton by joining the Labour Party, a genuinely radical step in the eyes of early Edwardian society. He’d also participated actively in the school’s mission to the poor in Hackney Wick in the East End of London. Shaw Stewart was academically brilliant and very ambitious but, without any real family money, was required to make his own way in the world. He was fixed on making a fortune in the City, before embarking on his own career in public life. Grenfell was someone whom Philip had grown up with, even if they had not become particularly close. Philip and his family had been frequent guests at Taplow Court where Julian’s mother Lady Desborough, a close friend of Aline Sassoon, was a renowned hostess. Julian’s first London dinner party had been at the Sassoons’ home in Park Lane, the evening before the Oxford and Cambridge University Boat Race in 1907, and his younger brother Billy had been to stay at the Avenue de Marigny earlier that year.

Yet Philip and Julian were cut from very different cloth. Julian was 6 foot 2 and made for battle. His aesthetic interests lay in the pursuit of physical perfection through the training of his own body as an athlete and boxer. Lawrence Jones, a contemporary at Eton and Balliol, remembered that

There was something simple and primitive in [Julian] that was outraged by the perfection of well-bred luxury at Taplow … He felt that there was something artificial and unreal in [his mother’s] deft manipulation of a procession of week-end parties, lightly skimming the cream from the surface of life … Julian had a passion for red-blooded down-to-earthiness, for action and adventure, and, with youthful intolerance, fiercely resented the easy, cushioned existence of Edwardian society.

These emotions led to frequent arguments with his mother, and were also evident in his up-and-down relationship with Philip, whose own tastes were closer to Lady Desborough’s. Julian wrote a mocking letter to his mother from Oxford, faking a new interest in the more refined tastes she hoped he might develop:

I went and did a soshial [sic] last night to widen my circle of friends and my general horizon: the Bullingdon dinner – all the pin heads there! They are such good fellows!! and now I know what a miserable fool I’ve been shutting myself away from my fellow men, but thank God it is not too late! and I believe that last night I laid the foundations for some golden friendships which will blossom out and change and colour the whole of my life. Do you know a man called Philip Sassoon?

Julian kept an Australian stock whip, and once used it after a party in Philip’s luxurious rooms to chase him around Christ Church’s Tom Quad, cracking the whip to within inches of Sassoon’s head, crying out, ‘I see you, Pheeleep,’ mocking his French accent. Julian would also call out ‘I see you, Pheeleep’ if he spotted him in the Balliol Quad, causing Philip to scurry for the gatehouse or a nearby staircase entrance. Their friendship, which developed at Oxford, was largely based on their mutual interest in rigorous outdoor pursuits. Lawrence Jones remembered that they ‘both had a passion for beauty, as well as for getting things done’.

Julian and Philip were complex personalities who defied preconceived ideas of their characters. Julian was the rough man who was also developing into an increasingly accomplished poet. Philip was the aesthete who jumped fences and muddy ditches in perfectly tailored buckskin breeches, and played opponents into the ground at tennis.

In July 1908, at the end of Philip’s first year at Oxford, he attended a large summer party at Taplow Court given by Lady Desborough, to mark the final appearance by Julian’s brother Billy in the Eton versus Harrow cricket match, with guests including the new Liberal Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, and the Conservative leader, Arthur Balfour. Philip then departed to spend part of the vacation in Munich to improve his German. He lodged with a baron who provided rooms for young gentlemen, often those aspiring to work in the diplomatic service and looking to perfect their languages. Sassoon shared his quarters with John Lambton, who was just a few years older than him but already much the same as the rather staid Earl of Durham that he would become.

Lambton was friendly with the American novelist Gertrude Atherton, who was living in the city at the time, and Philip joined their group. There could not have been a greater contrast between the irrepressible Philip and the stolid Lambton. Gertrude remembered that Philip was ‘as active as Lambton was Lymphatic; he might indeed have been strung on electric wires, wanted to be doing something every minute … To sleep late was out of the question with that dynamo in his room at nine in the morning demanding to be taken somewhere.’

Along with Gertrude’s niece Boradil Craig, they embarked on an energetic tour of the sights and treasures of Bavaria, including Ludwig II’s extraordinary Romanesque Revival castle of Neuschwanstein. Ludwig had created a romantic fantasy of pre-Raphaelite splendour high in the rugged hills above Hohenschwangau. It was inspired by the world of German knights, honour and sacrifice captured in the works of Richard Wagner, whom Ludwig worshipped. Philip Sassoon toured every corner of the castle, devouring in detail the architecture and decor, and admiring the personal artistic statement that Ludwig had made. Philip’s great-grandfather David had similarly built his own palace at Poona, and the young Sassoon would later fashion a new estate in Kent at Port Lympne, which would be his greatest creative legacy.

In the evenings the group would often attend Munich’s Feldherrnhalle opera house, and on one occasion Philip and Boradil danced in the open air in Ludwigstrasse, on a platform before a replica of Florence’s Loggia di Lanza. Gertrude recalled that Philip ‘in an excess of high spirits kicked off [Lambton’s] hat and played football with it [and] he was highly offended. Despite his lazy good nature he could be haughty and excessively dignified, and all his instinct of caste rose at the liberty. But Young Sassoon was irrepressible. Hauteur and aristocratic resentment made no impression on him.’ Gertrude thought Philip ‘a nice boy and an extremely brilliant one, the life of our parties’.

Philip returned to his studies at Oxford, working diligently if not with huge distinction, and graduated after four years with a second-class honours degree in Modern History, specializing in eighteenth-century European studies. He’d also signed up at Oxford, with his father’s encouragement, as a junior officer in the East Kent Yeomanry, which was the local reservist regiment for Edward’s parliamentary constituency of Hythe. Edward, always thinking of a future career for his son in public life, told Philip that such a move would be ‘useful in other ways later on’.

A number of Philip’s Oxford friends joined various respectable institutions after graduating. Julian Grenfell became a professional soldier, Charles Lister went to the Foreign Office, and Patrick Shaw Stewart followed his first-class degree with a fellowship at All Souls and a position at Baring’s Bank. It was not clear what Philip would do next. He did not need to make money, and there was no requirement that he should take an active interest in the family firm. He would accompany his father on occasional visits to the office of David Sassoon & Co. in Leadenhall Street, and also to some political meetings and speaking engagements in the constituency.

However, from the summer of 1909, halfway through Philip’s Oxford career, and for the next ten years, death did more than anything to shape the course of his life. Philip would lose in succession his parents, his surviving grandparents and then, in the First World War, a great number of his friends. With death as his constant companion, he could not have been blamed for being imbued, as he would later remark, ‘with a fatalism purely oriental’.

By this he meant the idea that life is preordained, and that nothing can be done to avoid the fate for which you are destined. Philip would certainly follow the path his parents had set out for him, but his response to each of the blows which death delivered shows a determination to rise to the challenges they presented, and not to be cowed by them.

In early 1909, Philip’s beloved mother Aline was diagnosed with cancer, and her health failed fast. On 28 July, aged just forty-four, she died at her family’s home in the Avenue de Marigny and was buried alongside her grandfather in the Rothschilds’ family tomb at Père Lachaise. The whole family was devastated, and Aline’s friends tried to rally around the children. Frances Horner wrote to Philip in Paris immediately after her friend’s death to remind him that ‘You will return to a country that loved her and will always love her children.’

Philip was given the string of pearls that Edward had presented to Aline on their wedding day, in the expectation that he would one day give them to his own bride. Instead he often kept them in his pocket, rubbing them occasionally – in order, he would tell friends, ‘to keep them alive’.

Philip believed, as he would later tell Lady Desborough, that the greatest burden of sorrow was felt for those who had to live on without Aline, rather than for his mother herself, whose life had been so tragically cut short.

