Полная версия:

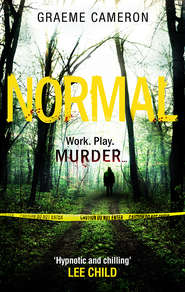

Normal: The Most Original Thriller Of The Year

“The truth is I hurt people. It’s what I do. It’s all I do. It’s all I’ve ever done.”

He lives in your community, in a nice house with a well-tended garden. He shops in your grocery store, bumping shoulders with you and apologizing with a smile. He drives beside you on the highway, politely waving you into the lane ahead of him.

What you don’t know is that he has an elaborate cage built into a secret basement under his garage. And the food that he’s carefully shopping for is to feed a young woman he’s holding there against her will—one in a string of many, unaware of the fate that awaits her.

This is how it’s been for a long time. It’s normal…and it works. Perfectly.

Then he meets the checkout girl from the 24-hour grocery. And now the plan, the hunts, the room…the others. He doesn’t need any of them anymore. He needs only her. But just as he decides to go straight, the police start to close in. He might be able to cover his tracks, except for one small problem—he still has someone trapped in his garage.

Discovering his humanity couldn’t have come at a worse time.

Graeme Cameron

For Oscar, Lewis, Sophie, Eve and Tracie

and

To Jamie Mason, for everything.

Contents

Cover

Back Cover Text

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Acknowledgments

A Conversation with Graeme Cameron

End Pages

Copyright

CHAPTER ONE

I’d learned some interesting things about Sarah. She was eighteen years old and had finished school back in July with grade-A passes in biology, chemistry, physics and English. Her certificate stood in a plain silver frame on a corner table in the living room, alongside her acceptance letter from Oxford University. She was expected to attend St John’s College in the coming September to commence her degree in experimental psychology. She was currently taking a year out, doing voluntary work for the Dogs Trust.

In her spare time, Sarah enjoyed drawing celebrity caricatures, playing with the Wensum volleyball team and collecting teddy bears. She was also an avid reader of fantasy novels and was currently bookmarking chapter 2, part 8 of Clive Barker’s Weaveworld. She’d been seeing a boy named Paul, though she considered him a giant wanker. He refused to separate from “almighty slut” Hannah, who was evidently endowed with a well-developed bosom and a high gag threshold. This caused Sarah considerable consternation, but she could not confide in her mother because “she wouldn’t understand” and would “just freak out again like last time.” She instead turned to her friend Erica, who was a year or two older and thus possessed of worldliness and abundant wisdom. Erica’s advice, apparently in line with her general problem-solving ethos, was to “cut off his dick and feed it to him.” Sarah didn’t talk to her mother about Erica, either.

All four walls of Sarah’s bedroom were painted a delicate shade of lilac, through which traces of old, patterned wallpaper were still visible. She had a single bed with a plain white buttoned cotton cover. She also had a habit of leaving clothes and wet towels on the floor. Her stuffed animals commanded every available inch of shelf and dresser space. The collection consisted of plush bears manufactured in the traditional method, and all had tags intact. It was too vast to waste time counting. But there were sixty-seven.

That morning, Sarah had spent just under half an hour in the bath and just over five minutes cleaning her teeth. She had no fillings or cavities, but the enamel on her upper front teeth was wearing thin from overbrushing. She also applied toothpaste to the index and middle finger of her left hand in a vain attempt at stain removal. There were no ashtrays in the house, and her cigarettes and lighter were hidden inside a balled-up pair of tights in the middle drawer of her dresser.

The following day was Sarah’s birthday. Many cards had already arrived and stood in a uniform row on the living-room mantelpiece. Someone had tidied in there early in the morning, but there was already an empty mug and a heat magazine on the coffee table. Sarah had a habit of leaving the TV on, whether she was watching it or not.

I’d discovered, too, that she plucked her bikini line. Most of her clothes were green. She dreamed of visiting Australia. She had a license but no car. The last DVD she watched was Buffy The Vampire Slayer—the feature film, not the more popular television series—and coincidentally, or rather perhaps not, Buffy was also the name of her cat.

Oh, and I knew three more things. I knew that her last hot meal was lasagna, her cause of death was a ruptured aorta and her tongue tasted of sugar and spice.

* * *

Fortunately, the kitchen floor was laid with terracotta tiles, and I easily located the cleaning cupboard, which held a mop and bucket, bleach, cloths, a roll of black bin liners and numerous antibacterial sprays. I hadn’t planned on doing this here, since I had a thousand and one other things to do and not enough time to do them, so my accidental severing of the artery was inconvenient, to say the least. Happily, I’d reacted quickly to deflect most of the blood and keep it off the walls.

I’d used a fourteen-inch hacksaw to remove the limbs, halving each one for portability. The arms and lower legs fitted easily inside a bin bag with the head and the hair lost in the struggle to escape. Using a separate bag for the buttocks and thighs, I’d placed these parts by the back door, away from the puddle of blood. The torso was unusually heavy despite Sarah’s small frame, and required a heavy-duty rubble sack to prevent tearing and seepage. Thoughtfully, I’d brought one with me.

The cleaning operation was relatively easy. My clothes went into a carrier bag, and I washed my face over the sink. Warm water followed by Dettol spray was adequate for removing the spatter from the cupboard doors and for disinfecting the worktops and the dining table once I’d swiped most of the blood onto the floor. Mopping the floor took three buckets of diluted bleach, which went down the drain in the backyard. The waste disposal in the sink dealt with stray slivers of flesh; the basin was stainless steel and simply needed a cursory wipe afterward.

The only concern was a couple of small nicks in the breakfast table, courtesy of my clumsiness with the carving knife. One or two spots of blood had worked their way into the wood, but these were barely visible and since the table was far from new, it was unlikely they’d be noticed by chance. Altogether, you’d never have known I was there.

In fact, the only thing out of place, once I’d moved the bin bags to the yard and returned each of Mum’s implements to its rightful home, was me. Fortunately, Sarah’s father was about my size, and I’d already dug out a pair of fawn slacks and an old olive fleece from the back of his wardrobe. The fleece was frayed at the elbows and smelled a little musty, but more importantly it was dry and unstained.

Satisfied, I slipped into my jacket and shoes, stepped outside and closed the door gently behind me.

In keeping with modern town-planning philosophy, the Abbotts’ house was separated from those to either side by the width of the garden path. In a token effort at providing some privacy from the neighbors, each garden had been bordered on both sides with high, oppressive panel fencing, secured at the bottom of the plot to a common brick wall. This wall was a good six inches taller than I was and, mindful of the difficulty in bundling Sarah over unseen, I elected to fetch the van and come back for her.

I took a lengthy run-up and hauled myself over, dropping down onto a carpet of twigs and soft brown leaves. The tree line was a matter of feet from the edge of the plot, at the foot of a steep incline. It was from here that I’d seen the upstairs window mist over and heard the bath running, watched Sarah in silhouette pulling off her clothes, waited until she closed the door and her ears were full of the roar of running water before I let myself in.

It was an altogether different scene now, as I picked my way back between the rows of pines toward the road. All that had made the dawn so perfect was gone—the dusting of snow on the rooftops, the faint crackling of twigs under muntjac hooves, the rustling of leaves disturbed by inquisitive foxes. In their place, the clatter of diesel engines and the grating thrum of cement mixers, the white noise of breakfast radio and the tap-tap-tap of trowel on brick. It had started soon after my arrival and, whilst the development would be blissfully quiet and neighborly once complete, for now the inescapable din of suburban sprawl rendered it a living hell. Although, on the other hand, it had at least allowed me the luxury of not having to tiptoe.

Thinking about it, there was something else missing, too—something I couldn’t quite put my finger on. Some weighty comfort I was accustomed to feeling against my leg as I walked, and which just wasn’t there anymore.

It wasn’t until I reached the van that I realized I’d locked the bastard keys in it.

* * *

I was loath to break a window, but the Transit was fitted with reinforced double deadlocks, and I specified the optional full-perimeter alarm system when ordering. Consequently, just as anyone else would have trouble breaking in, so did I. Having weighed up this option, considering my various time constraints against that of taking a cab home for the spare key, it didn’t take me long to find a brick. I was back in business, albeit at the mercy of the heater.

I’d left Sarah just behind the side gate, and I backed right up onto the two-car driveway to minimize my exposure. I took a moment to double-check the small toilet window at the back of the house; I’d chipped some of the paint away, and there were obvious indentations in the wood, but it was shut, and the glass was intact. Judging by the number of boxes and blankets piled up inside, and the concentration of long-abandoned cobwebs, the damage wouldn’t be discovered this side of summer. Good.

I was happy to find that Sarah hadn’t leaked out of any of the bags, and it took seconds to load the lighter ones into the van. But as I turned to collect the rubble sack, I happened to glance toward the doorstep, and my heart dropped. The face staring inquisitively back at me was a familiar one; I’d studied it briefly, in a tiny photograph from one of those instant booths you find in malls, fallen from Sarah’s diary as I lay on her bed. But it was unmistakable.

Erica’s hesitation was such that I could almost hear the whirring of her brain as she stood there, finger poised over the doorbell, eyebrows cocked, mouth agape. I knew all too well where her train of thought was carrying her, and so diverted it with a smile and a friendly wave.

“Hello, there,” I called. “Don’t panic, I’m not a burglar.”

Her expression turned instantly to one of apology. “Oh, no, no, I wasn’t thinking that.” She laughed, letting a few ringlets fall down to hide her eyes.

“Age Concern,” I explained. “Just collecting some old bags.” Ha ha. “I mean bags of old clothes. Are you looking for the young lady?”

She was walking toward me now. Dark curls bouncing, woollen scarf swaying to the rhythm of her hips. Breasts struggling to work the top button of her jacket loose with each confident stride. The blood began to race through my veins, the noise of the mechanical diggers and pneumatic drills fading to a low hum. “Yeah, do you know where she is? She’s not answering the door.” Close enough now that I could hear the rub of the denim between her thighs. I could take this one of two ways, probably avoid a scene by way of swift, decisive action, but as so often happens in the face of outstanding natural beauty, my honesty beat me to the punch.

“Yes,” I said. “She’s in the garden.”

CHAPTER TWO

My insurance company impressed me. First, they managed to answer the phone without dumping me in a queue and torturing me with a scratchy looped recording of “Greensleeves,” or whatever it is they play nowadays. Second, the operator, who spoke with an Indian accent but insisted his name was Bruce Jackson, was sympathetic to the plight of the freezing man and directed me to the local branch of Auto Windscreens, who not only had my window in stock but also fitted it while I waited. They even gave me a cup of tea, although I have to say that’s a loose description. Tea should not be served in a plastic cup from a sticky push-button machine, and should never contain coffee whitener. But since I wasn’t offered an alternative, and it was at least warm, I feigned gratitude and drank it.

Repairs completed and schedule abandoned, I stopped off at B&Q for a pack of saw blades and some lye, and somehow also left with a cordless electric sander. Might come in handy. Next I popped into CarpetRight and was able to pick up half a dozen large offcuts, which matched almost perfectly the sample I carry in my glovebox. You can never have too much carpet, believe me.

Hypnotized by the siren call of beef on the breeze, I then drove over to the adjacent McDonald’s where a pretty blonde girl with four gold stars but no name provided me with what she claimed was a cheeseburger, but which upon closer inspection revealed itself to be a cheap imitation of one. Eating it was only marginally more fulfilling than getting stuck in the pitifully narrow drive-thru lane. This was a disappointment, since Miss Gold Stars looked as though she had the potential to make great burgers.

The snow had returned by the time I was back on the road. It came down in a dense flurry, blanketing the ground in minutes and forming a bright, focus-bothering tunnel as I drove.

The road through the forest was unusually quiet, even accounting for the weather; I was making my own tracks and hadn’t passed another vehicle since leaving town. At times like this, unlikely as it seems, it’s perfectly possible to feel at one with nature from inside a heated van.

Two miles after the trees moved in to hug the road, I pulled onto the unmade Forestry Commission trail that follows the main railway line. It’s used in fair weather by dog walkers and cyclists and is inaccessible to motor vehicles, thanks to a steel pole secured to its trestles by a chain and padlock. Fortunately, I have a key.

I locked the gate behind me and, swallowing my regret at disturbing the virgin snow, guided the van along the rutted track for the half mile that would take me out of sight of the main road.

This is what winters were like when I was a child. The snow shin-deep on the ground. Soft, delicate flakes falling around me in their thousands, settling in my hair and gently tickling my face. The air so crisp and still as to dull the cold. Breath rising in front of my eyes, floating up toward a pure, white sky. The soft crunching underfoot with each deliberate step. The blissful, unbreakable silence.

Back then, winters were long and filled with all kinds of mystery. There were the treacherous road trips with my father to far-flung outposts in rented cars. The old stables along the driveway became an arctic shipwreck; discarded junk on high shelves was pirate treasure. And then there was the birch wood beyond the garden, where the ground stayed dry enough to sit and read under a canopy of blankets, and where the shouts and screams from the house could never reach.

Today, though, I had little time to reflect. I’d parked the van where the track meets a swathe of open heathland cut through the forest. From here the ground slopes away toward the railway line, beyond which is a steep drop into a wooded marsh, which lies alongside the river. Where I was standing, the ground falls sharply into a tree-lined crater, about a hundred yards across; at the bottom is a shallow pond fed by a tributary of the river, which winds its way through the marsh and under the railway. Down here the line is supported by a brick tunnel, built when the railway was laid in the 1840s to allow the passage of boats into what was then a working flint pit. Repeatedly pinned and reinforced over the years in a valiant yet inevitably vain struggle against gravity and decay, it shudders and wails with the passing of every train.

Reaching this place requires care even in ideal conditions. In deep snow, carrying a dead weight, it’s a pain in the arse. I had to make two trips, leaving the heavy rubble sack beneath the bridge and returning for the smaller bags and shovel. This time of year, unfortunately, calls for something of a compromise. There’s plenty of good ground out here, firm enough not to be turned over by the occasional trampling; after all, what’s accessible to me is accessible to you, too. However, in these temperatures it’s impossible to dig a hole in it. Any ground soft enough to dig in the depths of winter will be all but impassable in the summer, and therefore, almost inevitably remote and overgrown and generally no place to be carrying luggage.

The error giving rise to the term “shallow grave” is a classic one made time and again by panicked first-timers. It’s common for them to underestimate the time and effort involved in digging up a forest floor; the net result of this is, generally, a very small hole. In order to adequately cover the body, they are forced to build up a sizeable mound of earth from the surrounding area. Since this looks just like a shallow grave, they will then attempt to disguise it with a layer of bracken and moss. And of course, at the first sign of a stiff breeze, the toes are poking out.

Today, I’d be going five feet deep. This could take all winter.

CHAPTER THREE

In death, my father finally smiled. He was still warm when I left him the first time, his skin still soft, cheeks flushed. The blood pooled in the sawdust under his neck, tiny woodchips floating, dancing with one another, drawn together into little snowflake patterns that mimicked the ones still melting into my coat.

I knelt over him, searching his eyes for a flicker of life. The first and only time this strong, proud man would look up at me—his last chance to look at me at all—and yet still unable to truly look at me.

In those few moments, I saw the full range of his emotions pass across his face. The pain of betrayal. The regret of self-inflicted failure. Perplexity at the fascinations of a small boy. Frustration at the demands for attention. Disappointment, anger and loathing. Fear.

After breakfast, I returned and sat beside him, shivering for hours on end, watching the blood congeal and his face wax over. Around midday, the snow on the roof became top-heavy and slid to the ground, startling me. Every now and then a curious vulpine nose snuffled along the gap beneath the door. Otherwise, I had only the silence and the cold for company.

By nightfall he was cool to the touch, his fingers curled into rigid claws, and my hunger got the better of me.

I stumbled back through the garden to the warmth of the house, praying all the way that I’d find my dinner in the oven, my mother there to make sure I ate my vegetables before she tucked me into bed with the promise that tomorrow, everything would be just fine. But I’d seen the look in her eyes when she’d kissed me goodbye that morning, a life and sparkle that I’d never seen there before. Deep down, as I’d watched her grab her bags and sail out of the house, leaving me alone with my porridge, I’d known this exit was different from all the others. This one felt final.

I did the only thing I knew how. I gorged myself on shoo-fly pie and waited for someone to find me. Funny thing is, they never really did.

* * *

Preheat the oven to 260 degrees centigrade.

Juice six oranges; zest two of the rinds and roughly chop the rest. Take two medium-size fillets from the bird of your choosing and make an incision in each. Insert equal measures of the chopped rind and place the whole ensemble in a baking tray with half an inch of water. Bake in the oven until the skin is golden brown and lightly crisped, then turn it down to 150. It’s going to take about an hour.

While that’s cooking, take your zest and the freshly squeezed juice and pop them in a pan along with two-thirds of a cup of sugar. Place the mixture over a medium-to-high heat and reduce it until you’re left with about a quarter of the volume. Throw in a tablespoon of bitters, and set the pan aside.

Boil two cups of chicken stock in a separate pan, then add the orange mixture and simmer it for ten more minutes.

When the meat is done, drain the fat from the baking tray and place the tray on the stove. Pour a cup of Grand Marnier into the tray and cook off the alcohol. Make sure you’ve got a wooden spoon to hand as you will need to scrape the bottom of the tray almost continuously. Next, pour a cup of the orange sauce you made earlier into the tray and cook it for a minute or so.

Finally, remove the orange rinds from the steaks and combine the orange sauce with the remaining juices from the baking tray. Serve with a simple accompaniment of new potatoes and runner beans, et voilà. Sarà l’orange.

I built my garage large enough to comfortably accommodate a full-size van and three cars. An automatic climate-control system maintains a constant temperature of sixty degrees Fahrenheit and minimizes humidity. Twin reinforced canopy doors are operated by remote control, which utilizes a double rolling-code system to ensure maximum peace of mind. I have three transmitters; I keep one on my keychain, and the spares are in a locked box in one of the kitchen cupboards, along with a collection of souvenir door keys amassed over time. The key to the box is on my keychain. Note to self.

The stairs leading down to the basement are accessed via a cupboard, or more specifically the false back thereof, which is lined with lipped shelves containing half-empty paint cans and other objects disinclined to topple when disturbed, and which opens at the flick of a concealed catch into the void between the outer and false inner walls to the rear of the garage. The steps are covered with a heavy-duty nylon cut-pile carpet, mulberry in color with a crisp multipoint stipple-effect pattern, perfect for camouflaging a vast range of dark stains. It’s certificated to all European flammability and antistatic standards for office applications, and is Scotchgard-protected to prevent ingraining. There isn’t an awful lot you can’t drag across a carpet like that.