скачать книгу бесплатно

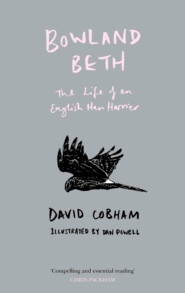

Bowland Beth: The Life of an English Hen Harrier

David Cobham

Dan Powell

The story of the short, tragic life of Bowland Beth – an English Hen Harrier – which dramatically highlights the major issues in UK conservation.The Hen Harrier has become the conservation cause célèbre in the UK – with only three nesting pairs in England it is seen as a totemic species in the battle between the conservationists and the ruralists. Extensive research has revealed that persecution is possibly the major issue highlighted by the death by shooting of a Hen Harrier called Beth. David Cobham has been at the centre of this research. In Bowland Beth he follows the short life of this Hen Harrier, interweaving her story with the story behind the species’ plight.Following the style of Henry Williamson’s Tarka the Otter and Fred Bodsworth’s Last of the Curlews, Cobham has dramatized Bowland Beth’s short life between 2011 and 2012, entering her world to show what being a Hen Harrier today is like. He immerses himself not only in the day-to-day regimen of her life, the hours of hunting, bathing, keeping her plumage in order and roosting, but also the fear of living in an environment run to provide packs and packs of driven grouse for a few wealthy sportsmen to shoot.As one of the key players in this emotive debate, David Cobham is uniquely placed to reflect on Beth’s life and tragic death. In this powerful narrative, he provides us with a profound story which helps to illuminate the larger implications of the species’ decline, highlighting the urgent need for conservation efforts to reverse this.

COPYRIGHT (#u3fb54f4c-625e-5c08-ba2b-589013b60068)

William Collins An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://williamcollinsbooks.com/) This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017 Copyright © David Cobham 2017 Illustrations (including cover artwork) by Dan Powell David Cobham asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008251895 Ebook Edition © August 2017 ISBN: 9780008251925 Version: 2017-07-11

(#u3fb54f4c-625e-5c08-ba2b-589013b60068)

For Stephen Murphy,

who guards the flame that

keeps alive the future of our

English hen harriers.

CONTENTS

Cover (#u6ff099e3-99f4-5452-a5db-65b799148463)

Title Page (#u405ee35f-6073-5d60-8aaa-f9fe79b93da6)

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Bowland Beth (#u65df2d73-40ab-5c8f-8ca7-caee5292df6c)

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Publisher

(#u3fb54f4c-625e-5c08-ba2b-589013b60068)

Bowland Beth, named after the Forest of Bowland where she was bred, was an exceptional hen harrier. Some harriers, when near to fledging, stand head and shoulders above the rest of the brood. They are bigger, their plumage is glossier and richer in colour, their eyes are brighter and they fledge ahead of their siblings. Beth was one such.

Following the style of Henry Williamson’s Tarka the Otter and Fred Bodsworth’s Last of the Curlews, I have dramatised Beth’s short life between 2011 and 2012, trying to enter her world to show what being a hen harrier today is like. I have immersed myself not only in the day-to-day regimen of her life – the hours of hunting, bathing, keeping her plumage in order and roosting – but have also attempted to express the fear of living in an environment managed to provide packs and packs of driven grouse for a few wealthy people to shoot for sport.

I hope that by dramatising Bowland Beth’s life I can rally another group of conservationists to join other groups already working hard to challenge those who are determined to illegally exterminate English hen harriers in the interests of driven grouse shooting.

Nearly fifty years ago I made a film of Tarka the Otter, and when it was finished we held a special press show for children, mostly teenagers. Afterwards I asked the audience to come forward and ask questions. Mostly they wanted to know how we made the bubbles and blood in the river. Finally, I was left with one teenaged girl standing before me. When I asked her whether she had liked the film, she said: ‘The otter died. It made me cry.’ To her astonishment I replied: ‘That’s wonderful. You felt something.’

I’m often told that my film of Tarka played an important role in getting otter hunting banned in England and Wales in 1980. Can this dramatised version of Beth’s life awaken similar emotions in people’s hearts and compel them to stand up and deplore in the strongest terms the illegal persecution of the few remaining breeding hen harriers in England? I hope so.

I have been able to dramatise Beth’s life because she was fitted with a satellite tag, and the moment she fledged she was tracked as she sped off to a grouse moor at Nidderdale thirty miles away. A select few watched with delight and alarm as she foraged over a wider and wider area. She survived the winter, and in late spring her hormones kicked in and she started searching high and low for a mate. Her journeys up into the wilds of Scotland made her a national celebrity. On one journey north she covered 125 miles in just eight and a half hours, but without fail she returned to where she had been fledged in the Forest of Bowland.

I knew about the Forest of Bowland because my wife Liza had visited it whenever she could when she was performing in plays at the Grand Theatre in Blackpool. Each time she came back she was bubbling over at the number of harriers she had seen and how kind Stephen Murphy, Natural England’s hen harrier project officer in Bowland, had been in showing her round.

Now, on 24 May 2012, I was going to see Bowland myself. I was researching for a book I was writing on the state of our birds of prey in Britain today and my companion was Eddie Anderson, whom I had known for nearly fifty years. When I first met him he was a gamekeeper. Eventually, after seven years, he gave up gamekeeping and forged a fine career making programmes for Anglia TV and BBC East.

We travelled by train from Norfolk. At Clitheroe, our destination, we were met by the late Mick Carroll, one of Stephen Murphy’s most dependable hen harrier watchers. He was going to drive us around Bowland, so we got into his car and he whisked us off to The Hark to Bounty pub in Slaidburn, where we were booked in for two nights.

We had a brief meeting with Stephen Murphy after breakfast. He promised to show us around the following day and then handed us over to Bill Hesketh and Bill Murphy, Stephen’s local, highly regarded harrier watchers. The rain had cleared, and the fells and moorland sparkled like a newly minted coin.

The rolling hills were dominated by a patchwork of green sprouting heather set against lower areas of grass split up into tiny fields by fences and stone walls, and I could quite understand why the place had been named an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, a European designation that recognises the importance of its heather moorland and blanket bog as a special habitat for upland birds.

The wild, desolate landscape is an excellent location for bird watching. Curlew, golden plover, oystercatchers and snipe are all found here, and migrating dotterel pass through in spring and autumn. The summer population of breeding curlew is one of the most buoyant in England, and short-eared owls can regularly be seen hunting in daylight for their favourite prey, short-tailed field voles.

Three important birds of prey breed in the Forest of Bowland: the merlin, our smallest bird of prey and not much bigger than a mistle thrush, the much larger peregrine falcon, which, with its 200 mph scything stoop, has been described as the most successful bird in the world, and the hen harrier. The hen harrier is the symbol of the Forest of Bowland and used to be seen regularly as it floated low over moorland hunting for small birds and field voles.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: