скачать книгу бесплатно

‘Clear.’

Sandra was halfway up the stairs, listening to her heart and every creak from the bare boards. The torch was slick in her hand.

‘Hello? Anyone here?’

The thunder of police boots on the steps behind her drowned out any sounds she might have heard. Bathroom: filthy in the jumping light from her torch, but no one hiding. A bedroom, piled high with rubbish and dirty clothes. No bed, but there was a pile of blankets on the floor, like a nest. A second bedroom was at the front of the house. It was marginally tidier than the other one, mainly because there was almost no furniture in it apart from a mattress on the floor. Shoes were lined up neatly in one corner and a collection of toiletries stood in another.

The woman was lying across the mattress, half hanging off the edge, a filthy blanket draped across her. Her head was thrown back. Dead, Sandra thought hopelessly, and made herself smile at the small boy who crouched beside the body.

‘Hello, you. We’re the police. Are you all right?’

He was small and dark, his hair hanging over his eyes. He blinked in the light, his eyes darting from her to the officer behind her. He wasn’t crying, and that was somehow worse than if he’d been sobbing. Sandra was bad at guessing children’s ages but she thought he could be eight or nine.

‘What’s your name?’

Instead of answering he huddled closer to the woman. He had pulled one bruised arm so it went around him. It reminded Sandra of an orphaned monkey clinging to a cuddly toy.

‘Can I come a bit closer? I need to check if this lady is all right.’

No reaction. He was staring past her at the officer behind her. She waved a hand behind her back. Give me some room.

‘Is this your mummy?’ she whispered.

A nod.

‘Is your daddy here?’

He mouthed a word. No. That was good news, Sandra thought.

‘Was he here earlier?’

Another nod.

Sandra inched forward. ‘Did you put that blanket over your mummy?’

‘Keep her warm.’ His voice was hoarse.

‘Good lad. Good idea. And you put something under her head.’

‘Coat.’

‘Brilliant. Can I just check to see if she’s all right?’ Sandra stretched out a gloved hand and touched the woman’s ankle. Her skin was blue in the light of the torch, and even through the latex her skin felt cold.

‘He hurt her.’

‘Who did, darling? Your dad?’

The boy blinked at her. After a long moment, he shook his head slowly, definitely. It would be someone else’s job to find out who had done it, Sandra thought, and was glad it wasn’t her responsibility. The closer she got to the woman on the mattress, the more she could see the damage he’d done to her. And the boy had watched the whole thing, she thought.

‘All right. We’ll help her, shall we?’

His huge, serious eyes were fixed on Sandra’s. She wasn’t usually sentimental, but a sob swelled up from deep in her chest and burst out of her mouth before she could stop it. She held out her arms. ‘Come here, little one.’

He shrank into himself, turning away from her towards his mother. Too much, too soon. She bit her lip. The sound of low voices came from the hall: the paramedics at long last.

‘I’m sorry, but you can’t stay here. We’ve got an ambulance for your mummy. We need to let the ambulance men look after her.’

‘I want to stay. I want to help.’

‘But you can’t.’

The boy gave a long, hostile hiss, a sound that made Sandra catch her breath. The paramedics crashed into the room, carrying their equipment, and shoved her out of the way. She leaned against the wall as they bent over the figure on the mattress. It was as if Sandra had come down with a sudden, terrible illness: her stomach churned and there was a foul taste in her mouth. A cramp caught at her guts but she couldn’t go, not in the filthy bathroom, not in what was going to be a crime scene. She clenched her teeth and prayed, and eventually the pain slackened. A greasy film of sweat coated her limbs. She lifted a hand to her head and let it fall again. What was wrong with her?

The boy had scrambled back when the paramedics crashed into the room. He crouched in the corner of the room among the shoes, those round solemn eyes taking everything in. Sandra watched him watching the men work on his mother’s body, and she shivered without knowing why.

2 (#u28ee208f-6cba-5ad7-aa6c-e4e06d661814)

It was a day like any other; it was a day like they all were inside. Time pulled that trick of dragging and passing too quickly and all that happened was that he was a day further into forever.

He sat on his own, in silence, because he’d been allocated a cell to himself. It was for his protection and because no one wanted to share with him. He wasn’t the only murderer on the wing – far from it – but he was notorious, all the same.

