Полная версия:

The Wildlife-friendly Garden

Contents

Cover

Title Page

The Garden Habitat

Garden diversity

Wildlife-friendly gardens

Planning your garden

A wildlife meadow

The garden hedge

Wildlife walls

The garden pond

A log garden

Under your feet

The compost heap

Garden Mammals

Reading the signs

Hedgehogs

Rodents

Deer

Foxes

Badgers

Bats

Garden Birds

A beak for the job

Food for the birds

Plants for birds

Familiar garden birds

Identifying garden birds

Houses for birds

Dealing with casualties

Reptiles and Amphibians

Lizards

Snakes

Frogs, toads and newts

Insects and Other Invertebrates

Butterflies

Identifying butterflies

Garden moths

Identifying moths

Bees and wasps

Dragonflies

Ladybirds

Spiders

Keep Reading

Keeping a record

Useful information

Bibliography

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Michael Chinery

PART ONE

The Garden Habitat

All over the world, forests are being felled, wetlands are being drained, and heaths and grasslands are being ploughed up to make way for crops and houses. However, while these natural or semi-natural habitats are shrinking in the face of the increasing human population, one habitat – the garden – is increasing, and I think it is no exaggeration to say that today’s gardens are our most important nature reserves.

Gardens cover almost a million hectares of the United Kingdom alone, and it is this enormous extent, as well as their great variety, that makes them such valuable wildlife refuges. In some areas, gardens are undoubtedly more important for wildlife than the surrounding ‘countryside’, with its pesticide-drenched monocultures. This is true even where the gardener does nothing in particular to encourage visitors: the wide range of plants cultivated in a typical garden is itself enough to attract lots of insects, and the insects bring in the birds.

Wildlife gardening aims to increase the number of native species visiting and residing in the garden, but it need not entail any loss of productivity. By being more laid-back and a little less tidy, you can have a garden buzzing with wildlife and filled with tasty crops and fine flowers. Your guests will actually do much of the pest control for you – free of charge!

Garden diversity

Although I have referred to the garden as a single habitat, on a par with a woodland or a meadow, most gardens are really very complex mixtures of habitats, each supporting its own rich assemblage of plant and animal life.

Flower beds

The flower border, a major feature of most gardens, contains a wide range of plants that flower at different times and attract insects and other small creatures for much of the year. Caterpillars chew the leaves, bugs suck the sap, bees and butterflies feast on the nectar, and many other insects attack the fruits and seeds. Hidden from view, the roots also provide sustenance for wireworms, leatherjackets, slugs, millipedes and numerous other creepy-crawlies, while earthworms derive most of their nourishment from the decaying plant matter in the soil. All of these small creatures provide food for birds and small mammals, so even a very simple flower border is really a mixture of several micro-habitats.

Michael Chinery

Even the smallest of backyards can be a riot of colour, packed with flowers that act as filling stations for butterflies and many other insects.

Michael Chinery

Tiny mosses, seen here covered with pear-shaped spore capsules, erupt from the smallest cracks in walls and paths.

Vegetable plots

The vegetable plot has a similar diversity, although it does not have much in the way of nectar sources and, being subject to more disturbance as crops are planted and harvested, it tends to support a smaller variety of animal life in general.

Trees, shrubberies and hedges

These lend welcome shade and shelter to other parts of the garden and are micro-habitats in their own right, providing homes and hunting grounds for insects, spiders, birds and many other creatures.

Walls, fences and paths

CONSERVATION TIP

If you find a strange creature in your garden, don’t assume it is harmful. Before squashing it with your foot, try to find out what it is and what it does. You will probably find that it is harmless or even useful – and then you won’t need to squash it!

These provide yet more living space for both flora and fauna, a fact that is easily appreciated when you look at the number of spider webs that adorn the fences in the autumn. Even concrete paths can support wildlife, tiny mosses wedge themselves into cracks in the concrete, while ants often nest underneath the paths and benefit from the heat absorbed by the concrete on sunny days – although you might not know that they are there until they fly off on their marriage flights in the summer.

Garden ponds

A pond is one of the richest of all wildlife habitats, and garden ponds are, happily, becoming increasingly popular. Pond-watching can be great fun, and the garden pond can literally be a life-saver for frogs, toads and dragonflies, all of which are now suffering from the disappearance of so many farm ponds and other watery sites in the countryside.

Michael Chinery

Hit by the disappearance of so many farm and village ponds, many frogs find refuge in our garden ponds and mop up the slugs in return for the hospitality.

Go for variety

Not all of the visitors to your garden will be welcome guests, of course, but they will all add to the richness of the garden and the great majority will do no harm. They are just using your garden as a home. The more habitats you can create in your garden, the more guests you are likely to get, and the more diversity of wildlife. This can only be good for the wildlife population as a whole.

Michael Chinery

A single climbing rose can feed a huge number of insects, which, in turn, can provide food for numerous spiders and birds. The birds may also nest there, well protected from predators by the rose’s prickly stems.

Wildlife-friendly gardens

Gardening for wildlife involves creating an approximation to one or more natural habitats that will be acceptable to birds and other wild creatures. It does not mean, however, giving the whole garden over to nature. You can continue to grow all your favourite flowers and vegetables in a wildlife garden.

Although a large garden can obviously support more plant and animal life than a small one, size is not that important. Even a small garden can contain several valuable wildlife habitats, such as a hedge, a small spinney or shrubbery, a pond and a grassy bank. It is what you plant in your garden that matters. Cultivated varieties and exotic plants certainly have a role in adding colour and excitement to a garden, but to be really wildlife friendly you do need to grow a selection of native shrubs and other plants. These are the species on which our native insects have evolved, and if you provide food for the insects, then you will indirectly feed many of our garden birds as well.

Having created habitats for the insects and birds, you will need to minimize any disturbance. So be a little less enthusiastic with the lawn mower and the hedge trimmer. Does your lawn really need to look like a bowling green, and does it matter if the hedge is a bit rough around the edges? Don’t be tempted to dead-head all of your plants; this might encourage a longer flowering season but it does deprive birds and insects of food and shelter. Bare soil needs weeding, so cover your garden with as much vegetation as you can; this will keep down the weeds and also give the birds a happy hunting ground. You might well find that wildlife-friendly gardening is gardener friendly as well!

Michael Chinery

The rough grass at the base of the wall in no way detracts from the appearance of this well-managed wildlife garden.

Keep wildlife safe

Michael Chinery

The great green bush-cricket is a noisy inhabitant of the many undisturbed garden hedges and shrubberies that exist both on the European continent and in southern England.

Thousands of shrews and other small mammals die every year in carelessly abandoned bottles. Getting in to sample the dregs is easy, but climbing the smooth sides to get out again certainly is not. Drink cans are not quite so bad, but beetles and many other useful creatures regularly drown in them.

Michael Chinery

Let brambles scramble over your hedge. Insects will sip nectar from the flowers in summer and the birds, and you, will be able to enjoy the fruits later in the year.

CONSERVATION TIP

Don’t use peat in your garden. Our peat bogs have shrunk alarmingly over the last 100 years or so because of the demand for peat, and their wildlife has dwindled accordingly. Plenty of alternatives to peat are on the market now, and for hanging baskets there is ‘Supermoss’ – a sphagnum substitute made from recycled cloth and paper pulp.

A healthy garden

It took millions of years for nature to build up an equilibrium, in which each plant and animal species has its place and in which each helps to keep the rest under control. Nothing lives alone in nature, for every creature either eats or is eaten by one or more other creatures. We have destroyed much of this delicate balance, but it is still not too late to put the process into reverse.

WHAT GOOD ARE MOSQUITOES?

This question is commonly asked by many people who have been bitten by these insects. Mosquitoes don’t do us any good, of course, but, in common with all other living things, they form part of nature’s intricate web and have a role to play in nature’s economy. From the point of view of a hungry swallow or a stickleback, mosquitoes are actually quite good!

Restoring the balance

The key thing is to live and work with nature, steering it in the direction we want in our gardens instead of destroying it completely. If we can achieve an approximation to nature’s balance of predators and prey, then no one species will be able to multiply to such an extent that it becomes a nuisance. By creating some natural habitats in your garden you will inevitably attract their characteristic wildlife. Trees and shrubs, for example, attract birds; ponds are magnets for frogs and toads; and flower beds pull in many colourful insects. These guests will add considerable interest to your garden and will also do much to keep down the less desirable visitors – the pests. They will not eradicate the pests, but the amount of damage is likely to be minimal and you will be able to boast a healthy garden with a balanced ecology.

CJ Wild bird Foods/David White

Although few of these young spiders, just hatched from their eggs, will survive to become adults, undoubtedly they will eat a lot of insects before themselves falling prey to various enemies.

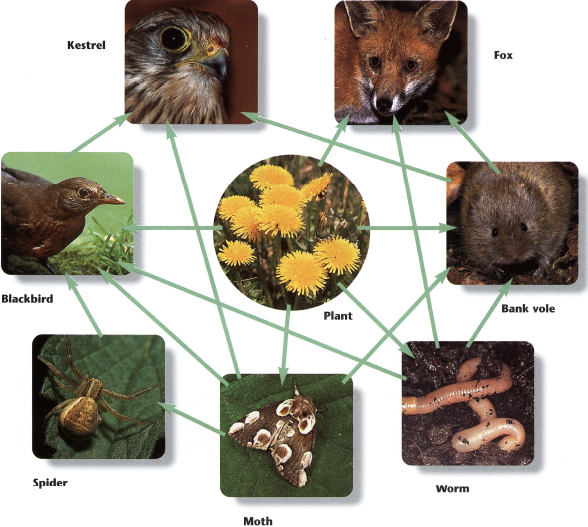

A TYPICAL GARDEN FOOD WEB

Michael Chinery

CJ Wild bird Foods/David White

Colin Varndell

Moth feeds on nectar; spider eats moth; blackbird eats spider. This is a typical food chain. Another example might be plant; insect; vole; fox. Many more such chains can be observed in the garden, and it quickly becomes obvious that these chains are all linked together in a web – because most animals eat more than one kind of food. Blackbirds, for example, are equally happy with earthworms and elderberries, while the bank vole may vary its normally vegetarian diet with snails and fungi as well as insects. Just a few of the chains in a garden food web are illustrated here, with the arrows pointing from the food to the consumers. You will find that each chain starts with a plant. With each species kept in check by its predators and/or food supplies, the whole community remains in a healthy equilibrium.

Garden friends and foes

Older nature books commonly listed the gardener’s friends and foes, but now that we know a lot more about the life histories of the animals and know that everything has its place in nature’s complex web, it is not so easy to pigeonhole them in this way. For example, a centipede eating a harmful slug might be regarded as a friend, but you might change your opinion on discovering that a centipede’s diet consists mainly of other centipedes. Nevertheless, it is still possible to recognize some positively useful creatures – friends – which should be welcomed into the garden and some without which our gardens would be better off. These are the pests that eat our crops and spread diseases and they must be discouraged if not actually destroyed.

FRIEND OR FOE?

This simple, although not infallible, rule of thumb may help you to decide which are the goodies and which are the not-so-good. Fast-moving garden creatures are generally predators and on your side, whereas slow-moving creatures tend to be herbivores and are thus often harmful in the garden.

Our friends

Michael Chinery

Long, sensitive antennae enable the ground beetle to track down its prey at night.

Michael Chinery

Lacewings often come to lighted windows at night; introduce them to your roses or other plants where they can eat the troublesome aphids.

Michael Chinery

A good friend in the garden, this hedgehog is busily polishing off a snail.

Our foes

Michael Chinery

Beautiful, but also beastly, the lily beetle must go if you value your lilies.

Michael Chinery

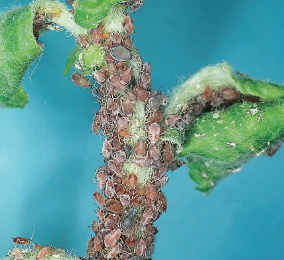

This apple shoot has been deformed by the piercing beaks of hundreds of sap-sucking aphids.

Michael Chinery