скачать книгу бесплатно

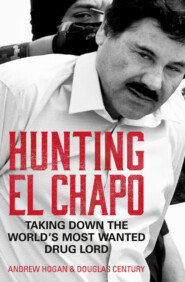

Hunting El Chapo: Taking down the world’s most-wanted drug-lord

Douglas Century

Andrew Hogan

This is the untold story of the American federal agent who captured the world’s most-wanted drug-lord.Every generation has its larger-than-life criminal legend living beyond the reach of the law: Billy the Kid, Al Capone, Ronnie Biggs, Pablo Escobar. But for every one of these criminals, there’s a Wyatt Earp, Pat Garrett or Slipper of the Yard. For Joaquín Archivaldo Guzmán-Loera a.k.a. ‘El Chapo’ – the 21st century’s most notorious criminal – that man is D.E.A. Special Agent Andrew Hogan.This is the incredible story of Hogan’s seven-year-long chase to capture El Chapo, a multibillionaire drug-lord and escape-artist posing as a Mexican Robin Hood, who in reality was a brutal sociopath responsible for the murders of thousands. His greedy campaign to take over his rivals’ territories resulted in an unprecedented war with a body count of over 100,000.We follow Hogan on his quest to achieve the seemingly impossible: to cross the border into Mexico and arrest El Chapo, the leader of the Sinaloa Cartel, a billionaire and Public Enemy No. 1, who had been evading capture for more than a decade and had earned a reputation for being utterly untouchable.This intimate thriller tells how Hogan single-mindedly and methodically climbed the ladder within the hierarchy of the Sinaloa Cartel – the world’s wealthiest and most powerful drug-trafficking organization – by creating one of the most sophisticated undercover operations in the history of the D.E.A. From infiltrating Chapo’s inner circle to leading a white-knuckle manhunt with an elite brigade of Mexican Marines, Hogan left no stone unturned in his hunt for the world’s most powerful drug kingpin.

ALSO BY DOUGLAS CENTURY

BARNEY ROSS

TAKEDOWN

STREET KINGDOM

ICE

IF NOT NOW, WHEN?

BROTHERHOOD OF WARRIORS

COPYRIGHT (#u8863867a-28f9-5e46-923f-f2b01bd261bc)

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in the US by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018 This UK edition published 2018

FIRST EDITION

© QQQ, LLC 2018

Cover layout design Dominic Forbes © HarperCollinsPublishers Cover photograph © AFP/Getty Images

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

The authors assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN 9780008245849

Ebook Edition © April 2018 ISBN: 9780008245863

Version 2018-07-18

AUTHORS’ NOTE (#u8863867a-28f9-5e46-923f-f2b01bd261bc)

This is a work of nonfiction: all the events depicted are true and the characters are real. The names of US law enforcement and prosecutors—as well as members of the Mexican military—have been altered, unless already in the public domain. For security reasons, several locations, makes of vehicles, surnames, and aliases have also changed. All dialogue has been rendered to the best of Andrew Hogan’s recollection.

To my wife and sons. —A.H.

Certainly there is no hunting like the hunting of man and those who have hunted armed men long enough and liked it, never really care for anything else thereafter.

— Ernest Hemingway, “On the Blue Water,” 1936

Contents

COVER (#u803ca355-63a5-5a5d-8273-898e0e2986ad)

TITLE PAGE (#ubd8ea9af-5fce-5d10-8808-ff5ebd8a4588)

COPYRIGHT (#ubaf14f9c-7ba2-52ef-85da-22f77d2d7abf)

AUTHOR'S NOTE (#u42f4d372-7cee-5d5c-b88a-5da8ae654a52)

PROLOGUE: (#u66e061e1-9dc6-56d2-a3d8-99c7de812829)

EL NIÑO DE LA TUNA (#u66e061e1-9dc6-56d2-a3d8-99c7de812829)

PART I (#u6cf9deea-8814-5b05-8ef0-19c4ed0a86a4)

BREAKOUT (#uff444126-2ef8-5e00-8216-9a20a72e3c8c)

THE NEW GENERATION (#uadcc42fe-63c8-583c-a6ca-273d044d038b)

EL CANAL (#u8ff2d30c-b93f-5968-8ffe-8947bcf75052)

TEAM AMERICA (#uc1d904e7-e965-594e-b4f8-45289728f41f)

PART II (#u014cd9d2-f530-5051-81ed-e7e684773f82)

LA FRONTERA (#u82e6679d-7ce0-5ac8-8c0d-b9049c7a9514)

DF (#u444c0be7-4916-59cb-967c-513fdd38717d)

BADGELESS (#ufa62620b-605a-5495-8a49-4654f535560c)

TOP-TIER (#uf521af3e-21a4-5079-ac3a-a72167e0dbc5)

ABRA LA PUERTA (#u64b362eb-fd1b-5bc7-b916-1e4225d3156a)

DUCK DYNASTY (#ub1db65b2-9970-57ff-9996-6cb6462401f3)

LOS HOYOS (#u04e91827-b061-502c-9c99-bb9c807d8b42)

PART III (#ue970e7a9-0b5a-50cd-a77c-721b3257d3f6)

LA PAZ (#u2692442d-7b57-5f22-a1af-bc28ca80edc2)

FOLLOW THE NOSE (#u2fbfed04-bf43-570d-8689-539eb0da6fe7)

LION’S DEN (#u0377fec7-2c7e-5883-b0c2-1f23ddbc8ba3)

THE DROP (#ud9b7c032-9f66-5718-bc0a-1280cf99635a)

SU CASA ES MI CASA (#u942a1223-9377-5755-af49-6ae5670a4dd3)

EL 19 (#ubf312bb3-dcd4-52d1-b860-9979960fc184)

MIRAMAR (#uf29e8693-efe0-5c88-a94f-30ebefd6ff6b)

THE MAN IN THE BLACK HAT (#uf2d4c9a1-490b-5df9-8c3c-7e01d3a4d090)

QUÉ SIGUE? (#u113ea2be-1eed-5894-85a8-a80f91e47a08)

EPILOGUE: (#u5b8d7ce5-0d06-5fac-a06f-96f1bac106e0)

SHADOWS (#u5b8d7ce5-0d06-5fac-a06f-96f1bac106e0)

PHOTOS (#u3cb195fc-285a-5e37-a3b8-b868129daade)

MAPS (#u00379489-79f8-5d86-b7d0-06d887acfb90)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (#u509519d6-fcff-532d-a383-37861e0c4c1e)

A NOTE ON SOURCES (#u2e85021d-fbca-5d70-a641-107a2dba1ff3)

GLOSSARY (#u2923b2ce-fb9b-5965-a380-0fac0f33ba5b)

INDEX (#u95eae84e-7672-5bd7-97e8-100e6429490b)

ABOUT THE AUTHORS (#ufcf5e975-cdfd-5998-a268-50119a591099)

NOTES (#u1cac1a38-c65d-5dac-90bb-12933ca51961)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#ua2f125a9-abba-55ec-ade1-02ef36c17cfb)

PROLOGUE: EL NIÑO DE LA TUNA (#u8863867a-28f9-5e46-923f-f2b01bd261bc)

PHOENIX, ARIZONA

May 30, 2009

I FIRST HEARD THE legend of Chapo Guzmán just after midnight inside Mariscos Navolato, a dimly lit Mexican joint on North 67th Avenue in the Maryvale section of West Phoenix. My partner in the DEA Narcotic Task Force, Diego Contreras, was shouting a translation of a song into my ear:

Cuando nació preguntó la partera Le dijo como le van a poner? Por apellido él será Guzmán Loera Y se llamará Joaquín

“When he was born, the midwife asked, ‘What are they gonna name the kid?’ ” Diego yelled, his breath hot and sharp with the shot of Don Julio he’d just downed. “The last name’s Guzmán Loera, and they’re gonna call him Joaquín . . .”

Diego and I had been working as partners in the Phoenix Task Force since early 2007, and two years later we were like brothers. I was the only white guy inside Mariscos Navolato that May night, and I could feel every set of eyes looking me up and down, but sitting shoulder to shoulder with Diego, I felt at ease.

Diego had introduced me to Mexican culture in Phoenix as soon as we met. We’d eat birria out of plastic bowls in the cozy kitchen of some señora’s home that doubled as a makeshift restaurant and order mango raspados from a vendor pushing a cart across the street, all while listening to every narcocorrido

Diego had in his CD collection. Though I clearly wasn’t from Mexico, Diego nevertheless told me I was slowly morphing into a güero—a light-skinned, blond-haired, blue-eyed Mexican—and soon no one would take me for a gringo.

The norteño was blaring—Los Jaguares de Culiacán, a fourpiece band on tour in the Southwest, straight from the violent capital of the state of Sinaloa. The polka-like oompa-loompa of the tuba and accordion held a strange and contagious allure. I had a passing knowledge of Spanish, but Diego was teaching me a whole new language: the slang of the barrios, of the narcos, of “war zones” like Ciudad Juárez, Tijuana, and Culiacán. What made these narcocorridos so badass, Diego explained, wasn’t the rollicking tuba, accordion, and guitar—it was the passionate storytelling and ruthless gunman attitude embodied in the lyrics.

A dark-haired waitress in skintight white jeans and heels brought us a bucket filled with cold bottles of La Cerveza del Pacifico. I grabbed one out of the ice and peeled back the damp corner of the canary-yellow label. Pacifico: the pride of Mazatlán. I laughed to myself: we were in the heart of West Phoenix, but it felt as if we’d somehow slipped over the border and eight hundred miles south to Sinaloa. The bar was swarming with traffickers—Diego and I estimated that three-quarters of the crowd was mixed up somehow in the cocaine-weed-and-meth trade.

The middle-aged traffickers were easy to spot in their cowboy hats and alligator boots—some also worked as legit cattle ranchers. Then there were narco juniors—the new generation—who looked like typical Arizona college kids in Lacoste shirts and designer jeans, though most were flashing watches no typical twenty-year old could afford.

Around the fringes of the dance floor, I spotted a few men who looked as if they’d taken a life, cartel enforcers with steel in their eyes. And scattered throughout the bar were dozens of honest, hardworking citizens—house painters, secretaries, landscapers, chefs, nurses—who simply loved the sound of these live drug balladeers from Sinaloa.

Diego and I had spent the entire day on a mind- numbing surveillance, and after ten hours without food, I quickly gulped down that first Pacifico, letting out a long exhale as I felt the beer hit the pit of my stomach.

“Mis hijos son mi alegría también mi tristeza,” Diego shouted, nearly busting my eardrum. “My sons are my joy—also my sadness. “Edgar, te voy a extrañar,” Diego sang, in unison with the Jaguares’ bandleader. “Edgar, I’m gonna miss you.”

I glanced at Diego, looking for an explanation.

“Edgar, one of Chapo’s kids, was gunned down in a parking lot in Culiacán,” Diego said. “He was the favorite son, the heir apparent. When Edgar was murdered, Chapo went ballistic. That pinche cabrón fucked up a lot of people...”

It was astonishing how Diego owned the room. Not with his size—he was no more than five foot five—but with his confidence and charm. I noticed one of the dancers flirting with him, even while she was whirling around with her cowboy-boot-wearing partner. Diego wasn’t a typical T-shirt-and-baggy-jeans narcotics cop—he’d often dress in a pressed collared shirt whether he was at home or working the streets.

Diego commanded respect immediately whenever he spoke—especially in Spanish. He was born on the outskirts of Mexico City, came to Tucson with his family when he was a kid, and then moved to Phoenix and became a patrolman with the Mesa Police Department in 2001. Like me, he earned a reputation for being an aggressive street cop. Diego was so skilled at conducting drug investigations that he’d been promoted to detective in 2006. One year later, he was hand-selected by his chief for an elite assignment to the DEA Phoenix Narcotic Task Force Team 3. And that was when I met him.

From the moment Diego and I partnered up, it was clear that our strengths complemented one another. Diego had an innate street sense. He was always working someone: a confidential informant, a crook—even his friends. He often juggled four cell phones at a time. The undercover role—front and center, doing all the talking—was where Diego thrived. While I loved working the street, I’d always find myself in the shadows, as I was that night, sitting at our table, taking mental note of every detail, studying and memorizing every face. I didn’t want the spotlight; my work behind the scenes would speak for itself.

Diego and I had just started targeting a Phoenix-based crew of narco juniors suspected of distributing Sinaloa Cartel cocaine, meth, and large shipments of cajeta—high-grade Mexican marijuana—by the tractor-trailer-load throughout the Southwest.

Though we weren’t planning to engage the targets that night, Diego was dressed just like a narco junior, in a black Calvin Klein button-down shirt, untucked over midnight-blue jeans, and a black-faced Movado watch and black leather Puma sneakers. I looked more like a college kid from California, in my black Hurley ball cap, plain gray T-shirt, and matching Diesel shoes.

My sons are my joy and my sadness, I repeated to myself silently. This most popular of the current narcocorridos—Roberto Tapia’s “El Niño de La Tuna”—packed a lot of emotional punch in its lyrics. I could see the passion in the eyes of the crowd, singing along word for word. It seemed to me that they viewed El Chapo as some mix of Robin Hood and Al Capone.

I looked over and nodded at Diego as if I understood fully, but I really had no clue yet.

I was a young special agent from Kansas who’d grown up on a red-meat diet of Metallica, Tim McGraw, and George Strait, and it was a lot to take in that first night with Diego in Mariscos Navolato.

Up on the five flat-screen TVs, a big Mexican Primera División soccer match was on—Mérida was up 1–0 against Querétaro, apparently, though it meant little to me. The CD jukebox was filled with banda and ranchera, the walls covered in posters for Modelo, Tecate, Dos Equis, and Pacifico, homemade flan, upcoming norteño concerts, and handwritten signs about the mariscos specialties like almeja Reyna, a favorite clam dish from Sinaloa.

“El Chapo”? Was “Shorty” supposed to be a menacing-sounding nickname? How could some semiliterate kid from the tiny town of La Tuna, in the mountains of the Sierra Madre—who’d supported his family by selling oranges on the street—now be celebrated as the most famous drug lord of all time? Was Chapo really—as the urban legends and corridos had it—even more powerful than the president of Mexico?

Whatever the truth of El Chapo, I kept my eyes glued to the narco juniors sitting at a table near the far end of the bar. One had a fresh military-style haircut, two others fauxhawks, the fourth sporting an Arizona State University ball cap. Diego and I knew they were likely armed.

If the narco juniors went out to their cars, we’d have to follow.

Diego tossed two $20 bills on the table, winked at the waitress, and rose from his seat. Now the crew shifted in their seats, one getting to his feet, fixing the brim on his cap, pivoting on the sole of his Air Jordans like a point-guard.