That wasn’t why no one wanted to share with him. His health wasn’t good, a cough rattling in his chest all night long. That was more of a problem than the killing, he thought. But he’d taken his share of abuse for the murders, all the same. No one liked his kind.

He shifted his weight in the cheap wooden-framed armchair, feeling it creak under him. He had never been a fat man but prison had pared away at his flesh, carving out the shadow of his bones on his face.

The room was fitted out like a cheap hostel – a rickety wardrobe, a small single bed, a desk against the wall. There were limp, yellow curtains at the window. At a glance you might not notice the bars across the same window, or the stainless steel sink, or the toilet that was behind a low partition. That was one good thing about being on his own. He’d shared cells before, when he was younger. You never got used to the smell of another man’s shit. Of all the smells in the prison – and there were many – that was the worst.

He picked up the envelope that he’d left lying on his desk. It was open. A screw would have read it before he ever saw it. That was standard. Small writing, black ink. He wasn’t used to seeing it: his name in that writing. He turned it over a couple of times. Nothing important in it or he’d never have seen it. But no one writes a letter without saying something, even if they don’t mean to say anything at all.

He ripped the envelope getting the letter out of it. The paper was flimsy, the words on the other side bleeding through. He wasn’t a great reader at the best of times. His eyes tracked down the centre of the page, the scrawl transforming itself into phrases here and there. Don’t forget we’re all trying … I know you can … easy for me to say … coming to see you … your appeal … lose heart … forget what happened … start again … have hope … your son.

‘Fuck you.’ It was a whisper, inaudible above the banging and shouting and echoing madness of a prison in the daytime. With a wince, he got to his feet and crossed to the toilet. He stood over it, tearing the letter in half and half again, ripping the paper until it was a handful of confetti. He dropped it into the bowl. He’d imagined the ink would run but it didn’t. The paper sat on the surface of the water, the black writing burning itself onto his retinas. He pissed on it in a stop-start trickling stream, annoyed by that as much as the way the paper stuck damply to the sides of the toilet. He flushed, and waited, and grimaced at the scattered, dancing fragments that remained in the water.

He had a whole life sentence stretching ahead of him but that wasn’t what made him bitter.

If by some miracle he got out, he would never be free.

3 (#u28ee208f-6cba-5ad7-aa6c-e4e06d661814)

The lift doors closed and I shut my eyes, then forced them open again. It took about half a minute to go from the ground floor to our office: thirty seconds wasn’t quite long enough for a cat nap, even for me. The weight of the box I was carrying pulled at the muscles in my shoulders and arms but that was fine; it distracted me from the wholly unpleasant sensation of mud-soaked boots and trouser legs. I didn’t need to glance in the lift’s mirror to see how bedraggled I was after a long night and a cold morning at a crime scene in a bleak, muddy yard. I only had to look to my left, where Detective Constable Georgia Shaw was hunched inside a coat that was as saturated as mine. Her usually immaculate fair hair hung around her face in tails. Like me, she was holding a heavy cardboard box filled with evidence bags and notes.

‘We drop this stuff off. We do our paperwork.’ I paused to cough: the chill of the night had sunk into my chest. ‘We finish up and we go home.’

Georgia nodded, not looking at me.

‘Nothing else. Home, hot baths, clean clothes, get some sleep.’

Another nod.

‘If anyone manages to track down Mick Forbes and he gets arrested we’ll have to come back to interview him.’ Mick Forbes, a scaffolder in his fifties, the chief and only suspect in the murder of his best friend, Sammy Clarke, who had been battered to death in the muddy yard where we’d spent the night.

Georgia sniffed.

‘So get some rest while you can.’

‘OK.’ Her voice was a whisper.

The lift doors opened and I strode out, trying to look as if it was normal for my feet to squelch as I walked through the double-doors into the office. Head high, Maeve.

A quick scan of the room was reassuring: a handful of colleagues, mostly concentrating on their work or on the phone. A few raised eyebrows greeted me. An actual laugh came from Liv Bowen, my best friend on the murder investigation team, who bit her lip and dragged her face into a serious expression when I glowered at her. But for a brief moment, I allowed myself to feel relieved. I’d got away with it this time. I’d rush through the paperwork and then escape, unseen by—

DCI Una Burt opened the door of her office. ‘Maeve? In here. Now.’

I stopped, caught in the no man’s land between her door and my desk. Common sense dictated I should put the box down rather than carrying it into her office, but that meant leaving my evidence unattended. ‘Ma’am, I’ll be with you in a minute—’

‘Right now.’ The edge in her voice was serrated with irritation and something more unsettling. The box could come with me, I decided, and trudged through the desks to Burt’s office.

My first impression was that it was full of people. My second was that I would rather have been just about anywhere else at that moment, for a number of reasons. The pathologist Dr Early sat in a chair by the desk, tapping her fingers on a cardboard folder that was on her knee. She was young and thin and intense, rarely smiling – which I suppose wasn’t all that surprising, given her job. Today she looked grimmer than usual. Standing beside her, to my complete surprise, was a man who was tall, silver-haired and catch-your-breath handsome. My actual boss, although he was currently supposed to be on leave: Superintendent Charles Godley.

‘Sir.’

‘Maeve.’ He smiled at me with genuine warmth as I put the box down at my feet. ‘You look as if you had an interesting night.’

‘Not the first time she’s heard that. But I’ll give you this, Kerrigan, you don’t usually look as if you spent the night in a sewer.’ The inevitable drawl came from the windowsill where a dark-suited man lounged, his arms folded, his legs stretched out in front of him so they took up most of the room. Detective Inspector Josh Derwent, the very person I had been hoping to avoid. I could feel his eyes on me but I wouldn’t give him the satisfaction of reacting. Instead I smiled back at Godley.

‘It wasn’t the most pleasant crime scene, but I’ll live. It’s good to see you, sir.’

‘You too.’

‘Are you coming back to us?’ I had sounded over-enthusiastic, I thought, and felt the heat rising to my face. Una Burt wouldn’t like it if I was too keen to see Godley return. She had only been a caretaker, though, standing in for him while he was away on leave.

‘Not quite. Not yet.’ The smile faded from his face. ‘I’m here for another reason. I’ve got a job for you.’

‘For me?’

‘For you and Josh.’ Una bustled around to sit behind her desk, pausing until Derwent moved his feet out of her way. She sat down, pulling her chair in and leaning her elbows on the desk – the desk she had inherited from Godley. He was much too polite to react, although I knew he would have recognised it as her marking her territory. Currently, he was a visitor in her office and she wanted him to know it.

‘What sort of job?’ I asked, wary.

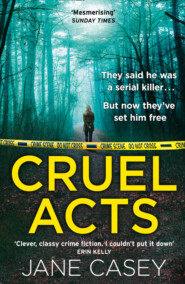

‘Leo Stone,’ Godley said. ‘Our latest miscarriage of justice.’

I frowned, trying to place the name. ‘I don’t think I know—’

‘Yeah, you do.’ Derwent’s voice was soft. ‘The White Knight.’

That sounded more familiar to me. Before I’d run the reference to earth, though, Godley snapped, ‘I don’t like that name. I don’t like glamorising murder. We’re not tabloid journalists so there’s no need to use their language.’

Derwent shrugged, not noticeably abashed. Before he could say something unforgivable and career-threatening, I spoke up.

‘You said a miscarriage of justice.’ I didn’t know why I was distracting Godley from Derwent. If the situation were reversed he would sit back and enjoy my discomfort. ‘What’s happened?’

‘He was convicted last year, in October. He’s been in prison for thirteen months now. One of the jurors in his trial has spent that time writing a book about the experience, and self-published it without running it past a lawyer. In it, he happens to mention how he and another juror looked up Stone on the internet, against the judge’s specific instructions, during the trial.’ Anger made Godley’s voice clipped, the words snapped off at the end. ‘They discovered Stone’s previous convictions for violence and told all the other jurors about it.’

‘I think my favourite line is, “We left the court to discuss the evidence we’d heard, but it was just a pretence. We had already decided he was guilty, because of what we’d found out for ourselves.”’ Burt leaned back in her chair. ‘Exactly what you don’t want a jury to say. But instead of making his fortune selling his book, he’s earned himself a two-month sentence for contempt of court.’

‘So Stone’s appealing.’ It wasn’t a question: there wasn’t a defence lawyer in the world who would let an opportunity like that slip through their fingers.

‘He is. At the end of this week. And the appeal will be granted,’ Godley said.

‘Right.’ Lack of sleep was making my head feel woolly. ‘Well, there’ll be a retrial. The problem was with the jury, not the evidence.’

‘There should be a retrial. But that’s the issue I have.’ Godley looked at me, his eyes even bluer than I’d remembered. ‘What do you know about the case?’

‘A little. Not much more than I read in the papers.’ I tried to remember the details I’d gleaned. ‘They called him the White Knight because he seemed to be rescuing his victims. He kidnapped them and killed them, either immediately or later. By the time we found the bodies they were too decomposed to tell us much about what he’d done.’

He nodded. ‘We only found two bodies but we’re fairly sure there’s at least one more victim. I wouldn’t be surprised if there were more out there. He was a nasty piece of work. He was abusive in his relationships, he had convictions for fraud, burglary and theft, and he had a lengthy history of violence towards strangers, as the jury found out.’

‘When is he supposed to have started killing?’ I asked.

‘He got out of prison three years ago after serving five years for burglary. The first murder was a month later – a woman named Sara Grey. It was opportunist. Impulsive. I don’t believe he planned it particularly well but it worked so he tried it again.’ Godley folded his arms. ‘Don’t be misled by the nickname. He was a murderer, plain and simple, but they had to try and make him into something more exciting. They twisted the facts because they wanted to sell newspapers, not because it was true. He saw his opportunity to kidnap women and he took advantage of that. Three women disappeared in similar circumstances, but he was only charged with killing Sara Grey and Willa Howard. And he was convicted.’

‘OK.’ I was trying to read Godley’s expression. ‘But why does that involve us? It was Paul Whitlock’s team who investigated the killings, wasn’t it?’

‘It was, and he did a good job. But Glen Hanshaw was the pathologist who did the post-mortems.’

‘Oh.’ I didn’t need to say any more. I understood the problem now. Glen Hanshaw had been a good friend of Godley’s. He had clung on to his job despite the ravages of cancer, right up to the end. I was starting to see why Godley was so upset.

‘There have been two acquittals in murder trials since he died, largely because he wasn’t there to defend his findings.’

‘And because his findings were shaky,’ Dr Early said. She glanced up at Godley, her face set. ‘He was a fine pathologist but he started making mistakes in the months before he died and he wouldn’t accept that his judgement was impaired.’

‘The pain medication affected him,’ Godley said. ‘He wanted to work – it was the only thing that mattered to him. But he needed to be dosed up to be able to do the job.’

‘He should have known better than to persevere. It was self-indulgent.’ It was professionalism that made Dr Early sound so severe. I knew she had done her utmost to help and support Dr Hanshaw, and that she had mourned him as a mentor, if not a friend. Glen Hanshaw had been a short-tempered misogynist and I’d never really understood Godley’s fondness for him.

Now the superintendent sighed. ‘Whether he should have been working or not, he’s become a target for defence lawyers. If he was involved in a case, you can expect the evidence he gathered to be challenged. And in the case of Leo Stone, the defence team are going to be looking for anything they can throw at the new jury to distract them from Stone’s guilt.’

‘The trouble with retrials,’ Derwent said, ‘is that they’ve heard all the best lines already. If you go back with exactly the same case and run it the same way, the defence know what to expect.’

‘Which is where you come in,’ Godley said. ‘I want to put a stop to the attacks on Glen’s reputation and his work. Dr Early has agreed to review his cases going back to before his diagnosis, and specifically his work on Leo Stone’s prosecution. In the meantime, I don’t want any cases to collapse purely because of his involvement. His reputation matters, and not just because he’s not here to defend himself. If all his decision-making is called into question we are going to see a torrent of appeals, especially from prisoners with whole-life tariffs.’

‘The worst of the worst,’ Una Burt said. ‘And they have nothing better to do than look for grounds to appeal. They’re in for life; they don’t have anything to lose.’

Godley turned to me. ‘Maeve, I want you and Josh to look at the case against Stone. Start from scratch: witnesses, families, the works. I’ll arrange a meeting with Paul Whitlock.’

‘He’s going to be pleased,’ Derwent observed. ‘Nothing like having another team come and take over your case.’

‘He’ll be professional about it,’ Godley said sharply. ‘He’ll understand why I don’t want to take any chances. Whitlock’s priority, and mine, is making sure that the right man is in prison for the murders of Sara Grey and Willa Howard. If that man is Leo Stone, I want him off the streets and behind bars.’