Edward Sassoon never recovered from the loss of his wife, and became a withdrawn figure, remote even from other members of the family. In the winter of 1911 he was involved in a collision with a motor car on the Promenade de la Croisette in Cannes and remained badly shaken by the accident. His health further deteriorated in the new year, as a result, it was discovered, of the onset of cancer. Just as with Aline, the end came all too rapidly and he died at home in Park Lane on 24 May 1912, a month short of his fifty-sixth birthday. His coffin was enclosed in the Sassoon mausoleum in Brighton, alongside that of his father, Albert. The twenty-three-year-old Sir Philip, now the third baronet, and his seventeen-year-old sister Sybil were left with the grief of having lost both parents in less than three years. Their maternal grandparents had also both died, in 1911 and 1912, first Baron Gustave de Rothschild and then their grandmother, to whom Sybil had been particularly close. Frances Horner again wrote to Philip: ‘You have both been so familiar with grief and suffering these two years [that it] must have [made] a deep mark on your youth.’

Philip did not receive the normal orphan’s inheritance, as tragic circumstances had contrived to make him one of the wealthiest young men in England. Along with his title, he received an estate from his parents worth £1 million, including the mansion at 25 Park Lane, a country estate and farmland at Trent Park, just north of London, and Shorncliffe Lodge on the Kent coast at Sandgate. There was also property in India, including his great-grandfather’s house at Poona, and Edward’s shares in David Sassoon & Co. These came with the request in his father’s will that he should never sell them to outsiders and thereby weaken the family’s control of the business. He honoured Edward’s request and remained a major shareholder, although he never took much of an interest in the business. Philip took up residence alone at 25 Park Lane. It was felt that brother and sister should not live together, so Sybil moved in with their recently widowed great-aunt, Louise Sassoon, at 2 Albert Gate near Hyde Park.

Edward left one further gift for Philip, for whom he had such high hopes, stating in his will that it was his ‘special wish’ that his son should ‘maintain some connection with my parliamentary constituency’. This request merely emphasized an undertaking that he had sought from Philip before he died. Sybil remembered that when their father was ‘very ill and they knew he was not going to recover, they asked my brother to take his place’.

It was also reported in the newspapers the day after Edward died that ‘it is freely stated that Mr Philip Sassoon … will be put forward’ as parliamentary candidate for Hythe.

It was not unusual for sons to follow their fathers into politics, but the final decision on the candidate would be made by the party leader, Andrew Bonar Law. The former MP Sir Arthur Colefax was also staking a claim to the seat and his experience was much greater than Philip’s, who had made his first public political speech just a few weeks previously, an address to the Primrose League

in opposition to Home Rule for Ireland. Bonar Law was advised, however, to give the young Sassoon the chance to stand. This was not purely down to sentiment, but was chiefly because of the large financial contributions that the Sassoon and Rothschild families had made to the local constituency party funds over many years. Both Philip and Colefax addressed the meeting at Folkestone town hall where the local Conservative Party adopted their candidate, but it was clear that the overwhelming majority were with Sassoon.

Philip’s selection meant that there was no time to grieve for his father, as the by-election was to be held on 11 June. He threw himself into the campaign, building on the goodwill people felt towards Edward, and working hard to fulfil his father’s final wish that he should be elected. In his election address Philip set out his credentials as the Conservative and Unionist candidate: opposing home rule as something which would in his opinion cause grave troubles in Ireland, supporting tariff reform to give preference to goods imported from the British Empire, and calling for further investment in new battleships for the Royal Navy.

He could certainly rely on the support of the Folkestone fishermen, who had carried Edward Sassoon’s banner and party colours on their boats moored in the harbour at the general election in 1910, and did the same during Philip’s campaign. They were set against the Liberal government’s free-trade policies that allowed French fishermen to land their fish in Folkestone tariff free, while British vessels were charged if they brought any of their catch into French ports. Philip also received backing from the licensed victuallers in the constituency, continuing the traditional support the Tories enjoyed from the drinks industry.

