Полная версия:

Tai Chi: A practical approach to the ancient Chinese movement for health and well-being

Illustrated Elements of Tai Chi

Angus Clark

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Preface

How to Use this Book

Historical Origins

The Birth of Tai Chi

A Healing Art

Seven Qualities

Seven Steps to Progress

Movement, Health, and Body Awareness

The Skeleton

The Muscles

Body Alignment

Stability and Mobility

Body Shape and Posture

Inside the Body

The Circulation

Digestion and Elimination

Sensory Systems

Breathing

The Energy Centers

Preparing for Practice

Moves and Postures

The Language of Tai Chi Movements

Eight Basic Postures

The Stances

Stepping

Balanced Walking

Key Moves

Warm-Up Movements

The Complete Short Form

Beginning

Ward Off Left and Ward Off Right

Rollback

Press, Push

Single Whip

Lifting Hands

Shoulder Stroke

White Crane Spreads Wings

Brush Left Knee and Push

Play Guitar

Brush Left Knee and Push (2)

Punch

Withdraw and Push

Crossing Hands

Embrace Tiger, Return to Mountain

Rollback, Press, Push, and Single Whip

Punch Under Elbow

Step Back to Repulse Monkey

Diagonal Flying

Waving Hands in Clouds

Single Whip

Squatting Single Whip

Golden Rooster Stands on One Leg

Separate Right Foot

Separate Left Foot

Brush Knee and Push, Needles at Sea Bottom

Iron Fan

Turn Body, Chop, and Push

Bring Down and Punch(2)

Kick with Heel

Brush Right Knee and Push

Brush Left Knee and Punch Downward

Ward Off Right

Fair Lady Weaves the Shuttle (1)

Fair Lady Weaves the Shuttle (2, 3, and 4)

Ward Off Left

Squatting Single Whip

Step Forward to the Seven Stars and Step Back to Ride Tiger

Turn and Sweep Lotus

Bend Bow to Shoot Tiger

Punch (3)

Withdraw and Push and Crossing Hands

Completion

Branching Out

Working with a Partner

A Fighting Art

Cultivating Energy

Tai Chi for Life

Nature and the Elements

Freestyle Movement

Tai Chi at Work

Tai Chi at Leisure

Achieving Self-Fulfillment

Growing and Changing

Tai Chi Experiences

Styles and Schools

Further Reading/Useful Addresses

Index

Copyright

About the Publisher

Preface

TAI CHI IS a system of exercises or movements to promote health and longevity, and a comprehensive system of self-defense. Its roots are in China, where it evolved over many hundreds of years as a martial art and as a system of self-development. In the past, many of its techniques were preserved for generations as clan or family secrets, but very gradually, knowledge of the art spread throughout China. Now at the start and end of every day in villages, towns, and cities all over Chinese Asia, people can be seen practicing the slow, graceful movements of tai chi in courtyards, squares, and parks.

At dawn and as the sun sets in the evening, Chinese people go out to practice tai chi.

Tai chi was carried to the West in the 20th century, both by Westerners who had studied under Chinese masters, and by Chinese teachers who moved to the West. Nowadays, tai chi is well known in all Western countries, and a wide spectrum of people all over the world practice it regularly. In the West health organizations, schools, colleges, and even businesses now incorporate tai chi into their curricula and their training programs.

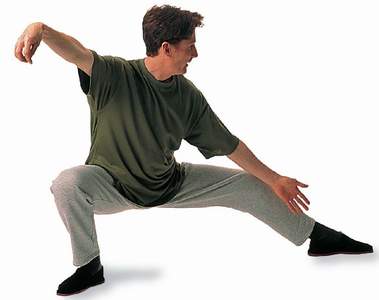

A cascade of cosmic energy sweeps through the body in the Squatting Single Whip posture.

Tai chi is a multidimensional art form that has the capacity to touch several important levels in the life of anyone who embarks on its exploration. Tai chi is not just about health or about self-defense, but about the development of the whole individual—body, mind, and spirit. This book will introduce you to tai chi as a system of movement with a variety of health, fighting, and self-development aspects. The roots of tai chi are ancient, but its principles remain applicable in the highly pressurized modern world.

How to Use this Book

Illustrated Elements of Tai Chi is a comprehensive introduction to an ancient Eastern practice that is becoming more and more popular in the West in response to the pressures of modern life. Tai chi is a holistic healing art that embraces body, mind, and spirit. It improves physical and mental well-being through posture training and exercising all parts of the body, combined with encouraging greater awareness of the links between body and mind. Practiced regularly and with dedication, tai chi becomes a system of self-development and encourages a flowering of personal creativity.

Historical Origins

TAI CHI IS rooted in the rich soil of ancient Chinese thought, which is based on observing the way things work in nature. The art embodies the concept of continuous change from one extreme to the other as expressed in the ancient book of wisdom, the I Ching: “When the sun has reached its meridian, it declines, and when the moon has become full, it wanes.” Tai chi stems from the ancient philosophy of Taoism, which arose at a time when China’s earliest martial traditions were emerging, among agricultural peoples whose lives were frequently disrupted by wars waged by contending states. And it was founded on the principle of following the natural way or Tao – the ancient philosophy of Taoism.

The Taoist philosopher Lao Tzu is said to have been Official Archivist of the State of Chou (1st century B.C.E.).

TAOIST PHILOSOPHY

The first written records of tai chi practice do not appear until the end of the first millennium C.E. However, the art is known to have been developed perhaps a thousand years earlier by Taoist recluses who retreated from the world to mountain hermitages to contemplate the meaning of action by studying nature.

Taoism is an ancient Chinese system of thought that attempts to understand the laws governing change in the universe. The Tao, or Way, is the way the universe works, the natural way of things, from the way the clouds form and disperse to the way a person behaves.

The early Taoists sought to cultivate the Tao within themselves. Taoism centers on the concept of effortless action and the power it engenders. Water symbolizes the idea of strength in weakness; it accepts the lowest level without resistance, yet it wears down the hardest obstacles simply by flowing around them. Striving is the antithesis of Taoist action: understanding springs from spontaneous creativity, not from mental or physical effort.

Ideas about the Tao were eventually set down in writing in the Tao Te Ching (Classic of the Way and Virtue), the principal text of Taoism, an anthology of writings produced in about 300 B.C.E. (often referred to as the Lao Tzu).

The philosophers of ancient China sought to make suggestions that might generate ideas and unanswered questions in the mind. Taoist writings are full of paradoxes and contradictions intended to challenge limited and inhibiting views on life, and to open the perceptions.

Taoist thought pervades tai chi. “Plants when they enter life are soft and tender,” says the Lao Tzu. “When they die they are dry and stiff… The hard and strong are companions of death. The soft and weak are the companions of life.” In tai chi, learning the qualities of softness and understanding its power are essential parts of practice.

TAI AND CHI

In Chinese, the characters for “tai” and “chi” express a double superlative, often translated as “Supreme Ultimate” or more simply as “cosmos.” Tai chi is said to have been born from wu chi, the Great Void, the original state of cosmic emptiness. With the birth of tai chi, stillness changed into movement or energy. This movement was generated by the interplay of the opposing yet complementary forces of yin and yang. Tai chi can also be interpreted as “central pole” or “pillar,” like the ridgepole of a house around which all the other parts are arranged and upon which they all depend. T’ai chi is a Western abbreviation of the Chinese term tai chi ch’uan, the full name of the Chinese fighting art, which translated means “fighting art based on the laws of the universe.”

CHANGE AND HARMONY

Chinese philosophy is based on a belief in two opposing but complementary forces, yin and yang. Traditionally, yin has been presented as the feminine force, passive, nurturing, and soft, and yang as the harder, more active masculine principle. Yin and yang are also the forces of harmony and change, and together they form a balanced whole. When they are not in perfect equilibrium, disorder and disease are said to follow. The interrelationship between change and harmony is the guiding principle behind tai chi, which seeks to establish a dynamic equilibrium between the two.

Change is a constant in our lives. The Earth moves unceasingly around its orbit, causing the seasons to change and recreating the cycle of birth, life, and death. From the moment of conception to the time of death the body changes ceaselessly. The blood circulates, air is breathed in and out, mind and body mature and age. Throughout our lives we experience not one moment of absolute stillness. Change brings about rhythm, however – every in-breath is followed by an out-breath – and so harmony is maintained.

This ceaseless interplay between change and harmony is perfectly expressed in the yin-yang symbol. As any condition reaches its fullest point, it already contains the seed of its opposite: in the dark portion is a seed of white; and in the white portion is a seed of black.

In tai chi the interplay between yin and yang, the forces of change and harmony, reveals itself in the changing postures and the quality of the movements. Body weight shifts from one leg to the other, awareness moves from inside to out, empty changes to full, open to closed. The forces work simultaneously, creating a continous and ever-changing dance of energy. Life is filled with countless forces and arrangements of opposites: day and night; sound and silence; giving and receiving; fear and courage; sadness and happiness. Taoism teaches that the concepts of yin and yang offer a view of the way things work according to a natural law of change and harmony.

Everyone practicing tai chi is enjoined to embody natural law in their movements in accordance with the constantly changing balance between yin and yang. It may take time, practice, concentration, and self-love, but the reward is true harmony of body and mind, the achievement of central equilibrium – which is the essence of tai chi.

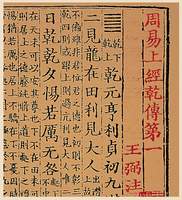

THE I CHING

The I Ching or Book of Changes is the classic of Taoist thought. It is a book of divination and wisdom, stemming from oracles written more than 4,000 years ago. The I Ching is a collection of commentaries on 64 hexagrams. Hexagrams are drawn by tossing coins. You ask the book a question on any subject, and its answer appears in the hexagram you drew. The text interprets life conditions and situations in terms of yin and yang. Many people find the I Ching assists in their decisions by helping them to make wise choices.

The hexagram Chien from a copy of the I Ching printed in China in the tenth century B.C.E.

YIN YANG QUALITIES

Below is a list of a few of the many yin and yang qualities. It is important, however, not to see any of them as always being a yin or a yang quality, but as generally belonging to either category under certain circumstances. For example, the Earth receives the seed, protects it, and nurtures it, and so is usually categorized as yin, but if you fall and hit the ground you experience it as hard – as yang.

Yin Yang Inward Outward Smooth Rough Holding Sending Receiving Giving Listening Speaking Dark Light Earth Sky Soft Hard No boundaries Clear boundariesThe Birth of Tai Chi

ONE TRADITION SAYS that tai chi originated some 5,000 years ago during the reign of China’s mythical first emperor, Fu Hsi. Exercises for health are described in a collection of classic writings attributed to one of his successors, the legendary Yellow Emperor, Huang Ti, who is said to have founded the traditional Chinese system of medicine. The principles of the art were established by Taoist recluses who retired from the world to live as hermits. And it evolved during turbulent periods in China’s history as a martial art called t’ai chi ch’uan.

Although tai chi is thought to have originated before the first millennium, the earliest known references date from the T’ang Dynasty (618–960 C.E.). They describe “patterns” of tai chi practiced by recluses who had retired to China’s mountain regions.

The early tai chi teachers remain semi-mythical figures. Chang San-feng is no exception, a colorful figure, said to have been more than 6 feet tall and a powerful fighter. No one knows whether he really existed or when he lived. Yet, he is credited as the founder of a spiritual fighting art called Wudang kung fu.

Three founding fathers of Taoism, the ancient Chinese philosophy on which tai chi is based.

History records that Chang San-feng studied under a Taoist recluse living in the northwest of China, then studied martial arts at the Shaolin Temple Monastery near Zhengzhou in modern Henan.

It is said that in tai chi a process leads the player from body to mind to spirit, and eventually back to the Great Void to merge with the cosmos. Chang San-feng followed this path, which led him to further studies at the Purple Summit Temple on the Wudang Shan, a mountain held sacred by Taoists. Chang San-feng is said to have spent nine years there studying nature, and was struck by the martial potential of yielding while watching a fight between a snake and a bird. He modified his kung fu style, replacing many of the physical training methods with mind-focusing techniques such as visualization, and the cultivation of energy through qigung. From this point, China’s “soft” fighting arts – ba gua, hsingi, and t’ai chi ch’uan – developed.

As the peaceful and prosperous Ming Dynasty declined in the 1600s, to be replaced by conquerors from Manchuria, hand-to-hand battlefield combat was a frequent reality and personal combat skills were at a premium. Foremost among the soft, or internal, fighting styles was the Chen style of tai chi, founded by Chen Wang-t’ing, a soldier in the imperial Ming armies who served under a respected general, Ch’i Chiguang. Ch’i wrote the Classic of kung fu, setting out the principles of what became Chen style. However, it is also claimed that Chen studied under the author of the now-classic Treatise on T’ai Chi Ch’uan, Wang Tsung-yueh, whose lineage could be traced back to the legendary fighter Chang San-feng.

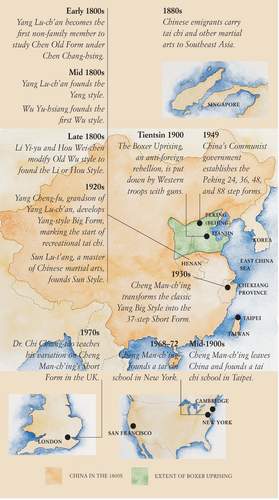

By the 1800s tai chi was at its zenith as a fighting art, and the Chen style was well established. However, it was still taught only to members of the Chen family. In the early 1800s a student from a poor family, Yang Lu-ch’an, worked in the household of the clan head, Chen Chang-xing. where he spied on tai chi sessions. One day he offered to fight a stranger who had challenged Chen Chang-xing. Yang fought so well that it was obvious that he had been secretly learning the Chen style. Chen accepted Yang as a student.

Yang Lu-ch’an traveled China as a Chen family representative, offering challenges to fighters, and was nicknamed “Ever-Victorious.” He is said to have been appointed to teach Chen-style t’ai chi ch’uan to the household of the Ch’ing Emperor. Chen style is dynamic and physically demanding. To adapt the style for courtiers who had not trained from early youth Yang omitted the more vigorous movements, creating a gentler form of tai chi. Today, while Chen is recognized as the oldest of the three main tai chi styles practiced today, a shorter version of Yang’s style is most widely taught.

An outstanding teacher who bridged the classic tai chi styles with 20th century development is Cheng Man-ching. In the 1930’s Cheng, a disciple of Yang Cheng Fu, condensed his teacher’s form of 108 moves down to a more managable 37. He opened a school in New York in the 1960’s and as a result was most instrumental in bringing tai chi to West. Another short version of the Yang style was created in 1949 by the Washu Council of China, known as the Peking 24 step.

The third style was developed by Yang’s student, Wu Yu-hsiang, who also studied with the Chen family, so his style incorporates features of both. These three styles have given rise to numerous derivatives.

TAI CHI SPREADS WORLDWIDE

During the 1800s t’ai chi ch’uan flourished and the classic schools were established. New warfare technology diminished tai chi’s role as a battlefield art so that the tai chi families no longer needed to keep their arts secret. Since 1900 tai chi has become accessible to ordinary Chinese people, and has spread westward, to North America, Australia and New Zealand, and into Europe.

A Healing Art

TAI CHI IS best known in the West as a system of exercises to benefit health, prevent degenerative illnesses, and promote longevity. It stimulates circulation, aligns misplaced bones, mobilizes the joints, stimulates and maintains vital organs, and improves balance and coordination. It improves the breathing, which revitalizes body and brain. But tai chi is a holistic practice and it also trains the mind to focus and concentrate. It widens sensitivity and the capacity to feel, so that people who practice become more awake, alive, and responsive.

A few minutes of gentle massage can release tension and remove pain.

The following pages show many different ways in which tai chi can benefit health of body and mind. Tai chi works with the body to support and encourage its natural capacity for healing. Practicing the techniques correctly raises chi, or life energy, which strengthens the immune system and improves health, and jin or whole body energy, also called intrinsic energy, which improves coordination.

Tai chi movements build energy gradually. Tai chi movements generate warmth, often accompanied by a sense of fullness. After perhaps half an hour of practice the body may feel as if it is humming. After a training session this can be felt as heat energy in certain parts of the body, especially the hands, which seem to radiate heat.

HEALING OTHERS

Massage for tai chi can be reassuring, so offering to massage relatives or friends is a way of helping them through touch. Explore the following methods for yourself and discover how the healing energy generated in tai chi practice can help you, your friends, and family.

Foot-holding and intuitive foot massage

The simple technique of foot-holding embodies the principle of “not doing” perfectly. For the best effect the person to be massaged should lie down comfortably, or, if this is not possible, sit in a chair with the knees and legs supported on a stool or cushions. Rest your hands on the other person’s ankles or feet and do nothing for at least 10 minutes. Notice how energy builds in both bodies. This demonstrates the two-way nature of healing and the positive feedback that begins with tai chi practice. Intuitive foot massage is stimulating and comforting. Simply massage the other person’s feet in any way that occurs to you.

Dispelling a headache

Ask your friend to sit comfortably. Rest your right hand on his or her forehead and your left hand on the back of the neck, and keep your hands still for at least three minutes. Now move your hands about 9 inches away from your friend’s head and neck, imagining them offering a healing space into which the “disease” of the headache can melt. Finish by placing both of your hands in light contact with your friend’s head for about a minute.