He upset some of the more traditionalist Conservative MPs during the by-election by supporting the suffragette campaign for votes for women. At his first public meeting of the campaign, he was accused by some in the audience of being too young, but the newspapers reported that he ‘promised to grow out of that if they gave him the chance’.

His performance at the meeting was also reported by the local newspapers as an ‘amazing success’.

On polling day the weather was fine, which was good for encouraging voters to turn out and, just in case, Philip’s campaign used motor cars to drive their supporters to the polling stations. The voters of the Hythe constituency safely returned to Parliament the young man they had known since he was a boy, with a majority almost exactly the same as his father had enjoyed at the previous general election. At the age of just twenty-three, Philip also had the distinction of being the ‘baby of the House’.

Contemporaries of Philip’s such as Patrick Shaw Stewart were working to make their fortune, with the hope later of taking a seat in Parliament. Sir Philip Sassoon had now secured both through inheritance. Edward Sassoon’s vision of the life that was to open out for Philip had come to pass, but while the efforts of his ancestors could help to deliver him to the House of Commons, he would have to make his own reputation once there.

Max Beerbohm, the well-known satirist of the politicians of the day, depicted a sleek and impassive Philip Sassoon sitting cross-legged in the lotus position on the green benches, between two large, booming and red-faced Tories.

He called the caricature Philip Sassoon in Strange Company. Philip was very different in appearance and manner from the knights of the shires and veteran soldiers of colonial wars who adorned the House of Commons. There were also very few Jewish MPs, and over 90 per cent of the Conservatives were practising members of the Church of England. But Parliament was starting to change with more businessmen and middle-class professionals, as well as the growing representation of workers and trade unionists from the Labour Party. The House of Commons Philip entered in June 1912 featured some of the greatest names in the history of that chamber, including statesmen like David Lloyd George, Arthur Balfour and Winston Churchill. It was also a time of political uncertainty as the Liberal government led by Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, whose wife Margot had been a close friend of Philip’s mother, was beginning to run into trouble. There had been Lloyd George’s great and controversial ‘People’s Budget’ in 1909, followed by the constitutional crisis over reform of the House of Lords, and the ongoing and intractable problems of the government of Ireland. The Conservatives had been in opposition for over six years, but they had high hopes of getting back into power at the next election.

Philip waited until November 1912 to make his maiden speech, speaking against the government bill on Irish home rule. Max Aitken (later Lord Beaverbrook

), the Canadian businessman, MP and newspaper proprietor, remembered that ‘It was an indifferent performance but it brought forth a flood of notes of congratulations not because he had made a good speech but because he had big houses and even bigger funds to maintain them.’

Philip looked to put these to good effect as well, by hosting a grand lunch at Park Lane before the great Hyde Park demonstration in support of Ulster loyalism, with guests including the Unionist leader, Sir Edward Carson, and senior Conservatives like Lord Londonderry, F. E. Smith and Austen Chamberlain. Philip’s Unionist credentials were further established when it was reported that at a speech in Folkestone he had suggested that he would pay for a ship to take local army reservists to Ireland to support the cause of Ulster remaining free from the interference of home rule government in Dublin – although it was a promise that he later denied having made.

These actions may reflect his early ambitions in politics and a desire to make a good impression, rather than a genuine conviction on his part. He was trying to be helpful in aligning himself with issues close to the heart of the leadership of the Conservative Party, but he otherwise made no great impression in Parliament in his first two years in the House of Commons. He certainly became much more liberal in his views on issues like Irish home rule after the war.

The years 1912 and 1913 marked a turning point in Philip’s life, and that of his sister Sybil. With their parents gone, youth had ended and adult life had been thrust upon them. This also brought them closer together. Sybil had been educated in Paris, while Philip was at school in England. Now they would both live in London. In 1913 Philip and Sybil had individual portraits painted by the family friend, John Singer Sargent, who captured their beauty and poise, presenting them both on the brink of fulfilling their youthful promise. More interesting was a second portrait Philip commissioned from his friend the young artist Glyn Philpot. In this darker painting Philpot depicts Sassoon dressed in the same formal clothes as in the Sargent portrait, but instead of looking away and into the distance, Philip’s head is turned and lowered a fraction to look at us. While still elegant, he appears a more human, lonely and less certain figure, carrying the weight of the responsibilities that have been placed upon him.

On 6 August 1913 Sybil, at nineteen, was married after a brief courtship to George, Earl of Rocksavage, the dashing heir of the Marquess of Cholmondeley. Philip had introduced Sybil to ‘Rock’; they had known each other through their mutual friend Lady Diana Manners. Sybil’s marriage added to Philip’s relative isolation at this time. She would depart on a honeymoon of almost a year in India, and when they returned set up home at Rock’s family estate in Norfolk, Houghton Hall, and their townhouse at 12 Kensington Palace Gardens. The marriage also caused a severe rift with many of their Jewish relations, particularly the Rothschilds, who took exception to Sybil marrying outside their religion. Philip gave his sister away, and their great-aunt Louise Sassoon and cousin David Gubbay were witnesses, along with Rock’s father, the Marquess of Cholmondeley. None of Sybil’s Rothschild relations attended the ceremony and they would have no contact with her for many years. The wedding was a quiet affair, and took place at Prince’s Row register office, off Buckingham Palace Road in central London. The ceremony lasted only a quarter of an hour and there were no more than ten guests, who were themselves outnumbered by the pressmen and photographers waiting for them outside.

Before her marriage, Sybil had often accompanied Philip to parties and West End first-night performances. She had also supported him at dinners and the entertainments he gave at home at Park Lane. Philip never married, and would often insist that he had been so spoilt by his charming sister that no other woman could match up to her. However, while there is no definitive proof either way, the suspicion has always been that the real reason why Philip Sassoon never married was that he was gay.

Homosexuality remained illegal in the United Kingdom until 1967, and even the word itself was considered taboo during Philip’s lifetime.

He was in any case a very private man who did not like to discuss his personal affairs, but for it to have been generally known that he was gay would have caused a scandal. The writer Beverley Nichols recalled that ‘there were still a large number of people – particularly in high places – to whom the whole of this problem was so dark, so difficult and so innately poisonous, that they instinctively shut their eyes to it’.

In 1931, when King George V was confronted with the news that Earl Beauchamp, a friend who had carried the Sword of State at his coronation, was in danger of being exposed as a homosexual, he exclaimed, ‘I thought men like that shot themselves.’ The Earl escaped prosecution but was required to live most of the rest of his life in exile from England.

,

Yet the trial of Oscar Wilde for ‘gross indecency’ in 1895 showed that just because homosexuality was illegal, that didn’t mean it was unheard of, even if it was ‘the love that dare not speak its name’.

In fact after the First World War in ‘university circles’ Oscar Wilde was considered to be something of a ‘martyr to the spirit of intolerance’.

The writer Robert Graves, seven years Philip’s junior and a friend of his distant cousin Siegfried Sassoon, believed that at that time ‘Homosexuality had been on the increase among the upper classes for a couple of generations,’

and in part he blamed the public school system. Graves also discussed homosexual experiences in a very matter-of-fact way in his memoir Goodbye to All That. Eton was considered to be ‘perhaps the most openly gay school of the era’,

but Philip Sassoon’s contemporary Lawrence Jones believed that at Eton ‘homosexuality [was] a mere substitute for heterosexuality. It would not exist if girls were accessible. It was not carried beyond that leaving day.’

This idea was also expressed by another Old Etonian friend of Philip’s, Lord Berners, who wrote in his memoirs:

There can be no denying that in the Eton of my time a good deal of this sort of thing went on, but to speak of it as homosexuality would be unduly ponderous … I can only say that, in all cases of which I have been able to check up on the subsequent history, no irretrievable harm seems to have been done. Some of the most depraved of the boys I knew at Eton have grown into respectable fathers of families, and one of them who, in my day, was a byword for scandal has since become a highly revered dignitary of the Church of England.

Many of Philip’s friends in the inter-war period were, however, either gay or bisexual, including Berners himself, Glyn Philpot, Philip Tilden, Bob Boothby, Cecil Beaton, Rex Whistler, Noël Coward and Lytton Strachey. During a First World War military service tribunal, when Strachey was asked, ‘Tell me, Mr Strachey, what would you do if you saw a German soldier trying to violate your sister?’, he famously replied, ‘I would try to get between them.’

Sassoon was certainly at home in the private and bohemian world these men enjoyed, but he also had many close friendships with women, in particular with the writers Marie Belloc Lowndes and Alice Dudeney, and the garden designer Norah Lindsay. These relationships were not romantic, mostly based on mutual interests and an easy personal rapport. Alice Dudeney did note one occasion in her diary while staying with Philip in Park Lane, when he was ‘very restless’, and told her, ‘I’m one of those people who can’t say things. I want helping out.’ Alice recalled that, at the end of their conversation, Philip ‘just laughed and stooping kissed me – for the first time. I was very much stirred as – clearly – was he.’

There was certainly no affair between Philip and Alice, who was by her own admission old enough to be his mother, but this episode gives an insight into the difficultly that he had in expressing his feelings towards others. This could have been the result not just of his Edwardian childhood, but also of the loss of his parents before he had reached emotional maturity.

Philip Sassoon’s surviving personal papers provide little concrete evidence of his private life. In 1919 he kept a travel diary of a tour of Morocco and Spain he made with a friend referred to only as ‘Jack’, who had apparently been a fellow staff officer at General Headquarters during the First World War. There are also a few undated letters to Jack, with one including this passage, heavy with romantic overtones, ‘So you waited all the day & all the evening to ring me up … But I’ll be even with you. I’ll ring you up tomorrow morning – very early … before even the rosy fingered dawn has caused your white pyjamas to blush … I’ll wait until you are weak unwoken & at my mercy.’

Whatever the truth about Philip’s personal life, the one thing we can say with certainty is that while he had close and loyal friends, there was no one whom he shared his life with romantically over any meaningful period. There was no special partner whose relationship with him could be understood, if not acknowledged. His personal life was something that he shut away from the world; it was a part of himself that he sought to hide. One of the lessons he had learnt at Eton was that, while you could be whoever you wanted to be, there were still expectations of external conformity in Edwardian England. However, in private, and particularly at the estate he created for himself at Lympne, Philip, according to Bob Boothby, ‘gave freer rein to the exotic streak that was in him’.

Philip began work on the estate shortly after his father’s death, when he sold Shorncliffe Lodge and purchased 270 acres of farmland at Lympne, commanding excellent unbroken views of Romney Marsh and the English Channel beyond. The location was probably the best on the south Kent coast, and the whole estate was set into a secluded natural amphitheatre, created by an ancient cliff line. Philip was attracted not only to the topography of Lympne, but to its history as well. The estate marked the site of an old Roman port, Porta Lemanis, that had slowly transformed over the last thousand years into a hilly bank, as the sea had withdrawn and the wide flat marshes formed below. Philip loved the idea of his new estate having such old foundations, rather like the history of his own family.

He appointed a fashionable architect to design the mansion, Herbert Baker, who was best known at the time for his work for Cecil Rhodes in South Africa

and had only just moved his practice to London. Sir Herbert chose a Dutch colonial style, similar to designs he had used in South Africa, with the house gable-ended and facing the sea. Philip requested that older bricks be used to give softer tones to the appearance of the house and also to make it look longer established in its setting. Years later, when the gardens had been created and Philip opened up the estate to occasional public tours to raise money for deserving charities, he delighted in retelling the remark about Port Lympne he had overheard from one of the guides, that it was ‘All in the old world style, but every bit of it sham.’

Although the main structure of the mansion was completed in 1913, further design work on the house and grounds would be interrupted by the approaching war in the summer of 1914.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: